Ancient Board Games Duodecim Scripta & Tabula

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Game Board Rota

GAME BOARD ROTA This board is based on one found in Roman Libya. INFORMATION AND RULES ROTA ABOUT WHAT YOU NEED “Rota” is a common modern name for an easy strategy game played • 2 players on a round board. The Latin name is probably Terni Lapilli (“Three • 1 round game board like a wheel with 8 spokes (download and print pebbles”). Many boards survive, both round and rectangular, and ours, or draw your own) there must have been variations in play. • 1 die for determining who starts first • 3 playing pieces for each player, such as light and dark pebbles or This is a very simple game, and Rota is especially appropriate to play coins (heads and tails). You can also cut out our gaming pieces and with young family members and friends! Unlike Tic Tac Toe, Rota glue them to pennies or circles of cardboard avoids a tie. RULES Goal: The first player to place three game pieces in a row across the center or in the circle of the board wins • Roll a die or flip a coin to determine who starts. The higher number plays first • Players take turns placing one piece on the board in any open spot • After all the pieces are on the board, a player moves one piece each turn onto the next empty spot (along spokes or circle) A player may not • Skip a turn, even if the move forces you to lose the game • Jump over another piece • Move more than one space • Land on a space with a piece already on it • Knock a piece off a space Changing the rules Roman Rota game carved into the forum pavement, Leptis Magna, Libya. -

Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them, Being the Games Of

CO CD CO GAMES ANCIENT AND ORIENTAL AND HOW TO PLAY THEM. BEING THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS THE HIERA GRAMME OF THE GREEKS, THE LUDUS LATKUNCULOKUM OF THE ROMANS AND THE ORIENTAL GAMES OF CHESS, DRAUGHTS, BACKGAMMON AND MAGIC SQUAEES. EDWARD FALKENER. LONDON: LONGMANS, GEEEN AND Co. AND NEW YORK: 15, EAST 16"' STREET. 1892. All rights referred. CONTENTS. I. INTRODUCTION. PAGE, II. THE GAMES OF THE ANCIENT EGYPTIANS. 9 Dr. Birch's Researches on the games of Ancient Egypt III. Queen Hatasu's Draught-board and men, now in the British Museum 22 IV. The of or the of afterwards game Tau, game Robbers ; played and called by the same name, Ludus Latrunculorum, by the Romans - - 37 V. The of Senat still the modern and game ; played by Egyptians, called by them Seega 63 VI. The of Han The of the Bowl 83 game ; game VII. The of the Sacred the Hiera of the Greeks 91 game Way ; Gramme VIII. Tlie game of Atep; still played by Italians, and by them called Mora - 103 CHESS. IX. Chess Notation A new system of - - 116 X. Chaturanga. Indian Chess - 119 Alberuni's description of - 139 XI. Chinese Chess - - - 143 XII. Japanese Chess - - 155 XIII. Burmese Chess - - 177 XIV. Siamese Chess - 191 XV. Turkish Chess - 196 XVI. Tamerlane's Chess - - 197 XVII. Game of the Maharajah and the Sepoys - - 217 XVIII. Double Chess - 225 XIX. Chess Problems - - 229 DRAUGHTS. XX. Draughts .... 235 XX [. Polish Draughts - 236 XXI f. Turkish Draughts ..... 037 XXIII. }\'ci-K'i and Go . The Chinese and Japanese game of Enclosing 239 v. -

The Game of Ur: an Exercise in Strategic Thinking and Problem Solving and a Fun Math Club Activity

Pittsburg State University Pittsburg State University Digital Commons Open Educational Resources - Math Open Educational Resources 2019 The Game of Ur: An Exercise in Strategic Thinking and Problem Solving and A Fun Math Club Activity Cynthia J. Huffman Ph.D. Pittsburg State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/oer-math Part of the Other Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Huffman, Cynthia J. Ph.D., "The Game of Ur: An Exercise in Strategic Thinking and Problem Solving and A Fun Math Club Activity" (2019). Open Educational Resources - Math. 15. https://digitalcommons.pittstate.edu/oer-math/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Educational Resources at Pittsburg State University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Educational Resources - Math by an authorized administrator of Pittsburg State University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Game of Ur An Exercise in Strategic Thinking and Problem Solving and A Fun Math Club Activity by Dr. Cynthia Huffman University Professor of Mathematics Pittsburg State University The Royal Game of Ur, the oldest known board game, was first excavated from the Royal Cemetery of Ur by Sir Leonard Woolley around 1926. The ancient Sumerian city-state of Ur, located in the lower right corner of the map of ancient Mesopotamia below, was a major urban center on the Euphrates River in what is now southern Iraq. Mesopotamia in 2nd millennium BC https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mesopotamia_in_2nd_millennium_BC.svg Joeyhewitt [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)] Dr. -

