Ugandan Literature: the Questions of Identity, Voice and Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Translation of African Literature: a German Model? Jean-Pierre Richard

Translation of African Literature: A German Model? Jean-Pierre Richard To cite this version: Jean-Pierre Richard. Translation of African Literature: A German Model?. IFAS Working Paper Series / Les Cahiers de l’ IFAS, 2005, 6, p. 39-44. hal-00797996 HAL Id: hal-00797996 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00797996 Submitted on 7 Mar 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Les Nouveaux Cahiers de l´IFAS IFAS Working Paper Series Translation - Transnation 1994 – 2004 Dix ans d´echanges littéraires entre l´Afrique du Sud et la France Ten years of literary exchange between South Africa and France Numéro special Rassemblé et dirigé par Jean-Pierre RICHARD, Université Paris 7, en collaboration avec Denise GODWIN, rédactrice de l´AFSSA Special issue collated and edited by Jean-Pierre RICHARD, University of Paris 7, in collaboration with AFSSA editor, Denise GODWIN N0 6, August 2005 Translation – Transnation 1994-2004 Ten years of literary exchange between South Africa and France Dix ans d’échanges littéraires entre l’Afrique du Sud et la France To Sello Duiker and Phaswane Mpe Contents – Sommaire Preface – Préface The authors – Les auteurs About translation – Etudes L’autre source : le rôle des traducteurs dans le transfert en français de la littérature sud-africaine par J.-P. -

Your Voice Assistant Is Mine: How to Abuse Speakers to Steal Information and Control Your Phone ∗ †

Your Voice Assistant is Mine: How to Abuse Speakers to Steal Information and Control Your Phone ∗ y Wenrui Diao, Xiangyu Liu, Zhe Zhou, and Kehuan Zhang Department of Information Engineering The Chinese University of Hong Kong {dw013, lx012, zz113, khzhang}@ie.cuhk.edu.hk ABSTRACT General Terms Previous research about sensor based attacks on Android platform Security focused mainly on accessing or controlling over sensitive compo- nents, such as camera, microphone and GPS. These approaches Keywords obtain data from sensors directly and need corresponding sensor invoking permissions. Android Security; Speaker; Voice Assistant; Permission Bypass- This paper presents a novel approach (GVS-Attack) to launch ing; Zero Permission Attack permission bypassing attacks from a zero-permission Android application (VoicEmployer) through the phone speaker. The idea of 1. INTRODUCTION GVS-Attack is to utilize an Android system built-in voice assistant In recent years, smartphones are becoming more and more popu- module – Google Voice Search. With Android Intent mechanism, lar, among which Android OS pushed past 80% market share [32]. VoicEmployer can bring Google Voice Search to foreground, and One attraction of smartphones is that users can install applications then plays prepared audio files (like “call number 1234 5678”) in (apps for short) as their wishes conveniently. But this convenience the background. Google Voice Search can recognize this voice also brings serious problems of malicious application, which have command and perform corresponding operations. With ingenious been noticed by both academic and industry fields. According to design, our GVS-Attack can forge SMS/Email, access privacy Kaspersky’s annual security report [34], Android platform attracted information, transmit sensitive data and achieve remote control a whopping 98.05% of known malware in 2013. -

Expert's Views on the Dilemmas of African Writers

EXPERTS’ VIEWS ON THE DILEMMAS OF AFRICAN WRITERS: CONTRIBUTIONS, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS By Sarah Kaddu Abstract African writers have faced the “dilemma syndrome” in the execution of their mission. They have faced not only “bed of roses” but also “the bed of thorns”. On one hand, African writers such as Chinua Achebe have made a fortune from royalties from his African Writers’ Series (AWS) and others such as Wole Soyinka, Ben Okri and Naruddin Farah have depended on prestigious book prizes. On the other hand, some African writers have also, according to Larson (2001), faced various challenges: running bankrupt, political and social persecution, business sabotage, loss of life or escaping catastrophe by “hair breadth”. Nevertheless, the African writers have persisted with either success or agony. Against this backdrop, this paper examines the experts’ views on the contributions of African writers to the extending of national and international frontiers in publishing as well as the attendant handicaps before proposing strategies for overcoming the challenges encountered. The specific objectives are to establish some of the works published by the African writers; determine the contribution of the works published by African writers to in terms of political, economic, and cultural illumination; examine the challenges encountered in the publishing process of the African writers’ works; and, predict trends in the future of the African writers’ series. The study findings illuminate on the contributions to political, social, gender, cultural re-awakening and documentation, poetry and literature, growth of the book trade and publishing industry/employment in addition to major challenges encountered. The study entailed extensive analysis of literature, interviews with experts on African writings from the Uganda Christian University and Makerere University, and African Writers Trust; focus group discussions with publishers, and a few selected African writers, and a review of the selected pioneering publications of African writers. -

