The Asteroids Act As a Key Step

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Honorarable Chair, Distinguished Delegates, It Is an Honour for Me to Address the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee of COPUO

February 2020 United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space 57th Session of COPUOS STSC Austria, Vienna, 3 - 14 February 2020 Statement of the International Astronautical Federation (IAF) Honorarable Chair, Distinguished Delegates, It is an honour for me to address the Scientific and Technical Subcommittee of COPUOS in my capacity as IAF Vice- President for Relations with International Organizations and representing the newly elected IAF President, Prof. Pascale Ehrenfreund, who could not join us today. Distinguished Delegates, Since its creation in 1951 the IAF has pursued its main goal to provide a platform for organizations, communities and individuals, active and enthusiastic about space, to meet, share knowledge and connect with each other in a cooperative spirit. Following its mission of Connecting @ll Space People, the IAF continuously seeks to deepen international cooperation worldwide by encouraging the advancement of knowledge about space and fostering dialogue between scientists, engineers, policy makers and all other space actors for the benefit of humanity. Please allow me to briefly highlight some of the IAF’s manifold past activities and also give you an outlook on some upcoming events: IAF Secretariat - 100 Avenue de Suffren - 75015 Paris, France T: +33 (0)1 45 67 42 60 - E: [email protected] - W: www.iafastro.org Non-profit organisation established under the French Law of 1 July 1901 The 70th International Astronautical Congress held in Washington, D.C., United States was an outstanding success with more than 6.800 participants coming from over 80 countries, for an intense week of events, meetings, and discoveries. The Congress started with the Honorable Mike Pence, Vice President of the United States, confirming the USA plans to go forward to the Moon and land the first woman and the next man on the Lunar surface by 2024. -

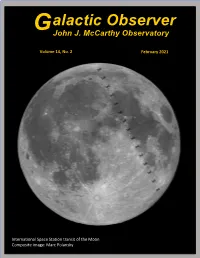

Alactic Observer

alactic Observer G John J. McCarthy Observatory Volume 14, No. 2 February 2021 International Space Station transit of the Moon Composite image: Marc Polansky February Astronomy Calendar and Space Exploration Almanac Bel'kovich (Long 90° E) Hercules (L) and Atlas (R) Posidonius Taurus-Littrow Six-Day-Old Moon mosaic Apollo 17 captured with an antique telescope built by John Benjamin Dancer. Dancer is credited with being the first to photograph the Moon in Tranquility Base England in February 1852 Apollo 11 Apollo 11 and 17 landing sites are visible in the images, as well as Mare Nectaris, one of the older impact basins on Mare Nectaris the Moon Altai Scarp Photos: Bill Cloutier 1 John J. McCarthy Observatory In This Issue Page Out the Window on Your Left ........................................................................3 Valentine Dome ..............................................................................................4 Rocket Trivia ..................................................................................................5 Mars Time (Landing of Perseverance) ...........................................................7 Destination: Jezero Crater ...............................................................................9 Revisiting an Exoplanet Discovery ...............................................................11 Moon Rock in the White House....................................................................13 Solar Beaming Project ..................................................................................14 -

Space Diplomacy & Making “Space for Women” Leaders

Space Diplomacy & Making “Space for Women” Leaders UNITED NATIONS EXPERT MEETING ON ‘SPACE FOR WOMEN” 4th – 6th October 2017 New York, USA Namira Salim Founder & Executive Chairperson Space Trust Space Diplomacy & Making “Space for Women” Leaders A New Space Age Commercialization or Democratization of Space Opens the Final Frontier to All Sectors 10% 37% 14% 2016 $329 Billion Global Space Economy Total Annual Revenue 39% Non US Govt Space Budgets US Govt Space Budgets Comm. Space P + S Comm. Infrastructure & Industry Space Report 2016 - Space Foundation Encouraging Public- Triggering a New Complex Space Private Partnerships Space Economy Environment From the Edge of Space to Low Earth Orbit, to the Moon, Mars & Beyond Space Diplomacy & Making “Space for Women” Leaders SPACE DIPLOMACY & MAKING “SPACE FOR WOMEN” LEADERS Our NewSpace Age or “Democratisation of Space” provides low-cost access to space and makes space "Inclusive for All." Spacefaring & New Space Nations expanding cooperation in Low Earth Orbit, to asteroids, the Moon, Mars & beyond via human & robotic missions Deep Space Habitats & colonies on Mars will Evolve Humans into Inter- Planetary Ambassadors As the final frontier opens to all sectors, why not open space to world leaders and above all, women in global leadership roles to find innovative solutions for a peaceful world? Raise awareness for Space Diplomacy on the institutional level Advocate & encourage Women Leaders in Political Sectors & Female Heads of State to exercise space diplomacy in an increasingly complex -

