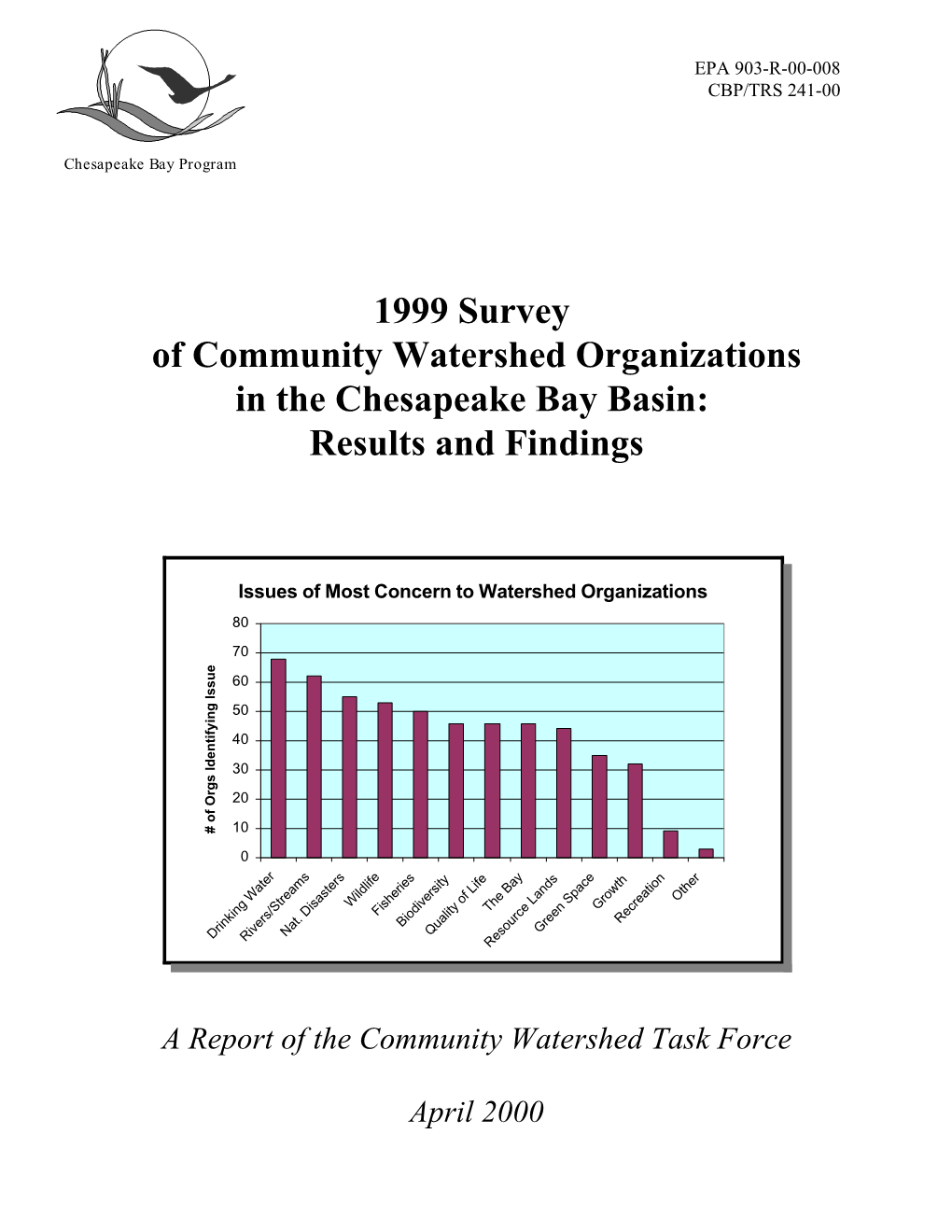

1999 Survey of Community Watershed Organizations in the Chesapeake Bay Basin: Results and Findings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luzerne County Act 167 Phase II Stormwater Management Plan