User Guide Guía Del Usuario Del Guía GH68-43542A Printed in USA SMARTPHONE

User Guide User Guide GH68-43542A Printed in USA Guía del Usuario del Guía SMARTPHONE User Manual Please read this manual before operating your device and keep it for future reference. Legal Notices Warning: This product contains chemicals known create source code from the software. No title to or to the State of California to cause cancer and ownership in the Intellectual Property is transferred to reproductive toxicity. For more information, please call you. All applicable rights of the Intellectual Property 1-800-SAMSUNG (726-7864). shall remain with SAMSUNG and its suppliers. Intellectual Property Open Source Software Some software components of this product All Intellectual Property, as defined below, owned by incorporate source code covered under GNU General or which is otherwise the property of Samsung or its Public License (GPL), GNU Lesser General Public respective suppliers relating to the SAMSUNG Phone, License (LGPL), OpenSSL License, BSD License and including but not limited to, accessories, parts, or other open source licenses. To obtain the source code software relating there to (the “Phone System”), is covered under the open source licenses, please visit: proprietary to Samsung and protected under federal http://opensource.samsung.com. laws, state laws, and international treaty provisions. Intellectual Property includes, but is not limited to, inventions (patentable or unpatentable), patents, trade secrets, copyrights, software, computer programs, and Disclaimer of Warranties; related documentation and other works of authorship. -

SAMSUNG GALAXY S6 USER GUIDE Table of Contents

SAMSUNG GALAXY S6 USER GUIDE Table of Contents Basics 55 Camera 71 Gallery 4 Read me first 73 Smart Manager 5 Package contents 75 S Planner 6 Device layout 76 S Health 8 SIM or USIM card 79 S Voice 10 Battery 81 Music 14 Turning the device on and off 82 Video 15 Touchscreen 83 Voice Recorder 18 Home screen 85 My Files 24 Lock screen 86 Memo 25 Notification panel 86 Clock 28 Entering text 88 Calculator 31 Screen capture 89 Google apps 31 Opening apps 32 Multi window 37 Device and data management 41 Connecting to a TV Settings 43 Sharing files with contacts 91 Introduction 44 Emergency mode 91 Wi-Fi 93 Bluetooth 95 Flight mode Applications 95 Mobile hotspot and tethering 96 Data usage 45 Installing or uninstalling apps 97 Mobile networks 46 Phone 97 NFC and payment 49 Contacts 100 More connection settings 51 Messages 102 Sounds and notifications 53 Internet 103 Display 54 Email 103 Motions and gestures 2 Table of Contents 104 Applications 104 Wallpaper 105 Themes 105 Lock screen and security 110 Privacy and safety 113 Easy mode 113 Accessibility 114 Accounts 115 Backup and reset 115 Language and input 116 Battery 116 Storage 117 Date and time 117 User manual 117 About device Appendix 118 Accessibility 133 Troubleshooting 3 Basics Read me first Please read this manual before using the device to ensure safe and proper use. • Descriptions are based on the device’s default settings. • Some content may differ from your device depending on the region, service provider, model specifications, or device’s software. -

