Arxiv:2102.07912V3 [Cond-Mat.Str-El] 18 Jul 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dirac Cones in Two-Dimensional Borane

Edinburgh Research Explorer Dirac cones in two-dimensional borane Citation for published version: Martinez-Canales, M, Galeev, TR, Boldyrev, AI & Pickard, CJ 2017, 'Dirac cones in two-dimensional borane', Physical Review B, vol. 96, no. 19, pp. 195442. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevB.96.195442 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1103/PhysRevB.96.195442 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Physical Review B Publisher Rights Statement: (C) 2017 American Physical Society General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 PHYSICAL REVIEW B 96, 195442 (2017) Dirac cones in two-dimensional borane Miguel Martinez-Canales,1,2,* Timur R. Galeev,3 Alexander I. Boldyrev,3 and Chris J. Pickard2,4,5,† 1SUPA, School of Physics and Astronomy & EPCC, University of Edinburgh, Peter Guthrie Tait Road, Edinburgh EH9 3FD, -

Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018

The 100% Unofficial Quick Guide to the Eurovision Song Contest 2018 O Guia Rápido 100% Não-Oficial do Eurovision Song Contest 2018 for Commentators Broadcasters Media & Fans Compiled by Lisa-Jayne Lewis & Samantha Ross Compilado por Lisa-Jayne Lewis e Samantha Ross with Eleanor Chalkley & Rachel Humphrey 2018 Host City: Lisbon Since the Neolithic period, people have been making their homes where the Tagus meets the Atlantic. The sheltered harbour conditions have made Lisbon a major port for two millennia, and as a result of the maritime exploits of the Age of Discoveries Lisbon became the centre of an imperial Portugal. Modern Lisbon is a diverse, exciting, creative city where the ancient and modern mix, and adventure hides around every corner. 2018 Venue: The Altice Arena Sitting like a beautiful UFO on the banks of the River Tagus, the Altice Arena has hosted events as diverse as technology forum Web Summit, the 2002 World Fencing Championships and Kylie Minogue’s Portuguese debut concert. With a maximum capacity of 20000 people and an innovative wooden internal structure intended to invoke the form of Portuguese carrack, the arena was constructed specially for Expo ‘98 and very well served by the Lisbon public transport system. 2018 Hosts: Sílvia Alberto, Filomena Cautela, Catarina Furtado, Daniela Ruah Sílvia Alberto is a graduate of both Lisbon Film and Theatre School and RTP’s Clube Disney. She has hosted Portugal’s edition of Dancing With The Stars and since 2008 has been the face of Festival da Cançao. Filomena Cautela is the funniest person on Portuguese TV. -

Convocation Spring 2020

DALHOUSIE UNIVERSITY CONVOCATION SPRING 2020 Table of Contents ______________________________________________________________ Messages to Graduates 1 Faculties of Dentistry and Graduate Studies 23 Convocation and Ceremonial Elements 3 Diploma in Dental Hygiene 23 Bachelor of Dental Hygiene 23 Faculties of Agriculture and Graduate Studies 5 Doctor of Dental Surgery 23 Diploma in Engineering 5 Master of Periodontics 24 Diploma in Technology 5 Master of Science 24 Bachelor of Agriculture 6 Bachelor of Science (Agriculture) 6 Faculties of Engineering and Graduate Studies 25 Bachelor of Science (Bioveterinary Science) 7 Diploma in Engineering 25 Bachelor of Technology 7 Bachelor of Engineering 26 Master of Science 8 Master of Applied Science 35 Master of Engineering 36 Faculties of Architecture & Planning and Graduate Doctor of Philosophy 37 Studies 9 Bachelor of Community Design 9 Faculties of Health and Graduate Studies 39 Bachelor of Environmental Design Studies 9 Diploma in Emergency Health Services Master of Architecture 10 Management 39 Master of Planning 10 Diploma in Health Services Administration 39 Bachelor of Health Science 39 Faculties of Arts & Social Sciences and Graduate Bachelor of Science (Health Promotion) 39 Studies 11 Bachelor of Science (Kinesiology) 40 Bachelor of Arts (King’s) 11 Bachelor of Science (Nursing) 41 Bachelor of Music (King’s) 12 Bachelor of Science (Pharmacy) 41 Diploma in Costume Studies 12 Bachelor of Science (Recreation) 42 Bachelor of Arts 12 Bachelor of Social Work 43 Bachelor of Music 16 Master of Arts -

