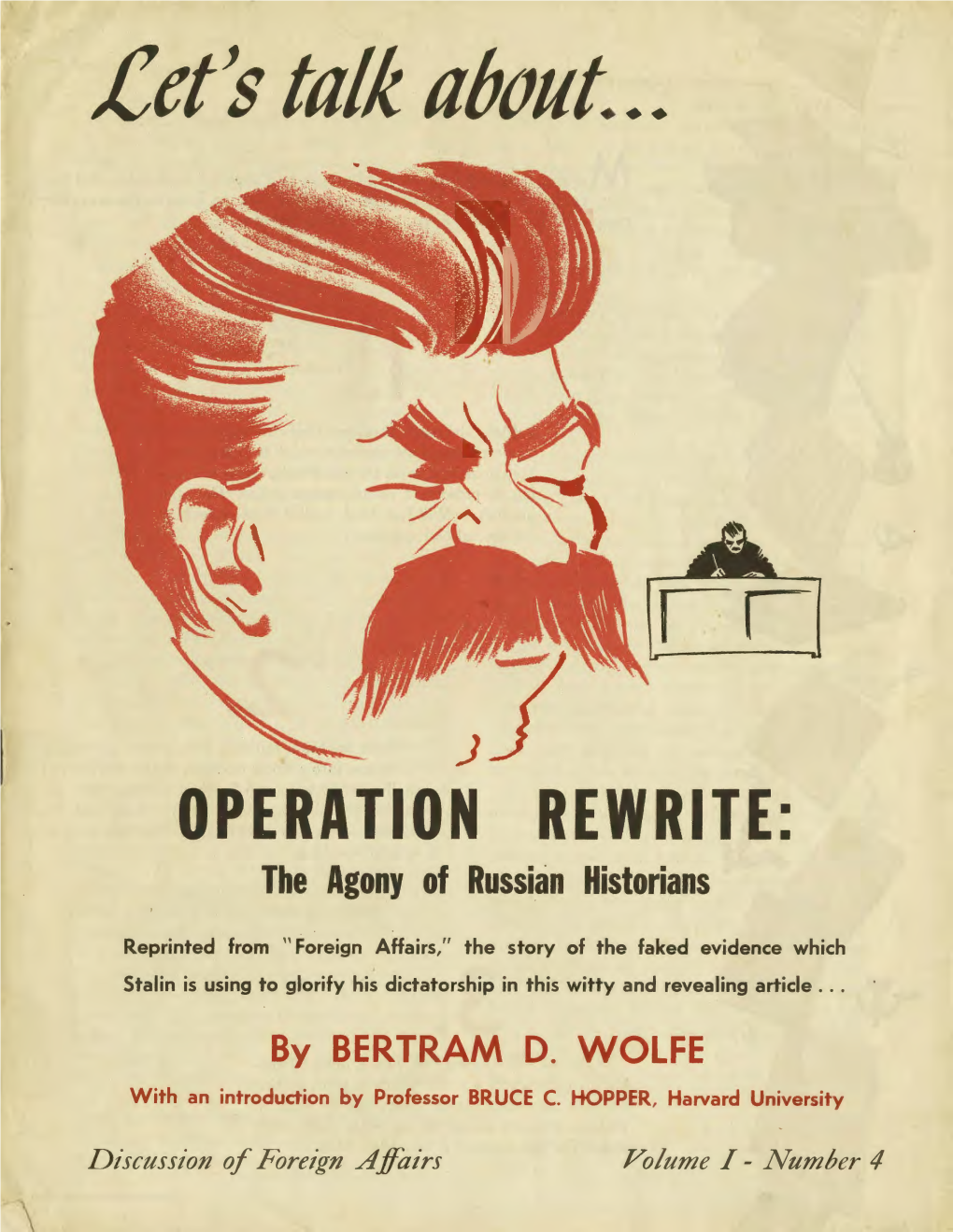

OPERATION REWRITE: the Agony of Russian Historians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Overview of Russian Foreign Policy

