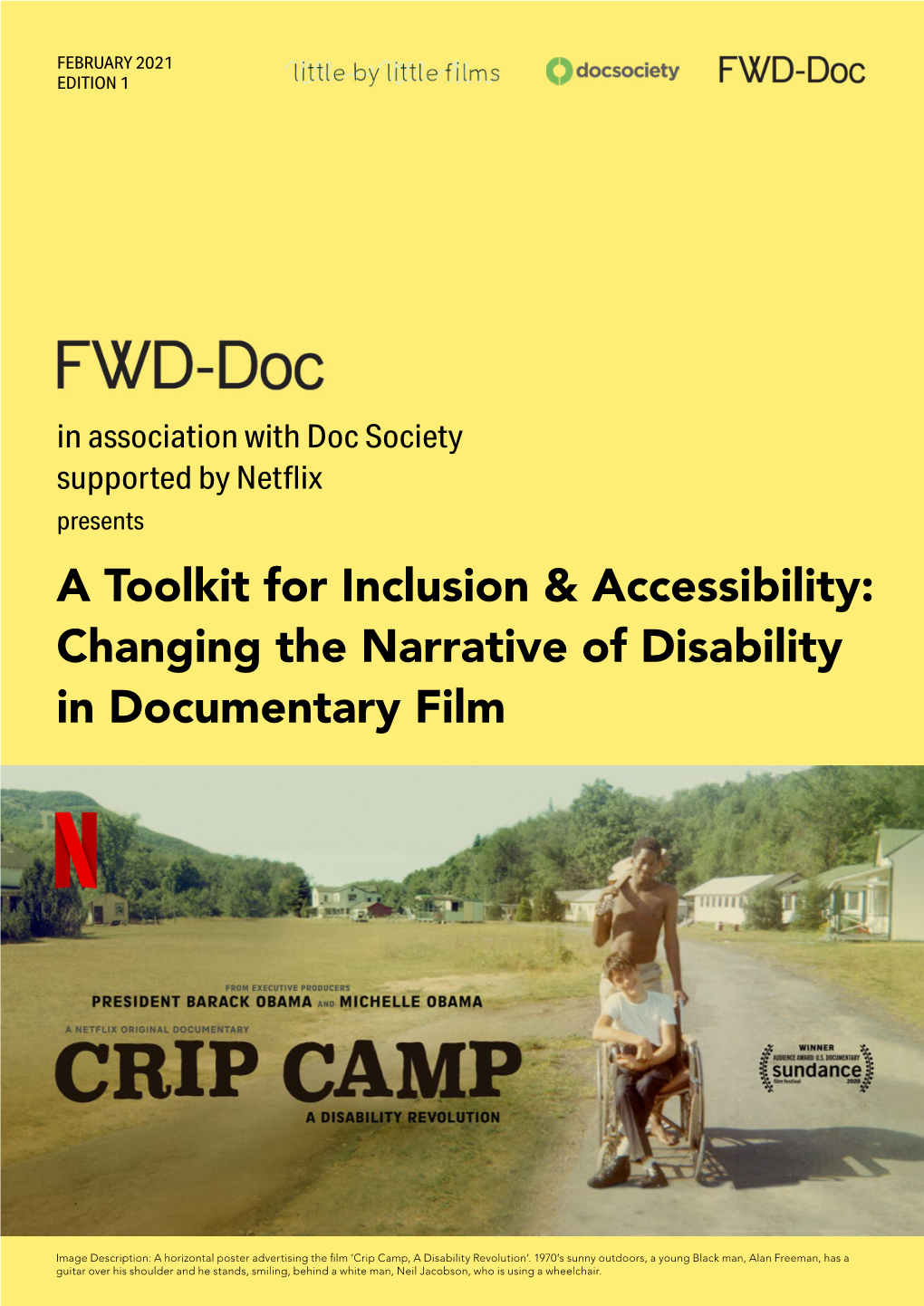

A Toolkit for Inclusion & Accessibility: Changing the Narrative of Disability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daft Punk Collectible Sales Skyrocket After Breakup: 'I Could've Made