Executive Summary Luzerne County Act 167 Phase II Stormwater Management Plan 613 Baltimore Drive, Suite 300 Wilkes-Barre, PA 18702 Voice: 570.821.1999 Fax: 570.821.1990 www.borton-lawson.com 3893 Adler Place, Suite 100 Bethlehem, PA 18017 Voice: 484.821.0470 Fax: 484.821.0474 Submitted to: Luzerne County Planning Commission 200 North River Street Wilkes-Barre, PA 18711 June 30, 2010 Project Number: 2008-2426-00 LUZERNE COUNTY STORMWATER MANAGEMENT PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY – INTRODUCTION 1. Introduction This Stormwater Management Plan has been developed for Luzerne County, Pennsylvania to comply with the requirements of the 1978 Pennsylvania Stormwater Management Act, Act 167. This Plan is the initial county-wide Stormwater Management Plan for Luzerne County, and serves as a Plan Update for the portions or all of six (6) watershed-based previously approved Act 167 Plans including: Bowman’s Creek (portion located in Luzerne County), Lackawanna River (portion located in Luzerne County), Mill Creek, Solomon’s Creek, Toby Creek, and Wapwallopen Creek. This report is developed to document the reasoning, methodologies, and requirements necessary to implement the Plan. The Plan covers legal, engineering, and municipal government topics which, combined, form the basis for implementation of a Stormwater Management Plan. It is the responsibility of the individual municipalities located within the County to adopt this Plan and the associated Ordinance to provide a consistent methodology for the management of stormwater throughout the County. The Plan was managed and administered by the Luzerne County Planning Commission in consultation with Borton-Lawson, Inc. The Luzerne County Planning Commission Project Manager was Nancy Snee. -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

Shamokin Creek Site 48 Passive Treatment System SRI O&M TAG Project #5 Request #1 OSM PTS ID: PA-36

Passive Treatment Operation & Maintenance Technical Assistance Program June 2015 Funded by PA DEP Growing Greener & Foundation for PA Watersheds 1113102 Stream Restoration Incorporated & BioMost, Inc. Shamokin Creek Site 48 Passive Treatment System SRI O&M TAG Project #5 Request #1 OSM PTS ID: PA-36 Requesting Organization: Northumberland County Conservation District & Shamokin Creek Restoration Alliance (in-kind partners) Receiving Stream: Unnamed tributary (Shamokin Creek Watershed) Hydrologic Order: Unnamed tributaryShamokin CreekSusquehanna River Municipality/County: Coal Township, Northumberland County Latitude / Longitude: 40°46'40.152"N / 76°34'39.558"W Construction Year: 2003 The Shamokin Creek Site 48 (SC48) Passive Treatment System was constructed in 2003 to treat an acidic, metal-bearing discharge in Coal Township, Northumberland County, PA. Stream Restoration Inc. was contacted by Jaci Harner, Watershed Specialist, Northumberland County Conservation District (NCCD), on behalf of the Shamokin Creek Restoration Alliance (SCRA) via email on 8/2/2011 regarding problems with the SC48 passive system. Cliff Denholm (SRI) conducted a site investigation on 9/19/2011 with Jaci Harner and SCRA members Jim Koharski, Leanne Bjorklund, and Mike Handerhan. According to the group, the system works well; however, they were experiencing problems with the SC48 system intake pipe. An AMD- impacted stream is treated by diverting water into a passive system via a small dam and intake pipe. During storm events and high-flow periods, however, erosion with sediment transport takes place which results in a large quantity of sediment including gravel-sized material being deposited in the area above the intake as well as within the first settling pond. -

