Facility Assessment, Fire Station Location and Staffing Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Fire Services Study

RegionalRegional FireFire ServicesServices StudyStudy CitiesCities of:of: ClaytonClayton MaplewoodMaplewood OlivetteOlivette RichmondRichmond HeightsHeights UniversityUniversity CityCity NovemberNovember 20092009 Regional Fire Services Study Cities of: Clayton Maplewood Olivette Richmond Heights University City Prepared by Phil Kouwe Kent Greene Martin Goughnour John Best Robert McNally Emergency Services Consulting International 25200 SW Parkway Ave. Suite 3 Wilsonville, Oregon 97070 800-757-3724 www.ESCI.us November 2009 Regional Fire Services Study Clayton, Maplewood, Olivette, Richmond Heights, University City Table of Contents Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................ v Acknowledgements...................................................................................................................... ix Executive Summary ......................................................................................................................1 Report Conventions ......................................................................................................................9 Emergency Services Survey ......................................................................................................9 RECOMMENDATIONS...................................................................................................................................9 Section 1: Emergency Services Agency Evaluations .................................................................11 -

Engine Riding Positions Officer Heo Nozzle Ff

MILWAUKEE FIRE DEPARTMENT Operational Guidelines Approved by: Chief Mark Rohlfing 2012 FORWARD The purpose of these operational guidelines is to make clear expectations for company performance, safety, and efficiency, eliminating the potential for confusion and duplication of effort at the emergency scene. It is understood that extraordinary situations may dictate a deviation from these guidelines. Deviation can only be authorized by the officer/acting officer of an apparatus or the incident commander. Any deviation must be communicated over the incident talk group. The following guidelines are meant to clarify best operational practices for the MFD. They are not intended to be all-inclusive and are designed to be updated as necessary. They are guidelines for you to use. However, there will be no compromise on issues of safety, chain of command, correct gear usage, or turnout times (per NFPA 1710). These operating guidelines will outline tool and task responsibilities for the specific riding positions on responding units. While the title of each riding position and the assignments that follow may not always seem to be a perfect pairing, the tactical advantage of knowing where each member is supposed to be operating at a given assignment will provide for increased accountability and increased effectiveness while performing our response duties. Within the guidelines, you will see run-type specific (and in some cases, arrival order specific) tool and task assignments. On those responses listing a ‘T (or R)’ as the response unit, the Company will be uniformly listed as ‘Truck’ for continuity. The riding positions are as follows: ENGINE RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO NOZZLE FF BACKUP FF TRUCK RIDING POSITIONS OFFICER HEO VENT FF FORCE FF SAFETY If you see something that you believe impacts our safety, it is your duty to report it to your superior Officer immediately. -

TFT Guide to Nozzles

CONTENTS 10 COMMON QUESTIONS ABOUT AUTOMATIC EVOLUTION OF FIRE STREAMS.......................................................2 NOZZLES EVOLUTION OF COMBINATION NOZZLES......................................3 1) How is an automatic nozzle different from a regular (conventional) UNDERSTANDING FIRE NOZZLE DESIGN ......................................5 nozzle? LIMITATIONS OF CONVENTIONAL NOZZLES.................................6 2) How does an automatic nozzle work? AUTOMATIC NOZZLES INVENTED................................................ 10 3) What pressure do we pump to automatic nozzles? BENEFITS OF AUTOMATIC NOZZLES .......................................... 13 4) How do I know how much water I am flowing? SLIDE VALVE vs. BALL VALVE ..................................................... 16 5) What is the flow from each "Click Stop" on the nozzle? TRAINING CONSIDERATIONS WITH AUTOMATICS .................... 18 6) Can I use automatics with foam and foam eductors? USING LARGER SIZE ATTACK LINES .......................................... 21 7) Why don't all automatic nozzles have spinning teeth? 8) What type of nozzle is best for “Nozzleman Flow Control?” BOOSTER TANK OPERATIONS..................................................... 22 SHAPING THE FIRE STREAM PATTERN ...................................... 23 9) Is it true that the stream from a "SOLID" bore nozzle hits harder and goes farther than the "Hollow”' stream from a fog nozzle? SMOOTH BORE vs. FOG TIP .......................................................... 24 FLUSHING DEBRIS......................................................................... -