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayFEBRUARY 25, 2021 Page 1 of 37 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Daft Punk Collectible Sales Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debutsSkyrocket at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience After impressions, Breakup: up 16%). Top Country• Spotify Albums Takes onchart dated April 18. In its first week (ending April 9), it earned$1.3B 46,000 in equivalentDebt album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cording• Taylor to Nielsen Swift Music/MRCFiles Data. ‘I Could’veand total Made Country Airplay No.$100,000’ 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideHer Own marks Lawsuit Hunt’s in second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chartEscalating and fourth Theme top 10. It follows freshman LP BY STEVE KNOPPER Young’s first of six chart entries, “Sleep With- MontevalloPark, which Battle arrived at the summit in No - out You,” reached No. 2 in December 2016. He vember 2014 and reigned for nine weeks. To date, followed with the multiweek No. 1s “In Case You In the 24 hours following Daft Punk’s breakup Thomas, who figured out how to build the helmets Montevallo• Mumford has andearned Sons’ 3.9 million units, with 1.4 Didn’t Know” (two weeks, June 2017), “Like I Loved millionBen in Lovettalbum sales. -

Intersectionality and the Disability Rights Movement: the Black Panthers, the Butterfly Brigade, and the United Farm Workers of America

JW Marriott Austin, Texas July 19-23, 2021 Intersectionality and the Disability Rights Movement: The Black Panthers, the Butterfly Brigade, and the United Farm Workers of America Paul Grossman, J.D., P.A. Mary Lee Vance, Ph.D. Jamie Axelrod, M.S. JW Marriott Austin, Texas July 19-23, 2021 Faculty Grossman, Axelrod and Vance Consulting, Beyond the ADA Paul Grossman, J.D., P.A. US, ED, OCR, Chief Regional Civil Rights Attorney, SF, retired Guest Lecturer for Disability Law, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Hastings and Berkeley Colleges of Law, U.C. NAADAC, OCR DisNet, & CAPED Faculty Member Former AHEAD Board Member; Blosser Awardee AHEAD and CHADD Public Policy Committees Member The Law of Disability Discrimination for Higher Education Professionals, Carolina Academic Press (updated annually) JW Marriott Austin, Texas July 19-23, 2021 Faculty Grossman, Axelrod and Vance Consulting, Beyond the ADA Jamie Axelrod, M.S. Mary Lee Vance, Ph.D. Dir., Disability Resources, Northern Arizona University Dir., Services for Students with Disabilities, Sacramento State University ADA Coordinator/Section 504 Compliance Officer, Northern Arizona Former AHEAD Bd. Member; University Member, JPED Editorial Bd.; Immediate Past President AHEAD Board Member, Coalition for Disability Reviewer, NACADA National Advising Journal Access in Health Science and Education Co-editor, Beyond the ADA (NASPA 2014) Member AHEAD Public Policy Committee JW Marriott Austin, Texas July 19-23, 2021 Caveat This presentation and its associated materials are provided for informational purposes only and are not to be construed as legal advice. You should seek your Systemwide or house counsel to resolve the individualized legal issues that you are responsible for addressing. -

Beyond Diversity and Inclusion: Understanding and Addressing Ableism, Heterosexism, and Transmisia in the Legal Profession: Comm