June 2020 PRAYAS4 IAS �यास सनु हर े भ�व�य क

June 2020 PRAYAS4 IAS यास सनु हर े भवय क Current Affairs Special Issue MCQs [email protected] www.theprayasindia.com/upsc An initiative for UPSC Aspirants S o u r c e s The Hindu | Live Mint | The Economic Times | The Indian Express | PRS PIB | PRS | ET | Government & World Reports (NITI, Aayog, Budget WEF Economic Survey etc.) | Hindu Business Line | NCERTs | All standard reference books The Prayas ePathshala www.theprayasindia.com/e-pathshala/ June (Week 1) Index Prelims Mains National GS I 1. Rajya Sabha elections 2. BHIM App 1. COVID-19 exposes fault lines in peri- 3. Cyclone Nisarga urban areas 4. PM SVANidhi 2. COVID-19 and our new normal 5. Essential Commodities Act 6. Inner Line permit 7. Kolkata Port GS II 8. SWADES 9. Amery Ice Shelf 1. Military bonding beyond borders 10. World Environment Day 2020 2. COVID-19: Exclusion, isolation of 11. TULIP differently abled 12. Nagar Van Scheme 13. Van Dhan Scheme International 1. Travel Bubble 2. Antifa 3. Line of Actual Control 4. G-7 5. The National Guard 6. THAAD Defence System www.theprayasindia.com/e-pathshala [email protected] +91-7710013217 / 9892560176 The Prayas ePathshala www.theprayasindia.com/e-pathshala/ Prelims NATIONAL Rajya Sabha elections (Source: The Hindu ) Context: The elections to 18 Rajya Sabha seats that were deferred owing to the lockdown will be held on June 19. How elections are conducted in Rajya Sabha? The Rajya Sabha or the Upper House of Parliament is modeled after the House of Lords in the United Kingdom. The Rajya Sabha currently has 245 members, including 233 elected members and 12 nominated. -

How the Current View of the Air and Space Environment

AU/ACSC/006/1998-04 AIR COMMAND AND STAFF COLLEGE AIR UNIVERSITY HOW THE CURRENT VIEW OF THE AIR AND SPACE ENVIRONMENT INFLUENCES DEVELOPMENT OF MILITARY SPACE FORCES by Lyndon S. Anderson, Major, USAF Stephen M. Rothstein, Major, USAF A Research Report Submitted to the Faculty In Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements Advisor: Lt Col Theresa R. Clark Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama April 1998 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US government or the Department of Defense. In accordance with Air Force Instruction 51-303, it is not copyrighted, but is the property of the United States government. ii Contents Page DISCLAIMER................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF TABLES.......................................................................................................... v PREFACE...................................................................................................................... vi ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................ viii INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 THE CURRENT PARADIGM........................................................................................ 4 Describing the Current Paradigm.............................................................................. -

Issue #1 – 2012 October

TTSIQ #1 page 1 OCTOBER 2012 Introducing a new free quarterly newsletter for space-interested and space-enthused people around the globe This free publication is especially dedicated to students and teachers interested in space NEWS SECTION pp. 3-22 p. 3 Earth Orbit and Mission to Planet Earth - 13 reports p. 8 Cislunar Space and the Moon - 5 reports p. 11 Mars and the Asteroids - 5 reports p. 15 Other Planets and Moons - 2 reports p. 17 Starbound - 4 reports, 1 article ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ARTICLES, ESSAYS & MORE pp. 23-45 - 10 articles & essays (full list on last page) ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- STUDENTS & TEACHERS pp. 46-56 - 9 articles & essays (full list on last page) L: Remote sensing of Aerosol Optical Depth over India R: Curiosity finds rocks shaped by running water on Mars! L: China hopes to put lander on the Moon in 2013 R: First Square Kilometer Array telescopes online in Australia! 1 TTSIQ #1 page 2 OCTOBER 2012 TTSIQ Sponsor Organizations 1. About The National Space Society - http://www.nss.org/ The National Space Society was formed in March, 1987 by the merger of the former L5 Society and National Space institute. NSS has an extensive chapter network in the United States and a number of international chapters in Europe, Asia, and Australia. NSS hosts the annual International Space Development Conference in May each year at varying locations. NSS publishes Ad Astra magazine quarterly. NSS actively tries to influence US Space Policy. About The Moon Society - http://www.moonsociety.org The Moon Society was formed in 2000 and seeks to inspire and involve people everywhere in exploration of the Moon with the establishment of civilian settlements, using local resources through private enterprise both to support themselves and to help alleviate Earth's stubborn energy and environmental problems. -

