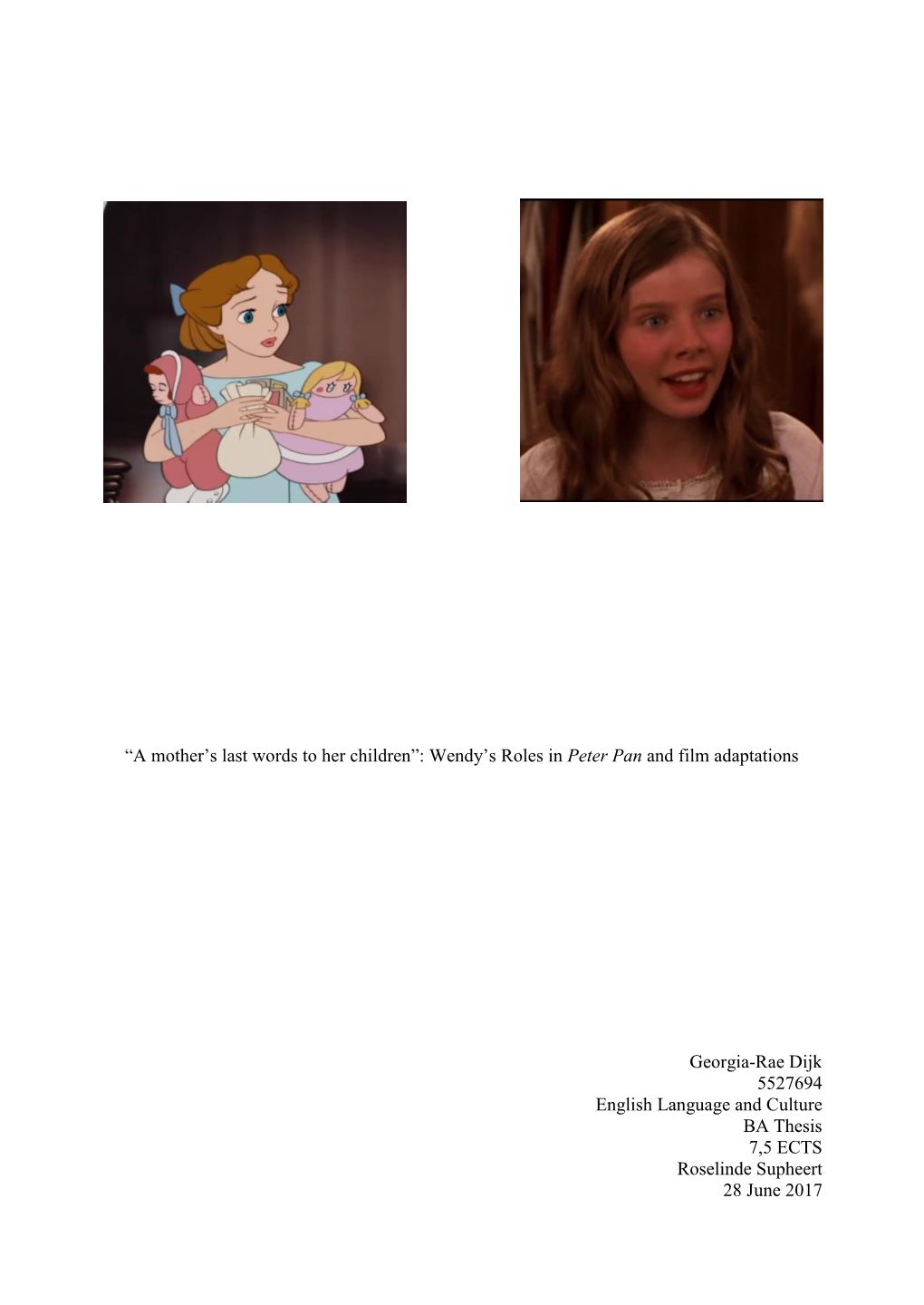

Wendy's Roles in Peter Pan and Film Adaptations Georgia-Rae Dijk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peter Pan Education Pack