02-4498-6 ch1.qxd 3/25/02 2:58 PM Page 7 1 AN OVERVIEW OF RUSSIAN FOREIGN POLICY Forging a New Foreign Policy Concept for Russia Russia’s entry into the new millennium was accompanied by qualitative changes in both domestic and foreign policy. After the stormy events of the early 1990s, the gradual process of consolidating society around a strengthened democratic gov- ernment took hold as people began to recognize this as a requirement if the ongoing political and socioeconomic transformation of the country was to be successful. The for- mation of a new Duma after the December 1999 parliamen- tary elections, and Vladimir Putin’s election as president of Russia in 2000, laid the groundwork for an extended period of political stability, which has allowed us to undertake the devel- opment of a long-term strategic development plan for the nation. Russia’s foreign policy course is an integral part of this strategic plan. President Putin himself has emphasized that “foreign policy is both an indicator and a determining factor for the condition of internal state affairs. Here we should have no illusions. The competence, skill, and effectiveness with 02-4498-6 ch1.qxd 3/25/02 2:58 PM Page 8 which we use our diplomatic resources determines not only the prestige of our country in the eyes of the world, but also the political and eco- nomic situation inside Russia itself.”1 Until recently, the view prevalent in our academic and mainstream press was that post-Soviet Russia had not yet fully charted its national course for development. -

Ivan Vladislavovich Zholtovskii and His Influence on the Soviet Avant-Gavde

87T" ACSA ANNUAL MEETING 125 Ivan Vladislavovich Zholtovskii and His Influence on the Soviet Avant-Gavde ELIZABETH C. ENGLISH University of Pennsylvania THE CONTEXT OF THE DEBATES BETWEEN Gogol and Nikolai Nadezhdin looked for ways for architecture to THE WESTERNIZERS AND THE SLAVOPHILES achieve unity out of diverse elements, such that it expressed the character of the nation and the spirit of its people (nnrodnost'). In the teaching of Modernism in architecture schools in the West, the Theories of art became inseparably linked to the hotly-debated historical canon has tended to ignore the influence ofprerevolutionary socio-political issues of nationalism, ethnicity and class in Russia. Russian culture on Soviet avant-garde architecture in favor of a "The history of any nation's architecture is tied in the closest manner heroic-reductionist perspective which attributes Russian theories to to the history of their own philosophy," wrote Mikhail Bykovskii, the reworking of western European precedents. In their written and Nikolai Dmitriev propounded Russia's equivalent of Laugier's manifestos, didn't the avantgarde artists and architects acknowledge primitive hut theory based on the izba, the Russian peasant's log hut. the influence of Italian Futurism and French Cubism? Imbued with Such writers as Apollinari Krasovskii, Pave1 Salmanovich and "revolutionary" fervor, hadn't they publicly rejected both the bour- Nikolai Sultanov called for "the transformation. of the useful into geois values of their predecessors and their own bourgeois pasts? the beautiful" in ways which could serve as a vehicle for social Until recently, such writings have beenacceptedlargelyat face value progress as well as satisfy a society's "spiritual requirements".' by Western architectural historians and theorists. -

The Inextricable Link Between Literature and Music in 19Th

COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Ashley Shank December 2010 COMPOSERS AS STORYTELLERS: THE INEXTRICABLE LINK BETWEEN LITERATURE AND MUSIC IN 19TH CENTURY RUSSIA Ashley Shank Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Interim Dean of the College Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Dudley Turner _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Dean of the Graduate School Mr. George Pope Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ _______________________________ School Director Date Dr. William Guegold ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I. OVERVIEW OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECULAR ART MUSIC IN RUSSIA……..………………………………………………..……………….1 Introduction……………………..…………………………………………………1 The Introduction of Secular High Art………………………………………..……3 Nicholas I and the Rise of the Noble Dilettantes…………………..………….....10 The Rise of the Russian School and Musical Professionalism……..……………19 Nationalism…………………………..………………………………………..…23 Arts Policies and Censorship………………………..…………………………...25 II. MUSIC AND LITERATURE AS A CULTURAL DUET………………..…32 Cross-Pollination……………………………………………………………...…32 The Russian Soul in Literature and Music………………..……………………...38 Music in Poetry: Sound and Form…………………………..……………...……44 III. STORIES IN MUSIC…………………………………………………… ….51 iii Opera……………………………………………………………………………..57 -

Eurr 4203/5203 and Hist 4603/5603 Imperial and Soviet Russia Wed 8:35-11:25, Dunton Tower 1006