Engine Company Operations

Fire and Rescue Departments of Northern Virginia Firefighting and Emergency Operations Volume I - General Firefighting Procedures Book 2 Issued November 2003 Engine Company Operations Developed through a cooperative effort between the Fire and Rescue Departments of Arlington County City of Alexandria City of Fairfax Fairfax County Fort Belvoir Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority Committee members who developed this book Chair Deputy Chief Jeffrey B. Coffman, Fairfax County Battalion Chief John J. Caussin, Fairfax County Battalion Chief John M. Gleske, Fairfax County Captain David G. Lange, Fairfax County Battalion Chief Jeffery M. Liebold, Arlington County Captain Mark W. Dalton, City of Alexandria Captain Joel A. Hendelman, City of Fairfax Captain Thomas J. Wealand, Fairfax County Captain Chris Larson, MWAA Captain Michael A. Deli, Fairfax County Captain Floyd L. Ellmore, Fairfax County Captain Larry E. Jenkins, Fairfax County TABLE OF CONTENTS ENGINE COMPANY OPERATIONS 1. Introduction 1.1 Background 1.2 Purposes 2. Planning 3. Responding 3.1 Typical Response and Arrival Considerations 3.2 Single Engine Response 3.3 Multi-Engine Response 3.3.2 First-Due Engine 3.3.3 Second-Due Engine 3.34 Third-Due Engine 3.3.5 Fourth-Due Engine 3.3.6 First-Due Engine, Second Alarm 3.4 Monitoring Radio Traffic 3.5 Safety 3.6 Altered Response Routes 4. Fire Scene Operations 4.1 Objectives 4.2 Strategy 4.3 Tactics 4.4 Size Up 4.4.2 Strategic factors that must be considered during size-up include: 4.5 Rescue 4.6 Locating the fire 4.7 Confinement 4.8 Extinguishment 4.9 Determining Fire Flow 4.10 Rules for Stream Position 4.11.1 Engine Officer 4.13.2 Guidelines to Assist with Smooth Line Advancement Table of Contents Engine Company Operations Page 2 5. -

FMD Fire Investigators Announce Retirement Fire Prevention Week

October 2003 Vol 5, Issue 10 Fire Prevention Week - October 5-11, 2003 NFPA has announced the week of October 5-11 as Fire Prevention Week (FPW) 2003. The State Fire Marshal’s Office is joining forces with fire departments, schools, and safety groups across North Special Interest: America to reinforce a simple, but lifesaving message during Fire Prevention Week: “When Fire Stirkes: Get Out! Stay Out!” Public Safety Campaign to At least 80% of all fire deaths typically take place in the home, so this Reduce Fire Deaths of Babies and Toddlers... .....3 year the focus is on home fire safety. The fire service, in planning FPW activities, should relay three important messages to their community: Homes should have working smoke alarms on every Zippotricks.com ............... 3 level; plan and practice a home fire drill; and, if fire strikes, get out and Non-Reporting Fire stay out, until the fire department says it is safe to go back inside. Departments (NFIRS) ..... 5 For more information about Fire Prevention Week and activities your department can perform, log on to the official web site MFFTC Instructor Alert ..... 9 www.firepreventionweek.org. Breakfast with the Detroit Fire Department ........... 11 FMD Fire Investigators Announce Retirement D/Lt. Larry Lewis and Spl/Sgt. tration and supervision of five James Curran have announced investigators. He has been a their retirement from the Michigan member of various fire service Inside this Issue: State Police effective August 30, organizations involved in fire 2003, after 25 years of service. safety, education and arson August Fire Deaths ........... 2 D/Lt. -