PETER PAN EDUCATION PACK Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 Peter Pan: A Short Synopsis ....................................................................................................... 4 About the Writer ....................................................................................................................... 5 The Characters ........................................................................................................................... 7 Meet the Cast ............................................................................................................................ 9 The Theatre Company ............................................................................................................. 12 Who Would You Like To Be? ................................................................................................... 14 Be an Actor .............................................................................................................................. 15 Be a Playwright ........................................................................................................................ 18 Be a Set Designer ..................................................................................................................... 22 Draw the Set ............................................................................................................................ 24 Costume -

Wendy Darling: Volume 2: Seas PDF Book

WENDY DARLING: VOLUME 2: SEAS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Colleen Oakes | 273 pages | 20 Sep 2016 | Sparkpress | 9781940716886 | English | Tempe, United States Wendy Darling: Volume 2: Seas PDF Book I loved seeing Wendy in this scenario because instead of Lost Boys, this time she was dealing with the original Lost Men. When not writing or plotting new books, Oakes can be found swimming, traveling or totally immersing herself in nerdy pop culture. Glad I continued reading this series. She's gorgeous. She currently at work on another fantasy series and a stand-alone YA novel. And where these books made me hate Peter Pan and I already don't have that much love for that guy , they also made me fall a little bit in love with Hook. That was a really fun scene and it was almost WORTH being forced to sit through yet another "Hook is the good guy" novel le SIGH, but more on that later for this cute moment between them. But she comes to find that her captor is also her protector, he [Capt. Okay, I will admit it, that was pretty darn awesome! Chapter Nineteen. Wendy Darling: Seas finds Wendy and Michael aboard the dreaded Sudden Night, a dangerous behemoth sailed by the infamous Captain Hook and his blood-thirsty crew. Are you trying to make me laugh? When not writing or plotting new books, Oakes can be found swimming, traveling or totally immersing herself in nerdy pop culture. Surprising though it may be, the nothing that happens Not a lot happens in Wendy Darling: Seas. -

Open Gencarelli Alicia Peterpan.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH “TO LIVE WOULD BE AN AWFULLY BIG ADVENTURE”: MASCULINITY IN J.M. BARRIE’S PETER PAN AND ITS CINEMATIC ADAPTATIONS ALICIA GENCARELLI SUMMER 2017 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a baccalaureate degree in English with honors in English Reviewed and approved* by the following: Garrett Sullivan Liberal Arts Research Professor of English Thesis Supervisor Marcy North English Honors Advisor Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT This thesis discusses the representation of masculinity in J.M. Barrie’s novel, Peter Pan, as well as in two of its cinematic adaptations: Disney’s Peter Pan and P.J. Hogan’s Peter Pan. In particular, I consider the question: What exactly keeps Peter from growing up and becoming a man? Furthermore, I examine the cultural ideals of masculinity contemporary to each work, and consider how they affected the work’s illustration of masculinity. Then, drawing upon adaptation theory, I argue that with each adaptation comes a slightly variant image of masculinity, producing new meanings within the overall narrative of Peter Pan. This discovery provides insight into the continued relevance of Peter Pan in Western society, and subsequently, how a Victorian children’s adventure fiction is adapted to reflect contemporary ideologies and values. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................... iii Introduction -

