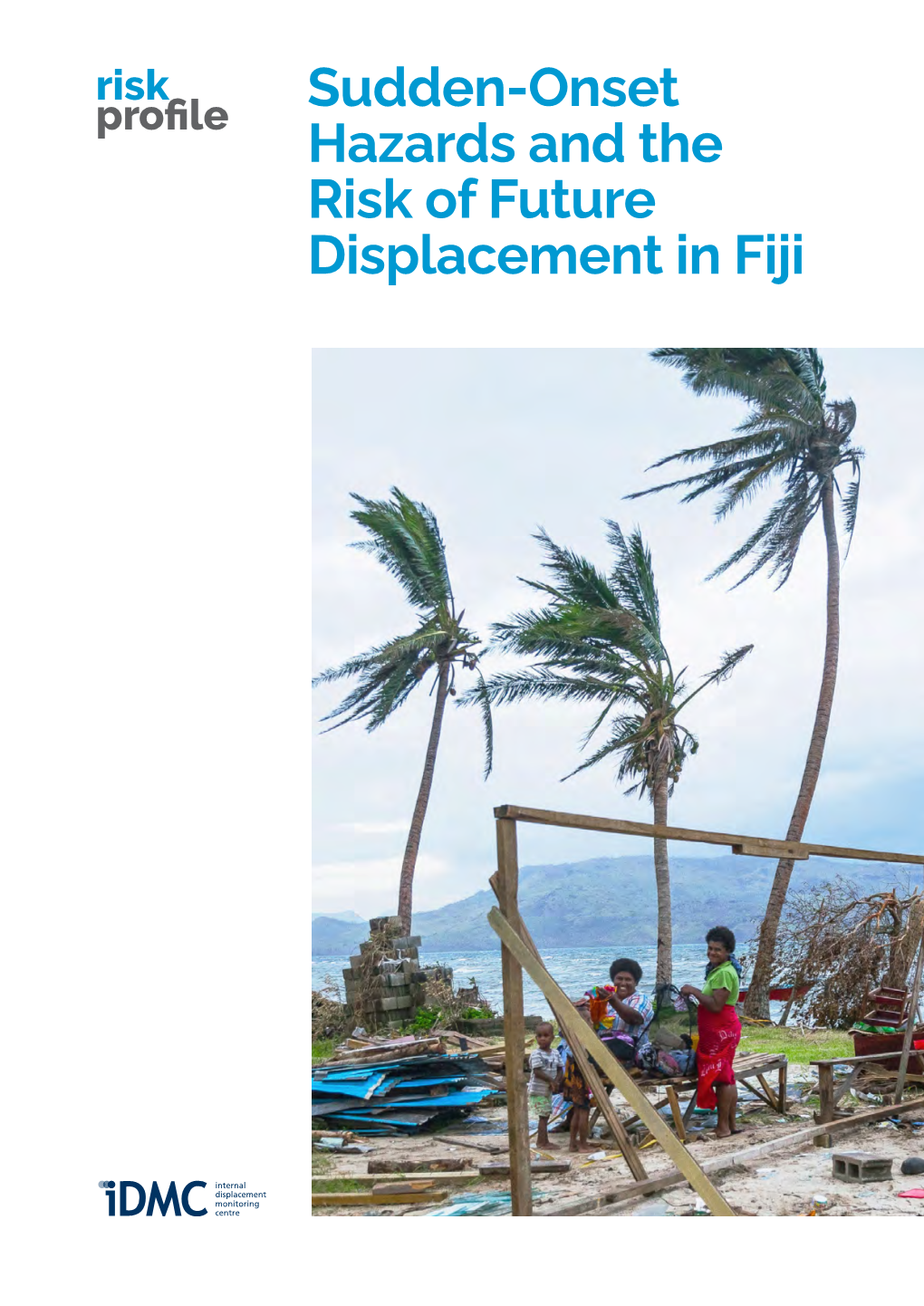

Fiji Cyclone Evan, Fiji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cyclone Factsheet UPDATE

