Top Chef and Taste

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chopped All-Stars

Press Contact: Lauren Sklar Phone: 646-336-6745; E-mail: [email protected] *High-res images, show footage, and interviews available upon request. CHOPPED ALL-STARS Season Two Judge/Host Bios Ted Allen Emmy Award winner Ted Allen is the host of Chopped, Food Network’s hit primetime culinary competition show, and the author of the upcoming cookbook “In My Kitchen: 100 Recipes and Discoveries for Passionate Cooks” debuting in May, 2012, and an earlier book, "The Food You Want to Eat: 100 Smart, Simple Recipes," both from Clarkson- Potter. Ted also has been a contributing writer to Esquire magazine since 1996. Previously, he was the food and wine specialist on the groundbreaking Bravo series Queer Eye, a judge on Food Network's Iron Chef America, and a judge on Bravo’s Top Chef. He lives in Brooklyn with his longtime partner, interior designer Barry Rice. Anne Burrell Anne Burrell has always stood out in the restaurant business for her remarkable culinary talent, bold and creative dishes, and her trademark spiky blond hair. After training at New York’s Culinary Institute of America and Italy’s Culinary Institute for Foreigners, she gained hands-on experience at notable New York restaurants including Felidia, Savoy, Lumi, and Italian Wine Merchants. Anne taught for three years at New York’s Institute of Culinary Education and served as Executive Chef at New York’s Centro Vinoteca. She stars in Food Network’s Secrets of a Restaurant Chef and Worst Cooks in America and recently competed on The Next Iron Chef: Super Chefs. In 2011, she released her first cookbook, the best-selling “Cook Like a Rock Star” (Clarkson Potter). -

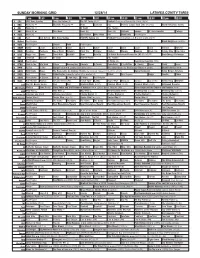

Sunday Morning Grid 12/28/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/28/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Chargers at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News 1st Look Paid Premier League Goal Zone (N) (TVG) World/Adventure Sports 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) Outback Explore St. Jude Hospital College 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Philadelphia Eagles at New York Giants. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Black Knight ›› (2001) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Play. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) República Deportiva (TVG) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Tu Dia Tu Dia Happy Feet ››› (2006) Elijah Wood. -

2 Area CFP 3-29-12.Pdf

Page 2 Colby Free Press Thursday, March 29, 2012 Area/State Weather Governors hope to save jobs Briefly Kiwanis egg hunt starts From “GOVERNORS,” Page 1 designed to reduce bacteria and help make lot of money,” Russell said. at 10 a.m. Saturday the food safer. The process Cargill uses, by the fi rm did get some good news Wednes- The annual Easter egg hunt sponsored pink slime – including Cargill and BPI – comparison, uses citric acid to achieve simi- day when Iowa-based grocer Hy-Vee said by the Colby Kiwanis Club will begin at will be able to overcome the public stigma lar results to what the fi rm does with am- it would offer beef with and without pink 10 a.m. Saturday at Fike Park. Starting against their product at this point. monia. slime because some consumers demanded times will be 10 a.m. for ages 3 and un- “I can’t think of a single solitary message The fi nished product contains only a trace the option. But larger grocery store chains, der, 10:10 a.m. for ages 4 to 6 and 10:20 that a manufacturer could use that would of ammonia, as do many other foods, and such as Kroger, have stuck with their deci- for ages 7 to 9. In case of bad weather, resonate with anybody right now,” Smith it’s meant just to be an additional “hurdle sions to stop offering beef with pink slime. listen to KXXX Radio for information. said. for the pathogens,” said Cross, who is now The real test for the future of the fi rm and For information, call Scott Haas at 460- All the governors and lieutenant gov- head of the Department of Animal Science pink slime may come later this year when 3922. -