Eurr 4203/5203 and Hist 4603/5603 Imperial and Soviet Russia Wed 8:35-11:25, Dunton Tower 1006 Dr. Johannes Remy Winter 2014 Office: 3314 River Building e-mail: [email protected] Office Hours: Wednesday 3:00-4:00p.m. Phone: To be announced This course will analyze fundamental political, social, and cultural changes across the lands of the Russian Empire and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This seminar course will focus on major topics in the history and historiography of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union. Themes to be explored include political culture, empire and nationality questions, socialism, revolution, terror, class and gender. In the Napoleonic wars, Russia gained greater international prestige and influence than it had ever before. However, it was evident for many educated Russians that their country was “backward” compared to the Western Europe in its social and political system and economic performance. Russia retained serfdom longer than any other European country, until 1861, and the citizens gained representative bodies with legislative prerogatives only in 1905-1906, after all the other European countries except the Ottoman Empire. Many educated people lost their trust in the government and adopted radical, leftist and revolutionary ideologies. Even after the abolition of serfdom, the relations between peasants and noble landowners contained elements of antagonism. Industrialization began in the 1880s and brought additional problems, since radical intelligentsia managed to establish connections with discontented workers. In the course of the nineteenth century, the traditional policy of co-operation with local elites of ethnic minorities was challenged by both Russian and minority nationalisms. -

Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century Joshua J

Cedarville University DigitalCommons@Cedarville The Research and Scholarship Symposium The 2016 yS mposium Apr 20th, 3:40 PM - 4:00 PM Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century Joshua J. Taylor Cedarville University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/ research_scholarship_symposium Part of the Musicology Commons Taylor, Joshua J., "Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century" (2016). The Research and Scholarship Symposium. 4. http://digitalcommons.cedarville.edu/research_scholarship_symposium/2016/podium_presentations/4 This Podium Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Cedarville, a service of the Centennial Library. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Research and Scholarship Symposium by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Cedarville. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Musically Russian: Nationalism in the Nineteenth Century What does it mean to be Russian? In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Russian nobility was engrossed with French culture. According to Dr. Marina Soraka and Dr. Charles Ruud, “Russian nobility [had a] weakness for the fruits of French civilization.”1 When Peter the Great came into power in 1682-1725, he forced Western ideals and culture into the very way of life of the aristocracy. “He wanted to Westernize and modernize all of the Russian government, society, life, and culture… .Countries of the West served as the emperor’s model; but the Russian ruler also tried to adapt a variety of Western institutions to Russian needs and possibilities.”2 However, when Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Russia in 1812, he threw the pro- French aristocracy in Russia into an identity crisis. -

12. the Tsar and Empire: Representation of the Monarchy and Symbolic Integration in Imperial Russia $

12. The Tsar and Empire: Representation of the Monarchy and Symbolic Integration in Imperial Russia $ ymbolic representation played a central role in defi ning the concept of S monarchical sovereignty in Russia. In the absence of native traditions of supreme power, Russian tsars invoked and emulated foreign images of rule to elevate themselves and the state elite above the subject population. Th e source of sacrality was distant from Russia, whether it was located beyond the sea whence the original Viking princes came, according to the tale of the invitations of the Varangians, or fi xed in an image of Byzantium, France, or Germany.1 Th e centrality of conquest in the representations of Russian rulers contrasts with the mythical history of the Hapsburg emperors, which legitimized the expansion of imperial dominion through marriage.2 From the fi fteenth century, when Ivan III refused the title of king from the Holy Roman Emperor with the declaration that he “had never wanted to be made king by anyone,” Russian monarchs affi rmed and reaffi rmed the imperial character of their rule, evoking the images of Byzantine and later Roman and European imperial dominion. Beginning with Ivan IV’s conquests of Kazan and Astrakhan, they 1 On the symbolic force of foreignness see Ju. M. Lotman and B. A. Uspenskii, “Th e Role of Dual Models in the Dynamics of Russian Culture (Up to the End of the Eighteenth Century),” in Ju. M. Lotman and B. A. Uspenskii, Th e Semiotics of Russian Culture, ed. Ann Shukman (Ann Arbor: Michigan Slavic Contributions, 1984), 3-35. -

A Short History of Russia (To About 1970)