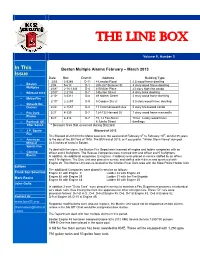

The Line Box

The Line Box Volume 9, Number 5 In This Boston Multiple Alarms February – March 2013 Issue Date Box District Address Building Type 2/03 2-5385 D-11 4 Langley Road 2.5 wood frame dwelling Boston 2/04 5-613 D-1 265-267 Summer St. 3 story wood frame dwelling Multiples 2/08* 2-16-1344 D-4 8 Whittier Place 23 story high-rise condo Blizzard 2013 2/09* 2-2138 D-7 5 Burton Street 4 story brick dwelling 2/10* 3-3311 D-8 49 Mather Street 3 story wood frame dwelling Metro-Fire 2/10* 2-2297 D-9 5 Cobden Street 3.5 story wood frame dwelling Outside the District 2/20 2-1537 D-4 17 Commonwealth Ave 5 story brick/wood condo Fire Duty 3/27 4-339 D-7 124-132 Harvard St 1 story wood frame mercantile Photos 3/27 6-314 D-7 10, 12 Fox Street Three 3 story wood frame Portland, OR 8 Julette Street dwellings Tiller Squad * Denotes fires that occurred during Blizzard J.P. Squire Blizzard of 2013 Fire The Blizzard of 2013 hit the Metro area over the weekend of February 8th to February 10th, almost 35 years American to the day of the Blizzard of 1978. The Blizzard of 2013, or if you prefer, “Winter Storm Nemo” dumped Mineral 24.6 inches of snow in Boston. Spirits Fire To deal with the storm, the Boston Fire Department manned all engine and ladder companies with an Coming officer and 4 firefighters. The Rescue Companies were manned with and officer and 5 firefighters. -

Fire Fighter FACE Report No. F2002-49, Volunteer

F2002 Death in the 49 Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program line of duty... A Summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation November 21, 2003 Volunteer Lieutenant Dies Following Structure Collapse at Residential House Fire - Pennsylvania SUMMARY On November 1, 2002, a 36-year-old male • ensure that Incident Command (IC) volunteer Lieutenant (the victim) died after being continually evaluates the risk versus gain crushed by an exterior wall that collapsed during a when deciding an offensive or defensive fire three-alarm residential structure fire. The victim was attack operating a handline near the southwest corner of the fire building where there was an overhanging • ensure that a collapse zone is established, porch. As the fire progressed, the porch collapsed clearly marked, and monitored at structure onto the victim, trapping him under the debris. Efforts fires where buildings have been identified at were being made by nearby fire fighters to free him risk of collapsing when the entire exterior wall of the structure collapsed outward and he was crushed. The victim was • establish and implement written standard removed from the debris within ten minutes, but operating procedures (SOPs) regarding attempts to revive him were unsuccessful and he was emergency operations on the fireground pronounced dead at the scene. • develop and coordinate pre-incident planning NIOSH investigators concluded that, to minimize the protocols throughout mutual aid departments risk of similar occurrences, fire departments should: • implement joint training on response protocols throughout mutual aid departments • ensure that an Incident Safety Officer, independent from the Incident Commander, is appointed and on-scene early in the fireground operation The Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program is conducted by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). -