TROPICAL CYCLONES AND CLIMATE CHANGE: FACTSHEET CLIMATECOUNCIL.ORG.AU TROPICAL CYCLONES AND CLIMATE CHANGE: FACT SHEET KEY POINTS • Climate change is increasing the destructive power of tropical cyclones. o All weather events today, including tropical cyclones, are occurring in an atmosphere that is warmer, wetter, and more energetic than in the past. o It is likely that maximum windspeeds and the amount of rainfall associated with tropical cyclones is increasing. o Climate change may also be affecting many other aspects of tropical cyclone formation and behaviour, including the speed at which they intensify, the speed at which a system moves (known as translation speed), and how much strength is retained after reaching land – all factors that can render them more dangerous. o In addition, rising sea levels mean that the storm surges that accompany tropical cyclones are even more damaging. • While climate change may mean fewer tropical cyclones overall, those that do form can become more intense and costly. In other words, we are likely to see more of the really strong and destructive tropical cyclones. • A La Niña event brings an elevated tropical cyclone risk for Australia, as there are typically more tropical cyclones in the Australian region than during El Niño years. BACKGROUND Tropical cyclones, known as hurricanes in the North Atlantic and Northeast Pacific, typhoons in the Northwest Pacific, and simply as tropical cyclones in the South Pacific and Indian Oceans, are among the most destructive of extreme weather events. Many Pacific Island Countries, including Fiji, Vanuatu, Solomon Islands and Tonga, lie within the South Pacific cyclone basin. -

Pull up Banner Tropical Cycclone.Ai

Air released Eye air Warm air Cold rises Steady winds Eye Warm air A tropical Cyclone (also known as typhoons or hurricanes) is a violent rotating windstorm that develops over warm tropical waters warner than 26.5°C and located between 5° and 15°latitude. Tropical Cyclones affect nearly all Pacific Islands countries and are the most frequent hazard to affect Fiji with around 2 – 3 cyclones occurring every year. As a result of climate change, cyclone frequency has doubled in the last decade. The cyclone season in Fiji runs from November to April and some cyclones do occur outside the season. T ropical Cyclone Strong winds can devastating western Viti Levu continue for hours, days, and killing seven people. even causing widespread damage to buildings, Storm surges and waves infrastructure and created by low atmospheric vegetation and causing pressure and strong cyclonic loss of life. winds blowing over long distance. A storm surge is a Wind speed levels of a raised dome of seawater about tropical cyclone are; 60-80km wide and 2-5m higher Gale Force Winds : 63-87 km/h than normal sea level. As the Storm force winds : 88-117 km/h cyclone makes landfall, storm Hurricane force winds : 117 + km/h surge and waves inundate coastal areas. At the coast, Torrential rains can result in widespread flash flooding and storm surge and waves are the river flooding. Up to 600mm and more of high intensity rain can greatest threat to life and be produced in one day. These rains can also trigger property and also cause severe landslides in hilly areas, which may already be sodden due to coastal erosion. -

The Impact of Tropical Cyclone Hayan in the Philippines: Contribution of Spatial Planning to Enhance Adaptation in the City of Tacloban

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS Faculdade de Ciências Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas Faculdade de Letras Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia Instituto de Ciências Sociais Instituto Superior de Agronomia Instituto Superior Técnico The impact of tropical cyclone Hayan in the Philippines: Contribution of spatial planning to enhance adaptation in the city of Tacloban Doutoramento em Alterações Climáticas e Políticas de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Especialidade em Ciências do Ambiente Carlos Tito Santos Tese orientada por: Professor Doutor Filipe Duarte Santos Professor Doutor João Ferrão Documento especialmente elaborado para a obtenção do grau de Doutor 2018 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS Faculdade de Ciências Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas Faculdade de Letras Faculdade de Ciências e Tecnologia Instituto de Ciências Sociais Instituto Superior de Agronomia Instituto Superior Técnico The impact of tropical cyclone Haiyan in the Philippines: Contribution of spatial planning to enhance adaptation in the city of Tacloban Doutoramento em Alterações Climáticas e Políticas de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Especialidade em Ciências do Ambiente Carlos Tito Santos Júri: Presidente: Doutor Rui Manuel dos Santos Malhó; Professor Catedrático Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa Vogais: Doutor Carlos Daniel Borges Coelho; Professor Auxiliar Departamento de Engenharia Civil da Universidade de Aveiro Doutor Vítor Manuel Marques Campos; Investigador Auxiliar Laboratório Nacional de Engenharia Civil(LNEC) -

