Lawrence Halprin Oral History Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Legacy of a Mad Scientist

i JOHN CARRICK “First, I'd like to know, do any of you have experience in the martial arts?" About half the hands went up. Ashley didn't raise her hand, despite two previous summers of similar courses; she did not count herself as experienced. "Now, how many of you have been hit, hard, in the face?" Sihing Shou asked. At first several hands went up, but some were timid, uncertain. "I mean really hit hard; bloody nose, fat lip, black eye. How many?" Only a few hands remained aloft. Shou pointed to one boy and asked, "Who hit you?" "My brother hits me all the time," he said, pointing at his brother, standing a few spaces away. Shou and several others laughed. Ashley noticed that the boy, however, was not laughing. She suspected he was very interested in how to put a stop his brother’s dominance. "And you?" Shou gestured to another boy. "My father," came the answer. Shou pointed again. "A kid in my class." "Has anyone here ever been hit while in the ring?" Shou asked. All the hands went down. "When you are in a fight, if you are ever in a fight, you must fight for your life. It will be at that moment when you are weak, tired, probably very hurt, that is when you must act to save your life. We will help you get to that place and teach you how to think while you're there." Instructor Shou walked along the front of the room. "Someone may come; an outlaw, the government, a king, they may take all of your possessions. -

"Erase Me": Gary Numan's 1978-80 Recordings

Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture Volume 2 Issue 2 Article 4 June 2021 "Erase Me": Gary Numan's 1978-80 Recordings John Bruni [email protected], [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ought Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Disability Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Bruni, John (2021) ""Erase Me": Gary Numan's 1978-80 Recordings," Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture: Vol. 2 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/ought/vol2/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@GVSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ought: The Journal of Autistic Culture by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@GVSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Erase Me”: Gary Numan’s 1978-80 Recordings John Bruni ary Numan, almost any way you look at him, makes for an unlikely rock star. He simply never fits the archetype: his best album, both Gin terms of artistic and commercial success, The Pleasure Principle (1979), has no guitars on it; his career was brief; and he retired at his peak. Therefore, he has received little critical attention; the only book-length analysis of his work is a slim volume from Paul Sutton (2018), who strains to fit him somehow into the rock canon. With few signposts at hand—and his own open refusal to be a star—writing about Numan is admittedly a challenge. In fact, Numan is a good test case for questioning the traditional belief in the authenticity of individual artistic genius. -

2014 COMMUNITY SURVEY an Assessment by Citizens of Richland’S Strategic Leadership Plan

2014 COMMUNITY SURVEY An assessment by citizens of Richland’s Strategic Leadership Plan. CITY OF RICHLAND 2014 COMMUNITY SURVEY RESULTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report provides an executive summary of the results of Richland’s 2014 Community Survey. The Communications and Marketing Office administered the municipal survey during late 2014. In 2011, a baseline survey was created for the primary purpose of asking residents to assess their level of satisfaction with City Council-identified benchmarks and to obtain input toward potential goals for the Strategic Leadership Plan (SLP). The City conducted the survey in late 2014 so that City Council would receive an analysis of the results prior to its 2015 planning retreat. This timing will allow council to consider residents’ satisfaction levels with current services, suggestions, and comments in establishing the next set of five-year goals for the SLP. This, in turn, will guide the municipal staff in, first, identifying objectives to reach the goals and, second, recommending a budget for future years that will accomplish those objectives. ADMINISTERED BY THE CITY OF RICHLAND, WASHINGTON Communications & Marketing office | 2014 SURVEY METHODOLOGY The City conducted its 2014 survey through a web-based service. The City mailed postcards to a sampling of 4,250 residents, selected at random from the City’s utility customer base, inviting them to participate in the survey and instructing them how to access the survey via the City’s website. The postcard invited recipients without internet access and those who preferred a paper survey to request one by phoning the Communications and Marketing Office. Fifty-five residents requested paper copies of the survey; 45 of those completed and returned their surveys. -

