Learning Movement Theory Through Online Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1

DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF WEST GEORGIA Spring 2017 Advanced Sociological Theory SOCI 6305, Section 1 Tuesday, 5:30-8:00 PM, Pafford 306 Dr. Emily McKendry-Smith Office: Pafford 319 Office hours: Mon. 1-2, 3:30-4:30, Tues. 1-5, and Weds. 11-2, 3:30-4:30, or by appointment Email: [email protected] Do NOT email me using CourseDen! “Social theory is a basic survival skill. This may surprise those who believe it to be a special activity of experts of a certain kind. True, there are professional social theorists, usually academics. But this fact does not exclude my belief that social theory is something done necessarily, and often well, by people with no particular professional credential. When it is done well, by whomever, it can be a source of uncommon pleasure.” – Charles Lemert, 1993 Course Information and Goals: This course provides a foundation in the key components of classical and contemporary social theory, as used by academic sociologists. This course is a seminar, not a lecture series. Unlike undergraduate courses, the purpose of this course is not to memorize a set of “facts,” but to develop your critical thinking skills by using them to evaluate theory. Instead, this course will consist of discussions centered on key questions from the readings. This course format requires that you be active participants. If discussion does not emerge spontaneously, I will prompt it by asking questions and pushing for your point of view. (That said, some of these theories can be difficult to understand; I will help you with this and we will work together in class to uncover the readings’ main points). -

Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology Eddie Hartmann, Potsdam University

DOI: 10.4119/UNIBI/ijcv.623 IJCV: Vol. 11/2017 Violence: Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology Eddie Hartmann, Potsdam University Vol. 11/2017 The IJCV provides a forum for scientific exchange and public dissemination of up-to-date scientific knowledge on conflict and violence. The IJCV is independent, peer reviewed, open access, and included in the Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) as well as other relevant databases (e.g., SCOPUS, EBSCO, ProQuest, DNB). The topics on which we concentrate—conflict and violence—have always been central to various disciplines. Con- sequently, the journal encompasses contributions from a wide range of disciplines, including criminology, econom- ics, education, ethnology, history, political science, psychology, social anthropology, sociology, the study of reli- gions, and urban studies. All articles are gathered in yearly volumes, identified by a DOI with article-wise pagination. For more information please visit www.ijcv.org Author Information: Eddie Hartmann, Potsdam University [email protected] Suggested Citation: APA: Hartmann, E. (2017). Violence: Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 11, 1-9. doi: 10.4119/UNIBI/ijcv.623 Harvard: Hartmann, Eddie. 2017. Violence: Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology. International Journal of Conflict and Violence 11:1-9. doi: 10.4119/UNIBI/ijcv.623 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives License. ISSN: 1864–1385 IJCV: Vol. 11/2017 Hartmann: Violence: Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology 1 Violence: Constructing an Emerging Field of Sociology Eddie Hartmann, Potsdam University @ Recent research in the social sciences has explicitly addressed the challenge of bringing violence back into the center of attention. -

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology

SOC 103: Sociological Theory Tufts University Department of Sociology Image courtesy of Owl Turd Comix: http://shencomix.com *Syllabus updated 1-20-2018 When: Mondays & Wednesdays, 3:00-4:15 Where: 312 Anderson Hall Instructor: Assistant Professor Freeden Blume Oeur Grader: Laura Adler, Sociology Ph.D. student, Harvard University Email: [email protected] Phone: 617.627.0554 Office: 118 Eaton Hall Website: http://sites.tufts.edu/freedenblumeoeur/ Office Hours: Drop-in Tuesdays 2-3:30 & Thursdays 10-11:30; and by appointment WELCOME The Greek root of theory is theorein, or “to look at.” Sociological theories are therefore visions, or ways of seeing and interpreting the social world. Some lenses have a wide aperture and seek to explain macro level social developments and historical change. The “searchlight” (to borrow Alfred Whitehead’s term) for other theories could be narrower, but their beams may offer greater clarity for things within their view. All theories have blind spots. This course introduces you to an array of visions on issues of enduring importance for sociology, such as alienation and emancipation, solidarity and integration, domination and violence, epistemology, secularization and rationalization, and social transformation and social reproduction. This course will highlight important 1 theories that have not been part of the sociological “canon,” while also introducing you to more classical theories. Mixed in are a few poignant case studies. We’ll also discuss the (captivating, overlooked, even misguided) origins of modern sociology. I hope you enjoy engaging with sociological theory as much as I do. I think it’s the sweetest thing. We’ll discuss why at the first class. -