Pacific Study (Focusing on Fiji, Tonga and Vanuatu

1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Hazard exposure 1.1. Pacific island countries (PICs) are vulnerable to a broad range of natural disasters stemming from hydro-meteorological (such as cyclones, droughts, landslide and floods) and geo-physical hazards (volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and tsunamis). In any given year, it is likely that Fiji, Tonga and Vanuatu are either hit by, or recovering from, a major natural disaster. 1.2. The impact of natural disasters is estimated by the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative as equivalent to an annualized loss of 6.6% of GDP in Vanuatu, and 4.3% in Tonga. For Fiji, the average asset losses due to tropical cyclones and floods are estimated at more than 5%. 1.3. In 2014, Tropical Cyclone (TC) Ian caused damage equivalent to 11% to Tonga's GDP. It was followed in 2018 by damage close to 38% of GDP from TC Gita. In 2015, category five TC Pam displaced 25% of Vanuatu's population and provoked damage estimated at 64% of GDP. In Fiji, Tropical Cyclone Winston affected 62% of the population and wrought damage amounting to 31% of GDP, only some three and a half years after the passage of Tropical Cyclone Evan. 1.4. Vanuatu and Tonga rank number one and two in global indices of natural disaster risk. Seismic hazard is an ever-present danger for both, together with secondary risks arising from tsunamis and landslides. Some 240 earthquakes, ranging in magnitude between 3.3 and 7.1 on the Richter Scale, struck Vanuatu and its surrounding region in the first ten months of 2018. -

Israeli Scholarships for Fijians, Praise for Govt, RFMF

FRIDAY FEBRUARY 21, 2020 l 16 PAGES l ISSUE 3 VOL 11 l WWW.FIJI.GOV.FJ Fijijj Focus Israeli scholarships for Fijians, praise for Govt, RFMF Prime Minister Voreqe Bainimarama with President of the State of Israel, Reuven Rivlin at Pullman Resort and Spa in Wailoaloa, Nadi yesterday. Photo: NANISE NEIMILA DEEPER TIES MEREANI GONEDUA nouncement, highlighted that the new Pacific. This collaboration will enable us to culture that has enabled their relationship to scholarships would begin in August this work together to apply Israeli innovation deepen over the years. TOTAL of 100 new scholarships year for students interested in agriculture. to pressing challenges such as food secu- While acknowledging Fiji’s contribution for Fiji and the Pacific island coun- “I am also proud to announce that Israel rity, climate change, ocean rise and public towards peacekeeping, President Rivlin also A tries has been announced by Israel will open a centre of excellence and in- health. President, Reuven Rivlin. novation for Pacific Island States in col- President Rivlin said Fiji and Israel have President Rivlin, while making the an- laboration with the University of the South cooperated in many fields apart from agri- CONTINUES ON PAGE 3 email: [email protected]; @FijianGovt; Fijian Government; visit us @ www.fiji.gov.fj NATIONAL MATTERS phone: 3301806 Work on common goals, minister urges PICs INSIDE AZARIA FAREEN ACIFIC Island Countries (PICs) should work togeth- $17M GRANT FOR Per towards their common DISASTER RESILIENCE - 15 goal despite challenges linked to changing climate, frayed interna- GOVT PRAISED FOR BRINGING tional markets and threats to the POWER TO COMMUNITY - 14 multilateral trading system. -

ADRA Samoa Photo Courtesy of Su’A Julia Wallork

Volunteers for ADRA Samoa Photo courtesy of Su’a Julia Wallork. ADRA Samoa SU’A JULIA WALLWORK Su’a Julia Wallwork is the country director for ADRA Samoa. She is a member of the Executive Committee of the South Pacific Division of the Seventh Day Adventist Church, since 2015. Wallwork grew up in the Seventh Day Adventist Church, but in her adult life, strayed for 35 years. Her parents never stopped praying for her, and she believes God answered their prayers, and that is why she is blessed to be where she is today – in the Master’s Service. The Adventist Development and relief Agency (ADRA) Samoa, located in Apia, the capital of Samoa,1 has its office on the compound of the Seventh Day Adventist Church headquarters for Samoa and Tokelau. Samoa became an Independent nation in 1962, after being governed by Germany, Great Britain, and New Zealand. It is an archipelago consisting of the islands of Savaii, Upolu, Apolima, and Manono. The country director is Su’a Julia Wallwork, who has managed the agency since 2009. Because it is mainly project-funded, its staff will vary according to current projects. During the period 2016-2019 it had 31 staff members while at the beginning of 2020 it had 14 ADRA staff. Although the Adventist Church had engaged with local communities through various outreach programs, ADRA only began activities in Samoa after the cyclones Ofa in 1990 and Val in 1991. After ADRA provided clothing, rope, tarpaulins, and AUD$10,000 worth of food and emergency supplies, it began to become known by the public. -