100 Games from Around the World

PLAY WITH US 100 Games from Around the World Oriol Ripoll PLAY WITH US PLAY WITH US 100 Games from Around the World Oriol Ripoll Play with Us is a selection of 100 games from all over the world. You will find games to play indoors or outdoors, to play on your own or to enjoy with a group. This book is the result of rigorous and detailed research done by the author over many years in the games’ countries of origin. You might be surprised to discover where that game you like so much comes from or that at the other end of the world children play a game very similar to one you play with your friends. You will also have a chance to discover games that are unknown in your country but that you can have fun learning to play. Contents laying traditional games gives people a way to gather, to communicate, and to express their Introduction . .5 Kubb . .68 Pideas about themselves and their culture. A Game Box . .6 Games Played with Teams . .70 Who Starts? . .10 Hand Games . .76 All the games listed here are identified by their Guess with Your Senses! . .14 Tops . .80 countries of origin and are grouped according to The Alquerque and its Ball Games . .82 similarities (game type, game pieces, game objective, Variations . .16 In a Row . .84 etc.). Regardless of where they are played, games Backgammon . .18 Over the Line . .86 express the needs of people everywhere to move, Games of Solitaire . .22 Cards, Matchboxes, and think, and live together. -

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan

The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia : Tajikistan 著者 Ubaidulloev Zubaidullo journal or The bulletin of Faculty of Health and Sport publication title Sciences volume 38 page range 43-58 year 2015-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2241/00126173 筑波大学体育系紀要 Bull. Facul. Health & Sci., Univ. of Tsukuba 38 43-58, 2015 43 The History and Characteristics of Traditional Sports in Central Asia: Tajikistan Zubaidullo UBAIDULLOEV * Abstract Tajik people have a rich and old traditions of sports. The traditional sports and games of Tajik people, which from ancient times survived till our modern times, are: archery, jogging, jumping, wrestling, horse race, chavgon (equestrian polo), buzkashi, chess, nard (backgammon), etc. The article begins with an introduction observing the Tajik people, their history, origin and hardships to keep their culture, due to several foreign invasions. The article consists of sections Running, Jumping, Lance Throwing, Archery, Wrestling, Buzkashi, Chavgon, Chess, Nard (Backgammon) and Conclusion. In each section, the author tries to analyze the origin, history and characteristics of each game refering to ancient and old Persian literature. Traditional sports of Tajik people contribute as the symbol and identity of Persian culture at one hand, and at another, as the combination and synthesis of the Persian and Central Asian cultures. Central Asia has a rich history of the traditional sports and games, and significantly contributed to the sports world as the birthplace of many modern sports and games, such as polo, wrestling, chess etc. Unfortunately, this theme has not been yet studied academically and internationally in modern times. Few sources and materials are available in Russian, English and Central Asian languages, including Tajiki. -

Enumerating Backgammon Positions: the Perfect Hash

Enumerating Backgammon Positions: The Perfect Hash By Arthur Benjamin and Andrew M. Ross ABSTRACT Like many games, people place money wagers on backgammon games. These wagers can change during the game. In order to make intelligent bets, one needs to know the chances of winning at any point in the game. We were working on this for positions near the end of the game when we needed to explicitly label each of the positions so the computer could refer to them. The labeling developed here uses the least possible amount of computer memory, is reasonably fast, and works well with a technique known as dynamic programming. INTRODUCTION The Game of Backgammon Backgammon is played on a board with 15 checkers per player, and 24 points (orga nized into four tables of six points each) that checkers may rest on. Players take turns rolling the two dice to move checkers toward their respective "home boards," and ulti mately off the board. The first player to move all of his checkers off the board wins. We were concerned with the very end of the game, when each of the 15 checkers is either on one of the six points in the home board, or off the board. This is known as the "bearoff," since checkers are borne off the board at each turn. Some sample bearoff posi tions are shown in Figure 1. We wanted to calculate the chances of winning for any arrangement of positions in the bearoff. To do this, we needed to have a computer play backgammon against itself, to keep track of which side won more often. -

