A Fixated People

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Secret Flower and Other Stories the Secret Flower and Other Stories

the secret flower and other stories The Secret Flower and other stories Jane Tyson Clement Illustrations by Don Alexander Please share this e-book with your friends. Feel free to e-mail it or print it in its entirety or in part, but please do not alter it in any way. If you wish to make multiple copies for wider distribution, or to reprint portions in a newsletter or periodical, please observe the following restrictions: 1) You may not reproduce it for commercial gain. 2) You must include this credit line: “Reprinted from www.bruderhof.com. Copyright 2003 by The Bruderhof Foundation, Inc. Used with permission.” The four verses from “The Secret Flower” (p. vii) are reprinted from The Oxford Book of Carols by permission of the Oxford University Press. This e-book was published by The Bruderhof Foundation, Inc., Farmington, PA 15437 USA and the Bruderhof Communities in the UK, Robertsbridge, East Sussex, TN32 5DR, Copyright 2003 by The Bruderhof Foundation. Inc., Farmington, PA 15437 USA. All Rights Reserved Contents ( ) The Sparrow 1 ( ) The Storm 5 ( ) The Innkeeper’s Son 0 ( ) The King of the Land in the Middle 1 ( ) The White Robin 7 ( ) The Secret Flower 5 ( ) www.Bruderhof.com This child was born to men of God: Love to the world was given; In him were truth and beauty met, On him was set At birth the seal of heaven. He came the Word to manifest, Earth to the stars he raises: The teacher’s errors are not his, The Truth he is: No man can speak his praises. -

Biomimicry: Emulating the Closed-Loops Systems of the Oak Tree for Sustainable Architecture Courtney Drake University of Massachusetts Amherst

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 2011 Biomimicry: Emulating the Closed-Loops Systems of the Oak Tree for Sustainable Architecture Courtney Drake University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Part of the Architecture Commons Drake, Courtney, "Biomimicry: Emulating the Closed-Loops Systems of the Oak Tree for Sustainable Architecture" (2011). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 602. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/602 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BIOMIMICRY: EMULATING THE CLOSED-LOOPS SYSTEMS OF THE OAK TREE FOR SUSTAINABLE ARCHITECTURE A Thesis Presented by COURTNEY DRAKE Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARCHITECTURE May 2011 Architecture + Design Program Department of Art, Architecture and Art History © Copyright by Courtney Drake 2011 All Rights Reserved BIOMIMICRY: EMULATING THE CLOSED-LOOPS SYSTEMS OF THE OAK TREE FOR SUSTAINABLE ARCHITECTURE A Thesis Presented by COURTNEY DRAKE Approved as to style and content by: _______________________________________ Kathleen Lugosch, Chair _______________________________________ Sigrid Miller Pollin, Member ____________________________________ William T. Oedel, Chair Department of Art, Architecture, and Art History DEDICATION To David Dillon ABSTRACT BIOMIMICRY: EMULATING THE CLOSED-LOOPS SYSTEMS OF THE OAK TREE FOR SUSTAINABLE ARCHITECTURE MAY 2011 COURTNEY DRAKE, B.F.A., SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY M. -

Vincent Van Gogh the Starry Night

Richard Thomson Vincent van Gogh The Starry Night the museum of modern art, new york The Starry Night without doubt, vincent van gogh’s painting the starry night (fig. 1) is an iconic image of modern culture. One of the beacons of The Museum of Modern Art, every day it draws thousands of visitors who want to gaze at it, be instructed about it, or be photographed in front of it. The picture has a far-flung and flexible identity in our collective musée imaginaire, whether in material form decorating a tie or T-shirt, as a visual quotation in a book cover or caricature, or as a ubiquitously understood allusion to anguish in a sentimental popular song. Starry Night belongs in the front rank of the modern cultural vernacular. This is rather a surprising status to have been achieved by a painting that was executed with neither fanfare nor much explanation in Van Gogh’s own correspondence, that on reflection the artist found did not satisfy him, and that displeased his crucial supporter and primary critic, his brother Theo. Starry Night was painted in June 1889, at a period of great complexity in Vincent’s life. Living at the asylum of Saint-Rémy in the south of France, a Dutchman in Provence, he was cut off from his country, family, and fellow artists. His isolation was enhanced by his state of health, psychologically fragile and erratic. Yet for all these taxing disadvantages, Van Gogh was determined to fulfill himself as an artist, the road that he had taken in 1880. -

