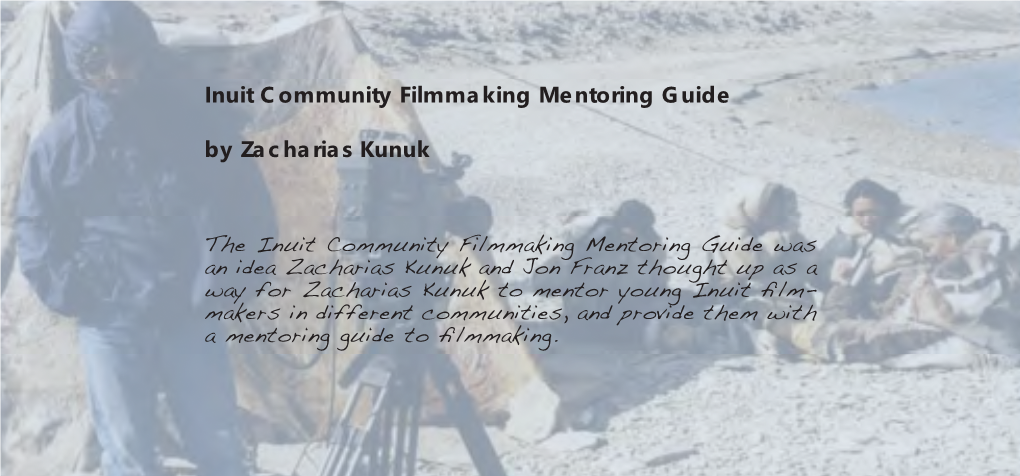

Inuit Community Filmmaking Mentoring Guide by Zacharias Kunuk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Nunavut, Canada

english cover 11/14/01 1:13 PM Page 1 FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove Principal Researchers: Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike FINAL REPORT OF THE INUIT BOWHEAD KNOWLEDGE STUDY NUNAVUT, CANADA By Inuit Study Participants from: Arctic Bay, Arviat, Cape Dorset, Chesterfield Inlet, Clyde River, Coral Harbour, Grise Fiord, Hall Beach, Igloolik, Iqaluit, Kimmirut, Kugaaruk, Pangnirtung, Pond Inlet, Qikiqtarjuaq, Rankin Inlet, Nunavut Wildlife Management Board Repulse Bay, and Whale Cove PO Box 1379 Principal Researchers: Iqaluit, Nunavut Keith Hay (Study Coordinator) and X0A 0H0 Members of the Inuit Bowhead Knowledge Study Committee: David Aglukark (Chairperson), David Igutsaq, MARCH, 2000 Joannie Ikkidluak, Meeka Mike Cover photo: Glenn Williams/Ursus Illustration on cover, inside of cover, title page, dedication page, and used as a report motif: “Arvanniaqtut (Whale Hunters)”, sc 1986, Simeonie Kopapik, Cape Dorset Print Collection. ©Nunavut Wildlife Management Board March, 2000 Table of Contents I LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES . .i II DEDICATION . .ii III ABSTRACT . .iii 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 RATIONALE AND BACKGROUND FOR THE STUDY . .1 1.2 TRADITIONAL ECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE AND SCIENCE . .1 2 METHODOLOGY 3 2.1 PLANNING AND DESIGN . .3 2.2 THE STUDY AREA . .4 2.3 INTERVIEW TECHNIQUES AND THE QUESTIONNAIRE . .4 2.4 METHODS OF DATA ANALYSIS . -