American Journal of Law & Medicine, 47 (2021): 76-87 © 2021 The Author(s) DOI: 10.1017/amj.2021.3 Beyond Diversity and Inclusion: Understanding and Addressing Ableism, Heterosexism, and Transmisia in the Legal Profession: Comment on Blanck, Hyseni, and Altunkol Wise’s National Study of the Legal Profession Shain A. M. Neumeier† and Lydia X. Z. Brown†† I. INTRODUCTION Far too many—if not most—of us in the legal profession who belong to both the disability and LGBTQþ communities have known informally, through our own experi- ences and those of others like us, that workplace bias and discrimination on the basis of disability, sexuality, and gender identity is still widespread. The new study by Blanck et al. on diversity and inclusion in the U.S. legal profession provides empirical proof of this phenomenon, which might otherwise be dismissed as being based on anecdotal evidence.1 Its findings lend credibility to our position that the legal profession must make systemic changes to address workplace ableism, heterosexism, and transmisia.2 They also suggest †Committee for Public Counsel Services, Mental Health Litigation Division. (The contents of this article are published in the author’s personal capacity.) ††Georgetown University, Disability Studies Program, [email protected]. With thanks to Sara M. Acevedo Espinal, Jennifer Scuro, and Jess L. Cowing for support. 1Peter Blanck, Fitore Hyseni & Fatma Artunkol Wise, Diversity and Inclusion in the American Legal Profession: Discrimination and Bias Reported by Lawyers with Disabilities and Lawyers Who Identify as LGBTQþ,47Am. J.L. & Med. 9, 9 (2021) [hereinafter Blanck, et al., Discrimination and Bias]. -

Guidelines for Inclusion: Ensuring Access to Education for All Acknowledgments

Guidelines for Inclusion: Ensuring Access to Education for All Acknowledgments In UNESCO’s efforts to assist countries in making National Plans for Education more inclusive, we recognised the lack of guidelines to assist in this important process. As such, the Inclusive Education Team, began an exercise to develop these much needed tools. The elaboration of this manual has been a learning experience in itself. A dialogue with stakeholders was initiated in the early stages of elaboration of this document. “Guidelines for Inclusion: Ensuring Access to Education for All”, therefore, is the result of constructive and valuable feedback as well as critical insight from the following individuals: Anupam Ahuja, Mel Ainscow, Alphonsine Bouya-Aka Blet, Marlene Cruz, Kenneth Eklindh, Windyz Ferreira, Richard Halperin, Henricus Heijnen, Ngo Thu Huong, Hassan Keynan, Sohae Lee, Chu Shiu-Kee, Ragnhild Meisfjord, Darlene Perner, Abby Riddell, Sheldon Shaeffer, Noala Skinner, Sandy Taut, Jill Van den Brule-Balescut, Roselyn Wabuge Mwangi, Jamie Williams, Siri Wormnæs and Penelope Price. Published in 2005 by the United Nations Educational, Scientifi c and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy, 75352 PARIS 07 SP Composed and printed in the workshops of UNESCO © UNESCO 2005 Printed in France (ED-2004/WS/39 cld 17402) Foreward his report has gone through an external and internal peer review process, which targeted a broad range of stakeholders including within the Education Sector at UNESCO headquarters and in the fi eld, Internal Oversight Service (IOS) and Bu- Treau of Strategic Planning (BSP). These guidelines were also piloted at a Regional Work- shop on Inclusive Education in Bangkok. -

Scaffolding Inquiry-Based Science and Chemistry Education in Inclusive Classrooms

In: New Developments in Science Education Research ISBN: 978-1-63463-914-9 Editor: Nathan L. Yates © 2015 Nova Science Publishers, Inc. Chapter 5 SCAFFOLDING INQUIRY-BASED SCIENCE AND CHEMISTRY EDUCATION IN INCLUSIVE CLASSROOMS Simone Abels University of Vienna, Austrian Educational Competence Centre Chemistry, Vienna, Austria ABSTRACT Since the ratification of the UN Convention on Rights of Persons with Disabilities inclusion is on the agenda. In science education inquiry-based learning is, among others, recommended to deal with the diversity of students in a classroom. However, teachers struggle with the implementation of inquiry-based science education and view heterogeneity rather as a burden than an asset. Therefore, this research project is dedicated to the teachers‘ scaffolding teaching science in inclusive classes. Specifically, within the framework of a qualitative case study, the focus lies upon inquiry-based learning environments with different levels of openness and structuring and how they can be orchestrated to deal with diverse learning needs of all students in one classroom. The research study is conducted in cooperation with an inclusive urban middle school (grade 5 to 8), where students with and without special educational needs learn together. Initially, the article introduces the inclusive school with its specific way and challenges – not only the science classes – as inclusion is holistic school development. Subsequently, two science formats are particularly focused and contrasted: guided inquiry-based chemistry lessons as well as the format Lernwerkstatt (German for workshop center), an open inquiry setting. The aim of the Lernwerkstatt is that students work self-dependently on their own scientific questions innervated by carefully arranged phenomena and materials. -