Temporal Difference Learning Algorithms Have Been Used Successfully to Train Neural Networks to Play Backgammon at Human Expert Level

USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F. MATTHEWS (Under the direction of Khaled Rasheed) ABSTRACT Temporal difference learning algorithms have been used successfully to train neural networks to play backgammon at human expert level. This approach has subsequently been applied to deter- ministic games such as chess and Go with little success, but few have attempted to apply it to other nondeterministic games. We use temporal difference learning to train neural networks for four such games: backgammon, hypergammon, pachisi, and Parcheesi. We investigate the influ- ence of two training variables on these networks: the source of training data (learner-versus-self or learner-versus-other game play) and its structure (a simple encoding of the board layout, a set of derived board features, or a combination of both of these). We show that this approach is viable for all four games, that self-play can provide effective training data, and that the combination of raw and derived features allows for the development of stronger players. INDEX WORDS: Temporal difference learning, Board games, Neural networks, Machine learning, Backgammon, Parcheesi, Pachisi, Hypergammon, Hyper-backgammon, Learning environments, Board representations, Truncated unary encoding, Derived features, Smart features USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F. MATTHEWS B.S., Georgia Institute of Technology, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF SCIENCE ATHENS,GEORGIA 2006 © 2006 Glenn F. Matthews All Rights Reserved USING TEMPORAL DIFFERENCE LEARNING TO TRAIN PLAYERS OF NONDETERMINISTIC BOARD GAMES by GLENN F. -

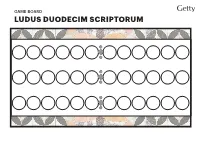

Ludus Duodecim Scriptorum Game Board Ludus Duodecim Scriptorum

GAME BOARD LUDUS DUODECIM SCRIPTORUM GAME BOARD LUDUS DUODECIM SCRIPTORUM L E V A T E D I A L O U L U D E R E N E S C I S I D I O T A R E C E D E This inscribed board says: “Get up, get lost. You don’t know how to play! Idiot, give up!” Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL) xiv.4125 INFORMATION AND RULES LUDUS DUODECIM SCRIPTORUM ABOUT Scholars have reconstructed the direction of play based on a beginner’s board with a sequence of letters. Roland Austin and This game of chance and strategy is a bit like Backgammon, and it Harold Murray figured out the likely game basics in the early takes practice. The game may last a long time—over an hour. Start to twentieth century. Rules are adapted from Tabula, a similar game play a first round to learn the rules before getting more serious—or before deciding to tinker with the rules to make them easier! WHAT YOU NEED We provide two boards to choose from, one very plain, and another • 2 players with six-letter words substituted for groups of six landing spaces. • A game board with 3 rows of 12 game spaces (download and print Romans loved to gamble, and some scholars conjecture that ours, or draw your own) Duodecim boards with writing on them were intended to disguise their • 5 flat identifiably different game pieces for each player. They will be function at times when authorities were cracking down on betting. stacked. Pennies work: heads for one player, tails for the other Some boards extolled self-care, Roman style; one says: “To hunt, to • You can also print and cut out our gaming pieces and glue them to bathe, to play, to laugh, this is to live!” Another is a tavern’s menu: pennies or cardboard “We have for dinner: chicken, fish, ham, peacock.” But some boards • 3 six-sided dice are too obvious to fool anyone. -

Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-1992 Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance Leon Stratikis University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Stratikis, Leon, "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1992. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Leon Stratikis entitled "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Paul Barrette, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: James E. Shelton, Patrick Brady, Bryant Creel, Thomas Heffernan Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation by Leon Stratikis entitled Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. -