Sunrise Fire Rescue Operations and Policy Manual

UPDATED ON 6/21/2016 OPERATIONS AND POLICIES MANUAL Sunrise Fire Rescue Operations & Policies Manual Index June 21, 2016 SECTION 1 ORGANIZATION 100.00 Mission Statement August 4, 2003 100.01 Organizational Structure October 1, 2013 100.02 Operations & Policies Manual (OPM) February 3, 2014 SECTION 2 HUMAN RESOURCES 200.00 Duties & Responsibilities 200.01 Firefighter/EMT December 23, 2014 200.02 Firefighter/Paramedic December 23, 2014 200.03 Fire Inspector December 23, 2014 200.04 Driver Operator December 23, 2014 200.05 Rescue Lieutenant – Section 1 Shift December 23, 2014 200.05 Rescue Lieutenant – Section 2 Non Shift December 23, 2014 200.06 Fire Captain December 23, 2014 Sect. 1 Fire Captain EMS Shift Supervisor December 23, 2014 Sect. 2 Fire Captain EMS Non Shift December 23, 2014 Sect. 3 Fire Captain Fire Life Safety December 23, 2014 Sect. 4 Fire Captain Plan Review December 23, 2014 Sect. 5 Fire Captain Logistics December 23, 2014 Sect. 6 Fire Captain Special Operations July 28, 2010 Sect. 7 Fire captain Training April 30, 2013 200.07 Fire Marshal April 27, 2011 200.08 Battalion Chief April 30, 2013 Sect. 1 Support Battalion Chief April 30, 2013 Sect 2 Emergency Management Battalion Chief April 30, 2013 200.09 Fire Division Chief April 30, 2013 201.00 Promotional Qualifications 201.01 Entry Level/Firefighter December 23, 2014 201.02 Driver Operator December 23, 2014 201.03 Rescue Lieutenant December 23, 2014 201.04 Fire Captain December 23, 2014 201.06 Battalion Chief December 23, 2014 201.07 Special Operations Team Member April -

Golden Valley Fire District

Golden Valley Fire District Daily Quick Drills Volume 8, Numbers 1-10 The daily quick drill is designed to assist the company officer in delivery of a quick review of a department policy or procedure. Reviews of basic fire- fighting, ems and special response situations should be referenced to appropriate SOG’s. Golden Valley Fire District Daily Quick Drills Volume 16 , Number 1 Severe Weather Review department policies and procedures for actions to be taken in the event of severe weather and storms. What should both on-duty and off-duty personnel do? Golden Valley Fire District Daily Quick Drills Volume 8, Number 2 Safety—Wires at Fires Be aware of downed or any wires at a fire scene. -How can wire hazards be identified on the fireground? -Who was in danger at this incident? -What should be done to secure and mark the wires once it is re- moved from the firefighter? (How should it be removed) Golden Valley Fire District Daily Quick Drills Volume 8, Number 3 Brush Fires Review equipment and procedures for Brush Fires. -What is the standard response -What brush fire equipment is available -What resources are available outside of your depart- ment for brush fire operations What tactic is used for brush fire operations that is different from typical structure fire operations? Golden Valley Fire District Daily Quick Drills Volume 8, Number 4 EMS—Rule of 9’s Review EMS Protocols for Burn Injuries Golden Valley Fire District Daily Quick Drills Volume 8, Number 5 Dumpster Fires What levels of protective clothing are appropriate for dumpster fires? What hazards could be present inside the dumpster? Where should apparatus be positioned for fire attack at a dumpster fire? What alternatives to traditional trash line attack on dumpster fires is available? What discharge pressure should the trash line be operated at? What should be done if a dumpster has an exposure to a building? Golden Valley Fire District Daily Quick Drills Volume 8, Number 6 Methods of Forcing a Door Review Essentials on Forcible Entry. -

Fall River County Community Wildfire Protection Plan Working Document

Fall River County Community Wildfire Protection Plan Working document: 6/24/2009 Acknowledgements Any community planning process requires a great deal of work and commitment from a wide variety of people. This plan was initiated by the Fall River Emergency Management in Hot Springs with financial assistance provided by the State of South Dakota. The majority of the work on this plan was done in collaboration with the dedicated volunteer fire fighters. This plan was created for the benefit of the volunteer fire fighters and the citizens of Fall River County. Prepared For: Fall River County Emergency Management Frank Maynard 906 N River Street Hot Springs, SD 57747 Voice: (605) 745-7562 Mobile: (605) 890-7245 Email: [email protected] Prepared By: Black Hills Land Analysis Rob Mattox 12007 Coyote Ridge Road Deadwood, SD 57732 605-578-1556 [email protected] www.mattox.biz Table of Contents Introduction ………….........................……………………………………....…...5 The Healthy Forest Restoration Act ………........................………..………..6 Community Discussion …………………….......................………….............6 Fire Protection …………………………..........................……………...…….......8 Fire History ………………………..........................………………..………...…...8 Values ……………………………............................………………….......…….….9 Structural Hazard Assessment .......................................................................11 Historical Sites .......................................................................................12 Hazards ……………………........................……………………...….................12 -