Pocket Calendar & Stakes Schedule

2020-2021 POCKET SCHEDULE 149th THOROUGHBRED RACING SEASON NOVEMBER 2020 DECEMBER 2020 JANUARY 2021 SS M T W TH F SS SS MM TT WW TH F S S SS M TT WW THTH FF SS * * * * * * * * * 3 4 5 1 2 * * * * * * * 6 * * * 10 11 12 3 * * 6 7 8 9 * * * * * * * 13 * * 16 17 18 19 10 * * * 14 15 16 * * * * 26 27 28 20 * * * * * 26 17 18 * * 21 22 23 29 * 27 28 * * 31 24 * * * 28 29 30 31 FEBRUARY 2021 MARCH 2021 PROGRAMMING S M T W TH F S S M T TH F S NOVEMBER 26 S M T W TH F S S M T W TH F S THANKSGIVING CLASSIC DECEMBER 12 * * 3 4 5 6 * * * 4 5 6 LOUISIANA CHAMPIONS DAY (LA) 7 * * * 11 12 13 7 * * * 11 12 13 DECEMBER 19 SANTA SUPER SATURDAY * 15 16 * 18 19 20 14 * * * 18 19 20 JANUARY 16 ROAD TO THE DERBY KICKOFF DAY 21 * * * 25 26 27 21 * * * 25 26 27 FEBUARY 13 LOUISIANA DERBY PREVIEW DAY 28 28 * * * MARCH 20 LOUISIANA DERBY DAY POST TIME 1PM UNLESS STATED BELOW: POST TIME - 11:00 AM POST TIME - 12:00 PM \ GRADED STAKES DAYS (DEC. 12, JAN. 16, FEB. 13 & MAR. 20) POST TIMES ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE. 2020-2021 THOROUGHBRED RACING SEASON STAKES SCHEDULE DATE PURSE STAKES RUNNING CONDITIONS DISTANCE / SURFACE NOV 26 125,000 THANKSGIVING CLASSIC 96th 3YO/UP 6 FURLONGS DEC 5 75,000 PAN ZARETA STAKES 55th 3YO/UP FILLIES & MARES 5 1/2 FURLONGS* (T) DEC 11 50,000 THE MAGIC CITY CLASSIC 10th 3YO/UP ONE MILE DEC 12 LOUISIANA CHAMPIONS DAY (LA) 100,000 LA CHAMPIONS DAY QH JUVENILE STAKES - GRADE II 30th 2YO 350 YARDS 100,000 LA CHAMPIONS DAY QH DERBY - GRADE III 30th 3YO 400 YARDS 100,000 LA CHAMPIONS DAY QH CLASSIC - GRADE II 30th 4YO/UP 440 YARDS 100,000 LA CHAMPIONS -

Midwest Non-Deal Roadshow

Midwest Non-Deal Roadshow Prepared For: Investor Relations (NASDAQ: CHDN) October 7-8, 2014 Bill Mudd, President and CFO Mike Anderson, VP Finance & IR / Treasurer Forward-Looking Statements This document contains various “forward-looking statements” within the meaning of Section 27A of the Securities Act of 1933 and Section 21E of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. The Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 (the “Act”) provides certain “safe harbor” provisions for forward-looking statements. All forward-looking statements are made pursuant to the Act. The reader is cautioned that such forward-looking statements are based on information available at the time and/or management’s good faith belief with respect to future events, and are subject to risks and uncertainties that could cause actual performance or results to differ materially from those expressed in the statements. Forward-looking statements speak only as of the date the statement was made. We assume no obligation to update forward-looking information to reflect actual results, changes in assumptions or changes in other factors affecting forward-looking information. Forward-looking statements are typically identified by the use of terms such as “anticipate,” “believe,” “could,” “estimate,” “expect,” “intend,” “may,” “might,” “plan,” “predict,” “project,” “hope,” “should,” “will,” and similar words, although some forward-looking statements are expressed differently. Although we believe that the expectations reflected in such forward-looking statements are reasonable, -

The Big Easy and All That Jazz

©2014 JCO, Inc. May not be distributed without permission. www.jco-online.com The Big Easy and All that Jazz fter Hurricane Katrina forced a change of A venue to Las Vegas in 2006, the AAO is finally returning to New Orleans April 25-29. While parts of the city have been slow to recover from the disastrous flooding, the main draws for tourists—music, cuisine, and architecture—are thriving. With its unique blend of European, Caribbean, and Southern cultures and styles, New Orleans remains a destination city for travelers from around the United States and abroad. Transportation and Weather The renovated Ernest N. Morial Convention Center opened a new grand entrance and Great Hall in 2013. Its location in the Central Business District is convenient to both the French Quarter Bourbon Street in the French Quarter at night. Photo © Jorg Hackemann, Dreamstime.com. to the north and the Garden District to the south. Museums, galleries, and other attractions, as well as several of the convention hotels, are within Tours walking distance, as is the Riverfront Streetcar line that travels along the Mississippi into the Get to know popular attractions in the city French Quarter. center by using the hop-on-hop-off double-decker Louis Armstrong International Airport is City Sightseeing buses, which make the rounds about 15 miles from the city center. A shuttle with of a dozen attractions and convenient locations service to many hotels is $20 one-way; taxi fares every 30 minutes (daily and weekly passes are are about $35 from the airport, although fares will available). -