Performing the Fractured Puppet Self

Performing the Fractured Puppet Self Employing auto-ethnopuppetry to portray and challenge cultural and personal constructions of the disabled body by Emma C. Fisher Supervisor: Doctor Michael Finneran A thesis submitted for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Drama and Theatre Studies Mary Immaculate College (Coláiste Mhuire Gan Smál) University of Limerick Ph.D. ABSTRACT This research project examines personal and cultural constructs of the disabled body, with the creation of the puppet play Pupa as its practical culmination. The testimonials of six participants (including my own), all from artists with a disability or deaf artists, are the inspiration for Pupa. The qualitative research methodology used within this research combines ethnographic methods, auto-ethnography, practice-based research and narrative enquiry. I have adapted auto-ethnography by combining it with puppetry to coin new methodologies; ‘ethnopuppetry’ and ‘auto-ethnopuppetry’. Inspired by fairytales, Pupa creates a fantastical world where the narratives of the participants find expression through a range of puppet characters. These testimonies examine what it is to identify with a disabled identity, and to ‘come out’ as disabled. It looks at how we perceive ourselves as disabled, and how we feel others perceive us. Creating a piece of theatre based around disabled identity led me to investigate the history of disabled performers, and historical depictions of disabled characters within theatre, fairytales and freak-shows, in order to see how they influence societal beliefs around disability today. Within the practice element of this research, I experimented with unconventionally constructed puppets, as well as puppeteering my own disabled limb with an exo-skeleton, in order to question how I view disability in my own body. -

Eliminating Ableism in Education

Eliminating Ableism in Education THOMAS HEHIR Harvard Graduate School of Education In this article, Thomas Hehir defines ableism as “the devaluation of disability” that “results in societal attitudes that uncritically assert that it is better for a child to walk than roll, speak than sign, read print than read Braille, spell independently than use a spell-check, and hang out with nondisabled kids as opposed to other dis- abled kids.” Hehir highlights ableist practices through a discussion of the history of and research pertaining to the education of deaf students, students who are blind or visually impaired, and students with learning disabilities, particularly dyslexia. He asserts that “the pervasiveness of...ableistassumptionsintheeducationof children with disabilities not only reinforces prevailing prejudices against disability but may very well contribute to low levels of educational attainment and employ- ment.” In conclusion, Hehir offers six detailed proposals for beginning to address and overturn ableist practices. Throughout this article, Hehir draws on his per- sonal experiences as former director of the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Special Education Programs, Associate Superintendent for the Chicago Public Schools, and Director of Special Education in the Boston Public Schools. Ableist Assumptions When Joe Ford was born in 1983, it was clear to the doctors and to Joe’s mom Penny that he would likely have disabilities. What wasn’t clear to Penny at the time was that she was entering a new world, that of a parent of a child with disabilities, a world in which she would have to fight constantly for her child to have the most basic of rights, a world in which deeply held negative cul- tural assumptions concerning disability would influence every aspect of her son’s life. -

Inquiring Minds Want to Know: Inquiry-Based Learning in the General Education and Inclusion Science Classroom