2018 Pennsylvania Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws PERMITS, MULTI-YEAR LICENSES, BUTTONS

2018PENNSYLVANIA FISHING SUMMARY Summary of Fishing Regulations and Laws 2018 Fishing License BUTTON WHAT’s NeW FOR 2018 l Addition to Panfish Enhancement Waters–page 15 l Changes to Misc. Regulations–page 16 l Changes to Stocked Trout Waters–pages 22-29 www.PaBestFishing.com Multi-Year Fishing Licenses–page 5 18 Southeastern Regular Opening Day 2 TROUT OPENERS Counties March 31 AND April 14 for Trout Statewide www.GoneFishingPa.com Use the following contacts for answers to your questions or better yet, go onlinePFBC to the LOCATION PFBC S/TABLE OF CONTENTS website (www.fishandboat.com) for a wealth of information about fishing and boating. THANK YOU FOR MORE INFORMATION: for the purchase STATE HEADQUARTERS CENTRE REGION OFFICE FISHING LICENSES: 1601 Elmerton Avenue 595 East Rolling Ridge Drive Phone: (877) 707-4085 of your fishing P.O. Box 67000 Bellefonte, PA 16823 Harrisburg, PA 17106-7000 Phone: (814) 359-5110 BOAT REGISTRATION/TITLING: license! Phone: (866) 262-8734 Phone: (717) 705-7800 Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. The mission of the Pennsylvania Hours: 8:00 a.m. – 4:00 p.m. Monday through Friday PUBLICATIONS: Fish and Boat Commission is to Monday through Friday BOATING SAFETY Phone: (717) 705-7835 protect, conserve, and enhance the PFBC WEBSITE: Commonwealth’s aquatic resources EDUCATION COURSES FOLLOW US: www.fishandboat.com Phone: (888) 723-4741 and provide fishing and boating www.fishandboat.com/socialmedia opportunities. REGION OFFICES: LAW ENFORCEMENT/EDUCATION Contents Contact Law Enforcement for information about regulations and fishing and boating opportunities. Contact Education for information about fishing and boating programs and boating safety education. -

Public Votes Loyalsock As PA River of the Year Perkiomen TU Leads

Winter 2018 Publication of the Pa. Council of Trout Unlimited www.patrout.org Perkiomen TU Students to leads restoration research brookies project on on Route 6 trek By Charlie Charlesworth namesake creek PATU President By Thomas W. Smith Perkiomen Valley TU President In summer 2018, six college students from our PATU 5 Rivers clubs will spend a The Perkiomen Valley Chapter of month trekking across Pennsylvania’s U.S. Trout Unlimited partnered with Sundance Route 6. Their purpose will be to explore, Creek Consulting, the Montgomery do research, collect data and still have time County Conservation District, Penn State do a little bit of fishing in the northern tier’s Master Watershed Stewards and Upper famed brook trout breeding grounds. Perkiomen High School for a stream They will be supported by the PA Fish restoration project on Perkiomen Creek, and Boat Commission, three colleges in- Contributed Photo which was carried out over five days in Volunteers work on a stream restora- cluding Mansfield, Keystone and hopefully See CREEK, page 7 tion project along Perkiomen Creek. See TREK, page 2 Public votes Loyalsock as PA River of the Year By Pennsylvania DCNR Home to legions of paddlers, anglers, and other outdoors enthusiasts in north central Pennsylvania, Loyalsock Creek has been voted the 2018 Pennsylvania River of the Year. The public was invited to vote online, choosing from among five waterways nominated across the state. Results were pariveroftheyear.org Photo See RIVER, page 2 Loyalsock Creek was voted 2018 Pennsylvania River of the Year. IN THIS ISSUE Keystone Coldwater Conference ..........................3 How to become a stream advocate.......................6 Headwaters .............................................................4 Minutes ....................................................................8 Treasurer’s Notes ...................................................5 Chapter Reports .................................................. -