Syllabus for Fire Service Hydraulics

DEPARTMENT OF FINANCIAL SERVICES Division of State Fire Marshal Bureau of Fire Standards and Training Title: Syllabus for Fire Service Hydraulics Revision: October 2019 Section I - Course Information Course Title: Fire Service Hydraulics Course Number(s): BFST/FFP/ATP1301 Class Days/Time: If being taught at the Florida State Fire College Campus 11655 NW Gainesville Road, Ocala, FL 34482 Bldg. C – Classrooms – Monday - Friday 8 a.m.- 5 p.m. Additional coursework outside the classroom totaling five (5) hours of work may be assigned. Section II - Points of Contact Training Supervisor: Name: Frank Ennist Email: [email protected] Work Phone: 352-369-2838 Bldg. C Room 158 Program Manager: Name: Email: Work Phone: Bldg. C Room 158 Section III – Course Description This course covers the relationship between flow, pressure, and mathematical hydraulic formulas. The course includes pump theory, pump rating, and pressure and vacuum gauges. Section IV - Course Materials, Grading, and Attendance Recommended Book: Pumping and Aerial Apparatus Driver/Operator Handbook (3rd ed.); IFSTA Publishing (2015) ISBN: 978-087039571-1 Prerequisite(s): None THE BUREAU OF FIRE STANDARDS and TRAINING AT The Florida State Fire College 11655 NW Gainesville Road • Ocala Florida • 34482-1486 352.369.2800 • www.floridastatefirecollege.org Page 1 of 5 Contact Hours: This class has 45 contact hours. Continuing Educations Units (CEU’s): 45 hours towards Fire Safety Inspector, Instructor I, II, III renewal Pre-Course Assignment: None Required Materials: Paper, pens, USB portable storage device (thumb drive) Grading: Students must achieve a minimum cumulative score of 70% to pass this course. Course grades are determined from assignments and activities including, homework, projects, quizzes, exams, and presentations. -

Fireterminology.Pdf

Abandonment: Abandonment occurs when an emergency responder begins treatment of a patient and the leaves the patient or discontinues treatment prior to arrival of an equally or higher trained responder. Abrasion: A scrape or brush of the skin usually making it reddish in color and resulting in minor capillary bleeding. Absolute Pressure: The measurement of pressure, including atmospheric pressure. Measured in pound per square inch absolute. Absorption: A defensive method of controlling a spill by applying a material that absorbs the spilled material. Accelerant: Flammable fuel (often liquid) used by some arsonists to increase size or intensity of fire. Accelerator: A device to speed the operation of the dry sprinkler valve by detecting the decrease in air pressure resulting in acceleration of water flow to sprinkler heads. Accountability: The process of emergency responders (fire, police, emergency medical, etc...) checking in as being on-scene during an incident to an incident commander or accountability officer. Through the accountability system, each person is tracked throughout the incident until released from the scene by the incident commander or accountability officer. This is becoming a standard in the emergency services arena primarily for the safety of emergency personnel. Adapter: A device that adapts or changes one type of hose thread, type or size to another. It allows for connection of hoses and pipes of incompatible diameter, thread, or gender. May contain combinations, such as a double-female reducer. Adapters between multiple hoses are called wye, Siamese, or distributor. Administrative Warrant: An order issued by a magistrate that grants authority for fire personnel to enter private property for the purpose of conducting a fire prevention inspection or similar purpose.