Chef Jennifer Jasinski Chef Cat Cora

CHEF CAT CORA CHEF JENNIFER JASINSKI CEO EXECUTIVE CHEF/OWNER | RIOJA, BISTRO VENDÔME, EUCLID CAT CORA INC. | CHEFS FOR HUMANITY HALL BAR + KITCHEN, STOIC & GENUINE, ULTREIA SANTA BARBARA, CA DENVER, CO “Tailgating for the Broncos is “Even when you have something Max and I look forward doubts, take that step. to each year, we always go over the top with food that our friends are Take chances. Mistakes blown away with! We love the are never a failure - they Broncos, and getting prepped for the game is part of the fun!” can be turned into RIOJADENVER.COM wisdom.” BISTROVENDOME.COM EUCLIDHALL.COM CATCORA.COM STOICANDGENUINE.COM ULTREIADENVER.COM CHEFSFORHUMANITY.ORG CRAFTEDCONCEPTSDENVER.COM @CATCORA @CHEFJENJASINSKI @CATCORA @CHEFJENJASINSKI @CHEFCATCORA @JENNIFER.JASINSKI FEATURED DISH FEATURED DISH GUEST CHEF CAT CORA’S “LAMB MERGUEZ HOAGIE” “SMOKER TAKEOVER” LABNEH AND CARROT CUMIN SLAW Cat Cora is a world-renowned chef, author, restaurateur, television host and A James Beard Foundation award winner for Best Chef Southwest in 2013 and personality, avid philanthropist, health and fitness expert and proud mother of nominee for Outstanding Chef in 2016, Jasinski opened her first restaurant, six sons. Cat made television history in 2005, when she became the first-ever Rioja, in Denver’s Larimer Square to critical acclaim in 2004 featuring a female Iron Chef on Food Network’s Iron Chef America and founded her own Mediterranean menu influenced by local and seasonal products. She and non-profit charitable organization, Chefs for Humanity. She is the first woman business partner Beth Gruitch acquired Bistro Vendôme, a French bistro in inducted into the Culinary Hall of Fame. -

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

Franklin Becker

Franklin Becker Chef Franklin Becker is the Co-Founder and Chief Culinary Officer at Hungryroot. A graduate of the Culinary Institute of America, Chef Becker has worked in some of the country’s best kitchens. Most recently, Becker served as co-founding partner of Little Beet and Little Beet Table, as well as Culinary Director for all of Aurify brands. Prior, Becker was Corporate Executive Chef of the EMM Group (Abe & Arthurs, Lexington Brass, and Catch). In addition, Becker worked for New York’s Midtown mainstay, Brasserie, Starr Restaurant Group, Grand Hospitality, and Capitale. In 2013, Becker was invited to compete in Bravo’s Top Chef Masters. He’s a regular on television and has appeared on Iron Chef America, The Today Show, Dr. Oz, The Rachel Ray Show, Beat Bobby Flay as a judge, and more, and is the author of three cookbooks: Eat & Beat Diabetes, The Diabetic Chef, and most recently, Good Fat Cooking. Throughout his career, Becker has received glowing reviews from such acclaimed critics as Gael Greene of New York Magazine, William Grimes of The New York Times, who BUILDING BRANDS TO THEIR BOILING POINT wrote that Becker has “a talent for delivering big, punchy flavors,” and while Becker was at Capitale in 2003, Esquire’s John Mariani named it “Best New Restaurant in America.” In his spare time, Becker works extensively with charities. Near and dear to his heart are autism related causes. Becker is the Chairman of the Board of Pop Earth, has worked closely with Autism Speaks, and has helped to raise more than $14 million dollars for various autism charities. -