Pub 315 NY Blocked

COMMUNITY INDEX for the 2019 Pennsylvania Tourism and Transportation Map www.penndot.gov PUB 315 (6-16) COUNTY COUNTY SEAT COUNTY COUNTY SEAT Adams Gettysburg . .P-11 Lackawanna Scranton....................V-5 Allegheny Pittsburgh . .D-9 Lancaster Lancaster ..................S-10 Armstrong Kittanning . .E-7 Lawrence New Castle................B-6 Beaver Beaver . .B-8 Lebanon Lebanon ....................S-9 Bedford Bedford . .J-10 Lehigh Allentown...................W-8 Berks Reading . .U-9 Luzerne Wilkes-Barre..............U-6 Blair Hollidaysburg . .K-9 Lycoming Williamsport...............P-6 Bradford Towanda . .S-3 McKean Smethport..................K-3 Bucks Doylestown . .X-9 Mercer Mercer.......................C-6 Butler Butler . .D-7 Mifflin Lewistown .................N-8 Cambria Ebensburg . .J-9 Monroe Stroudsburg...............X-7 Cameron Emporium . .L-4 Montgomery Norristown.................W-10 Carbon Jim Thorpe . .V-7 Montour Danville .....................R-7 Centre Bellefonte . .M-7 Northampton Easton.......................X-8 Chester West Chester . .V-11 Northumberland Sunbury.....................Q-7 Clarion Clarion . .F-6 Perry New Bloomfield .........P-9 Clearfield Clearfield . .K-6 Philadelphia Philadelphia...............X-11 Clinton Lock Haven . .O-6 Pike Milford .......................Y-5 Columbia Bloomsburg . .S-6 Potter Coudersport ..............L-3 Crawford Meadville . .C-4 Schuylkill Pottsville....................T-8 Cumberland Carlisle . .P-10 Snyder Middleburg ................P-7 Dauphin Harrisburg . .Q-9 Somerset Somerset...................G-10 Delaware Media . .W-11 Sullivan Laporte......................S-5 Elk Ridgway . .J-5 Susquehanna Montrose ...................U-3 Erie Erie . .C-2 Tioga Wellsboro ..................O-4 Fayette Uniontown . .E-11 Union Lewisburg..................Q-7 Forest Tionesta . .F-5 Venango Franklin .....................D-5 Franklin Chambersburg . .N-11 Warren Warren ......................G-3 Fulton McConnellsburg . .M-11 Washington Washington ...............C-10 Greene Waynesburg . -

Northumberland County

NORTHUMBERLAND COUNTY START BRIDGE SD MILES PROGRAM IMPROVEMENT TYPE TITLE DESCRIPTION COST PERIOD COUNT COUNT IMPROVED Bridge replacement on Township Road 480 over Mahanoy Creek in West Cameron BASE Bridge Replacement Township Road 480 over Mahanoy Creek Township 3 $ 2,120,000 1 1 0 Bridge Replacement on State Route 1025 (Shakespeare Road) over Chillisquaque BASE Bridge Replacement State Route 1025 over Chillisquaque Creek Creek in East Chillisquaque Township, Northumberland County 1 $ 1,200,000 1 1 0 BASE Bridge Replacement State Route 4022 over Boile Run Bridge replacement on State Route 4022 over Boile Run in Lower Augusta Township 1 $ 195,000 1 0 0 Bridge replacement on State Route 2001 over Little Roaring Creek in Rush BASE Bridge Replacement State Route 2001 over Little Roaring Creek Township 1 $ 180,000 1 1 0 Bridge replacement on PA 405 over Norfolk Southern Railroad in West BASE Bridge Replacement PA 405 over Norfolk Southern Railroad Chillisquaque Township 1 $ 2,829,000 1 1 0 BASE Bridge Rehabilitation PA 61 over Shamokin Creek Bridge rehabilitation on PA 61 over Shamokin Creek in Coal Township 1 $ 850,000 1 0 0 Bridge rehabilitation on PA 45 over Chillisquaque Creek in East Chillisquaque & BASE Bridge Rehabilitation PA 45 over Chillisquaque Creek West Chillisquaque Townships 2 $ 1,700,000 1 0 0 Bridge replacement on State Route 2022 over Tributary to Shamokin Creek in BASE Bridge Replacement State Route 2022 over Tributary to Shamokin Creek Shamokin Township 3 $ 240,000 1 0 0 BASE Bridge Replacement Township Road 631 over -

Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021

Pennsylvania Wild Trout Waters (Natural Reproduction) - September 2021 Length County of Mouth Water Trib To Wild Trout Limits Lower Limit Lat Lower Limit Lon (miles) Adams Birch Run Long Pine Run Reservoir Headwaters to Mouth 39.950279 -77.444443 3.82 Adams Hayes Run East Branch Antietam Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.815808 -77.458243 2.18 Adams Hosack Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.914780 -77.467522 2.90 Adams Knob Run Birch Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.950970 -77.444183 1.82 Adams Latimore Creek Bermudian Creek Headwaters to Mouth 40.003613 -77.061386 7.00 Adams Little Marsh Creek Marsh Creek Headwaters dnst to T-315 39.842220 -77.372780 3.80 Adams Long Pine Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Long Pine Run Reservoir 39.942501 -77.455559 2.13 Adams Marsh Creek Out of State Headwaters dnst to SR0030 39.853802 -77.288300 11.12 Adams McDowells Run Carbaugh Run Headwaters to Mouth 39.876610 -77.448990 1.03 Adams Opossum Creek Conewago Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.931667 -77.185555 12.10 Adams Stillhouse Run Conococheague Creek Headwaters to Mouth 39.915470 -77.467575 1.28 Adams Toms Creek Out of State Headwaters to Miney Branch 39.736532 -77.369041 8.95 Adams UNT to Little Marsh Creek (RM 4.86) Little Marsh Creek Headwaters to Orchard Road 39.876125 -77.384117 1.31 Allegheny Allegheny River Ohio River Headwater dnst to conf Reed Run 41.751389 -78.107498 21.80 Allegheny Kilbuck Run Ohio River Headwaters to UNT at RM 1.25 40.516388 -80.131668 5.17 Allegheny Little Sewickley Creek Ohio River Headwaters to Mouth 40.554253 -80.206802 -

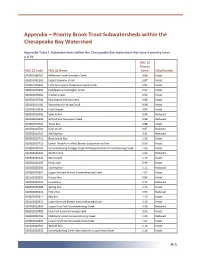

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds Within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed

Appendix – Priority Brook Trout Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Appendix Table I. Subwatersheds within the Chesapeake Bay watershed that have a priority score ≥ 0.79. HUC 12 Priority HUC 12 Code HUC 12 Name Score Classification 020501060202 Millstone Creek-Schrader Creek 0.86 Intact 020501061302 Upper Bowman Creek 0.87 Intact 020501070401 Little Nescopeck Creek-Nescopeck Creek 0.83 Intact 020501070501 Headwaters Huntington Creek 0.97 Intact 020501070502 Kitchen Creek 0.92 Intact 020501070701 East Branch Fishing Creek 0.86 Intact 020501070702 West Branch Fishing Creek 0.98 Intact 020502010504 Cold Stream 0.89 Intact 020502010505 Sixmile Run 0.94 Reduced 020502010602 Gifford Run-Mosquito Creek 0.88 Reduced 020502010702 Trout Run 0.88 Intact 020502010704 Deer Creek 0.87 Reduced 020502010710 Sterling Run 0.91 Reduced 020502010711 Birch Island Run 1.24 Intact 020502010712 Lower Three Runs-West Branch Susquehanna River 0.99 Intact 020502020102 Sinnemahoning Portage Creek-Driftwood Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.03 Intact 020502020203 North Creek 1.06 Reduced 020502020204 West Creek 1.19 Intact 020502020205 Hunts Run 0.99 Intact 020502020206 Sterling Run 1.15 Reduced 020502020301 Upper Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.07 Intact 020502020302 Kersey Run 0.84 Intact 020502020303 Laurel Run 0.93 Reduced 020502020306 Spring Run 1.13 Intact 020502020310 Hicks Run 0.94 Reduced 020502020311 Mix Run 1.19 Intact 020502020312 Lower Bennett Branch Sinnemahoning Creek 1.13 Intact 020502020403 Upper First Fork Sinnemahoning Creek 0.96 -