KNV with RADIO UJEH Singles Chart, 10-11; Album Chart, 26; New

WITH M jVll RADIO UJEH 1 ± M. * chart,Singles 26; chart, New 10-11; singles, Album 27; AirplayNorth supplement, guide, 18-19; 20-24. Look 1 [KNV •1' August 18, 1980 VOLUME THREE Number 22 Video producers rebel r Spartan buys at BVA's first meeting disc factory AMID HEATED exchanges, Video consultant Bonnie Molnar SpartanINDEPENDENT Records is spending DISTRIBUTOR in excess of Association,dominance ofbrainchild the new of British the BPI, Video pas- meeting;sparked off"Independent the row when videoshe told com- the plant£200,000 from in buyingMSD andits owninstalling pressing a industrysed rapidly at outlast of week's the hands inaugural of the recordmeet- resentedpanies are on notthe councilbeing properlyand in a newrep- computer-controlled sales and stock sys- A furious row over membership of the industrythe BVA they to shouldend up be. like We thedon't BPI want - Wembley-basedThe move is designedcompany to makevirtually the BVA council erupted when plans were dominated by the major companies." THESEenough toDAYS come goldby - discsbut gold are chairs hard self-sufficient for its labels' pressing revealedthe council for tofive be offilled the bytwelve record scats com- on agingAnd director,Mike Tenner, commented: Intervision "We man- are are something else. Joan Armatrading steprequirements it has taken and since is seen it was as formedthe biggest two pany executives for the next three years. grateful for the work done so far by the presentedis snapped with in thethe verypiece act of furnitureof being years ago. wouldIt was be proposed automatically that thesetaken five by seatsCBS recordbe more companies, enthusiastic but abouteveryone the wouldBVA that appeared on the front cover of her plantSpartan on hasthe boughtTrecenydd Ian Miles'Industrial ISS chairman, Maurice Oberslein, who council if it represented the whole video Myself,recently-certified I by A&M goldmen (leftalbum to right)Me, Estate at Caerphilly, Glamorgan. -

Tubeway Army Torrent

1 / 2 Tubeway Army Torrent Download via torrent: Categoria bittorrent, Musica. Descrizione. Artist. ... Are 'Friends' Electric - Tubeway Army 3. Temptation .... Index of /music/Gary Numan + Tubeway Army/Replicas (Full Album) [320kbps.MP3] ... Gary Numan + Tubeway Army - Replicas.torrent, 31-Aug-2016 12:30, 3.8K .... BEGA 150 CD. Producer · Gary Numan, Dramatis, Simon Heywood, Kenny Denton. Gary Numan / Tubeway Army chronology .... ... the machman, the pleasure principle, trent reznor, tubeway army, ... the restricted movements of the first half giving way to the torrent of .... Tubeway Army and Gary Numan Discography with Information ... www.numandiscography.co.uk. Search only this Tubeway Army | Gary Numan Discography: Gary Numan Diaries: Next Announced Live ... gary numan discography torrent.. The two Tubeway Army LPs (self-titled debut & Replicas) are an odd pairing. Gary was just writing punk ... that one is hard to get. Only torrent:( .... TrondheimSolistene - Divertimenti 2008 (SACD-ISO). Tsai Chin - Folk Songs (1996) [Reissue 2004] (SACD-ISO). Tubeway Army - Replicas (2008 Release) (24 .... Size: 202 MB Torrent Contents • Gary Numan & Tubeway Army • Replicas Early Versions • 2-01 Me! I Disconnect From You.mp3 4,785 KB .... Tubeway Army 10 I Don't Like Mondays. The Boomtown Rats 11 We Don't Talk Anymore. Cliff Richard 12 Cars. Gary Numan 13 Message In A ... Download Gary Numan & Tubeway Army - Discography (Re-up) (1978-2019) (320) [DJ] torrent or any other torrent from Music category.. Download Tubeway Army Torrents absolutely for free, Magnet Link And Direct Download also Available.. Télécharger, Télécharger le torrent. Mots clés, Mp3 Cd ... Oliverís Army - Elvis Costello & The Attractions 509. ... Gary Numan & Tubeway Army 513. -

