(Elasmobranchii: Carcharhiniformes) in the Pliocene of the Mediterranean Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Nostra Rete Lastra a Signa

LA NOSTRA RETE Un sostegno ai nostri produttori locali è un contributo importante alla nostra tavola, alla nostra salute, ad un mondo più buono, pulito e giusto. Nonostante la situazione critica, i produttori della rete Slow Food Scandicci continuano ad impegnarsi per un mondo sostenibile, ora più che mai. Qui di seguito la lista dei loro contatti e con un * prima del nome per chi si è potuto organizzare per le consegne a domicilio (almeno per questo periodo di #stiamoacasa). LASTRA A SIGNA * BUCOLICA – Circolo Culturale Agricolo www.bucolica.farm – [email protected] – 3452438158 Prodotti di fattoria e non solo (Bottarga di gallina, Cestino pranzo, Tisane, Farina, Miele, Biscotti...). L'ordine si può fare direttamente online dalla pagina prodotti del sito web. Minimo d’ordine € 20,00 e pagamento tramite Paypal o carta di credito. Gli ordini fatti entro il venerdì vengono consegnati il sabato pomeriggio. Per i residenti nel comune di Lastra a Signa gli ordini possono essere ritirati in fattoria la domenica mattina dalle 09h00-13h00. (Per chi fosse interessato, La Bucolica regala pasta madre a chi ne vuole per panificare a casa). * I COLLI DI MARLIANO – Azienda Agricola www.collimarliano.it – [email protected] – 3703305099 Vino, Birra artigianale, Pasta grani antichi, Farina bio, Uova, Miele…. Prodotti in dettaglio su www.slowfoodscandicci.it/rete/collimarliano.jpg e su Facebook. Per ordinazioni e consegna a domicilio chiamare 3703305099. Ordine minimo € 20,00. Consegne nei giorni di martedi e venerdi nelle aree di Firenze, Lastra a Signa, Scandicci, Signa Montelupo. * LA BOTTEGA DELLA CARNE di Marco e Roberto Petrucciani Via Armando Diaz 5, Lastra a Signa – 055872018 – 3388937943 Macelleria. -

Graduatoria Definitiva (Prot

COLLOCAMENTO MIRATO LEGGE 68/99 FIRENZE ENTE: AGENZIA NAZIONALE PER LA SICUREZZA DELLE FERROVIE Selezione Numerica N. 6/2019 - Richiesta: N. 2 “OPERATORE” (Cat.A1) Graduatoria Definitiva (prot. N. 7863 del 17/01/2020) Punt. Punt. Punt. Punt. Ammesso Pos. N.Prot. Centro Impiego Punt. Totale Anzianita Carico Reddito Invalidita con riserva 1 140035 SESTO FIORENTINO 118,00 0,00 0,00 28,00 1090,00 x 2 138381 PONTASSIEVE 127,00 0,00 6,00 28,00 1105,00 x 3 139246 SESTO FIORENTINO 158,00 0,00 0,00 28,00 1130,00 4 138673 FIRENZE 183,00 12,00 0,00 7,50 1163,50 5 137920 SCANDICCI 194,00 0,00 0,00 16,00 1178,00 FIGLINE E INCISA 6 141588 195,00 0,00 0,00 11,50 1183,50 VALDARNO 7 138782 CASTELFIORENTINO 174,00 0,00 18,00 7,50 1184,50 x 8 140258 SESTO FIORENTINO 208,00 0,00 0,00 20,00 1188,00 x 9 137848 SESTO FIORENTINO 200,00 0,00 0,00 7,50 1192,50 10 136732 SCANDICCI 214,00 0,00 0,00 11,50 1202,50 11 135960 SESTO FIORENTINO 233,00 0,00 0,00 20,00 1213,00 12 135852 FIRENZE 251,00 0,00 0,00 24,00 1227,00 13 141709 FIRENZE 245,00 0,00 0,00 7,50 1237,50 14 139716 BORGO SAN LORENZO 257,00 0,00 2,00 16,00 1243,00 15 138025 SESTO FIORENTINO 250,00 0,00 12,00 16,00 1246,00 16 141575 EMPOLI 290,00 24,00 0,00 20,00 1246,00 18 139038 EMPOLI 272,00 0,00 3,00 28,00 1247,00 17 135599 FIRENZE 289,00 12,00 0,00 28,00 1249,00 19 140296 EMPOLI 259,00 0,00 0,00 7,50 1251,50 20 139712 SCANDICCI 300,00 24,00 1,00 20,00 1257,00 21 141011 BORGO SAN LORENZO 270,00 0,00 0,00 11,50 1258,50 23 138469 SESTO FIORENTINO 289,00 0,00 0,00 16,00 1273,00 22 141696 FIRENZE 293,00 0,00 -