Wendy Darling: Volume 2: Seas Free

FREE WENDY DARLING: VOLUME 2: SEAS PDF Colleen Oakes | 273 pages | 20 Sep 2016 | Sparkpress | 9781940716886 | English | Tempe, United States Seas (Wendy Darling, book 2) by Colleen Oakes She lives in North Denver with her husband and son Wendy Darling: Volume 2: Seas surrounds herself with the most lovely family and friends imaginable. When not writing or plotting new books, Oakes can be found swimming, traveling or totally immersing herself in nerdy pop culture. She currently at work on another fantasy series and a stand-alone YA novel. Wendy Darling : Volume 2: Seas. Colleen Oakes. From the author of Queen of Hearts comes the much anticipated sequel to Wendy Darling. Wendy Darling: Seas finds Wendy and Michael aboard the dreaded Sudden Night, a dangerous behemoth sailed by the infamous Captain Hook and his blood-thirsty crew. In this exotic world of mermaids, spies and pirate-feuds, Wendy finds herself struggling to keep her family above the waves. Hunted by the twisted boy who once stole her heart Wendy Darling: Volume 2: Seas struggling to survive in the whimsical Neverland sea, returning home to London now seems like a distant dream—and the betrayals have just begun. Will Wendy find shelter with Peter's greatest enemy, or is she a pawn in a much darker game, one that could forever alter not only her family's future, but also the soul of Neverland itself? Chapter Thirteen. Chapter Fourteen. Chapter Fifteen. Chapter Sixteen. Chapter Wendy Darling: Volume 2: Seas. Chapter Nineteen. Chapter TwentyOne. Pan Island. Chapter Four. Chapter Seven. Chapter Eight. Chapter Nine. -

Peter Pan and Wendy Kindle

PETER PAN AND WENDY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK J M Barrie,Robert Ingpen,David Barrie | 216 pages | 03 Aug 2010 | STERLING | 9781402728686 | English | New York, NY, United States Peter Pan and Wendy PDF Book Darling's harmless bluster and Captain Hook's pompous vanity. Wendy shares a nursery room with her two brothers, Michael and John. Avon Books. According to Barrie's description of the Darlings' house, [4] the family lives in Bloomsbury, London. She would regularly tell the boys stories of Peter's various adventures in the supposedly fictitious isle of Neverland , most notably the stories of his battles with the villainous Captain Hook. There is also a degree of innocent flirtation with Peter which incites jealousy in Peter's fairy Tinker Bell. While her age isn't specified, she is usually portrayed as a preteen on the brink of adolescence. Some time later, despite Wendy's previous escape from Neverland, she had somehow become Peter's prisoner when she and her brothers had returned to Neverland. However, the opening line of the novel, "All children, except one, grow up", and the conclusion of the story indicates that this wish is unrealistic, and there is an element of tragedy in the alternative. However, Wendy and her father do love each other and when Wendy comes back from Neverland, she seems to have a better understanding of her father. According to the narrator of the play "It has something to do with the riddle of his being. The most recent member of the cast to be added is Yara Shahidi. Wendy kisses Peter, and this breaks the spell cast over him. -

Who's Who in Flyer

Who’s Who in Flyer People ● Wendy Angela "Darling" Davis Wendy Darling; brothers: older: David (died in childhood); younger: Mike (died in college); John (died in the Army); Wendy drives a Jeep Compass (she was the compass for the Lost Boys). The Llewellyn-Davis family was the inspiration for the Darling family in Wendy and Peter. ● T. K. Bell: Thomas Kenneth Bell, "Bell" Tinker Bell; drives a Ford Explorer, just like Tink was an explorer ● Peter Barry Peter Pan ● Sylvia Barry Peter's mother; Sylvia Llewellyn Davis ● Aunt Jane, Wendy Davis' aunt Jane was Wendy Darling's daughter in Wendy and Peter ● Jamie Lim, guidance counselor Captain James Hook ● Tina "Tiger" Lilly: Peter's girlfriend Tiger Lily; Tina drowned in California ● Johnny Smead: Lim's friend who worked as a wine sommelier in Iowa City Smee, the pirate; Hook's right-hand man, who had a sword named Johnny Corkscrew ● Ted Otts, "Totts", lawyer Tootles, a Lost Boy; he grew up to be a judge ● Nanna, Wendy's childhood dog Nana, the "nanny" for the Darling family. ● Athos, the cat J.M. Barrie had a dog named Porthos ● Bill Juko, Murphy Black: reporters Bill Jukes, Black Murphy: two of Hook's pirates ● John Jones, "Dibs", a car salesman Nibs, a Lost Boy; he grew up to work in an office ● Bobby Noble, "Lightly"; a banker Slightly, a Lost Boy, who grew up to marry a noblewoman and became wealthy ● Carl "Curly" Gedney, manager of a building supply store Curly, a Lost Boy, who always gets into 'pickles' and who designed the house the Lost Boys built for Wendy ● Charmine and Fay (Filette) Charmine is French for "charmer" (a person who casts charms) and Fay is French for fairy. -