An Investigation of Children's Abilities to Form and Generalize Visual Concepts from Visually Complex Art Reproductions

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 061 228 TE 499 769 AUTHOR Clark, Gilbert A. TITLE An Investigation of Children's Abilities to Form and Generalize Visual Concepts from Visually Complex Art Reproductions. Final Report. INsTITUTION Ohio state Univ., Columbus. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DHEw), Washington, D.C. Bureau of Research. BUREAU NO BR-0-I-060 PUB DATE Jan 72 GRANT OEG-9-70-0031(057) NOTE 85p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Ability Identification; *Art; *children; Classification; *Concept Formation; Correlation; Data Analysis; Data Collection; Discrimination Learning; Individual Differences; Interaction; Rating Scales; Research; Standards; Stimuli; Student Evaluation; Tape Recordings; Task Performance: Test Results; Verbal Ability; *Visual Perception ABSTRACT The re earch reported here was designed to measure the abilities of school-age children to form and generalize "visual concepts" on the basis of their observation of prepared sets of art reproductions. The art reproduction sets displayed similarities based upon various visual attributes. Discrimination of theattributes common to any given set was taken as evidence of concept formation. Selection of similar reproductions in additional displays was taken as evidence of concept generalization. Additionally,tape-recorded discussions of the test administrations were analyzed. These discussions yielded additional evidence of successful test performance (on a verbal dimension) and were useful in describing the character of children's abilities to discuss the visual attributes of art reproductions. Evidence gathered indicates that students at all grades (except, possibly, kindergarten) are able to form visual concepts from their observation of selected sets of art reproductions. Subjects also successfully described their classification of observed visual similarities when discussing the items. -

Living Blues 2021 Festival Guide

Compiled by Melanie Young Specific dates are provided where possible. However, some festivals had not set their 2021 dates at press time. Due to COVID-19, some dates are tentative. Please contact the festivals directly for the latest information. You can also view this list year-round at www.LivingBlues.com. Living Blues Festival Guide ALABAMA Foley BBQ & Blues Cook-Off March 13, 2021 Blues, Bikes & BBQ Festival Juneau Jazz & Classics Heritage Park TBA TBA Foley, Alabama Alabama International Dragway Juneau, Alaska 251.943.5590 2021Steele, Alabama 907.463.3378 www.foleybbqandblues.net www.bluesbikesbbqfestival.eventbrite.com jazzandclassics.org W.C. Handy Music Festival Johnny Shines Blues Festival Spenard Jazz Fest July 16-27, 2021 TBA TBA Florence, Alabama McAbee Activity Center Anchorage, Alaska 256.766.7642 Tuscaloosa, Alabama spenardjazzfest.org wchandymusicfestival.com 205.887.6859 23rd Annual Gulf Coast Ethnic & Heritage Jazz Black Belt Folk Roots Festival ARIZONA Festival TBA Chandler Jazz Festival July 30-August 1, 2021 Historic Greene County Courthouse Square Mobile, Alabama April 8-10, 2021 Eutaw, Alabama Chandler, Arizona 251.478.4027 205.372.0525 gcehjazzfest.org 480.782.2000 blackbeltfolkrootsfestival.weebly.com chandleraz.gov/special-events Spring Fling Cruise 2021 Alabama Blues Week October 3-10, 2021 Woodystock Blues Festival TBA May 8-9, 2021 Carnival Glory Cruise from New Orleans, Louisiana Tuscaloosa, Alabama to Montego Bay, Jamaica, Grand Cayman Islands, Davis Camp Park 205.752.6263 Bullhead City, Arizona and Cozumel, -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p. -

Heart of Darkness: Why Electricity for Africa Is a Security Issue Geoff Hill Essay 13, the Global Warming Policy Foundation