[email protected] [email protected] NUMERI UTILI / / UTILI NUMERI User Numbers User

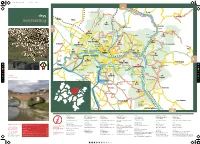

A3-Map-Pontassieve.pdf 1 03/12/19 19:24 ✟ CONVENTO ✟ PIEVE DI S. GIOVANNI MAGGIORE di Bilancino DI BOSCO AI FRATI Villore CAFAGGIOLO Borgo S. Lorenzo BOLOGNA Le Croci di Calenzano Vicchio Map S. Godenzo Pontassieve Agliana PRATO A1 Legri Vaglia CONVENTO Dicomano PISA DI MONTE SENARIO Frascole Rincine Pratolino Contea Calenzano Olmo Acone VILLA DEMIDOFF S. Brigida Cercina Londa A11 Colonnata Scopeti Capalle LA PETRAIA Caldine Sesto Fiorentino CASTELLO Monteloro Pomino Carmignano ✟ PIEVE DI S. BARTOLOMEO Campi Bisenzio AEROPORTO Fiesole Molin del Piano DI FIRENZE Careggi Stia S. Donnino Sieci Signa Pratovecchio Vinci Badia a Settimo FIRENZE Settignano Pontassieve Diacceto FI-PI-LI Castra Pelago Rosano RAVENNA Lastra a Signa Cerreto Guidi ✟ Villamagna Ponte a Cappiano Limite Scandicci Tosi Galluzzo Montemignaio Sovigliana Bagno a Ripoli S. Ellero C Capraia Ponte a Ema Fucecchio Mosciano Certosa Vallombrosa M Grassina S. Croce sull’Arno Rignano sull’Arno ✟ PIEVE Saltino Antella A PITIANA Poppi Y Ginestra Fiorentina S. Donato Empoli in Collina CM Tavarnuzze Chiesanuova Leccio MY Castelfranco di sotto Firenze e torrente Pesa S. Vincenzo a Torri CY Ponte a Elsa Impruneta Area Fiorentina Cerbaia A1 Reggello CMY FI-PI-LI S. Miniato ✟ S. Casciano in Val di Pesa FIRENZE-SIENA PIEVE DI CASCIA K S. Polo in Chianti Baccaiano Montopoli in Val d’Arno Il Ferrone Strada in Chianti Incisa Poppiano Montespertoli Mercatale in Val di Pesa Pian di Scò Cambiano Castelnuovo d’Elsa Cintoia Figline Passo dei Pecorai Palaia Dudda Greve in Chianti Loro Ciuffenna Gaville ✟ PIEVE DI Mura S. ROMOLO S. Giovanni Valdarno Tavarnelle in Val di Pesa AREZZO Terranuova Bracciolini Montaione ✟ Peccioli Certaldo S. -