129 Inquiring Minds Want to Know: Inquiry-Based Learning in the General Education and Inclusion Science Classroom Gena M. Rosenzweig, Maria Carrodegaus, and Luretha Lucky Florida International University, USA Abstract: This study sought to apply the concepts of inquiry-based learning by increasing the number of laboratory experiments conducted in two science classes, and to identify the challenges of this instruction for students with special needs. Results showed that the grades achieved through lab write-ups greatly improved grades overall. The National Science Education Standards (1996) describes inquiry-based instruction as a way to involve students in a form of active learning that emphasizes questioning, data analysis, and critical thinking. This teaching practice encourages students to learn inductively and has a firmly established place in pedagogical tradition (Colburn, 2004). For example, theorists Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and Herbert Spencer have championed student learning through concrete experiences and observations rather than rote memorization. Students at all grade levels, in every domain of science education, should be afforded the opportunity to use scientific inquiry to develop the ability to think and act in ways that are associated with inquiry (Bell, Smetana, & Binns, 2005). A convenient way to accomplish this goal in middle school classrooms is to enhance the inquiry aspects of activities that are already incorporated into the curriculum (Godbey, Barnett, & Webster, 2005). Teachers are challenged to effectively use inquiry-based learning strategies to motivate and teach students, particularly those in a special education curriculum. When properly introduced, inquiry-based activities increase student interest and motivation. The student becomes a fellow investigator, with motivation shifting from an extrinsic desire for a higher grade to an intrinsic one for satiating a curiosity of nature (Baker, Lang, & Lawson, 2002). -

Guidelines: How to Write About People with Disabilities

Guidelines: How to Write about People with Disabilities 9th Edition (On the Cover) Deb Young with her granddaughters. Deb is a triple amputee who uses a power (motorized) wheelchair. Online You can view this information online at our website. You can also download a quick tips poster version or download the full pdf of the Guidelines at http://rtcil.org/sites/rtcil.drupal.ku.edu/files/ files/9thguidelines.jpg Guidelines: How to Write about People with Disabilities You can contribute to a positive image of people with disabilities by following these guidelines. Your rejection of stereotypical, outdated language and use of respectful terms will help to promote a more objective and honest image. Say this Instead of How should I describe you or your disability? What are you? What happened to you? Disability Differently abled, challenged People with disabilities, disabled Handicapped Survivor Victim, suffers from Uses a wheelchair, wheelchair user Confined to a wheelchair Service dog or service animal Seeing eye dog Accessible parking or restroom Handicapped parking, disabled stall Person with Down syndrome Mongoloid Intellectual disability Mentally retarded, mental retardation Autistic, on the autism spectrum, atypical Abnormal Deb Young with her granddaughters. Deb is a triple amputee who uses a power Person with a brain injury Brain damaged motorized) wheelchair. Person of short stature, little person Midget, dwarf For More Information Person with a learning disability Slow learner, retard Download our brochure, Guidelines: How Person with -

35 Years of Nominees and Winners 36

3635 Years of Nominees and Winners 2021 Nominees (Winners in bold) BEST FEATURE JOHN CASSAVETES AWARD BEST MALE LEAD (Award given to the producer) (Award given to the best feature made for under *RIZ AHMED - Sound of Metal $500,000; award given to the writer, director, *NOMADLAND and producer) CHADWICK BOSEMAN - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom PRODUCERS: Mollye Asher, Dan Janvey, ADARSH GOURAV - The White Tiger Frances McDormand, Peter Spears, Chloé Zhao *RESIDUE WRITER/DIRECTOR: Merawi Gerima ROB MORGAN - Bull FIRST COW PRODUCERS: Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, THE KILLING OF TWO LOVERS STEVEN YEUN - Minari Anish Savjani WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Robert Machoian PRODUCERS: Scott Christopherson, BEST SUPPORTING FEMALE MA RAINEY’S BLACK BOTTOM Clayne Crawford PRODUCERS: Todd Black, Denzel Washington, *YUH-JUNG YOUN - Minari Dany Wolf LA LEYENDA NEGRA ALEXIS CHIKAEZE - Miss Juneteenth WRITER/DIRECTOR: Patricia Vidal Delgado MINARI YERI HAN - Minari PRODUCERS: Alicia Herder, Marcel Perez PRODUCERS: Dede Gardner, Jeremy Kleiner, VALERIE MAHAFFEY - French Exit Christina Oh LINGUA FRANCA WRITER/DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Isabel Sandoval TALIA RYDER - Never Rarely Sometimes Always NEVER RARELY SOMETIMES ALWAYS PRODUCERS: Darlene Catly Malimas, Jhett Tolentino, PRODUCERS: Sara Murphy, Adele Romanski Carlo Velayo BEST SUPPORTING MALE BEST FIRST FEATURE SAINT FRANCES *PAUL RACI - Sound of Metal (Award given to the director and producer) DIRECTOR/PRODUCER: Alex Thompson COLMAN DOMINGO - Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom WRITER: Kelly O’Sullivan *SOUND OF METAL ORION LEE - First -