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations

Sociological Theories of Deviance: Definitions & Considerations NCSS Strands: Individuals, Groups, and Institutions Time, Continuity, and Change Grade level: 9-12 Class periods needed: 1.5- 50 minute periods Purpose, Background, and Context Sociologists seek to understand how and why deviance occurs within a society. They do this by developing theories that explain factors impacting deviance on a wide scale such as social frustrations, socialization, social learning, and the impact of labeling. Four main theories have developed in the last 50 years. Anomie: Deviance is caused by anomie, or the feeling that society’s goals or the means to achieve them are closed to the person Control: Deviance exists because of improper socialization, which results in a lack of self-control for the person Differential association: People learn deviance from associating with others who act in deviant ways Labeling: Deviant behavior depends on who is defining it, and the people in our society who define deviance are usually those in positions of power Students will participate in a “jigsaw” where they will become knowledgeable in one theory and then share their knowledge with the rest of the class. After all theories have been presented, the class will use the theories to explain an historic example of socially deviant behavior: Zoot Suit Riots. Objectives & Student Outcomes Students will: Be able to define the concepts of social norms and deviance 1 Brainstorm behaviors that fit along a continuum from informal to formal deviance Learn four sociological theories of deviance by reading, listening, constructing hypotheticals, and questioning classmates Apply theories of deviance to Zoot Suit Riots that occurred in the 1943 Examine the role of social norms for individuals, groups, and institutions and how they are reinforced to maintain a order within a society; examine disorder/deviance within a society (NCSS Standards, p. -

Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines

Title: The Missing Sociological Imagination: Sociological Functionalist Theory That Shapes the Filipino Social Consciousness in the Philippines Author: Prof. Kathy Westman, Waubonsee Community College, Sugar Grove, IL Summary: This lesson explores the links on the development of sociology in the Philippines and the sociological consciousness in the country. The assumption is that limited growth of sociological theory is due to the parallel limited growth of social modernity in the Philippines. Therefore, the study of sociology in the Philippines takes on a functionalist orientation limiting development of sociological consciousness on social inequalities. Sociology has not fully emerged from a modernity tool in transforming Philippine society to a conceptual tool that unites Filipino social consciousness on equality. Objectives: 1. Study history of sociology in the Philippines. 2. Assess the application of sociology in context to the Philippine social consciousness. 3. Explore ways in which function over conflict contributes to maintenance of Filipino social order. 4. Apply and analyze the links between the current state of Philippine sociology and the threats on thought and freedoms. 5. Create how sociology in the Philippines can benefit collective social consciousness and of change toward social movements of equality. Content: Social settings shape human consciousness and realities. Sociology developed in western society in which the constructions of thought were unable to explain the late nineteenth century systemic and human conditions. Sociology evolved out of the need for production of thought as a natural product of the social consciousness. Sociology came to the Philippines in a non-organic way. Instead, sociology and the social sciences were brought to the country with the post Spanish American War colonization by the United States. -