2017 New York

CANADA NOW BEST NEW FILMS FROM CANADA 2017 APRIL 6 – 9 AT THE IFC CENTER, NEW YORK From the recent numerous international successes of Canadian directors such as Xavier Dolan (Mommy, It’s Only the End of the World), Denis Villeneuve (Arrival, and the forthcoming Blade Runner sequel), Philippe Falardeau (The Bleeder, The Good Lie) and Jean-Marc Vallée (Dallas Buyers Club, Wild, Demolition), you might be thinking that there must be something special in that clean, cool drinking water north of the 49th parallel. As this year’s selection of impressive new Canadian films reveals, you would not be wrong. With works from new talents as well as from Canada’s accomplished veteran directors, this series will transport you from the Arctic Circle to western Asia, from downtown Montreal to small town Nova Scotia. And yes, there will be hockey. Get ready to travel across the daring and dramatic contemporary Canadian cinematic landscape. Have a look at what’s now and what’s next in those cinematic lights in the northern North American skies. Thursday, April 6, 7:00PM RUMBLE: THE INDIANS WHO ROCKED THE WORLD CANADA 2017 | 97 MINUTES DIRECTOR: CATHERINE BAINBRIDGE, CO-DIRECTOR: ALFONSO MAIORANA Artfully weaving North American musicology and the devastating historical experiences of Native Americans, Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked The World reveals the deep connections between Native American and African American peoples and their musical forms. A Sundance 2017 sensation, Bainbridge’s and co-director Maiorana’s documentary charts the rhythms and notes we now know as rock, blues, and jazz, and unveils their surprising origins in Native American culture. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

First Nation Filmmakers from Around the World 10

MEDIA RELEASE EMBARGOED UNTIL 11.00am WEDNESDAY 10 MAY 2017 FIRST NATION FILMMAKERS FROM AROUND THE WORLD The 64th Sydney Film Festival (7–18 June) in partnership with Screen Australia’s Indigenous Department proudly continues support for First Nation storytelling from Australia and around the world. Leading First Nation Australian directors will premiere their new works at the Festival, including Warwick Thornton’s Opening Night film and Official Competition contender We Don’t Need a Map, and Wayne Blair and Leah Purcell’s highly anticipated second series of Cleverman. “Sydney Film Festival is committed to showcasing First Nation filmmakers and storytelling,” said Festival Director Nashen Moodley. “Throughout the Festival audiences will find examples of outstanding Indigenous cinema, from the red sands of Western Australia to the snowy landscapes of the Arctic Circle. These films promise to surprise, provoke and push boundaries.” “We're proud to continue our partnership with Sydney Film Festival to showcase these powerful documentaries from the world's leading Indigenous filmmakers, as well as premiere the innovative work of emerging new talent from around the country,” said Penny Smallacombe, Head of Indigenous at Screen Australia. “We are very pleased to see five films commissioned by NITV take their place alongside such prestigious works from across the world,” said Tanya Orman, NITV Channel Manager. Two important Australian First Nation documentaries will also have their premieres at the Festival. Connection to Country, directed by Tyson Mowarin, about the Indigenous people of the Pilbara’s battle to preserve Australia’s 40,000-year-old cultural heritage from the ravages of mining, and filmmaker Erica Glynn’s raw, heartfelt and funny journey of adult Aboriginal students and their teachers as they discover the transformative power of reading and writing for the first time (In My Own Words). -

FACT SHEET Angjqatigiingniq – Deciding Together Digital Indigenous Democracy –

FACT SHEET Angjqatigiingniq – Deciding Together Digital Indigenous Democracy – www.isuma.tv/did • WHO? Isuma Distribution International Inc., with Nunavut Independent Television Network (NITV), Municipality of Igloolik, Nunavut Dept. of Culture, Language, Elders and Youth, Carleton University Centre for Innovation, Mount Allison University and LKL International. Project leaders, Zacharias Kunuk and Norman Cohn. Human Rights Assessor, Lloyd Lipsett. • WHAT? In complex multi-lateral high-stakes negotiations, Inuit consensus - deciding together – may be the strongest power communities can bring to the table with governments and transnational corporations working together. DID uses internet, community radio, local TV and social media to amplify Inuit traditional decision-making skills at a moment of crisis and opportunity: as Inuit face Environmental Review of the $6 billion Baffinland Iron Mine (BIM) on north Baffin Island. Through centuries of experience Inuit learned that deciding together, called angjqatigiingniq [ahng-ee-kha-te-GING-nik] in Inuktitut – a complex set of diplomatic skills for respectful listening to differing opinions until arriving at one unified decision everyone can support – is the smartest, safest way to go forward in a dangerous environment. Through DID, Inuit adapt deciding together to modern transnational development – to get needed information in language they understand, talk about their concerns publicly and reach collective decisions with the power of consensus. Inuit consensus then is presented in a multimedia Human Rights Impact Assessment (HRIA), looking at the positive and negative impacts of the proposed mine in terms of international human rights standards and best practices, to the regulatory process, online through IsumaTV and through local radio and TV channels in all Nunavut communities. -