A Short History of Russia (to about 1970) Foreword. ...............................................................................3 Chapter 1. Early History of the Slavs, 2,000 BC - AD 800. ..........4 Chapter 2. The Vikings in Russia.............................................6 Chapter 3. The Adoption of Greek Christianity: The Era of Kievan Civilisation. ..........................................................7 Chapter 4. The Tatars: The Golden Horde: The Rise of Moscow: Ivan the Great. .....................................................9 Chapter 5. The Cossacks: The Ukraine: Siberia. ...................... 11 Chapter 6. The 16th and 17th Centuries: Ivan the Terrible: The Romanoffs: Wars with Poland. .............................. 13 Chapter 7. Westernisation: Peter the Great: Elizabeth.............. 15 Chapter 8. Catherine the Great............................................. 17 Chapter 9. Foreign Affairs in the 18th Century: The Partition of Poland. .............................................................. 18 Chapter 10. The Napoleonic Wars. .......................................... 20 Chapter 11. The First Part of the 19th Century: Serfdom and Autocracy: Turkey and Britain: The Crimean War: The Polish Rebellion................................................... 22 Chapter 12. The Reforms of Alexander II: Political Movements: Marxism. ........................................................... 25 Chapter 13. Asia and the Far East (the 19th Century) ................ 28 Chapter 14. Pan-Slavism....................................................... -

History of Russia to 1855 Monday / Wednesday / Friday 3:30-4:30 Old Main 002 Instructor: Dr

HIST 294-04 Fall 2015 History of Russia to 1855 Monday / Wednesday / Friday 3:30-4:30 Old Main 002 Instructor: Dr. Julia Fein E-mail: j [email protected] Office: Old Main 300, x6665 Office hours: Open drop-in on Thursdays, 1-3, and by appointment COURSE DESCRIPTION Dear historians, Welcome to the first millennium of Russian history! We have a lively semester in front of us, full of famous, infamous, and utterly unknown people: from Ivan the Terrible, to Catherine the Great, to the serfs of Petrovskoe estate in the 19th century. Most of our readings will be primary documents from medieval, early modern, and 19th-century Russian history, supplemented with scholarly articles and book sections to provoke discussion about the diversity of possible narratives to be told about Russian history—or any history. We will also examine accounts of archaeological digs, historical maps, visual portrayals of Russia’s non-Slavic populations, coins from the 16th and 17th centuries, and lots of painting and music. As you can tell from our Moodle site, we will be encountering a lot of Russian art that was made after the period with which this course concludes. Isn’t this anachronistic? One of our course objectives deals with constructions of Russian history within R ussian history. We will discuss this issue most explicitly when reading Vasily Kliuchevsky on Peter the Great’s early life, and the first 1 HIST 294-04 Fall 2015 part of Nikolai Karamzin’s M emoir , but looking at 19th- and 20th-century artistic portrayals of medieval and early modern Russian history throughout also allows us to conclude the course with the question: why are painters and composers between 1856 and 1917 so intensely interested in particular moments of Russia’s past? What are the meanings of medieval and early modern Russian history to Russians in the 19th and 20th centuries? The second part of this course sequence—Revolutionary Russia and the Soviet Union—picks up this thread in spring semester. -

Novorossiya: a Launching Pad for Russian Nationalists

Novorossiya: A Launching Pad for Russian Nationalists PONARS Eurasia Policy Memo No. 357 September 2014 Marlene Laruelle The George Washington University The Ukraine crisis is a game changer for Russia’s domestic landscape. One of the most eloquent engines of this is the spread of the concept of “Novorossiya,” or New Russia. With origins dating from the second half of the 18th century, the term was revived during the Ukraine crisis and gained indirect official validation when Russian President Vladimir Putin used it during a call-in show in April 2014 to evoke the situation of the Russian-speaking population of Ukraine. It appeared again in May when the self- proclaimed Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics (DNR and LNR) decided to unite in a “Union of Novorossiya.” In August, a presidential statement was addressed to the “Insurgents of Novorossiya,” though the text itself referred only to “representatives of the Donbas.” The powerful pull of Novorossiya rests on its dual meaning in announcing the birth of a New Russia geographically and metaphorically. It is both a promised land to be added to Russia and an anticipation of Russia’s own transformation. As such, “Novorossiya” provides for an exceptional convergence of three underlying ideological paradigms that I briefly analyze here. “Red” Novorossiya The first ideological motif nurturing Novorossiya emphasizes Soviet memory. Novorossiya is both a spatial and ideological gift to Russia’s reassertion as a great power: it brings new territory and a new mission. This inspiration enjoys consensus among the Russian population and is widely shared by Russian nationalists and the Kremlin. -