Games & Puzzles Magazine (Series 1 1972

1 GAMES & PUZZLES MAGAZINE (SERIES 1 1972-1981) INDEX Preliminary Notes [DIP] Diplomacy - Don Turnbull 1-10 [DIP] Diplomacy - Alan Calhamer 37-48 G&P included many series, and where a game [DRA] Draughts - 'Will o' the Wisp' 19-30 reference relates to a series, a code in square brackets [FAN] Fantasy Games - 'Warlock' 79-81 is added. [FIG] Figures (Mathematics) - Many authors 19-71 The table below lists the series in alphabetical order [FO] Forum (Reader's letters) 1-81 [GV] Gamesview (Game reviews) 6-81 with the code shown in the left hand column. [GGW] Great Games of the World - David Patrick 6-12 Principal authors are listed together with the first and [GO] Go - Francis Roads 1-12 last issue numbers. Small breaks in publication of a [GO] Go - John Tilley 13-24 series are not noted. Not all codes are required in the [GO] Go - Stuart Dowsey 31-43 body of the index. [GO] Go, annotated game - Francis Roads 69-74 Book reviews were initially included under [MAN] Mancala - Ian Lenox-Smith 26-29 Gamesview, but under Bookview later. To distinguish [MW] Miniature Warfare - John Tunstill 1-6 book reviews from game reviews all are coded as [BV]. [OTC] On the Cards - David Parlett 29-73 [PG] Parade Ground (Wargames) - Nicky Palmer 51-81 References to the Forum series (Reader's letters - [PB] Pieces and Bits - Gyles Brandreth 1-19 Code [FO]) are restricted to letters judged to [PEN] Pentominoes - David Parlett 9-17 contribute relevant information. [PLA] Platform - Authors named in Index 64-71 Where index entries refer consecutively to a particular [PR] Playroom 43-81 game the code is given just once at the end of the [POK] Poker - Henry Fleming 6-12 issue numbers which are not separated by spaces. -

The Primary Education Journal of the Historical Association

Issue 87 / Spring 2021 The primary education journal of the Historical Association The revised EYFS Framework – exploring ‘Past and Present’ How did a volcano affect life in the Bronze Age? Exploring the spices of the east: how curry got to our table Ancient Sumer: the cradle of civilisation ‘I have got to stop Mrs Jackson’s family arguing’: developing a big picture of the Romans, Anglo-Saxons and Vikings Subject leader’s site: assessment and feedback Fifty years ago we lost the need to know our twelve times tables Take one day: undertaking an in-depth local enquiry Belmont’s evacuee children: a local history project Ofsted and primary history One of my favourite history places – Eyam CENTRE SPREAD DOUBLE SIDED PULL-OUT POSTER ‘Twelve pennies make a shilling; twenty shillings make a pound’ Could you manage old money? Examples of picture books New: webinar recording offer for corporate members Corporate membership offers a comprehensive package of support. It delivers all the benefits of individual membership plus an enhanced tier of resources, CPD access and accreditation in order to boost the development of your teaching staff and delivery of your whole-school history provision*. We’re pleased to introduce a NEW benefit for corporate members – the ability to register for a free webinar recording of your choice each academic year, representing a saving of up to £50. Visit www.history.org.uk/go/corpwebinar21 for details The latest offer for corporate members is just one of a host of exclusive benefits for school members including: P A bank of resources for you and up to 11 other teaching staff. -

1 SASANIKA Late Antique Near East Project -.:: GEOCITIES.Ws

SASANIKA Late Antique Near East Project SASANIKA PROJECT: by Touraj Daryaee, California State University, Fullerton ADVISORY BOARD Kamyar Abdi, Dartmouth College Michael Alram, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften Daryoosh Akbarzadeh, National Museum of Iran Parissa Andami, Money Museum, Tehran Bahram Badiyi, Brooks College Carlo G. Cereti, University of Rome Erich Kettenhofen, University of Trier Richard N. Frye, Harvard University Mohammad Reza Kargar, National Museum of Iran Judith Lerner, Independent Scholar Maria Macuch, Free University of Berlin Michael G. Morony, University of California, Los Angeles Antonio Panaino, University of Bologna James Russell, Harvard University A. Shapur Shahbazi, Eastern Oregon University Rahim Shayegan, Harvard University P. Oktor Skjærvø, Harvard University Evangelos Venetis, University of Edinburgh Joel T. Walker, University of Washington Donald Whitcomb, University of Chicago ADVISORY COMMITTEE Ali Makki Jamshid Varza WEBSITE COORDINATORS Haleh Emrani Khodadad Rezakhani 1 One of the most remarkable empires of the first millennium CE was that of the Sasanian Persian Empire. Emanating from southern Iran’s Persis region in the third century AD, the Sasanian domain eventually encompassed not only modern day Iran and Iraq, but also the greater part of Central Asia and the Near East, including at times, the regions corresponding to present-day Israel, Turkey, and Egypt. This geographically diverse empire brought together a striking array ethnicities and religious practices. Arameans, Arabs, Armenians, Persians, Romans, Goths as well as a host of other peoples all lived and labored under Sasanian rule. The Sasanians in fact established a relatively tolerant imperial system, creating a vibrant communal life among its Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian citizens. This arrangement which allowed religious officials to take charge of their own communities was a model for the Ottoman millet system.