Strategic Plan 2020-2025 English

Strategic Plan 2020-2025 FOREWORD In the twenty years since the creation of Nunavut, the screen-based media industry has changed significantly. It has witnessed dramatic changes: moving from analogue to digital; traditional broadcast to online streaming and linear channel viewing to mobile consumption. Since its establishment in 2004 by the Government of Nunavut, the Nunavut Film Development Corporation (NFDC) has been the organization best placed to foster the full economic and creative potential of the screen-based industry in Nunavut — increasing the strength and value of our content creator’s products, services, intellectual property and brand. Screen-based media are a desirable global commodity due to a multitude of economic impacts. There are many channels through which the screen-based industry contributes to a local economy, and the benefits can be measured in three ways: 1. Direct impacts related to the actual stages of production (development/pre-production, production, postproduction, distribution). 2. Indirect impacts in support of production (equipment, construction, transport, advertising, legal, accounting, financial banking). 3. Cross-sectoral impacts that spill over into other parts of the territorial economy (labour, skills development, tourism, retail/entertainment, trade, cultural). In 2015, Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada published a report outlining that Inuit artists and creative workers in the industries of film, media, writing and publishing contributed $9.8 million to GDP in Canada. The resulting economic activity created or supported an additional 208 full time equivalent jobs. NFDC’s most recent data on its activities in 2018-2019 outline the following: · Funded $1,235 million for projects in 7 program categories. -

November 30, 2019 ᖃᒡᒋᖅ

ᖃᒡᒋᖅ (ᑲᑎᑦᑕᕐᕕᒃ) Qaggiq: Gathering Place September 18– November 30, 2019 Works by Curated by asinnajaq and Barbara Fischer Presented with the support of the Jackman Humanities Institute, University of Toronto Presented in partnership with Toronto Biennial of Art ᖃᒡᒋᖅ (ᑲᑎᑦᑕᕐᕕᒃ) Qaggiq: Gathering Place Cover: Isuma, Hunting with my Ancestors Episode 1: Bowhead Whale Hunt, 2018. Courtesy of Isuma and Vtape. Right: Isuma, The Journals of Knud Rasmussen, 2006. Courtesy of Isuma and Vtape. Our name Isuma means “to think," as in Isuma: film and video Thinking Productions. Our building in the from an Inuit point of view centre of Igloolik has a big sign on the front that says Isuma. Think. Young and old work together to keep our ancestors' knowledge alive. We create traditional artifacts, digital multimedia, and desperately needed jobs in the same activity. Our productions give an artist's view for all to see where we came from: what Inuit were able to do then and what we are able to do now. —Zacharias Kunuk Above and below right: Isuma, The Journals of Knud Rasmussen, 2006. Courtesy of Isuma and Vtape. Middle: Isuma, Hunting with my Ancestors Episode 1: Bowhead Whale Hunt, 2018. Courtesy of Isuma and Vtape. Above right: Isuma, Qapirangajuq: Inuit Knowledge and Climate Change, 2010. Courtesy of Isuma and Vtape. ᖃᒡᒋᖅ (ᑲᑎᑦᑕᕐᕕᒃ) Qaggiq: Gathering Place Isuma, Hunting with my Ancestors Episode 1: Bowhead Whale Hunt, 2018. Courtesy of Isuma and Vtape. In 1990, Zacharias Kunuk, Paul Apak Angilirq, and a warrior's epic endurance. It was not expand access for and to Inuit and Indigenous The curators have invited guest artist Couzyn Pauloosie Qulitalik, and Norman Cohn founded only the first feature film produced entirely in productions, using low-bandwidth internet to van Heuvelen into the exhibition of Isuma’s Igloolik Isuma Productions Inc. -