ALL 9 Rubrica Telefonica

ARI Scandicci Orlandi Stefano Presidente 335393286 ARI Scandicci Leonardo Lastrucci 055741759 3346014967 - 3290579937 ARI Scandicci Sottili Sergio Consigliere 055782021 casa 3334951234 Arpat Arpat reperibilità reperibilità 0557979 Arpat Arpat centralino 05532061 Arpat Arpat fisica ambientale 055320601 Arpat Ing. Piattoli 0553206230 Arpat Ceccanti Maura Responsabile provinciale 0553206272 3280412094 Arpat Dott. Botticelli Sandra Responsabile Controlli-prevenzione 0553206241 Ataf H24 Ataf H24 0555650420 Autorità di Bacino Arno Autorità di Bacino Arno centralino 055267431 05526743-250 Autorità di Bacino Arno Brugioni Marcello Dirigente 05526743220 32886045137/3358378424(pers05526743250 Autorità di Bacino Arno Giovanni Montini sit 05526743226 Autorità di Bacino Arno Mazzanti Bernardo Responsabile SIT 05526743246 Autostrada del sole Sala Radio Direzione IV tronco Autostrade per l'Italia 0554203225-0554203250 Autostrada del sole autor-trasporti eccezionali 0554203283 C.I. Montagna Fiorentina C.I.Montagna Fiorentina Centralino 0558399608 0558397245 C.I. Montagna Fiorentina Dott. Colom Responsabile P.C. 0558396638 C.I. Circondario Empolese Centro Intercomunale Empolese Ufficio Associato P.C. 0571711210 3351985705 05719803333 C.I. Colli Fiorentini CeSi Intercomunale 3346816731 0552593207-255 C.I. Colli Fiorentini UAPC 0552509090 0552593207 C.I. Garfagnana Mauro Giannotti Responsabile P.C. 0583644945 C.I. Mugello C.I.Mugello Ufficio Associato P.C. 0558496283 C.R.I. Firenze Croce Rossa Firenze Centralino Firenze 055215381 C.R.I. Scandicci Pompei -

An Introduction to the Classification of Elasmobranchs

An introduction to the classification of elasmobranchs 17 Rekha J. Nair and P.U Zacharia Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi-682 018 Introduction eyed, stomachless, deep-sea creatures that possess an upper jaw which is fused to its cranium (unlike in sharks). The term Elasmobranchs or chondrichthyans refers to the The great majority of the commercially important species of group of marine organisms with a skeleton made of cartilage. chondrichthyans are elasmobranchs. The latter are named They include sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras. These for their plated gills which communicate to the exterior by organisms are characterised by and differ from their sister 5–7 openings. In total, there are about 869+ extant species group of bony fishes in the characteristics like cartilaginous of elasmobranchs, with about 400+ of those being sharks skeleton, absence of swim bladders and presence of five and the rest skates and rays. Taxonomy is also perhaps to seven pairs of naked gill slits that are not covered by an infamously known for its constant, yet essential, revisions operculum. The chondrichthyans which are placed in Class of the relationships and identity of different organisms. Elasmobranchii are grouped into two main subdivisions Classification of elasmobranchs certainly does not evade this Holocephalii (Chimaeras or ratfishes and elephant fishes) process, and species are sometimes lumped in with other with three families and approximately 37 species inhabiting species, or renamed, or assigned to different families and deep cool waters; and the Elasmobranchii, which is a large, other taxonomic groupings. It is certain, however, that such diverse group (sharks, skates and rays) with representatives revisions will clarify our view of the taxonomy and phylogeny in all types of environments, from fresh waters to the bottom (evolutionary relationships) of elasmobranchs, leading to a of marine trenches and from polar regions to warm tropical better understanding of how these creatures evolved. -