Peter Pan Is a Classic Disney Film That Celebrates the Magic of Childhood

© Disney ©The Thomas Kinkade Estate. All rights reserved. Image Sizes 12˝ x 18˝, 18˝ x 27˝, 24˝ x 36˝ | Publish Date October 2016 Peter Pan is a classic Disney film that celebrates the magic of childhood. In this tale, Wendy Darling and her brothers Michael and John join Peter Pan, Tinker Bell, and The Lost Boys on an exciting adventure that highlights how important it is to always use our imaginations and that nothing is impossible if we believe in it. The story also reinforces the fact that the power of a friendship can last a lifetime. PETE PS Peter Pan’s Never Land by Thomas Kinkade Studios captures the adventure of the magical place that Peter Pan and his friends call home. In this scene, we see Peter battling his nemesis Captain Hook, with the help of Wendy, Michael, John, The Lost Boys, and his beloved pal Tinker Bell. The friends fly together with faith and a dash of pixie dust, while the Mermaids look on and a beautiful rainbow sits brightly in the sky. This painting reminds us that although we may grow up, we should view the world with the wonderment of a child, no matter our age. It also reinforces the fact that the bonds of a true friendship can lift us up throughout our lives. © Disney Key Points • The Disney film, Peter Pan, was based on a theatrical play of the same name by Sir James Barrie. Walt Disney was touched by the story as a child. He watched it with his brother, Roy, and went on to star as Peter Pan in his school’s performance of the play. -

The Flight from Neverland: Coming of Age Through a Century of Peter Pan

THE FLIGHT FROM NEVERLAND: COMING OF AGE THROUGH A CENTURY OF PETER PAN by CAITLIN MCMAHAN A THESIS Presented to the Department of English and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June, 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor O'Fallon for all of her support throughout this endeavor. Thank you for helping me explore the ways in which literature pertains to the evolution of culture. I would also like to thank Professor Rumbarger and Professor Fracchia for agreeing to serve on my thesis committee as a secondary reader and a CHC Representative. I understand the demands on your time and I appreciate your support. Finally, I would like to thank my friends and family who not only supported my project, but offered enthusiasm and encouragement from beginning to end. This would not have been possible without all of you. iii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Peter Pan, or the Boy Who Would Not Grow Up by J.M. Barrie 11 Chapter 2: Peter Pan and Wendy by J.M. Barrie 34 Chapter 3: Walt Disney Studio’s Peter Pan 47 Chapter 4: Columbia/TriStar Picture’s Hook 59 Chapter 5: Universal Studio’s Peter Pan 71 Conclusion 88 Appendix 95 Bibliography 97 iv Introduction In her article, “Magic Abjured: Closure in Children's Fantasy Fiction,” Sarah Gilead introduces her topic by stating that “[c]hildren's literature...[reflects] the adult writer's intentions and [satisfies] adult readers' notions about children's tastes and needs, as well as fulfilling the needs of the adult societies to which the children belong” (Gilead 277). -