National Gallery of Art

ADMISSION IS FREE DIRECTIONS 10:00 TO 5:00 National Gallery of Art Release Date: June 21, 2017 National Gallery of Art 2017 Summer Film Program Includes Washington Premieres, Special Appearances, New Restorations, Retrospectives, Tributes to Canada and to French Production House Gaumont, Discussions and Book Signings with Authors, and Collaboration with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Film still from The Savage Eye (Ben Maddow, Joseph Strick, and Sidney Meyers, 1959, 35mm, 68 minutes), to be shown at the National Gallery of Art on Saturday, September 9, at 4:00 p.m., as part of the film series From Vault to Screen: Recent Restorations from the Academy Film Archive. Image courtesy of Photofest. Washington, DC—The National Gallery of Art is pleased to announce that the 2017 summer film program will include more than 40 screenings: several Washington premieres; special appearances and events; new restorations of past masterworks; a salute to Canada; a special From Vault to Screen series; and a family documentary by Elissa Brown, daughter of J. Carter Brown, former director of the National Gallery of Art. Film highlights for the summer include the premiere of Albert Serra's acclaimed new narrative Death of Louis XIV. The seven-part series Saluting Canada at 150 honors the sesquicentennial of the Canadian Confederation. A six-part series, Cinéma de la révolution: America Films Eighteenth- Century France, offers a brief look at how Hollywood has interpreted the lavish culture and complex history of 18th-century France. The screening coincides with the summer exhibition America Collects Eighteenth-Century French Paining, on view in the West Building through August 20 (http://www.nga.gov/content/ngaweb/press/exh/3683.html). -

Puvalluqatatiluta, When We Had Tuberculosis

PUVALUQATATILUTA, WHEN WE HAD TUBERCULOSIS PUVALUQATATILUTA, WHEN WE HAD TUBERCULOSIS: ST. LUKE'S MISSION HOSPITAL AND THE INUIT OF THE CUMBERLAND SOUND REGION, 1930–1972 By E. EMILY S. COWALL, DHMSA, M.Sc. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by E. Emily S. Cowall, November 2011 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2011) McMaster University (Anthropology) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Puvaluqatatiluta, When We Had Tuberculosis: St. Luke's Mission Hospital and the Inuit of the Cumberland Sound Region, 1930–1972 AUTHOR: E. Emily S. Cowall, DHMSA (Society of Apothecaries), M.Sc. (University of Edinburgh) SUPERVISOR: Professor D. Ann Herring NUMBER OF PAGES: xii, 183 ii ABSTRACT This thesis explores the history of Church- and State-mediated tuberculosis treatment for Inuit of the Cumberland Sound region from 1930 to 1972. Pangnirtung’s St. Luke’s Mission Hospital sits at the centre of this discussion and at the nexus of archival evidence and regional Inuit knowledge about tuberculosis. Triangulating information gained from fieldwork, archives, and a community-based photograph naming project, this study brings together the perspectives of Inuit hospital workers, nurses, doctors, and patients, as well as of Government and Anglican-Church officials, during the tuberculosis era in the Cumberland Sound. The study arose from conversations with Inuit in Pangnirtung, who wondered why they were sent to southern sanatoria in the 1950s for tuberculosis treatment, when the local hospital had been providing treatment for decades. Canadian Government policy changes, beginning in the 1940s, changed the way healthcare was delivered in the region. The Pangnirtung Photograph Naming Project linked photos of Inuit patients sent to the Hamilton Mountain Sanatorium to day-book records of St. -

Communicating Climate Change: Arctic Indigenous Peoples As Harbingers of Environmental Change