Punti Di Arrivo Puntidipartenza

MERCOLEDI' 25 (orario chiusura viabilità 12:45 - 17:00) Si precisa che nell'intervallo fra due gare successive nello stesso giorno i percorsi gara non vengono riaperti alla circolazione, oltre a questo si ricorda che gli orari di chiusura e la viabilità potranno subire variazioni per cui si consiglia di fare sempre una verifica prima di spostarsi sulle pagine web www.imobi.fi.it Come utilizzare la scacchiera e individuare il proprio percorso: Le varie zone del territorio provinciale sono disposte sia in verticale (punto di partenza) che in orizzontale (punto di arrivo); per identificare il proprio percorso occorre incrociare la riga del punto di partenza con la colonna del punto di arrivo. I percorsi sono individuati tenendo conto che tutte le strade interessate dai percorsi di gara e le limitrofe saranno chiuse. Le zono di Firenze indicate nella scacchiera sono intese come ingressi alla città, per le direttrici di Quartiere consultare la scacchiera del Comune di Firenze ( mondialiciclismo2013.comune.fi.it ) PUNTI DI ARRIVO MUGELLO VALDARNO PIANA FIORENTINA FIESOLE FIRENZE Calenzano - San Borgo Lato Scandicci - Sesto Barberino Lato EMPOLI CHIANTI Donnino San Bagno a Lastra a Fiorentino - Signa Centro Caldine Sud Galluzzo Isolotto Novoli di Mugello Pontassieve (Campi Lorenzo Ripoli Signa Campi Bisenzio) Bisenzio A1 ingresso Barberino di A1 ingresso San Piero a A1 ingresso San Piero a SP8 A1 ingresso A1 ingresso Mugello Barberino di Sieve - A1 ingresso A1 ingresso A1 ingresso Barberino di SP8 Sieve - A1 ingresso Barberinese - Barberino -

1 a Petition to List the Oceanic Whitetip Shark

A Petition to List the Oceanic Whitetip Shark (Carcharhinus longimanus) as an Endangered, or Alternatively as a Threatened, Species Pursuant to the Endangered Species Act and for the Concurrent Designation of Critical Habitat Oceanic whitetip shark (used with permission from Andy Murch/Elasmodiver.com). Submitted to the U.S. Secretary of Commerce acting through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Marine Fisheries Service September 21, 2015 By: Defenders of Wildlife1 535 16th Street, Suite 310 Denver, CO 80202 Phone: (720) 943-0471 (720) 942-0457 [email protected] [email protected] 1 Defenders of Wildlife would like to thank Courtney McVean, a law student at the University of Denver, Sturm college of Law, for her substantial research and work preparing this Petition. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 4 II. GOVERNING PROVISIONS OF THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT ............................................. 5 A. Species and Distinct Population Segments ....................................................................... 5 B. Significant Portion of the Species’ Range ......................................................................... 6 C. Listing Factors ....................................................................................................................... 7 D. 90-Day and 12-Month Findings ........................................................................................ -

DH Lawrence's Travels to Flore

Francesca Pieri ‘This is Tuscany, and Nowhere are the Cypresses so Beautiful and Proud’: D.H. Lawrence’s Travels to Florence, Scandicci and Volterra The aim of this essay is to focus on D.H. Lawrence’s travels to Tuscany, of which he appreciated both its natural beauties and its artistic treasures. In this respect, his private letters bear witness to the author’s feelings and thoughts about this area, which provided proper settings not only for his travel books but also for some of his novels. For instance, in the letters and in some Italian essays, Lawrence often referred to Florence as a beautiful, pleasant city and as such it became the right place for Aaron, the protagonist of Aaron’s Rod (1922), to temporarily live in. The letters also deal with Lawrence’s strong admiration for the Florentine countryside and with his decision in 1926 to move from Florence to Villa Mirenda in Scandicci. From this silent place, in 1927 he set out on a journey to the Etruscan areas of the Maremma coast, visiting Volterra and other cities, as he recorded in Etruscan Places. The Beauties of Tuscany D.H. Lawrence’s strong desire to travel around the world derived not only from his need to free himself from the oppressive conventions of British society, but also from his restless and unstable personality, which led him to continually move from one country to another, always searching for a peaceful and unspoilt place to live. His emotional instability was evident in the way that, during his travels, his initial enthusiasm for discovering new people and cultures was soon followed by a general dissatisfaction with them and by the necessity to change location. -

Ordinary Spaces and Public Life in the City of Fragments Spazi Ordinari E Vita Pubblica Nella Città Di Frammenti