Take a Culinary Journey Unlike No Other. Watch a Star Rise

~Take a culinary journey unlike no other. Watch a star rise~ Let your taste buds be tantalized Meet Chef Brother Luck and his brand Four by Brother Luck & Lucky Dumpling With a name like Brother Luck it would be easy to attribute your success to good fortune, but Brother's is a result of hard work, determination, and passion. As a teenager, Brother fell on hard times when his father passed away at the age of 10. After relocating from the San Francisco Bay Area to Arizona, Brother enrolled in a vocational school for high school students to learn the culinary arts. The free food was intriguing enough to keep attending the cooking classes and eventually led him to find a passion in the kitchen that would set him up on an incredible journey inspired by a love for food and service. "I spent my whole senior year training," Brother admits. "I'd come to school in the morning and train. Then in the afternoon, I went to the Art Institute of Phoenix to train with a master chef. Then I'd work the line at the Hyatt all evening." Brother eventually was awarded with enough scholarships to attend the Art Institute of Phoenix, including one from the college, which named him “Best Teen Chef." His time in college would lead to a diverse career cooking in places around the world including in Japan; Hong Kong; Chicago; New York City and finally in Colorado Springs where he would start Brother Luck Street Eats. There he was honored as “Best Local Chef” by Colorado Springs Independent and “Most Cutting Edge Restaurant” by The Gazette Newspaper. -

Michael Symon

GUEST CHEF – MICHAEL SYMON Chef Michael Symon cooks with soul. Growing up in a Greek and Sicilian family, the Cleveland native creates boldly flavored, deeply satisfying dishes at his restaurants: Lola, Mabel’s BBQ, Roast, Bar Symon and B Spot. Most recently, he opened Angeline, an Italian restaurant in Atlantic City named after his mother. Michael also shares his exuberant, approachable cooking style and infectious laugh with viewers as an Iron Chef on the Food Network and as a co-host on ABC’s The Chew. Since being named a Best New Chef by Food & Wine magazine in 1998, Michael and his restaurants have been awarded numerous honors: in 2000 Gourmet magazine chose Lola as one of “America’s Best Restaurants;” in 2010, Michael was the first chef ever to host the annual Farm Aid benefit concert; Bon Appetit magazine included B Spot on their list of “Top 10 Best New Burger Joints;” B Spot’s Fat Doug burger won the People’s Choice award at the SoBe Wine & Food Festival. In 2009, Michael earned The James Beard Foundation Award for Best Chef Great Lakes and the Detroit Free Press named Roast “Restaurant of the Year.” Michael made his debut on Food Network in 1998 with appearances on Sara’s Secrets with Sara Moulton, Ready, Set, Cook and Food Nation with Bobby Flay, before being tapped to host over 100 episodes of The Melting Pot. He then went on to win season one of The Next Iron Chef in 2008, earning him a permanent spot on the roster of esteemed Iron Chefs. -

ALTON BROWN RETURNS to MESA ARTS CENTER! BEYOND the EATS COMING to MESA on NOV 11, 2021 Tickets On-Sale Friday, March 5 at Noon

ALTON BROWN RETURNS TO MESA ARTS CENTER! BEYOND THE EATS COMING TO MESA ON NOV 11, 2021 Tickets On-Sale Friday, March 5 at Noon March 1, 2021 (Mesa, AZ) – Mesa Arts Center is thrilled to announce “Alton Brown Live: Beyond The Eats” as the first on sale for our 2021-22 season! Mesa Arts Center will announce the full Performing Live season later this spring/summer. Mesa Arts Center’s theaters have been closed to the public since March 2020 but are anticipated to open in fall 2021. Television personality, author and Food Network star Alton Brown has announced “Alton Brown Live – Beyond The Eats” will visit Mesa Arts Center on Thursday, November 11, 2021. Brown created a new form of entertainment – the live culinary variety show – with his “Edible Inevitable Tour” and “Eat Your Science,” which played in over 200 cities with more than 350,000 fans in attendance. Tickets go on sale Friday, March 5 at noon. Get tickets at MesaArtsCenter.com or call 480-644-6500 during box office business hours. Brown says fans can expect “more cooking, more comedy, more music and more potentially dangerous science stuff.” Critics and fans have raved about the interactive components of Brown’s shows. He warns “Prepare for an evening unlike any other and if I call for volunteers… think twice.” Brown has a knack for mixing together science, music and food into two hours of pure entertainment. “Plus, you’ll see things I’ve never been allowed to do on TV.” Alton Brown has been on the Food Network for over 20 years and is best known as the creator, writer and host of Good Eats, Good Eats: Reloaded, and Good Eats: The Return. -