Black Lives Matter: (Re)Framing the Next Wave of Black Liberation Amanda D

RESEARCH IN SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, CONFLICTS AND CHANGE RESEARCH IN SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, CONFLICTS AND CHANGE Series Editor: Patrick G. Coy Recent Volumes: Volume 27: Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change À Edited by Patrick G. Coy Volume 28: Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change À Edited by Patrick G. Coy Volume 29: Pushing the Boundaries: New Frontiers in Conflict Resolution and Collaboration À Edited by Rachel Fleishman, Catherine Gerard and Rosemary O’Leary Volume 30: Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change À Edited by Patrick G. Coy Volume 31: Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change À Edited by Patrick G. Coy Volume 32: Critical Aspects of Gender in Conflict Resolution, Peacebuilding, and Social Movements À Edited by Anna Christine Snyder and Stephanie Phetsamay Stobbe Volume 33: Media, Movements, and Political Change À Edited by Jennifer Earl and Deana A. Rohlinger Volume 34: Nonviolent Conflict and Civil Resistance À Edited by Sharon Erickson Nepstad and Lester R. Kurtz Volume 35: Advances in the Visual Analysis of Social Movments À Edited by Nicole Doerr, Alice Mattoni and Simon Teune Volume 36: Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change À Edited by Patrick G. Coy Volume 37: Intersectionality and Social Change À Edited by Lynne M. Woehrle Volume 38: Research in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change À Edited by Patrick G. Coy Volume 39: Protest, Social Movements, and Global Democracy since 2011: New Perspectives À Edited by Thomas Davies, Holly Eva Ryan and Alejandro Peña Volume 40: Narratives of Identity in Social Movements, Conflicts and Change À Edited by Landon E. -

Sociology and Social Anthropology Fall Term 2020 Social Movements

Sociology and Social Anthropology Fall Term 2020 Social Movements SOCL 5373 (2 credits) Instructor: Jean-Louis Fabiani [email protected] Social Movements have been From the start a central object of the social sciences: how do people behave collectively? How do they coordinate? What are the costs of a mobilization? What are the tools used (gatherings, voice, violence and so on) Who gets involved, and who does not? What triggers a movement, what makes it Fail? How are movements remembered and replicated in other settings? The First attempts to understand collective behavior developed in the area of crowd psychology, at the beginning of the 20th century: explaining the protesting behavior oF the dominated classes was the goal oF a rather conservative discourse that aimed to avoid disruptive attitudes. Gustave Lebon's rather pseudo-scientiFic attempts were a case in point: collective action was identiFied as a Form of panic or of madness. Later on, more sympathetic approaches appeared, since social movements were considered as an excellent illustration of a democratic state. Recently, globalization has brought about new objects oF contention but also the internationalization oF protests. Mobilizations in the post-socialist countries and the "Arab Springs" are characterized by new Forms of claims and new Forms of action. For many social scientists, their study demands a new theoretical and methodological equipment. The Field of social movements has been an innovative place For new concepts and new methods: "resource mobilization theory", "repertoire of action" and "eventful sociology" are good examples. Right now, this area oF study hosts the most intense, and perhaps the most exciting debates in the social sciences. -