FLORE Repository istituzionale dell'Università degli Studi di Firenze Ordinary Spaces and Public Life in the City of Fragments Questa è la Versione finale referata (Post print/Accepted manuscript) della seguente pubblicazione: Original Citation: Ordinary Spaces and Public Life in the City of Fragments / Giulio Giovannoni. - In: IN BO. - ISSN 2036-1602. - ELETTRONICO. - (2013), pp. 227-248. Availability: This version is available at: 2158/827298 since: Terms of use: Open Access La pubblicazione è resa disponibile sotto le norme e i termini della licenza di deposito, secondo quanto stabilito dalla Policy per l'accesso aperto dell'Università degli Studi di Firenze (https://www.sba.unifi.it/upload/policy-oa-2016-1.pdf) Publisher copyright claim: (Article begins on next page) 27 September 2021 Ricerche e progetti per il territorio, THE PUBLIC SPACE OF EDUCATION la città e l’architettura SPECIAL ISSUE #1/2013 Giulio Giovannoni Tenured researcher at the University of Florence in Urban Planning and Design, former Research Fellow in Urban Studies at the Johns’ Hopkins University. He has been a visiting scholar at UCBerkeley and at Harvard GSD. His current research focuses on suburbs, with a particular interest in international comparisons. Ordinary Spaces and Public Life in the City of Fragments Spazi ordinari e vita pubblica nella città di frammenti The Urban Design Studio held in the fall 2012 within the International Curriculum in Architectural Design at the University of Florence coped with the design of peripheries. These are the least-known parts of Florence but are still the places where most of people live. Here the traditional ideas of the city and of public spaces collapse. -

Florence 102.4 96.4

Table S1: Municipal and investigated areas of the study areas with relative demographic characteristics. Municipal area Investigated area Population density Study‐Areas (km2) (km2) (%) (people per km2) Florence 102.4 96.4 (94.2) 3633.7 Pistoia 236.8 89.5 (37.8) 383.0 Prato 97.6 79.5 (81.4) 1996.4 Scandicci 59.6 45.6 (76.4) 852.2 Lastra a Signa 43.1 43.1 (100.0) 463.8 Bagno a Ripoli 74.0 40.4 (54.7) 345.9 Quarrata 46.0 39.7 (86.3) 581.4 Impruneta 48.7 30.7 (62.9) 299.8 Campi Bisenzio 28.6 28.6 (100.0) 1656.5 Serravalle Pistoiese 42.1 27.6 (65.6) 277.7 Carmignano 38.6 27.6 (71.5) 384.3 Calenzano 76.9 24.5 (31.9) 235.4 Sesto Fiorentino 49.0 23.3 (47.5) 1003.0 Signa 18.8 18.8 (100.0) 1011.8 Montemurlo 30.6 14.9 (48.6) 620.3 Fiesole 42.1 11.9 (28.2) 332.9 Agliana 11.6 11.6 (100.0) 1563.1 Montale 32.1 9.3 (29.0) 336.8 Poggio a Caiano 6.0 6.0 (100.0) 1696.5 Vaiano 34.1 5.9 (17.3) 294.9 Metropolitan area 1118.7 674.9 (60.3) 927.6 Note: investigated area (%) is related to each study‐area. Table S2: Landsat 8 remote sensing data specification of the 2015–2019 period. Sun elevation Sun azimuth Cloud cover Date of acquisition (°) (°) (%) 2015‐06‐06 64.12 136.49 0.28 2015‐07‐24 60.86 136.50 1.16 2015‐08‐09 57.53 140.89 1.76 2016‐06‐24 64.33 134.08 0.17 2016‐07‐10 62.93 134.46 2.12 2016‐08‐27 52.59 147.30 0.32 2017‐06‐11 64.44 135.63 0.13 2017‐07‐29 59.85 137.98 1.88 2017‐08‐30 51.76 148.20 0.07 2018‐06‐30 63.89 133.58 1.47 2018‐08‐17 55.44 143.48 3.41 2019‐06‐17 64.52 134.82 2.43 2019‐07‐19 61.75 135.67 1.75 2019‐08‐20 54.77 144.67 0.04 Table S3: Descriptive statistics of averaged values of LST and UTFVI of the 2015–2019 period for the overall metropolitan area and other municipalities areas. -