Did a Summer Camp Help Spark a Disability Revolution? Transcript

THE LAURA FLANDERS SHOW DID A SUMMER CAMP HELP SPARK A DISABILITY REVOLUTION? LAURA FLANDERS: What can a small pocket of inclusive culture make possible for people who are normally marginalized or excluded from mainstream society? Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution is a Peabody award-winning documentary from Netflix and Higher Ground Productions that tells the story of Camp Jened, a summer camp in Upstate New York in the 1960s where disabled young people could be themselves. The film follows former campers into their adulthoods as activists whose work during the '70s and '80s helped secure federal civil rights for disabled people and eventually led to the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990. But the story doesn't end there, the disability rights movement, like so many movements in American history, prioritized at first the leadership visibility and needs mostly of white straight cis-gender disabled people. Recognizing this, the directors and producers of Crip Camp are using their film's release to educate audiences about the next step in the revolution, disability justice. That movement centers the leadership of disabled queer, trans, Black, Indigenous and people of color. If the inclusive culture of Camp Jened could help transform American society in the second half of the 20th century they ask, what could a truly intersectional disability justice movement change for everyone today? Joining me are co-producers and co-directors of Crip Camp: A Disability Revolution, Jim LeBrecht and Nicole Newnham. And Andraéa LaVant, she's chief inclusion officer of LaVant Consulting, Inc. I'd like to begin first with congratulating you all for the Peabody award, which was announced this June. -

Une Issue Grâce À La Pandémie ? La Covid-19 Ne Fait Pas Que Fermer Des Portes

woxx déi aner wochenzeitung l’autre hebdomadaire 1574/20 ISSN 2354-4597 2.50 € 03.04.2020 Une issue grâce à la pandémie ? La Covid-19 ne fait pas que fermer des portes. Avec les mesures prises pour les toxicomanes, certain-e-s pourraient sortir plus facilement de leur dépendance qu’avant. Regards p. 4 EDITO NEWS REGARDS 0 1 5 7 4 Wer ist hier ein Virus? S. 2 Gesundheit und Sicherheit gehen vor S. 3 Grenzen digitalen Lernens S. 6 Die Covid-19-Krise ruft sehr fragewürdige In Bezug auf die Änderungen des Arbeits- Von einem Tag auf den anderen mussten ökologische Diskussionen hervor, rechts wegen der Coronakrise wird die Bildungsinstitutionen auf Fernlehre die zu einem gefährlichen Diskurs befürchtet, dass Arbeitnehmer*innen- umsteigen. Manche Betroffene kommen 5 453000 211009 führen könnten. rechte beschnitten werden. damit besser zurecht als andere. 2 NEWS woxx | 03 04 2020 | Nr 1574 EDITORIAL Covid-19 uNd Ökologie NEWS Das wahre Virus Joël Adami Sind wir Menschen ein Virus, das die Menschen, die ihn verbreiten, sich den Planeten bedroht, und Covid-19 vermutlich um unsere natürliche Um- die Rache der Natur? Solche Ideen welt sorgen, liegt diesem Gedanken sind nicht nur unsinnig, sondern paradoxerweise ein äußerst anthro- richtig gefährlich. pozentrisches Weltbild zugrunde: Die Menschheit und die Natur als sich In vielen Ländern der Welt be- bekämpfende Gegenspielerinnen, die stehen derzeit Ausgangsverbote, die nichts miteinander zu tun haben. wirtschaftliche Aktivität wird auf ein Dabei verhält sich die Sache ganz Minimum zurückgefahren. Das hat anders. selbstverständlich auch Auswirkun- Das Virus ist überhaupt nur des- gen auf die natürliche Umwelt.