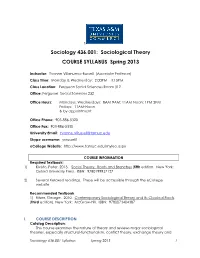

Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013

t Sociology 436.001: Sociological Theory COURSE SYLLABUS Spring 2013 Instructor: Yvonne Villanueva-Russell (Associate Professor) Class Time: Monday & Wednesday: 2:00PM – 3:15PM Class Location: Ferguson Social Sciences Room 312 Office: Ferguson Social Sciences 232 Office Hours: Mondays, Wednesdays: 8AM-9AM; 11AM-Noon; 1PM-2PM Fridays: 11AM-Noon & by appointment Office Phone: 903-886-5320 Office Fax: 903-886-5330 University Email: [email protected] Skype username: yvrussell1 eCollege Website: http://www.tamuc.edu/myleo.aspx COURSE INFORMATION Required Textbook: 1) Kivisto, Peter. 2013. Social Theory: Roots and Branches (fifth edition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN: 9780199937127 2) Several Xeroxed readings. These will be accessible through the eCollege website Recommended Textbook 1) Ritzer, George. 2010. Contemporary Sociological Theory and Its Classical Roots. (third edition). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN: 9780073404387 I. COURSE DESCRIPTION Catalog Description: This course examines the nature of theory and reviews major sociological theories, especially structural-functionalism, conflict theory, exchange theory and Sociology 436.001 Syllabus Spring 2013 1 interactionism. Special attention is given to leading figures representing the above schools of thought. Prerequisite: Sociology 111 or its equivalent. Student Learning Outcomes 1) Students will demonstrate comprehension of the major sociological theorist’s ideas and concepts as measured through examinations and online discussion boards 2) Students will demonstrate the ability to apply sociological concepts and theories through written essays Course Format: This course will revolve around numerous readings and active discussion in class of these selections, as well as lecture to supplement and provide background information on each theorist or theoretical paradigm. We will spend the bulk of time wading through and struggling to understand the writings through primary readings composed by the actual theorists, themselves. -

Theoretical Pluralism and Sociological Theory

ASA Theory Section Debate on Theoretical Work, Pluralism, and Sociological Theory Below are the original essay by Stephen Sanderson in Perspectives, the Newsletter of the ASA Theory section (August 2005), and the responses it received from Julia Adams, Andrew Perrin, Dustin Kidd, and Christopher Wilkes (February 2006). Also included is a lengthier version of Sanderson’s reply than the one published in the print edition of the newsletter. REFORMING THEORETICAL WORK IN SOCIOLOGY: A MODEST PROPOSAL Stephen K. Sanderson Indiana University of Pennsylvania Thirty-five years ago, Alvin Gouldner (1970) predicted a coming crisis of Western sociology. Not only did he turn out to be right, but if anything he underestimated the severity of the crisis. This crisis has been particularly severe in the subfield of sociology generally known as “theory.” At least that is my view, as well as that of many other sociologists who are either theorists or who pay close attention to theory. Along with many of the most trenchant critics of contemporary theory (e.g., Jonathan Turner), I take the view that sociology in general, and sociological theory in particular, should be thoroughly scientific in outlook. Working from this perspective, I would list the following as the major dimensions of the crisis currently afflicting theory (cf. Chafetz, 1993). 1. An excessive concern with the classical theorists. Despite Jeffrey Alexander’s (1987) strong argument for “the centrality of the classics,” mature sciences do not show the kind of continual concern with the “founding fathers” that we find in sociological theory. It is all well and good to have a sense of our history, but in the mature sciences that is all it amounts to – history. -

The Following Full Text Is a Publisher's Version

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/199928 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-27 and may be subject to change. SOCIAL MOVEMENT STUDIES 2018, VOL. 17, NO. 6, 736–748 https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2018.1499511 Articles reporting research on Latin American social movements are only rarely transparent Sven Da Silvaa, Peter A. Tamás b and Jarl K. Kampen b,c aSociology of Development and Change, Wageningen University, Wageningen, Netherlands; bBiometris, Wageningen University, Wageningen, Netherlands; cStatua, Dept Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Antwerp University, Antwerpen, Belgium ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Social movement scholars often want their research to make a dif- Received 5 December 2017 ference beyond the academy. Readers will either read reports directly Accepted 9 July 2018 fi or they will read reviews that aggregate ndings across a number of KEYWORDS fi reports. In either case, readers must nd reports to be credible before Systematic review; social they will take their findings seriously. While it is not possible to movements; Latin America; predict the indicators of credibility used by individual, direct readers, reporting standards; formal systems of review do explicate indicators that determine methodological whether a report will be recognized as credible for review. One transparency such indicator, also relevant to pre-publication peer review, is meth- odological transparency: the extent to which readers are able to detect how research was done and why that made sense. -