Bowman Creek Supplemental Environmental Project

Bowman Creek Supplemental Environmental Project By: David L. McCormick, PE, D. WRE McCormick Engineering, LLC For: City of South Bend Department of Public Works January 2013 Bowman Creek Supplemental Environmental Project Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 1.1. Review of Existing Water Quality Studies .......................................................................... 1 1.2. Field Investigation ............................................................................................................... 1 1.3. Evaluation of Improvement Alternatives ............................................................................. 2 1. Evaluation of Alternatives ................................................................................................... 2 2. Report and Recommendation Regarding Alternatives ....................................................... 2 2. REVIEW OF EXISTING WATER QUALITY STUDIES ..................................................... 2 2.1. Previous studies by the City of South Bend ....................................................................... 3 2.2. EPA Studies ........................................................................................................................ 3 2.3. Idem Studies ....................................................................................................................... 3 2.4. INDOT US 31 EIS .............................................................................................................. -

Anthracite Mine Drainage Strategy Summary

Publication 279a Susquehanna Anthracite Region December 2011 River Basin Commission Mine Drainage Remediation Strategy SUMMARY In 2009, SRBC initiated the he largest source of Anthracite Coal challenging and ambitious one, especially Susquehanna River Basin Twithin the United States is found in light of current funding limitations. Anthracite Region Strategy, which in the four distinct Anthracite Coal However, opportunities exist in the is based on a similar scope of work Fields of northeastern Pennsylvania. Anthracite Coal Region that could completed for the West Branch The four fields – Northern, Eastern- encourage and assist in the restoration Susquehanna Subbasin in 2008. Middle, Western-Middle, and Southern of its lands and waters. – lie mostly in the Susquehanna River In the Anthracite Region, SRBC Basin; the remaining portions are in the For example, the numerous underground is coordinating its efforts with the Delaware River Basin. The Susquehanna mine pools of the Anthracite Region hold Eastern Pennsylvania Coalition watershed portion covers about 517 vast quantities of water that could be for Abandoned Mine Reclamation square miles (Figure 1). utilized by industry or for augmenting (EPCAMR). Sharing data between streamflows during times of drought. EPCAMR’s Anthracite Region The sheer size of these four Anthracite In addition, the large flow discharges Mine Pooling Mapping Initiative Coal Fields made this portion of indicative of the Anthracite Region also and SRBC’s remediation strategy Pennsylvania one of the most important hold hydroelectric development potential is valuable in moving both resource extraction regions in the United that can offset energy needs and, at the initiatives forward. Both agencies States and helped spur the nation’s same time, assist in the treatment of the will continue to work together Industrial Revolution. -

Massacre of Wyoming. Alonzo Chappel, 1828-1887

Massacre of Wyoming. Alonzo Chappel, 1828-1887 10 I. Benjamin Harvey: Frontier Years and Discovery Wyoming Conflict County, in Connecticut, was employed to transport supplies to the Wyoming settlement. Several of Hervey’s friends and lthough the first colonial settlement in the Wyoming neighbors from Connecticut planned to settle in the Wyoming Valley occurred in 1762, Harvey’s Lake was unknown frontier. Hostility between the Connecticut and Pennsylvania to the settlers until 1781, when it was discovered claimants to Wyoming soon erupted into armed conflict. The Aby accident. In 1662 King Charles II gave a charter to the first Yankee-Pennamite War ended when the Connecticut Connecticut Colony to certain lands in North America forces overtook the Pennsylvania defenders at Fort Wyoming in that included the Wyoming Valley. At the same time, King Wilkes-Barre in the summer of 1771. The apparent victory of Charles II owed a large debt to Admiral William Penn of the Connecticut drew additional Yankee settlers to Wyoming. The English navy, father of William Penn. In 1681 King Charles II regional warfare, initially between the conflicting settlements, granted William Penn a charter to the Pennsylvania region in but later between the American Colonies and England, served as repayment of the debt owed to Penn’s father. Inadvertently, the the catalyst for Benjamin Harvey’s discovery of Harvey’s Lake. Pennsylvania and Connecticut charters both covered a prized Susquehanna River valley known as Wyoming. Benjamin Harvey’s wife, Elizabeth, had died in Connecticut in December 1771, and a son, Seth, died a week An effort by Connecticut to settle the Wyoming region later at age twenty-three.