Gary Numan and Tubeway Army

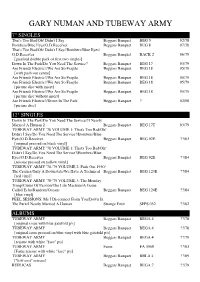

GARY NUMAN AND TUBEWAY ARMY 7" SINGLES That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say Beggars Banquet BEG 5 02/78 Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 8 07/78 That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say//Bombers/Blue Eyes/ O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BACK 2 06/79 [gatefold double pack of first two singles] Down In The Park/Do You Need The Service? Beggars Banquet BEG 17 03/79 Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [with push-out centre] Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [picture disc with insert] Are Friends Electric?/We Are So Fragile Beggars Banquet BEG 18 05/79 [picture disc without insert] Are Friends Electric?/Down In The Park Beggars Banquet ? 02/08 [picture disc] 12" SINGLES Down In The Park/Do You Need The Service?/I Nearly Married A Human 2 Beggars Banquet BEG 17T 03/79 TUBEWAY ARMY '78 VOLUME 1: That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say/Do You Need The Service?/Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 92E ??/83 [original pressed on black vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78 VOLUME 1: That's Too Bad/Oh! Didn't I Say/Do You Need The Service?/Bombers/Blue Eyes/O.D.Receiver Beggars Banquet BEG 92E ??/84 [reissue pressed on yellow vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78-'79 VOLUME 2: Fade Out 1930/ The Crazies/Only A Downstate/We Have A Technical Beggars Banquet BEG 123E ??/84 [red vinyl] TUBEWAY ARMY '78-'79 VOLUME 3: The Monday Troop/Crime Of Passion/The Life Machine/A Game Called Echo/Random/Oceans Beggars Banquet BEG 124E ??/84 [blue -

Sing! 1975 – 2014 Song Index

Sing! 1975 – 2014 song index Song Title Composer/s Publication Year/s First line of song 24 Robbers Peter Butler 1993 Not last night but the night before ... 59th St. Bridge Song [Feelin' Groovy], The Paul Simon 1977, 1985 Slow down, you move too fast, you got to make the morning last … A Beautiful Morning Felix Cavaliere & Eddie Brigati 2010 It's a beautiful morning… A Canine Christmas Concerto Traditional/May Kay Beall 2009 On the first day of Christmas my true love gave to me… A Long Straight Line G Porter & T Curtan 2006 Jack put down his lister shears to join the welders and engineers A New Day is Dawning James Masden 2012 The first rays of sun touch the ocean, the golden rays of sun touch the sea. A Wallaby in My Garden Matthew Hindson 2007 There's a wallaby in my garden… A Whole New World (Aladdin's Theme) Words by Tim Rice & music by Alan Menken 2006 I can show you the world. A Wombat on a Surfboard Louise Perdana 2014 I was sitting on the beach one day when I saw a funny figure heading my way. A.E.I.O.U. Brian Fitzgerald, additional words by Lorraine Milne 1990 I can't make my mind up- I don't know what to do. Aba Daba Honeymoon Arthur Fields & Walter Donaldson 2000 "Aba daba ... -" said the chimpie to the monk. ABC Freddie Perren, Alphonso Mizell, Berry Gordy & Deke Richards 2003 You went to school to learn girl, things you never, never knew before. Abiyoyo Traditional Bantu 1994 Abiyoyo .. -

White Wolf Npcs

VOLUME 3: KINDRED AND RELATED Assamites ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Ahmed ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 Al-Ashrad (Amr of Alamut) ......................................................................................................................... 4 Coven, Montgomery (Once and Forever Prince) ............................................................................................. 5 Djuhah (Seraph of the Black Hand) ............................................................................................................ 6 al-Faqadi, Fatima (Hand of Vengeance) ........................................................................................................ 8 Izhim Ur-Baal (Seraph of the Black Hand) ................................................................................................... 8 Osiris (Unbound Bodyguard) ....................................................................................................................... 9 Solinda (Chicago Bishop and Dominion) ....................................................................................................... 9 Tariq the Silent (1996 Onward, Dominion) .................................................................................................. 10 Ur-Shulgi (The Shepherd) ........................................................................................................................ -