Space Resources : Social Concerns / Editors, Mary Fae Mckay, David S

Frontispiece Advanced Lunar Base In this panorama of an advanced lunar base, the main habitation modules in the background to the right are shown being covered by lunar soil for radiation protection. The modules on the far right are reactors in which lunar soil is being processed to provide oxygen. Each reactor is heated by a solar mirror. The vehicle near them is collecting liquid oxygen from the reactor complex and will transport it to the launch pad in the background, where a tanker is just lifting off. The mining pits are shown just behind the foreground figure on the left. The geologists in the foreground are looking for richer ores to mine. Artist: Dennis Davidson NASA SP-509, vol. 4 Space Resources Social Concerns Editors Mary Fae McKay, David S. McKay, and Michael B. Duke Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas 1992 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Scientific and Technical Information Program Washington, DC 1992 For sale by the U.S. Government Printing Office Superintendent of Documents, Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-9328 ISBN 0-16-038062-6 Technical papers derived from a NASA-ASEE summer study held at the California Space Institute in 1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Space resources : social concerns / editors, Mary Fae McKay, David S. McKay, and Michael B. Duke. xii, 302 p. : ill. ; 28 cm.—(NASA SP ; 509 : vol. 4) 1. Outer space—Exploration—United States. 2. Natural resources. 3. Space industrialization—United States. I. McKay, Mary Fae. II. McKay, David S. III. Duke, Michael B. IV. United States. -

Moon, Mars & Beyond

TTHHEE SSPPAACCEE EEXXPPLLOORRAATTIIOONN AALLLLIIAANNCCEE ENDORSE MOON, MARS & BEYOND: FUND THE FY2005 NASA EXPLORATION BUDGET REQUEST We Are The Space Exploration Alliance, an unprecedented partnership of twenty of the nation’s premier space advocacy groups, industry associations and space policy organizations. We Have Joined Together To urge endorsement and full funding of the new Vision for Space Exploration that will refocus NASA’s human space activities toward exploration, including a return to the Moon and moving on to Mars and beyond. Why Should You Endorse and Fund These Goals? Here are just two reasons: REASON #1: IT’S AFFORDABLE Critics of Moon, Mars & Beyond have largely focused on cost. Some falsely claim those costs will run into the trillions of dollars. Some erroneously suggest huge increases in the NASA budget will be required. HERE’S THE REAL STORY: “It is a “go as you can pay” plan where we achieve periodic milestones, technological advances, and discoveries based on what we can afford annually.” From the report of the President’s Commission on Implementation of United States Space Exploration Policy June 16, 2004 With the clarity of a long-term vision focused on Moon, Mars & Beyond, NASA funding can be directed toward a set of coherent goals. Modest but steady growth in our national expenditures on space will move the nation toward these important goals, and the benefits those expenditures will provide. Aerospace Industries Association . Aerospace States Association . American Astronautical Society American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics . California Space Authority Federation of Galaxy Explorers . Florida Space Authority . Global Space Travelers . The Mars Society Moon Society . -

SPACESET 14Th Annual Space Settlement Design Competition for High School Students

The Space Educator Available in print and PDF downloadable format at http://www.nss.org The Space Educator responds to the many requests for information the National Space Society receives from K-12 educators, university students, and the general public. Programs and web sites change frequently as space exploration goals are achieved, educational technology advances and budgets expand or contract. Therefore, recipients should be advised that if they discover a listing is no longer viable or a better one exists, they should contact NSS so that future updates can be maintained. The organization of this publication is based on the educational framework developed at NASA Headquarters. Due to the large number of space education activities and products, we have not tried to evaluate or describe them individually. First the National Space Society is described and its role as a portal to space information. Next are the sources of curriculum support for space science, the human exploration of space, space transportation technology, and space policy. Following naturally from this is a list of web sites which link the user to federal resources, space businesses, and organizations which provide other types of media, data/project opportunities, contests, and scholarships. Museums and Visitor Centers where space is the primary focus of the exhibits and a general calendar of space-related events including annual conferences and tours are listed. Finally, as a quick reference guide, we have presented the most frequently asked questions which we receive -