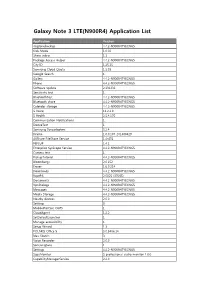

Galaxy Note 3 LTE(N900R4) Application List

Galaxy Note 3 LTE(N900R4) Application List Application Version ringtonebackup 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 Kids Mode 1.0.02 Share video 1.1 Package Access Helper 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 City ID 1.25.15 Samsung Cloud Quota 1.5.03 Google Search 1 Gallery 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 Phone 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 Software update 2.131231 Sensitivity test 1 BluetoothTest 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 Bluetooth share 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 Calendar storage 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 S Voice 11.2.2.0 S Health 2.5.4.170 Communication Notifications 1 DeviceTest 1 Samsung Syncadapters 5.2.4 Drama 1.0.0.107_201400429 AllShare FileShare Service 1.4r476 PEN.UP 1.4.1 Enterprise SysScope Service 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 Camera test 1 PickupTutorial 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 Bloomberg+ 2.0.152 Eraser 1.6.0.214 Downloads 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 RootPA 2.0025 (37085) Documents 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 VpnDialogs 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 Messages 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 Media Storage 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 Nearby devices 2.0.0 Settings 3 MobilePrintSvc_CUPS 1 CloudAgent 1.2.2 SetDefaultLauncher 1 Manage accessibility 1 Setup Wizard 1.3 POLARIS Office 5 5.0.3406.14 Idea Sketch 3 Voice Recorder 2.0.0 SamsungSans 1 Settings 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 SapaMonitor S professional audio monitor 1.0.0 CapabilityManagerService 2.4.0 S Note 3.1.0 Samsung Link 1.8.1904 Samsung WatchON Video 14062601.1.21.78 Street View 1.8.1.2 Alarm 1 PageBuddyNotiSvc 1 Favorite Contacts 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 Google Search 3.4.16.1149292.arm KNOX 2.0.0 Exchange services 4.2 GestureService 1 Weather 140211.01 Samsung Print Service Plugin 1.4.140410 Tasks provider 4.4.2-N900R4TYECNG5 -

Samsung Galaxy A8

SM-A530F SM-A530F/DS SM-A730F SM-A730F/DS User Manual English (LTN). 12/2017. Rev.1.0 www.samsung.com Table of Contents Basics Apps and features 4 Read me first 52 Installing or uninstalling apps 6 Device overheating situations and 54 Bixby solutions 70 Phone 10 Device layout and functions 75 Contacts 14 Battery 79 Messages 17 SIM or USIM card (nano-SIM card) 82 Internet 23 Memory card (microSD card) 84 Email 27 Turning the device on and off 85 Camera 28 Initial setup 100 Gallery 30 Samsung account 106 Always On Display 31 Transferring data from your previous 108 Multi window device 113 Samsung Pay 35 Understanding the screen 117 Samsung Members 47 Notification panel 118 Samsung Notes 49 Entering text 119 Calendar 120 Samsung Health 124 S Voice 126 Voice Recorder 127 My Files 128 Clock 129 Calculator 130 Radio 131 Game Launcher 134 Dual Messenger 135 Samsung Connect 139 Sharing content 140 Google apps 2 Table of Contents Settings 182 Google 182 Accessibility 142 Introduction 183 General management 142 Connections 184 Software update 143 Wi-Fi 185 User manual 146 Bluetooth 185 About phone 148 Data saver 148 NFC and payment 151 Mobile Hotspot and Tethering 152 SIM card manager (dual SIM Appendix models) 186 Troubleshooting 152 More connection settings 155 Sounds and vibration 156 Notifications 157 Display 158 Blue light filter 158 Changing the screen mode or adjusting the display color 160 Screensaver 160 Wallpapers and themes 161 Advanced features 163 Device maintenance 165 Apps 166 Lock screen and security 167 Face recognition 169 Fingerprint recognition 173 Smart Lock 173 Samsung Pass 176 Secure Folder 180 Cloud and accounts 181 Backup and restore 3 Basics Read me first Please read this manual before using the device to ensure safe and proper use. -