Punti Di Arrivo P U N T I D I P a R T E N

SABATO 28 (orario chiusura viabilità 10:30 - 12:30) Si precisa che nell'intervallo fra due gare successive nello stesso giorno i percorsi gara non vengono riaperti alla circolazione, oltre a questo si ricorda che gli orari di chiusura e la viabilità potranno subire variazioni per cui si consiglia di fare sempre una verifica prima di spostarsi sulle pagine web www.imobi.fi.it Come utilizzare la scacchiera e individuare il proprio percorso: Le varie zone del territorio provinciale sono disposte sia in verticale (punto di partenza) che in orizzontale (punto di arrivo); per identificare il proprio percorso occorre incrociare la riga del punto di partenza con la colonna del punto di arrivo. I percorsi sono individuati tenendo conto che tutte le strade interessate dai percorsi di gara e le limitrofe saranno chiuse. Le zono di Firenze indicate nella scacchiera sono intese come ingressi alla città, per le direttrici di Quartiere consultare la scacchiera del Comune di Firenze ( mondialiciclismo2013.comune.fi.it ) PUNTI DI ARRIVO MUGELLO VALDARNO PIANA FIORENTINA FIESOLE FIRENZE Calenzano - San Lato Scandicci - Sesto Barberino Borgo San Lato EMPOLI CHIANTI Donnino Bagno a Lastra a Fiorentino - Signa Centro Caldine Sud Galluzzo Isolotto Novoli di Mugello Lorenzo Pontassieve (Campi Ripoli Signa Campi Bisenzio) Bisenzio SP8 SP8 San Piero a A1 ingresso San Piero a SP8 A1 ingresso A1 ingresso Barberinese - Barberinese - Sieve - A1 ingresso A1 ingresso A1 ingresso Barberino di SP8 Sieve - A1 ingresso Barberinese - Barberino di Barberino di Le Croci Le -

States' Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Laws Hunting, Fishing, and Wildlife

University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture An Agricultural Law Research Project States’ Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Laws Hunting, Fishing, and Wildlife Florida www.NationalAgLawCenter.org States’ Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Laws Hunting, Fishing, and Wildlife STATE OF FLORIDA 68B-44.002 FAC Current through March 28, 2020 68B-44.002 FAC Definitions As used in this rule chapter: (1) “Finned” means one or more fins, including the caudal fin (tail), are no longer naturally attached to the body of the shark. A shark with fins naturally attached, either wholly or partially, is not considered finned. (2) “Shark” means any species of the orders Carcharhiniformes, Lamniformes, Hexanchiformes, Orectolobiformes, Pristiophoriformes, Squaliformes, Squatiniformes, including but not limited to any of the following species or any part thereof: (a) Large coastal species: 1. Blacktip shark -- (Carcharhinus limbatus). 2. Bull shark -- (Carcharhinus leucas). 3. Nurse shark -- (Ginglymostoma cirratum). 4. Spinner shark -- (Carcharhinus brevipinna). (b) Small coastal species: 1. Atlantic sharpnose shark -- (Rhizoprionodon terraenovae). 2. Blacknose shark -- (Carcharhinus acronotus). 3. Bonnethead -- (Sphyrna tiburo). 4. Finetooth shark -- (Carcharhinus isodon). (c) Pelagic species: 1. Blue shark -- (Prionace glauca). 2. Oceanic whitetip shark -- (Carcharhinus longimanus). 3. Porbeagle shark -- (Lamna nasus). 4. Shortfin mako -- (Isurus oxyrinchus). 5. Thresher shark -- (Alopias vulpinus). (d) Smoothhound sharks: 1. Smooth dogfish -- (Mustelus canis). 2. Florida smoothhound (Mustelus norrisi). 3. Gulf smoothhound (Mustelus sinusmexicanus). (e) Atlantic angel shark (Squatina dumeril). (f) Basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus). (g) Bigeye sand tiger (Odontaspis noronhai). (h) Bigeye sixgill shark (Hexanchus nakamurai). (i) Bigeye thresher (Alopias superciliosus). (j) Bignose shark (Carcharhinus altimus). (k) Bluntnose sixgill shark (Hexanchus griseus). (l) Caribbean reef shark (Carcharhinus perezii).