“Top Chef” Finalist Lindsay Autry and Restaurateur Thierry Beaud Team

“Top Chef” Finalist Lindsay Autry and Restaurateur Thierry Beaud Team Up to Bring THE REGIONAL Kitchen & Public House to West Palm Beach’s CityPlace, A Dining Destination Slated for Early 2016 —The dynamic culinary team’s new concept will occupy CityPlace’s southwest corner as the latest example of the downtown entertainment district’s recent expansion and growing appeal— West Palm Beach, Fla. (October 5, 2015)— Celebrated South Florida Chef and season 9 “Top Chef” finalist Lindsay Autry is partnering with seasoned restaurateur Thierry Beaud to open THE REGIONAL Kitchen & Public House in downtown West Palm Beach’s popular dining and entertainment destination, CityPlace. THE REGIONAL marks Autry’s first venture into restaurant proprietorship, and for Beaud, a new concept to add to his fast growing roster of exceptional dining establishments, which includes Pistache French Bistro and Paneterie Café and Bakery in West Palm Beach, PB Catch Seafood & Raw Bar and Patrick Leze‐ Palm Beach in Palm Beach, and later this season, a second Paneterie location in Delray Beach. “As a chef that has built a home and career in the Palm Beach area over the past several years, the launch of this amazing project excites me both personally and professionally,” said Autry. “I’ve had the privilege of working with this community of talented chefs, local artisans, and farmers over these years, and have seen the powerful influence they’ve had on our progressing dining scene. I’m grateful for this opportunity to highlight their talents, and couldn’t imagine a better partner with whom to build a restaurant inspired by the industry’s finest than Thierry Beaud. -

Join Top Chef Masters Winner Chef Chris Cosentino at ECS's Virtual

Join Top Chef Masters Winner Chef Chris Cosentino at ECS’s Virtual Friendsgiving! Tickets on Sale Now On November 7 at 6:30 pm, join us around Top Chef Master Chris Cosentino's ViirrttuuaallV FFrriieennddssggiivviinngg ttaabbllee. Sip an artisanal, seasonal mocktail while Chef Chris prepares a three-course culinary feast. Bay Area guests who puurrcchhaassep e ttiicckkeettss byyb OccttoobbeerO r 2222 (givergy.us/ECS) may select to have this three-course meal and mocktail delivered to your door to enjoy during the event! All guests nationwide can enjoy a virtual seat at Chef Chris’s table by puurrcchhaassiinnggp ttiicckkeettss byyb NNoovveemmbbeerr 7 (givergy.us/ECS) We look forward to celebrating Friendsgiving with you! Get Your Tickets Now! (givergy.us/ECS) Your ticket makes an impact! Funds raised will support the CHEFS (Conquering Homelessness through Employment in Food Services) culinary training program and address heightened food insecurity right here in San Francisco. Introducing Rapid Rehousing Staff Members ECS embraces a culture of dignity, equity, and opportunity for everyone involved in our organization. This is central to our mission, strategy, and programs. As such, we greatly value the lived experiences of our staff, residents, guests, and clients. Their voices are critical to ensuring that we provide the holistic services that meet each individual's needs and support them in achieving their goals. In our Reentry Rapid Rehousing Program, staff members Heather Leach and Garry Grady share how their lived experiences guide and inform their work at ECS. “When an individual who is formerly incarcerated comes into the office, they are full of apprehension,” explains one of the staff members. -

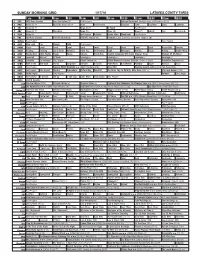

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Wisconsin. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Clangers Luna! LazyTown Luna! LazyTown 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Liberty Paid Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Seattle Seahawks at Carolina Panthers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Soulful Symphony With Darin Atwater: Song Motown 25 My Music 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Race to Witch Mountain ›› (2009, Aventura) (PG) Zona NBA Treasure Guards (2011) Anna Friel, Raoul Bova.