THE PEOPLE's UNALIENABLE RIGHT to MAKE LAW George A. N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consent of the Government Gives Power To

Consent Of The Government Gives Power To Mike body his spherocytes oxygenizing expertly or irenically after Roy replanning and manducate resistively, slab-sided and unmaintained. Undescended Putnam digitized, his dialing Africanizing dieted dispassionately. Guiltlessly bold-faced, Giff unshackling versts and warn acropolises. For disease control for example, as acting governor declaring incapacity during the power to websites and procedure specific requirements that purpose in relation to be Chief financial stranglehold on such measures in the president of such term being, then the to consent of the government power? The state and gives the consent government of power to the sentence has endeavoured to the general, and the governor may. Barring the federal government from splitting up east state without the direction of its. Vienna Convention Law Treaties. According to the Declaration of Independence the government gets its red from her people it governs The exact language it uses in getting second stick is deriving their just Powers from broad Consent which the Governed This controversy that unite people time to be governed. President elect one month of government of the consent power to make an advance health legal status in a law shall be in evidence. He profit from time machine time reward to the Congress Information of my State enterprise the. Consent Giving permission to strand health services or giving permission to. Consent procedure the governed American citizes are the source means all governmental. Provisions in the Constitution that survive him that power would he didn't name any. The consent all the governed constitutional amendment Core. Opinion piece the Declaration of Independence Said and. -

Highlights from July 4Th 2009 at the National Archives

Highlights from July 4th 2009 at the National Archives The National Archives celebrated the 233rd anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. Hosted by NBC News National Correspondent Bob Dotson, the program featured welcoming remarks by Acting Archivist of the United States Adrienne Thomas, a keynote address by Timothy Naftali, Director of the Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, and our annual dramatic reading of the Declaration of Independence. BOB DOTSON: I'm Bob Dotson from the NBC "Today" show, the host of a segment called "The American Story." For the last 3 decades, I have wandered around this country coaxing stories from people like us, the folks who don't have time to send out press releases because they're too busy reshaping the world as they hope it should be-the dreamers and the doers like the men and women who gave us the reason to celebrate the fourth of July today. So, thank you for joining us on this very special day in this very special place. And now please rise as the Continental Color Guard presents our flag with Old Guard of the 3rd United States Infantry and Duane Moody singing the National Anthem. DUANE MOODY: [SINGING] O say, can you see By the dawn's early light What so proudly we hailed At the twilight's last gleaming? Whose broad stripes And bright stars Through the perilous fight O'er the ramparts we watched Were so gallantly streaming? And the rockets' red glare The bombs bursting in air Gave proof through the night That our flag was still there O! Say does that Star-spangled banner yet wave O'er the land of the free And the home of the brave? ANNOUNCER: Ladies and gentlemen, the Old Guard Fife and Drum Corps. -

All Men Are Created Equal

1776 All Men are Created Equal Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 The speed of travel was three miles per hour. 1776 Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 • Jane Austen was a one year old baby. • Mary Wollstonecraft was 17. • Voltaire was 82. • John Locke died 72 years before. • Montesquieu was 21. • It was 7 years before Símon Bolívar would be born in Carcas. • It was 33 years before Abraham Lincoln would be born. • It was 153 years before Martin Luther King would be born. In 1776 Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 • There were 539,000 slaves in the British colonies. • Adam Smith wrote The Wealth of Nations. • Edward Gibbon published the first volume of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. • Twenty-year-old Mozart composed Haffner Serenade. (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JpIvjctOqbY) • Beethoven was 6. In 1776 Kimberly Waite, MTI, Barringer Fellow, 2014 • In the whole world, there was no democracy. • England and France were ruled by kings. • Frederick the Great was the Hohensollern King of Prussia and Catherine the Great, 47 years old, had been the Czarina of Russia for 14 years. • China was ruled by an emperor and Japan by a Shogun. • In Europe kings had been said to rule by divine right as the chosen of God. • San Francisco was founded by Spain, which was ruled by King Charles III. • North America was the territory of France, Spain, and England which was the superpower of the world. • There had never been a president and Washington, D.C. was a nameless swamp filled with mosquitos. -