Peter Pan Peter Pan Is a Children’S Novel by J

Peter Pan Peter Pan is a children’s novel by J. M. Barrie. It follows the adventures of the Darling children and Peter Pan, a boy who never grows up. Peter Pan flies into Wendy Darling’s room and convinces her and her brothers to come to Neverland with him and his fairy, Tinker Bell. In Neverland, Peter and the Darlings live with the lost boys, with Wendy acting as the boys’ mother. They also battle Captain Hook and his pirate crew. The Darlings return to London, where their parents adopt the lost boys. Peter remains in Neverland, but returns to take Wendy’s daughter on an adventure. J. M. Barrie’s classic work Peter Pan (1904) tells the story of the Darling children’s journey to the magical islands of Neverland with Peter Pan, an adventurous young boy who refuses to grow up. The omniscient narrator—who addresses the audience in the first person—introduces the Darling family, which includes Mr. and Mrs. Darling; their three children, Wendy, John, and Michael; and a dog named Nana. The family resides in London, where the children share a nursery. In the present, Wendy tells Mrs. Darling about a boy named Peter Pan, who visits her dreams from a place called Neverland. After the children go to sleep, Peter Pan unexpectedly enters through their bedroom window, startling Mrs. Darling. When Mr. and Mrs. Darling leave the house to attend a nearby dinner party, Peter returns with his fairy, Tinker Bell. Wendy awakes and helps Peter attach his shadow to his body. Peter tells Wendy that he has no parents and that he refuses to ever become an adult; he lives in Neverland with a group of abandoned children who refer to themselves as “the lost boys.” Intrigued with Neverland, Wendy asks him about fairies, which reminds Peter that he accidentally trapped Tinker Bell inside a closed drawer. -

Study Guide Prepared by Catherine Bush Barter Playwright-In-Residence

Study Guide prepared by Catherine Bush Barter Playwright-in-Residence Peter Pan Adapted by Catherine Bush from the book by J.M. Barrie *Especially for Grades K-6 The Barter Players, touring Jan. thru March 2020 Barter’s Smith Theatre– April, 2020 (NOTE: Standards listed below include those for reading the story Peter Pan, seeing a performance of the play, and completing the study guide.) Virginia SOLs English – K.1, K.5, K.7, K.8, K.11, K.12, 1.1, 1.7, 1.8, 1.9, 1.12, 1.14, 2.1, 2.6, 2.7, 2.10, 2.12, 3.1, 3.2, 3.4, 3.5, 3.8, 3.10, 4.1, 4.2, 4.4, 4.5, 4.7, 4.9, 5.1, 5.2, 5.4, 5.5, 5.7, 5.9, 6.1, 6.2, 6.4, 6.5, 5.7, 5.9 Theatre Arts – 6.5, 6.7, 6.10, 6.18, 6.21 Tennessee /North Carolina Common Core State Standards English/Language Arts - Reading Literacy: K.1, K.2,K.3, K.5, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, 3.5, 3.10, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 4.5, 4.7, 4.10, 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, 5.4, 5.10, 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 6.4, 6.7, 6.10 English Language Arts – Writing: K.1, K.3, K.4, K.5, K.8, 1.1, 1.3, 1.5, 1.8, 2.1, 2.3, 2.5, 2.8, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.7, 3.8, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.7, 4.8, 4.9, 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, 5.7, 5.8, 5.9, 6.2, 6.3, 6.7, 6.9 Tennessee Fine Arts Curriculum Standards Theatre – K.T.P1, K.T.Cr2, K.T.R1.A, K.T.R2, K.T.R3, 1.T.Cr2, 1.T.Cr3, 1.T.R1, 1.T.R2, 1.T.R3, 2.T.Cr2, 2.T.Cr3, 2.T.R1, 2.T.R2, 2.T.R3, 3.T.Cr2, 3.T.Cr3, 3.T.R1, 4.T.Cr2, 4.T.Cr3, 4.T.R1, 5.T.Cr2, 5.T.Cr2, 5.T.R1, 6.T.Cr2, 6.T.R1, 6.T.R2, 6.T.R3 North Carolina Essential Standards Theatre Arts – K.A.1, K.AE.1, 1.A.1, 1.AE.1, 1.CU.2, 2.C.2, 2.A.1, 2.AE.1, 3.C.1, 3.C.2, 3.A.1, 3.CU.1, 3.CU.2, 4.C.1, 4.A.1, 4.AE.1, 5.C.1, 5.A.1, 5.AE.1, 5.CU.2, 6.C.2, 6.A.1, 6.CU.2 Setting A children’s nursery in London and the island of Neverland… Characters Wendy – a young girl with an imagination John– Wendy’s brother Michael – Wendy’s youngest brother Mrs. -