Claim No. Anne Giwa-Amu Claimant

/,., . Claim No. Anne Giwa-Amu Claimant -and- Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie 1St Defendant ~Iarper Collins Publishers Ltd 2°~ Defendant ~,I..Y „~ S sS/~ ,q ~P+ '~a¢raa Pt~RTICULARS OF CLAIM m y e ~~NTY G~~ 1)The Claimant is a qualified Solicitor and obtained her LL.B degree from the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE). The Claimant lived in Nigeria from 1961 — 1974. She is a UK resident and the author of the literary novel `SADE'/'SADE United We Stand'. 2) In 1993, the Claimant started writing the literary novel now entitled SADE which was based on her own knowledge and experiences in Nigeria. Over many years, the Claimant had carried out extensive research, visited the Red Cross Centre at Guilford and interviewed a number of people, including Dr Patrick Ediomi Davis (Paddy Davies) who had worked for the Biafran Propaganda Secretariat. Paddy Davies obtained a degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) on the use of propaganda in civil war focusing on the Biafran experience. The Claimant collated and interpreted material and compiled the sequence of events in SADE exerting a substantial amount of skill, labour and judgement. 3)Between 1994-1995, the Claimant sent a copy of her manuscript to the 2"d Defendant along with other publishing houses. Although Heinemann UK accepted Sade for 1 ~... publication under the African Writers' Series they failed to publish. Chinua Achebe was one of the founding editors of the African Writers' Series which had been established to promote black African literature. The novel was also accepted for publication by Longman UK who also failed to publish following to a policy decision not to publish Nigerian literature due to a lack of market. -

Prizing African Literature: Awards and Cultural Value

Prizing African Literature: Awards and Cultural Value Doseline Wanjiru Kiguru Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, Stellenbosch University Supervisors: Dr. Daniel Roux and Dr. Mathilda Slabbert Department of English Studies Stellenbosch University March 2016 i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained herein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2016 Signature…………….………….. Copyright © 2016 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Dedication To Dr. Mutuma Ruteere iii Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract This study investigates the centrality of international literary awards in African literary production with an emphasis on the Caine Prize for African Writing (CP) and the Commonwealth Short Story Prize (CWSSP). It acknowledges that the production of cultural value in any kind of setting is not always just a social process, but it is also always politicised and leaning towards the prevailing social power. The prize-winning short stories are highly influenced or dependent on the material conditions of the stories’ production and consumption. The content is shaped by the prize, its requirements, rules, and regulations as well as the politics associated with the specific prize. As James English (2005) asserts, “[t]here is no evading the social and political freight of a global award at a time when global markets determine more and more the fate of local symbolic economies” (298). -

List of Participants to the Third Session of the World Urban Forum

HSP HSP/WUF/3/INF/9 Distr.: General 23 June 2006 English only Third session Vancouver, 19-23 June 2006 LIST OF PARTICIPANTS TO THE THIRD SESSION OF THE WORLD URBAN FORUM 1 1. GOVERNMENT Afghanistan Mr. Abdul AHAD Dr. Quiamudin JALAL ZADAH H.E. Mohammad Yousuf PASHTUN Project Manager Program Manager Minister of Urban Development Ministry of Urban Development Angikar Bangladesh Foundation AFGHANISTAN Kabul, AFGHANISTAN Dhaka, AFGHANISTAN Eng. Said Osman SADAT Mr. Abdul Malek SEDIQI Mr. Mohammad Naiem STANAZAI Project Officer AFGHANISTAN AFGHANISTAN Ministry of Urban Development Kabul, AFGHANISTAN Mohammad Musa ZMARAY USMAN Mayor AFGHANISTAN Albania Mrs. Doris ANDONI Director Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Telecommunication Tirana, ALBANIA Angola Sr. Antonio GAMEIRO Diekumpuna JOSE Lic. Adérito MOHAMED Adviser of Minister Minister Adviser of Minister Government of Angola ANGOLA Government of Angola Luanda, ANGOLA Luanda, ANGOLA Mr. Eliseu NUNULO Mr. Francisco PEDRO Mr. Adriano SILVA First Secretary ANGOLA ANGOLA Angolan Embassy Ottawa, ANGOLA Mr. Manuel ZANGUI National Director Angola Government Luanda, ANGOLA Antigua and Barbuda Hon. Hilson Nathaniel BAPTISTE Minister Ministry of Housing, Culture & Social Transformation St. John`s, ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA 1 Argentina Gustavo AINCHIL Mr. Luis Alberto BONTEMPO Gustavo Eduardo DURAN BORELLI ARGENTINA Under-secretary of Housing and Urban Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Development Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Ms. Lydia Mabel MARTINEZ DE JIMENEZ Prof. Eduardo PASSALACQUA Ms. Natalia Jimena SAA Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Session Leader at Networking Event in Profesional De La Dirección Nacional De Vancouver Políticas Habitacionales Independent Consultant on Local Ministerio De Planificación Federal, Governance Hired by Idrc Inversión Pública Y Servicios Buenos Aires, ARGENTINA Ciudad Debuenosaires, ARGENTINA Mrs. -