Communicating Climate Change: Arctic Indigenous Peoples as Harbingers of Environmental Change Erica Dingman Through various science-related and media channels Arctic indigenous peoples and western society have moved closer to a balanced account of Arctic environmental change. Focusing on the role of polar scientist and Inuit media makers, this article articulates the process through which a cross-cultural exchange of environmental knowledge is beginning to occur. At the intersection of Traditional Knowledge with western science and new media technology, a nascent but significant shift in practice is providing pathways to a ‘trusted’ exchange of Arctic climate change knowledge. Potentially, both could influence our global understanding of climate change. Introduction While the influence of Arctic indigenous voices on our Western understanding of climate change is not readily discernible in mainstream media, advances in media technologies, decades of indigenous political organization and shifting attitudes toward Traditional Knowledge (TK) and its relationship with Western scientific research have greatly contributed to the broader lexicon of environmental knowledge. However, in so far as the current global climate change discourse favors Western-based scientifically driven evidence, the complexity of environmental knowledge has demanded inclusion of contextualized knowledge. In the Arctic specifically, research regarding environmental change is Erica Dingman is an Associate Fellow at the World Policy Institute, USA. 2 Arctic Yearbook 2013 increasingly likely to result from the collaboration of Western scientists and local communities. In aggregate, this suggests that Arctic indigenous peoples are attaining a higher degree of recognition as primary producers of environmental knowledge. Relevant in many different respects is the involvement of Arctic indigenous peoples as political actors at the international, national, regional and sub-regional level. -

Peter Pitseolak and Zacharias Kunuk on Reclaiming Inuit Photographic Images and Imaging

Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society Vol. 3, No. 1, 2014, pp. 48-72 Control mapping: Peter Pitseolak and Zacharias Kunuk on reclaiming Inuit photographic images and imaging David Winfield Norman University of Oslo Abstract Inuit have been participating in the development of photo-reproductive media since at least the 19th century, and indeed much earlier if we continue on Michelle Raheja’s suggestion that there is much more behind Nanook’s smile than Robert Flaherty would have us believe. This paper examines how photographer Peter Pitseolak (1902-1973) and filmmaker Zacharias Kunuk have employed photography and film in relation to Raheja’s notion of “visual sovereignty” as a process of infiltrating media of representational control, altering their principles to visualize Indigenous ownership of their images. For camera-based media, this pertains as much to conceptions of time, continuity and “presence,” as to the broader dynamics of creative retellings. This paper will attempt to address such media-ontological shifts – in Pitseolak’s altered position as photographer and the effect this had on his images and the “presence” of his subjects, and in Kunuk’s staging of oral histories and, through the nature of film as an experience of “cinematic time,” composing time in a way that speaks to Inuit worldviews and life patterns – as radical renegotiations of the mediating properties of photography and film. In that they displace the Western camera’s hegemonic framing and time-based structures, repositioning Inuit “presence” and relations to land within the fundamental conditions of photo-reproduction, this paper will address these works from a position of decolonial media aesthetics, considering the effects of their works as opening up not only for more holistic, community-grounded representation models, but for expanding these relations to land and time directly into the expanded sensory field of media technologies. -

Our Baffinland: Digital Indigenous Democracy

ECONOMY Our Baffinland: Digital Indigenous Democracy Norman Cohn & Zacharias Kunuk s an upsurge of development due to global gency for Baffin Island Inuit facing one of the largest warming threatens to overwhelm communities mining developments in Canadian history. Baffinland iAn the resource-rich Canadian Arctic, how can Inuit Iron Mines Corporation’s (BIM) Mary River project in those communities be more fully involved and consulted is a $6 billion open-pit extraction of extremely high- in their own language? What tools are needed to grade iron ore that, if fully exploited, could continue make knowledgeable decisions? Communicating in for 100 years. The mining site, in the centre of North writing with oral cultures makes ‘consulting’ one- Baffin Island about half-way between the Inuit com- sided: giving people thousands of pages they can’t munities of Pond Inlet and Igloolik, requires a 150 read is unlikely to produce an informed, meaningful km railroad built across frozen tundra to transport response. Now for the first time Internet audiovisual ore to a deep-water port where the world’s largest su- tools enable community-based decision-making in pertankers will carry it to European and Asian mar- oral Inuktitut that meets higher standards of consti- kets. Operating the past several years under a tutional and international law, and offers a new temporary exploratory permit, BIM filed its Final En- model for development in Indigenous homelands. To vironmental Impact Statement (FEIS) with the Nunavut meet these standards, Inuit must get