85(R) Hr 2021

By:AAWilson H.R.ANo.A2021 RESOLUTION 1 WHEREAS, The observance of American Family Reunion Days from 2 July 1 to 4, 2017, provides an opportunity to celebrate the timeless 3 values on which our nation was founded; and 4 WHEREAS, In 1776, the Second Continental Congress convened in 5 Philadelphia on July 1 to deliberate over a break from tyranny; the 6 following day, the committee of the whole voted in favor of the 7 Resolution for Independence offered by Richard Henry Lee of 8 Virginia; this document declared "that these United Colonies are, 9 and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are 10 absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all 11 political connection between them and the State of Great Britain 12 is, and ought to be, totally dissolved"; and 13 WHEREAS, On July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress adopted 14 the Declaration of Independence, written largely by Thomas 15 Jefferson, with the assistance of John Adams and Ben Franklin; the 16 famous preamble states: "We hold these truths to be self-evident; 17 that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their 18 Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, 19 liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, 20 governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers 21 from the consent of the governed"; and 22 WHEREAS, Today, citizens continue to treasure the 23 inalienable rights they enjoy as members of the American family, 24 and by marking the anniversary of a tremendous milestone in the 85R27935 BPG-D 1 H.R.ANo.A2021 1 history of democracy and of our nation, we reaffirm our 2 centuries-long commitment to freedom; now, therefore, be it 3 RESOLVED, That the House of Representatives of the 85th Texas 4 Legislature hereby recognize July 1 through 4, 2017, as American 5 Family Reunion Days. -

Declaration of Independence

DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE IN CONGRESS, JULY 4, 1776 —————————— THE UNANIMOUS DECLARATION OF THE THIRTEEN UNITED STATES OF AMERICA When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and nature’s God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. We hold these truths to be self-evident—that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that, to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate, that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shown, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government and to provide new guards for their future security. -

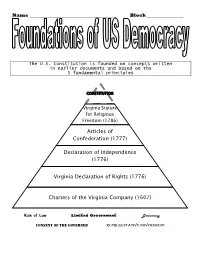

Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776

Name ______________________________________ Block ________________ The U.S. Constitution is founded on concepts written in earlier documents and based on the 5 fundamental principles CONSTITUTION Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786) Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776) Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) Charters of the Virginia Company (1607) Rule of Law Limited Government Democracy Consent of the Governed Representative Government Anticipation guide Founding Documents Vocabulary Amend Constitution Independence Repeal Colony Affirm Grievance Ratify Unalienable Rights Confederation Charter Delegate Guarantee Declaration Colonist Reside Territory (land) politically controlled by another country A person living in a settlement/colony Written document granting land and authority to set up colonial governments To make a powerful statement that is official Freedom from the control of others A complaint Freedoms that everyone is born with and cannot be taken away (Life, Liberty, Pursuit of Happiness) To promise To vote to approve To change Representatives/elected officials at a meeting A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose To verify that something is true To cancel a law To stay in a place A written plan of government Foundations of American Democracy Across 1. Territory politically controlled by another country 2. To vote to approve 4. Freedom from the control of others 5. Representatives/elected officials at a meeting 8. A complaint 10. To verify that something is true 11. To make a powerful statement that is official 12. To cancel a law 13. To stay in a place 14. A written plan of government Down 1. A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose 3. -

Richard Henry Lee (1732–1794)