Anomie: Concept, Theory, Research Promise

Anomie: Concept, Theory, Research Promise Max Coleman Oberlin College Sociology Department Senior Honors Thesis April 2014 Table of Contents Dedication and Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 I. What Is Anomie? Introduction 6 Anomie in The Division of Labor 9 Anomie in Suicide 13 Debate: The Causes of Desire 23 A Sidenote on Dualism and Neuroplasticity 27 Merton vs. Durkheim 29 Critiques of Anomie Theory 33 Functionalist? 34 Totalitarian? 38 Subjective? 44 Teleological? 50 Positivist? 54 Inconsistent? 59 Methodologically Unsound? 61 Sexist? 68 Overly Biological? 71 Identical to Egoism? 73 In Conclusion 78 The Decline of Anomie Theory 79 II. Why Anomie Still Matters The Anomic Nation 90 Anomie in American History 90 Anomie in Contemporary American Society 102 Mental Health 120 Anxiety 126 Conclusions 129 Soldier Suicide 131 School Shootings 135 III. Looking Forward: The Solution to Anomie 142 Sociology as a Guiding Force 142 Gemeinschaft Within Gesellschaft 145 The Religion of Humanity 151 Final Thoughts 155 Bibliography 158 2 To those who suffer in silence from the pain they cannot reveal. Acknowledgements: I would like to thank Professor Vejlko Vujačić for his unwavering support, and for sharing with me his incomparable sociological imagination. If I succeed as a professor of sociology, it will be because of him. I am also deeply indebted to Émile Durkheim, who first exposed the anomic crisis, and without whom no one would be writing a sociology thesis. 3 Abstract: The term anomie has declined in the sociology literature. Apart from brief mentions, it has not featured in the American Sociological Review for sixteen years. Moreover, the term has narrowed and is now used almost exclusively to discuss deviance. -

Selina Rosa Gallo-Cruz, Phd Curriculum Vitae Winter 2021

Selina Rosa Gallo-Cruz, PhD Curriculum Vitae Winter 2021 Department of Sociology and Anthropology College of the Holy Cross Phone: 508-793-2288 1 College Street Fax: 508-793-3088 Worcester, MA 01610 [email protected] PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2019- Associate Professor, College of the Holy Cross 2013- 2019 Assistant Professor, College of the Holy Cross 2012-2013 Visiting Assistant Professor, Emory University 2012 Instructor, Agnes Scott College FELLOWSHIPS AND VISITING POSITIONS 2021-2022 Fulbright-Tampere University Scholar 2021-2022 Democracy Visiting Fellow, Ash Center, Harvard Kennedy School 2020-2021 Visiting Scholar, Brandeis University Women’s Studies Research Center 2016 Visiting Scholar, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque 2015 Gender and Peacebuilding Fellow, KROC Institute for International Peace Studies 2012 Summer Teaching Fellow, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee EDUCATION 2012 PhD Sociology, Emory University 2010 M.A. Sociology, Emory University Comprehensive Examinations: Culture, Contemporary Social Theory 2006 Wellesley College (cum laude) B.A., Sociology (Departmental Honors) AREAS OF SCHOLARSHIP Culture, Conflict, Gender, Global Change, NGOs, Nonviolence, Social Movements, Theory PUBLICATIONS Book Political Invisibility and Mobilization: Women against State Violence in Argentina, Yugoslavia, and Liberia Why are some social movement actors successful in periods of repression when other resistance efforts are swiftly and effectively quashed? What explains how politically marginalized women’s movements are able to build lasting and successful social movements amidst heightened violence, militarization against civilians, civil war, and genocide? Political Invisibility and Mobilization presents a multi-level framework for understanding how political invisibility affects the mobilization of marginalized groups. To do so, this Curriculum Vitae, Selina R. Gallo-Cruz 1 study explores the emergence and successes of three women’s movements against state violence in Argentina, the former Yugoslavia, and Liberia.