Cyclone Winston Fiji

UNICEF PACIFIC CYCLONE WINSTON SITUATION REPORT Reporting Period 3-4 March 2016 Cyclone Winston Fiji Humanitarian Situation Report #6 ©UNICEF/2016/Sokhin Photo: Water tanks are a vital source of rural life in Fiji. This is just one of many destroyed by As of 4 March 2016 Cyclone Winston. UNICEF prioritises provision of clean safe drinking water and sanitation supplies to prevent the spread of disease. 120,000 Estimated # of children likely to have been Highlights moderately to severely affected (40% of child population) Category 5 Cyclone Winston, the strongest cyclone to ever hit Fiji and with some of the highest wind speeds at landfall ever recorded globally, severely affected around 40% of the population. 350,000 Estimated # of people likely to have been US$ 38.6 million Flash Appeal has been launched, including moderately to severely affected (40% of US$ 7.1 million for UNICEF projects. total population) An estimated 29,000+ people are living in 722 evacuation centres, Up to 250,000 people in need of including in 71 schools (Evacuation centres in Central Division WASH assistance due to electricity, closed). water and sewerage service disruptions UNICEF supplies have provided safe drinking water for over 26,000 people and are assisting 6,000 students to return to school. UNICEF Appeal within A ship with school and WASH supplies from UNICEF Vanuatu has UN Flash Appeal arrived in Suva Harbour; supplies from UNICEF Solomon Islands US$ 7.1 million being packed for shipping to Fiji; Emergency Charter Flight with health and school supplies arriving on 7 March. UNICEF’s response with partners US$ 369,849 of UNICEF supplies pre-positioned in Fiji have been provided to the Government of Fiji and are being distributed to the most affected people. -

Fiji Climate Summary December 2019

FIJI METEOROLOGICAL SERVICE ISO 9001:2015 Private Mail Bag (NAP0351) Fiji Climate Summary certified Climate Nadi Airport, Fiji Services Ph: +679 6724888 Fax: +679 6724050 Email: [email protected] December 2019 Also online at: http://www.met.gov.fj Issued: January 9, 2020 Since : August 1980* Volume 40 : Issue 12 1. IN BRIEF The El Niño Southern Oscillation continued to be in a neu- with 275mm and Natawa with 250mm, all on the same day. tral state during December 2019. The main weather feature Furthermore, Vunisea registered a record breaking Decem- for the month was tropical cyclone Sarai. ber’s daily rainfall for the station since observation began in 1929 with 212mm on the 27th. Tropical depression, TD03F, the predecessor of tropical cyclone Sarai, affected the Fiji group with heavy rainfall on Sarai also resulted in very high intensity rainfall with Qawa th the 26 , especially in the Northern Division. Saqani re- and Vaturekuka in Labasa registering hourly rainfall of ceived 144mm of rainfall, followed by Vaturekuka with 76mm and 65mm, respectively, at 10am (Fiji Standard th 117mm and Udu Point with 116mm, all on the 26 . Time - FST) on the 28th, followed by Monasavu with 64mm at 6pm (FST) on the 27th and Nadarivatu with 56mm at After attaining tropical cyclone intensity on the 27th, Sarai 7pm (FST) on the 27th. Consequently, several places were passed to the west of the Fiji Group, before making an east- flooded. erly turn on the south of Kadavu in the early hours of the 28th, passing through the Lau Group in a southeasterly di- Apart from the rainfall brought by Sarai in the last week of rection and exiting the Fiji Waters by 30th. -

Shelter and Settlements Risk Profile NATURAL DISASTERS from 1980

Shelter and Settlements Risk Profile ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter HISTORIC EVENTS (ReliefWeb) Dec 2012 1. Tropical Cyclone Evan KEY DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS Tropical Cyclone Evan (TC Evan) − a Category 4 cyclone, wind Full Name: Republic Of The Fiji Islands speeds of 210 km/h (130 mph), impacted Northern Vanua Population: 862,333 (UN, 2012) Levu and Western Viti Levu on 17 December 2012,is Annual Growth Rate: 0.5% considered one of the worst to ever hit Fiji in recent history. Capital: Suva Approximately 60% of the total population were affected in Population In Urban Areas: 52.90% the post-disaster period. The Northern division recorded the Area: 18,376 Sq Km(7,095 Sq.mile) highest percentage of affected population (52%) as a Major Languages: English, Fijian, Hindi proportion of their total population, followed by the Western Division (38%) and the Central and Eastern divisions (23%). Major Religions: Christianity, Hinduism, Islam March 2. Fiji: Floods Life Expectancy: (UN) 67 Years (M)/72 Years (W) 2012 Monetary Unit: 1 Fijian Dollar = 100 Cents Severe flooding in the areas of Ra, Tavua, Ba, Lautoka, Nadi, Main Exports: Sugar, Clothing, Gold, Processed Nadroga, Sigatoka, and Rewa in January 2012 The Fish, Timber Government of Fiji estimated that damage from the 2012 GNI Per Capita: US $3,720 (WB) 5,390 (FS) floods was at approximately F$71 million. This suggests that Human Development Index: 0.6881 Fiji experienced damage of F$146 million in 2012 alone. Rainfall In Capital (Mm): 3040 Jan 3. Fiji: Floods Temperature In Capital City ° C: 22.2/28.7 2012 Average Family Size: 5 March 4. -