George Kennan and the Challenge of Siberia

George Kennan and the Challenge of Siberia NICHOLAS DANILOFF he small boy pressed his nose against the window. He could hardly pass up T the chance to see the doctor treat his playmate, whose arm had been man- gled in the cogwheels of a mill. Through the pane, the boy spied the surgeon unsheathe a saw and carefully draw its razor-sharp teeth across the injured arm below the elbow. With horror, many years later, the boy at the window would describe the amputation: The surgeon accidentally let slip the end of one of the severed arteries and a jet of warm blood spurted from the stump of the upper arm to the inside of the window pane against which my face was pressed. The effect upon me was a sensation that I never felt before in all my boyish life—a sensation of deadly nausea, faintness and overwhelming fear.1 The peeping boy of 1855 would grow up to be the adventurous traveler George Kennan, a cousin twice removed of the twentieth-century George F. Kennan, American ambassador to Stalin’s Russia. Years after the operation, the nineteenth- century Kennan would succeed in amputating his own insecurities to brave the wilds of Siberia, to expose the horrors of the Russian penal system, and to become America’s first great authority on Russia. George Kennan, the elder, first intrigued me when I worked in Moscow as a journalist during the cold war over a hundred years later. I was drawn into the search for Kennan’s traces when I began researching the life of my own great- great-grandfather, a Russian exiled to Siberia for conspiring to overthrow the czar in 1825. -

Siberiaâ•Žs First Nations

TITLE: SIBERIA'S FIRST NATIONS AUTHOR: GAIL A. FONDAHL, University of Northern British Columbia THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR SOVIET AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH TITLE VIII PROGRAM 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 PROJECT INFORMATION:1 CONTRACTOR: Dartmouth College PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR: Gail A. Fondahl COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER: 808-28 DATE: March 29, 1995 COPYRIGHT INFORMATION Individual researchers retain the copyright on work products derived from research funded by Council Contract. The Council and the U.S. Government have the right to duplicate written reports and other materials submitted under Council Contract and to distribute such copies within the Council and U.S. Government for their own use, and to draw upon such reports and materials for their own studies; but the Council and U.S. Government do not have the right to distribute, or make such reports and materials available, outside the Council or U.S. Government without the written consent of the authors, except as may be required under the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act 5 U.S.C. 552, or other applicable law. 1 The work leading to this report was supported in part by contract funds provided by the National Council for Soviet and East European Research, made available by the U. S. Department of State under Title VIII (the Soviet-Eastern European Research and Training Act of 1983, as amended). The analysis and interpretations contained in the report are those of the author(s). CONTENTS Executive Summary i Siberia's First Nations 1 The Peoples of the -

Scandinavian Influence in Kievan Rus

Katie Lane HST 499 Spring 2005 VIKINGS IN THE EAST: SCANDINAVIAN INFLUENCE IN KIEVAN RUS The Vikings, referred to as Varangians in Eastern Europe, were known throughout Europe as traders and raiders, and perhaps the creators or instigators of the first organized Russian state: Kievan Rus. It is the intention of this paper to explore the evidence of the Viking or Varangian presence in Kievan Rus, more specifically the areas that are now the Ukraine and Western Russia. There is not an argument over whether the Vikings were present in the region, but rather over the effect their presence had on the native Slavic people and their government. This paper will explore and explain the research of several scholars, who generally ascribe to one of the rival Norman and Anti- Norman Theories, as well as looking at the evidence that appears in the Russian Primary Chronicle, some of the laws in place in the eleventh century, and two of the Icelandic Sagas that take place in modern Russia. The state of Kievan Rus was the dominant political entity in the modern country the Ukraine and western Russia beginning in the tenth century and lasting until Ivan IV's death in 1584.1 The region "extended from Novgorod on the Volkhov River southward across the divide where the Volga, the West Dvina, and the Dnieper Rivers all had their origins, and down the Dnieper just past Kiev."2 It was during this period that the Slavs of the region converted to Christianity, under the ruler Vladimir in 988 C.E.3 The princes that ruled Kievan Rus collected tribute from the Slavic people in the form of local products, which were then traded in the foreign markets, as Janet Martin explains: "The Lane/ 2 fur, wax, and honey that the princes collected from the Slav tribes had limited domestic use.