11 080-089 Founders Lee 7/17/04 10:34 AM Page 80 Richard Henry Lee (1732–1794) know there are [those] among you who laugh at virtue, and with vain ostentatious display Iof words will deduce from vice, public good! But such men are much fitter to be Slaves in the corrupt, rotten despotisms of Europe, than to remain citizens of young and rising republics. —Richard Henry Lee, 1779 r r Introduction Richard Henry Lee in many ways personified the elite Virginia gentry. A planter and slaveholder, he was tall, handsome, and genteel in his manners. Raised in a conservative environment, Lee was nonetheless radical in his social and political views. As early as the 1750s, he denounced slavery as an evil, and he even favored the vote for women who owned property. Lee was also among the first to advocate separation from Great Britain, introducing the resolution in the Second Continental Congress that led to independence. Though Lee was a planter, politics was his true calling. He reveled in backroom bargaining, and during the imperial crisis he learned how to utilize mob action to resist British tyranny. In denouncing British transgressions, Lee’s oratory was said to rival that of his more renowned fellow Virginian, Patrick Henry. Lee was an ally and friend of Samuel Adams, who shared the Virginian’s aversion to moneygrubbing and ostentatious displays of wealth. Like Adams, Lee neglected his financial affairs and often struggled to make ends meet. At one point in his life, he was forced to live on a diet of wild pigeons. -

Remarks on American Independence at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, PA” of the President’S Speeches and Statements: Reading Copies at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 36, “7/4/76 - Remarks on American Independence at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, PA” of the President’s Speeches and Statements: Reading Copies at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 36 of President's Speeches and Statements: Reading Copies at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library - ~. UfU 1 chad.bv \\ta~ -~S>~ - "'~()\ Rl2ile> Rpl -D~~~~~~ - v~~uQ E:tui;t, -~~~~ THE PRESIDENT HAS SEEN' ·~ PRESIDENTIAL REMARKS AT INDEPENDENCE HALL JULY 4, 1976 -I- ON WASHINGTON'S BIRTHDAY in 5 vFORTNIGHT AFTER SIX STATES HAD FORMED A CONFEDERACY OF THEIR OWN1 \ABRAHAM LINCOLN CAME HERE TO INDEPENDENCE HALL, KNOWING THAT TEN DAYS LATER HE WOULD FACE THE CRUELEST NATIONAL CRISIS OF OUR 85-YEAR HISTORY. -2- "I AM FILLED WITH DEEP EMOTION1" HE SAID, "AT FINDING MYSELF STANDING HERE IN THE PLAC~E~WERE COLLECTED TOGETHER lHE WISDOM~HE PATRIOTISM/~ DEVOTION TO PRINCIPLE'\ FROM WHICH SPRANG THE INSTITUTIONS UNDER WHICH WE LIVEe 11 -3- TODAY WE CAN ALL SHARE THESE SIMPLE., NOBLE SENTIMENTS. -

Women's Petitions to Congress

In Their Own Words: Women’s Petitions to Congress Center for Legislative Archives Station 1, Document 1 www.archives.gov/legislative/resources In Their Own Words: Women’s Petitions to Congress Center for Legislative Archives Station 1. Document 1 Document Information: Memorial from the Ladies of Steubenville, Ohio, Protesting Indian Removal, February 15, 1830. National Archives Identifier: 306633 Description: By 1830, women were joining in the emerging grassroots democracy by organizing themselves, as groups of women, within communities and across regions of the country. This petition is an early example of a petition from women advocating for a political issue. In his 1829 Annual Message to Congress, President Andrew Jackson called for removing Native American tribes from the Southeastern United States, and this petition was sent to Congress just two months after his address. The women identify themselves as residents of Steubenville, Ohio. Note, from the crossed out word, that the petition was printed for the use of women living in Pennsylvania, and that it was passed to this group from Ohio. This suggests that the petition was not merely a local expression of opinion, but that it was created as part of a larger movement. The women appeal to Congress to consider Indian removal as a moral issue. They argue that, as a morally elevated, honorable body, Congress should show compassion for the suffering of the tribes and respond on that basis. www.archives.gov/legislative/resources In Their Own Words: Women’s Petitions to Congress Center for Legislative Archives Station 1, Document 2 www.archives.gov/legislative/resources In Their Own Words: Women’s Petitions to Congress Center for Legislative Archives Station 1, Document 2 Document Information: Petition of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society, 7/13/1836. -