Peter Pan Adapted by Catherine Bush from the Book by J.M

Study Guide prepared by Catherine Bush Barter Playwright-in-Residence Peter Pan Adapted by Catherine Bush from the book by J.M. Barrie *Especially for Grades K-6 The Barter Players, touring Jan. thru March 2020 Barter’s Smith Theatre– April, 2020 (NOTE: Standards listed below include those for reading the story Peter Pan, seeing a performance of the play, and completing the study guide.) Virginia SOLs English – K.1, K.5, K.7, K.8, K.11, K.12, 1.1, 1.7, 1.8, 1.9, 1.12, 1.14, 2.1, 2.6, 2.7, 2.10, 2.12, 3.1, 3.2, 3.4, 3.5, 3.8, 3.10, 4.1, 4.2, 4.4, 4.5, 4.7, 4.9, 5.1, 5.2, 5.4, 5.5, 5.7, 5.9, 6.1, 6.2, 6.4, 6.5, 6.7, 6.9 Theatre Arts – 6.5, 6.7, 6.10, 6.18, 6.21 Tennessee /North Carolina Common Core State Standards English/Language Arts - Reading Literacy: K.1, K.2,K.3, K.5, 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, 3.5, 3.10, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.4, 4.5, 4.7, 4.10, 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, 5.4, 5.10, 6.1, 6.2, 6.3, 6.4, 6.7, 6.10 English Language Arts – Writing: K.1, K.3, K.4, K.5, K.8, 1.1, 1.3, 1.5, 1.8, 2.1, 2.3, 2.5, 2.8, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 3.7, 3.8, 4.1, 4.2, 4.3, 4.7, 4.8, 4.9, 5.1, 5.2, 5.3, 5.7, 5.8, 5.9, 6.2, 6.3, 6.7, 6.9 Tennessee Fine Arts Curriculum Standards Theatre – K.T.P1, K.T.Cr2, K.T.R1.A, K.T.R2, K.T.R3, 1.T.Cr2, 1.T.Cr3, 1.T.R1, 1.T.R2, 1.T.R3, 2.T.Cr2, 2.T.Cr3, 2.T.R1, 2.T.R2, 2.T.R3, 3.T.Cr2, 3.T.Cr3, 3.T.R1, 4.T.Cr2, 4.T.Cr3, 4.T.R1, 5.T.Cr2, 5.T.Cr2, 5.T.R1, 6.T.Cr2, 6.T.R1, 6.T.R2, 6.T.R3 North Carolina Essential Standards Theatre Arts – K.A.1, K.AE.1, 1.A.1, 1.AE.1, 1.CU.2, 2.C.2, 2.A.1, 2.AE.1, 3.C.1, 3.C.2, 3.A.1, 3.CU.1, 3.CU.2, 4.C.1, 4.A.1, 4.AE.1, 5.C.1, 5.A.1, 5.AE.1, 5.CU.2, 6.C.2, 6.A.1, 6.CU.2 Setting A children’s nursery in London and the island of Neverland… Characters Wendy – a young girl with an imagination John– Wendy’s brother Michael – Wendy’s youngest brother Mrs. -

Barrie's Traditional Woman: Wendy's Fatal Flaw Charlsie G

Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research Volume 6 | Issue 2 Article 4 October 2016 Barrie's Traditional Woman: Wendy's Fatal Flaw Charlsie G. Johnson Oglethorpe University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, and the Other Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Charlsie G. (2016) "Barrie's Traditional Woman: Wendy's Fatal Flaw," Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: Vol. 6 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Barrie's Traditional Woman: Wendy's Fatal Flaw Cover Page Footnote I want to give credit to Dr. Sarah Terry, who encouraged me to keep writing even when I was ready to scratch it completely. I wish to give thanks to Dr. Reshmi Hebbar and her Children's Literature course that greatly influenced this work. Gratitude to the professor that never doubted my abilities, Dr. Robert Hornback. And lastly I wish to thank those that read it and did not keep commentary to themselves. This article is available in Oglethorpe Journal of Undergraduate Research: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/ojur/vol6/iss2/4 Johnson: Wendy's Fatal Flaw Barrie’s Traditional Woman: Wendy’s Fatal Flaw “Wendy knew that she must grow up.