Samsung Galaxy Note 5 N920R6 User Manual

SMART PHONE User Manual Please read this manual before operating your device and keep it for future reference. Legal Notices Warning: This product contains chemicals known to Disclaimer of Warranties; the State of California to cause cancer, birth defects, or other reproductive harm. For more information, Exclusion of Liability please call 1-800-SAMSUNG (726-7864). EXCEPT AS SET FORTH IN THE EXPRESS WARRANTY CONTAINED ON THE WARRANTY PAGE ENCLOSED WITH THE PRODUCT, THE Intellectual Property PURCHASER TAKES THE PRODUCT “AS IS”, AND All Intellectual Property, as defined below, owned SAMSUNG MAKES NO EXPRESS OR IMPLIED by or which is otherwise the property of Samsung WARRANTY OF ANY KIND WHATSOEVER WITH or its respective suppliers relating to the SAMSUNG RESPECT TO THE PRODUCT, INCLUDING BUT Phone, including but not limited to, accessories, NOT LIMITED TO THE MERCHANTABILITY OF THE parts, or software relating there to (the “Phone PRODUCT OR ITS FITNESS FOR ANY PARTICULAR System”), is proprietary to Samsung and protected PURPOSE OR USE; THE DESIGN, CONDITION OR under federal laws, state laws, and international QUALITY OF THE PRODUCT; THE PERFORMANCE treaty provisions. Intellectual Property includes, OF THE PRODUCT; THE WORKMANSHIP OF THE but is not limited to, inventions (patentable or PRODUCT OR THE COMPONENTS CONTAINED unpatentable), patents, trade secrets, copyrights, THEREIN; OR COMPLIANCE OF THE PRODUCT software, computer programs, and related WITH THE REQUIREMENTS OF ANY LAW, RULE, documentation and other works of authorship. You SPECIFICATION OR CONTRACT PERTAINING may not infringe or otherwise violate the rights THERETO. NOTHING CONTAINED IN THE secured by the Intellectual Property. Moreover, INSTRUCTION MANUAL SHALL BE CONSTRUED you agree that you will not (and will not attempt TO CREATE AN EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTY to) modify, prepare derivative works of, reverse OF ANY KIND WHATSOEVER WITH RESPECT TO engineer, decompile, disassemble, or otherwise THE PRODUCT. -

SCSL Press Clippings

SPECIAL COURT FOR SIERRA LEONE OUTREACH AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS OFFICE Historic postcard. PRESS CLIPPINGS Enclosed are clippings of local and international press on the Special Court and related issues obtained by the Outreach and Public Affairs Office as at: Wednesday, 7 July 2010 Press clips are produced Monday through Friday. Any omission, comment or suggestion, please contact Martin Royston-Wright Ext 7217 2 Local News Ex-Rebel Denies Giving Charles Taylor Diamond / The Spectator Page 3 Issa Sesay Defends Charles Taylor / The Torchlight Page 4 Former Rebel Leader Continues to Distance Charles Taylor…/ CharlesTaylorTrial.org Pages 5-6 Naomi Campbell Faces Jail Time if She Ignores Subpoena / MmegiOnline Page 7 UNMIL Public Information Office Media Summary / UNMIL Pages 8-13 Trial Hears Lubanga Told Child Soldier To Get Women, Vehicles and Cows / ICC Pages 14-15 Relatives Seek Genocide Charges Against Srebrenica Peacekeepers / Radio Netherlands Worldwide Page 16 3 The Spectator Wednesday, 7 July 2010 4 The Torchlight Wednesday, 7 July 2010 5 CharlesTaylorTrial.org (The Hague) Tuesday, 6 July 2010 Sierra Leone: Former Rebel Leader Continues to Distance Charles Taylor From Sierra Leonean Rebel Crimes Alpha Sesay In his second day of testimony, a former Sierra Leonean rebel leader continued to distance Charles Taylor from wrongdoing during the country's bloody 11-year conflict, pointing instead to the United Nations and other Liberian rebel groups who did more to further the rebel cause through weapons supplies and other assistance than the former Liberian president ever did. He also told the court that Mr. Taylor was not responsible for an arms drop-off that is at the center of allegations related to supermodel Naomi Campbell.