J-PRISM Progress Report

Japanese Technical Cooperation Project for Promotion of Regional Initiative on Solid Waste Management in Pacific Island Countries J‐PRISM Progress Report May 2013 1 Japanese Technical Cooperation Project for Promotion of Regional Initiative on Solid Waste Management in Pacific Island Countries Table of Contents Regional Activities Update ........................................................................................................................ 3 Federated States of Micronesia* .............................................................................................................. 6 Fiji* ........................................................................................................................................................... 10 Kiribati* ................................................................................................................................................... 21 Marshall Islands* .................................................................................................................................... 25 Palau* ...................................................................................................................................................... 28 Papua New Guinea* ................................................................................................................................ 31 Samoa* .................................................................................................................................................... 34 Solomon -

The Cost of Disaster on Your Business

eepim o K pe KOST BLO DISASTA LO n bIsnIs BISNIS BLO IU P I PS O. ORG PEN Iu save tu ril kost blo disasta lo bisnis blo iu? Hemia nao .FJ/STAYO samfala tru samting wea evri bisnis onas lo Pasifik sud save. 80% lo kampanis wea no rikava from disasta insaed wan manis, bae go aot lo bisnis.2 IU SAVE TU DAT... Diswan hem estimeit kost blo SAEKLON WINSTON FIJI 2016 dameij an los blo praevet sekta lo Fiji taem Saeklon Winston 1 aot lo evri 4 bisnisis no 3 FJ 1.5 BILLION kasem olketa lo 2016. save savaev afta evri biki 1 disasta happen. (US$ 722,698,500) Onli wanfa we fo meksua Totol pesenol inkam los blo staf an emploiis afta Saeklon bisnis blo iu hem savaev from INKAM LOS FROM SAEKLON WINSTON Winston lo 2016, bikos olketa no disasta o advesiti: go waka insaed 14,450,129 deis. FJ 351.45 MILLION Diswan no onli soum impakt wea disasta garem lo wok prodaktiviti fo bisnis bat bikos olketa no (US$ 169,328,258) go baek lo waka kwuik taem fo komiuniti blo olketa.4 Totol ikonomik valiu blo ifekts wea Tropikol Saeklon Pam kosim SAEKLON PAM. VANUATU.2015 lo Vanuatu lo 2015.5 VT 48.6 BILLION Krietim wanfala bisnis plan an mekem hem waka. (US$ 449.4 MILLION) Sapos iu no garem BCP iet o no save gud abaotim, daon loudim BCP templet an krieitim wanfala fo iu seleva, iusim na Negativ grouth rate lo Vanuatu tuelfala step gaed wea save tekem iu tuelf Daonten Lo afta Tropikol Saeklon Pam hem minit nomoa fo komplitim insaed. -

Global Climate Risk Index 2018

THINK TANK & RESEARCH BRIEFING PAPER GLOBAL CLIMATE RISK INDEX 2018 Who Suffers Most From Extreme Weather Events? Weather-related Loss Events in 2016 and 1997 to 2016 David Eckstein, Vera Künzel and Laura Schäfer Global Climate Risk Index 2018 GERMANWATCH Brief Summary The Global Climate Risk Index 2018 analyses to what extent countries have been affected by the impacts of weather-related loss events (storms, floods, heat waves etc.). The most recent data available – for 2016 and from 1997 to 2016 – were taken into account. The countries affected most in 2016 were Haiti, Zimbabwe as well as Fiji. For the period from 1997 to 2016 Honduras, Haiti and Myanmar rank highest. This year’s 13th edition of the analysis reconfirms earlier results of the Climate Risk Index: less developed countries are generally more affected than industrialised countries. Regarding future climate change, the Climate Risk Index may serve as a red flag for already existing vulnerability that may further increase in regions where extreme events will become more frequent or more severe due to climate change. While some vulnerable developing countries are frequently hit by extreme events, for others such disasters are a rare occurrence. It remains to be seen how much progress the Fijian climate summit in Bonn will make to address these challenges: The COP23 aims to continue the development of the ‘rule-book’ needed for implementing the Paris Agreement, including the global adaptation goal and adaptation communication guidelines. A new 5-year-work plan of the Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage is to be adopted by the COP.