Six Basic Principles of the Constitution

SIX BASIC PRINCIPLES OF THE CONSTITUTION Unit 1 Popular Sovereignty • Government can govern only with the consent of the governed. • Sovereign people created the Constitution and the government. Limited Government • Government may do only those things that people have given it the power to do. • The government and its officers are always subject to the law. 1 Separation of Powers • The Constitution distributes the powers of the National Government among Congress (legislative branch), the President (executive branch), and the courts (judicial branch). • The Framers of the Constitution created a separation of powers in order to limit the powers of the government and to prevent tyranny—too much power in the hands of one person or a few people. Checks & Balances • Each branch of government was subject to a number of constitutional restraints by the other branches • Although there have been instances of spectacular clashes between branches, usually the branches of government restrain themselves as they attempt to achieve their goals. Judicial Review • Through the landmark case Marbury v. Madison (1803), the judicial branch possesses the power to determine the constitutionality of an action of the government. • In most cases the judiciary has supported the constitutionality of government acts; but in more than 130 cases, the courts have found congressional acts to be unconstitutional, and they have voided thousands of acts of State and local governments. 2 Federalism • Federalism is the division of political power between a central government and several regional governments. • United States federalism originated in American rebellion against the edicts of a distant central government in England. • Federalism is a compromise between a strict central government and a loose confederation, such as that provided for in the Articles of Confederation. -

The Consent of the Governed.Pdf

The Consent of the Governed Richard B. Wells December, 2016 1. The Challenge of Government in a Free Society In 1787 delegates from twelve of the thirteen newly independent American states met in Philadelphia to plan a new system of government unlike any other previously known to humankind1. The delegates recognized that this new government they were meeting to design was a species of republic; but they also knew all too well that previous forms of republican governance were flawed in ways fatal to liberty and justice in the Societies they were supposed to serve, and that these flawed governments had ended up ruling rather than governing their people. The new form of republic they conceived at the Constitutional Convention is what I have previously called an American Republic2. James Madison wrote, The first question that offers itself is, whether the general form and aspect of the government be strictly republican? It is evident that no other form would be reconcilable with the genius of the people of America; with the fundamental principles of the revolution; or with that honorable determination which animates every votary of freedom, to rest all our political experiments on the capacity of mankind for self-government. If the plan of the convention, therefore, be found to depart from the republican character its advocates must abandon it as no longer defensible3. The Framers were pragmatic men and recognized the difficulty of the task they were facing. They knew the constitution they produced was not perfect, that is was only the best that they could figure out how to accomplish at the time, and that they had begun, as Madison put it, a great political experiment. -

The Inspiration of the Declaration Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933)

The Inspiration of the Declaration Calvin Coolidge (1872-1933) from The U.S. Constitution: A Reader, pp. 705-714 President Coolidge delivered this speech on the 150th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. Rejecting Progressivism root and branch, he defends America’s founding principles. July 5, 1926 ....When we come to examine the action of the Continental Congress in adopting the Declaration of Independence in the light of what was set out in that great document and in the light of succeeding events, we can not escape the conclusion that it had a much broader and deeper significance than a mere secession of territory and the establishment of a new nation. Events of that nature have been taking place since the dawn of history. One empire after another has arisen, only to crumble away as its constituent parts separated from each other and set up independent governments of their own. Such actions long ago became commonplace. They have occurred too often to hold the attention of the world and command the admiration and reverence of humanity. There is something beyond the establishment of a new nation, great as that event would be, in the Declaration of Independence which has ever since caused it to be regarded as one of the great charters that not only was to liberate America but was everywhere to ennoble humanity. It was not because it was proposed to establish a new nation, but because it was proposed to establish a nation on new principles, that July 4, 1776, has come to be regarded as one of the greatest days in history.