2 Column Indented

22,000 Karaoke Songs - AMS Entertainment ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years Duck And Run 6188 Through The Iris 20005 Here By Me 17629 Wasteland 16042 Here Without You 13010 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 17630 10,000 Maniacs Kryptonite 6190 Because The Night 1750 Landing In London 17631 Candy Everybody Wants 2621 Let Me Be Myself 25227 Like The Weather 16149 Let Me Go 13785 More Than This 16150 Live For Today 13648 These Are The Days 1273 Loser 6192 Trouble Me 16151 Road I'm On, The 6193 So I Need You 17632 10cc When I'm Gone 13086 Donna 20006 Dreadlock Holiday 11163 30 Seconds To Mars I'm Mandy 16152 Kill, The (Bury Me) 16155 I'm Not In Love 2631 Rubber Bullets 20007 311 Things We Do For Love, The 10788 All Mixed Up 16156 Wall Street Shuffle 20008 Don't Tread On Me 13649 First Straw 22322 112 Love Song 22323 Come See Me 25019 You Wouldn't Believe 22324 Dance With Me 22319 It's Over Now 22320 38 Special Peaches & Cream 22321 Caught Up In You 1904 U Already Know 13602 Hold On Loosely 1901 Second Chance 17633 2 Tons O' Fun Teacher, Teacher 13492 It's Raining Men (Hallelujah!) 6017 3LW 2 Unlimited No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 11795 No Limits 6183 3Oh!3 20 Fingers Don't Trust Me 16157 Short Dick Man 1962 3OH!3 & Katy Perry 2Pac Starstrukk 25138 California Love (Original Version) 14147 Changes 12761 4 Him Ghetto Gospel 16153 Basics Of Life 20002 For Future Generations 20003 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

Beyond the Brass Plaque: Reinterpreting Rock Creek

BEYOND THE BRASS PLAQUE: REINTERPRETING ROCK CREEK PARK by MELISSA ANNE KNAUER (Under the Direction of Marianne Cramer) ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of an urban, wilderness park, the National Park Service’s Rock Creek Park in Washington, DC and the ways this park is interpreted. The first part of this thesis discusses landscape interpretation in general and specifically investigates the manifestation of interpretation in Rock Creek Park. It analyzes and discusses the existing interpretation methods the National Park Service uses in the park. Next, it explores new or different methods of interpreting by examining related examples, from art installations, other landscape architecture projects, museum exhibits and land art, that help to expand traditional interpretation. Finally, using the broader ideas about interpretation, it develops schematic design examples of new and creative ways to reinterpret Rock Creek Park. The end goal of this thesis is to develop new methods of interpretation in hopes of reaching more of the variety of users in the Park, giving them a broader understanding of the Park and its resources. INDEX WORDS: Interpretation, Rock Creek Park, National Park Service, Urban Parks BEYOND THE BRASS PLAQUE: REINTERPRETING ROCK CREEK PARK by MELISSA ANNE KNAUER B.A., Randolph-Macon Woman’s College, 1992 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE ATHENS, GEORGIA 2004 © 2004 Melissa A. Knauer All Rights Reserved BEYOND THE BRASS PLAQUE: REINTERPRETING ROCK CREEK PARK by MELISSA ANNE KNAUER Major Professor: Marianne Cramer Committee: Brian LaHaie Carter Betz Ian Firth Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2004 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Thomas Rainer, my fiancé. -

Gary Numan Numanme

ISSUE SIX NUMANME £0.00 GARY NUMAN THE GARY NUMAN FAN SITE MAGAZINE Numanme Magazine issue 6 CONTENTS Lyric from the past - page 4 An Englishman Abroad - Smash Hits, September 2 - 15, 1982 page 5 (thanks to Jim Lester for the scan) James Freud - Breaks Silence on the Numan Case - James Freud interview - Juke Magazine (1980) page 12 Well, would YOU go up in a plane with Gary Numan? - Daily Mirror, Mon. Feb 8th 1982 page 17 Gary's A Nu-Man Now - Interview - Patches Magazine, 1979 page 22 Numan Goes in to space - NME 29/09/79 by Glenn Gibson page 24 2 Numanme Magazine issue 6 www.numanme.co.uk EDITOR: Richard Churchward email: [email protected] YOUR HELP: If you have clippings or pictures or any articles, stories about you as a fan, or any upcoming events, just send them in and you could have them published, full credit will be given. Please give as much information as possible this will save time. email: [email protected] TEXT RIPPED BY COMPUTER: All archive articles are from the Numanme scrapbook and clippings vaults. The Numanme Gary Numan Magazine is a glossy, full colour, 20 pages plus, PDF file. This publication comes out 3 to 4 times a year, time willing! The Gary Numan Magazine is packed with fascinating and thoroughly researched articles on all aspects of Gary Numan’s career, past and present. We delve into the vaults of Numanme to find old articles and clippings. And give you an insight into Gary’s career seen through the eyes of fans all around the world.