HEART OF DARKNESS WHY ELECTRICITY FOR AFRICA IS A SECURITY ISSUE Geoff Hill The Global Warming Policy Foundation Essay 13 Heart of Darkness: Why electricity for Africa is a security issue Geoff Hill Essay 13, The Global Warming Policy Foundation © Copyright 2020, The Global Warming Policy Foundation Contents About the author iii Be afraid of the dark 1 Part 1: Problems 3 Part 2: Solutions 11 The light fantastic 14 Conclusion 16 Appendix: Singing the spirits back of beyond 17 Notes 19 About the Global Warming Policy Foundation 20 About the author Geoff Hill is a Zimbabwean writer working across Africa. His media career began at the Manica Post in Mutare in 1980 and he has worked on all six continents. In Sydney, from 1983 to 1989, he was special reports manager for Rupert Murdoch's flagship paper, The Australian, leaving to start his own publishing firm, which he sold in 2000. In that year, Hill became the first non-American to win a John Steinbeck Award for his writing, along with a BBC prize for the best short story from Africa. In the publicity that followed, he was approached to write a definitive account of his home country. The Battle for Zimbabwe became a bestseller in South Africa, and the US edition was launched in Washington by Assistant Secretary of State for Africa, Walter Kansteiner (who served under George W. Bush). The London launch was at the Royal Institute for International Affairs (Chatham House). The sequel, What Happens After Mugabe? enjoyed nine reprints and sold glob- ally with a cover endorsement from author, John le Carré. -

5555 Bullard Ave New Orleans, LA Investment Advisors

JDS Real Estate Services Bullard Corporate Center 5555 Bullard Ave New Orleans, LA Investment Advisors ENRI PINTO VP of National Sales CONFIDENTIALITY Miami Office AND DISCLOSURE Phone: 305-924-3094 [email protected] The information contained in the following Offering Memorandum (“OM”) is proprietary and strictly confidential. It is intended to be reviewed only by the party receiving it from Apex Capital Realty and should not be made available to any other person, entity, or affiliates without the written consent of Apex Capital Realty. By taking possession of and reviewing STEVEN VANNI the information contained herein the recipient agrees to hold and treat all such information Managing Director in the strictest confidence. The recipient further agrees that recipient will not photocopy or Miami Office duplicate any part of the offering memorandum. If you have no interest in the subject prop- Phone: 305-989-7854 erty at this time, please return this offering memorandum to Apex Capital Realty. This OM has been prepared to provide summary, unverified information to prospective purchasers, [email protected] and to establish only a preliminary level of interest in the subject property. The information contained herein is not a substitute for a thorough due diligence investigation. Apex Capital Realty has not made any investigation, and makes no warranty or representation, with respect to the income or expenses for the subject property, the future projected financial per- TONY SOTO formance of the property, the size and square footage of the property, the physical condition of the improvements thereon, or the financial condition or business prospects of any tenant, Commercial Advisor or any tenant’s plans or intentions to continue its occupancy of the subject property. -

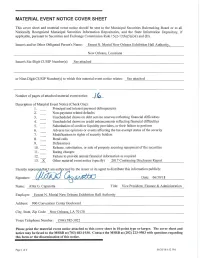

2017 Continuing Disclosure Report

MATERIAL EVENT NOTICE COVER SHEET This cover sheet and material event notice should be sent to the Municipal Securities Rulemaking Board or to all Nationally Recognized Municipal Securities Information Repositories, and the State Information Depository, if applicable, pursuant to Securities and Exchange Commission Rule 15c2-12(b)(5)(i)8) and (D). Issuer's and/or Other Obligated Person's Name: Ernest N. Moria! New Orleans Exhibition Hall Authority, New Orleans, Louisiana Issuer's Six-Digit CUSIP Number(s): See attached --------------------------------------------------------- or Nine-Digit CUSIP Number(s) to which this material event notice relates: ---=-S-=-ee=--=att=ac::..:.h.:...:e-=d______ _____________ Number of pages of attached material event notice: ~ Description of Material Event Notice (Check One): 1. Principal and interest payment delinquencies 2. Non-payment related defaults 3. Unscheduled draws on debt service reserves reflecting financial difficulties 4. Unscheduled draws on credit enhancements reflecting financial difficulties 5. Substitution of credit or liquidity providers, or their failure to perform 6. Adverse tax opinions or events affecting the tax-exempt status of the security 7. Modifications to ri ghts of security holders 8. Bond calls 9. Defeasances 10. Release, substitution, or sale of property securing repayment of the securities 11. Rating changes 12. Failure to provide annual financial information as required 13. X Other material event notice (spec ifY) 20 17 Continuing Disclosure Report that,. I am authorized by the issuer or its agent to distribute this information publicly: Signature: Date: 06/3 0118 Name: Alita G. Caparotta Title: Vice President, Finance & Administration Employer: Ernest N. Moria! New Orleans Exhibition Hall Authority Address: 900 Convention Center Boulevard City, State, Zip Code New Orleans, LA 701 30 Voice Telephone Number: ----'-'(5'--'0'--'4.L)-=-- 5-=--82__ --=--3-=--02 _2_____________ ___ ___ _______ Please print the material event notice attached to this cover sheet in 10-point type or larger.