Myth-Free Space Advocacy Part III: the Myth of Educational Inspiration

Space Policy xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Space Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/spacepol Myth-free space advocacy part III: The myth of educational inspiration James S.J. Schwartz Department of Philosophy, Wichita State University, 1845 N Fairmount, Wichita, 67260, KS, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: I argue against a common belief among space advocates that spaceflight is “educationally inspiring” in that it has STEM education a clear, positive impact on scientific literacy and on STEM education. On the basis of a variety of survey analyses Scientific literacy I show that, while there is some indication that being scientifically literate makes a person more likely to support Federal space spending spaceflight, there is no clear indication that the extent of spaceflight activities (or the extent of funding for Educational inspiration spaceflight) makes people more likely to be scientifically literate or to be supportive of spaceflight (at least in the Space advocacy United States). Regarding STEM education, while there is a correlation between US spaceflight spending and STEM degree conferrals, a similar correlation obtains between spaceflight spending and degree conferrals in virtually every other discipline, and between overall US spending on science and degree conferrals in virtually every discipline. Thus there is no clear evidence that spaceflight spending is uniquely inspirational for STEM. It follows that there is little evidence that clearly supports the idea that spaceflight is educationally inspiring in the ways that many space advocates have claimed, in both academic and popular settings. 1. Introduction increases in STEM education. This paper is the third in a series on unsubstantiated beliefs that And concerning STEM education in particular the inspiration argument pervade the space advocacy literature and rhetoric, both academic and takes this form: popular. -

Conclusion Space Politics and Policy: Facing the Future

CONCLUSION SPACE POLITICS AND POLICY: FACING THE FUTURE John M. Logsdon* The essays in this volume individually and collectively do an excellent job of laying out the many dimensions of space activities to date, provide various conceptual frameworks for the analysis of those activities, and guide the reader to the body of policy-oriented literature that has grown up around the space sector. Taken together, they comprise an extremely valuable resource for understanding the political and policy aspects of the space sector as its development has gone forward. This concluding chapter reflects on how the policy issues related to space activity have changed and continue to change today. The general perspective is that new approaches and new understandings are needed, ones that will challenge not only those who have been working on space issues for some time, but also the new generation of space analysts who will read this and similar works. This challenge lies in learning and applying multiple frameworks to the analysis of space policy. The thoughts expressed in this concluding chapter reflect the views and “authority” of someone who has observed space affairs close-up, but from some analytical distance, since the beginnings of the space age.1 These thoughts are a product of the “golden age” of space development as exemplified by the Sputnik launches in 1957, Yuri Gagarin’s pioneering flight in 1961, John Glenn’s three-orbit mission in February 1962, and the Apollo lunar landing of 1969. ONCE WE WENT TO THE MOON Space politics and policy is a product of this golden age of space development, when President Kennedy committed the US to sending Americans to the Moon. -

ISDC 2018 Schedule Thursday, May 24

ISDC 2018 Schedule page 2 As of 4-19-18 Thursday, May 24 Registration Century Prefunction 8:00 am - 6:00 pm Student Registration Grand ABC 9:00 am - 6:00 pm Exhibit Hall Gateway & Century Prefunction 10:00 am - 6:00 pm Morning Plenary Grand Ballroom 8:30 am - 9:45 am Welcome & MC: John C. Mankins, ISDC 2018 Conference Chair, President, Mankins Space Technology, National Space Society Board of Directors Opening Remarks: Mark Hopkins, Chairman of the Executive Committee, National Space Society Board of Directors Felicitation Ceremony Keynote Speaker: Thomas Mueller, Propulsion Chief Technology Officer, SpaceX Presenting of NSS Space Pioneer Award to Thomas Mueller Student Plenary Grand Ballroom 10:00 am - 10:45 am Keynote Speaker: tbd 10:00 am - 12:00 noon Morning Sessions Living In Space Salon 210 (2nd floor) 10:00 am Mars Settlement, Not Just Marstopia. Vera Mulyani (Spaceport LA) 10:30 am Designing Aesthetics into Space Environments. Ayse Oren 10:50 am Building A Lunar Base as the Foundation for a Future Mars Settlement. Joshua Castro (Instarz Technologies) 11:10 am NSS/NASA Ames Student Space Settlement Contest Presentation 11:20 am The Mt. Everest Colony: Testing a Mars Colony Prototype. Greg Manos (Filmmakers Turned Technologists) 11:40 am Virtual Reality Tools for Serious Spacefight: How Space Advocacy Orgs Can Work Together. James Burk (The Mars Society) Space Settlements Hermosa Room 10:00 am ELEO Settlement: Progress and Setbacks. Al Globus (San Jose State University) 10:30 am Lighting Requirements for Agriculture in Space. Stephen D. Covey (Deep Space Industries) 11:00 am Soil for Space Habitats from Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS) Bi-Products Combined with Regolith.