REFLECTIONS 148X210 UNTOPABLE.Indd 1 20.03.15 10:21 54 Refl Ections 54 Refl Ections 55 Refl Ections 55 Refl Ections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS MERCI CHÉRIE – MERCI, JURY! AUSGABE 2015 | ➝ Es war der 5. März 1966 beim Grand und belgischen Hitparade und Platz 14 in Prix d’Eurovision in Luxemburg als schier den Niederlanden. Im Juni 1966 erreichte Unglaubliches geschah: Die vielbeachte- das Lied – diesmal in Englisch von Vince te dritte Teilnahme von Udo Jürgens – Hill interpretiert – Platz 36 der britischen nachdem er 1964 mit „Warum nur war- Single-Charts. um?“ den sechsten Platz und 1965 mit Im Laufe der Jahre folgten unzähli- SONG CONTEST CLUBS SONG CONTEST 2015 „Sag‘ ihr, ich lass sie grüßen“ den vierten ge Coverversionen in verschiedensten Platz belegte – bescherte Österreich end- Sprachen und als Instrumentalfassungen. Wien gibt sich die Ehre lich den langersehnten Sieg. In einem Hier bestechen – allen voran die aktuelle Teilnehmerfeld von 18 Ländern startete Interpretation der grandiosen Helene Fi- der Kärntner mit Nummer 9 und konnte scher – die Versionen von Adoro, Gunnar ÖSTERREICHISCHEN schließlich 31 Jurypunkte auf sich verei- Wiklund, Ricky King und vom Orchester AUSSERDEM nen. Ein klarer Sieg vor Schweden und Paul Mauriat. Teilnehmer des Song Contest 2015 – Rückblick Grand Prix 1967 in Wien Norwegen, die sich am Podest wiederfan- Hier sieht man das aus Brasilien stam- – Vorentscheidung in Österreich – Das Jahr der Wurst – Österreich und den. mende Plattencover von „Merci Cherie“, DAS MAGAZIN DES der ESC – u.v.m. Die Single erreichte Platz 2 der heimi- das zu den absoluten Raritäten jeder Plat- schen Single-Charts, Platz 2 der deutschen tensammlung zählt. DIE LETZTE SEITE ections | Refl AUSGABE 2015 2 Refl ections 2 Refl ections 3 Refl ections 3 Refl ections INHALT VORWORT PRÄSIDENT 4 DAS JAHR DER WURST 18 GRAND PRIX D'EUROVISION 60 HERZLICH WILLKOMMEN 80 „Building bridges“ – Ein Lied Pop, Politik, Paris. -

Industrial Application of a Partitioning Scheduler to Support Mixed Criticality Systems

This is a repository copy of Industrial Application of a Partitioning Scheduler to Support Mixed Criticality Systems. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/148617/ Version: Published Version Proceedings Paper: Law, Stephen Andrew, Bate, Iain John orcid.org/0000-0003-2415-8219 and Lesage, Benjamin Michael Jean-Rene (2019) Industrial Application of a Partitioning Scheduler to Support Mixed Criticality Systems. In: Proceedings of the 31st Euromicro Conference on Real-Time Systems (ECRTS 2019). Reuse This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) licence. This licence allows you to distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as you credit the authors for the original work. More information and the full terms of the licence here: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Industrial Application of a Partitioning Scheduler to Support Mixed Criticality Systems Stephen Law Rolls Royce Control Systems, Birmingham, UK [email protected] Iain Bate The University of York, York, UK [email protected] Benjamin Lesage Rolls Royce Control Systems, Birmingham, UK The University of York, York, UK [email protected] Abstract The ever-growing complexity of safety-critical control systems continues to require evolution in control system design, architecture and implementation. -

A Phenomenology of New Particle Formation (NPF) at Thirteen European Sites

1 2 A Phenomenology of New Particle Formation (NPF) at 3 Thirteen European Sites 4 5 Dimitrios Bousiotis1, Francis D. Pope1, David C. Beddows1, 6 Manuel Dall’Osto2, Andreas Massling3, Jacob Klenø Nøjgaard3,4, 7 Claus Nordstrøm 3, Jarkko V. Niemi5, Harri Portin5, Tuukka Petäjä6, 8 Noemi Perez7, Andrés Alastuey7, Xavier Querol7, Giorgos Kouvarakis8, 9 Stergios Vratolis9, Konstantinos Eleftheriadis9, Alfred Wiedensohler10, 10 10 10 1† 10 Kay Weinhold , Maik Merkel , Thomas Tuch and Roy M. Harrison 11 12 1Division of Environmental Health and Risk Management 13 School of Geography, Earth and Environmental Sciences 14 University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, United Kingdom 15 16 2Institute of Marine Sciences 17 Passeig Marítim de la Barceloneta, 37-49, E-08003, Barcelona, Spain 18 19 3Department of Environmental Science, Aarhus University, 4000 Roskilde, Denmark 20 21 4The National Research Centre for the Working Environment, 2100 Copenhagen, Denmark 22 23 5Helsinki Region Environmental Services Authority (HSY), 24 FI-00066 HSY, Helsinki, Finland 25 26 6Institute for Atmospheric and Earth System Research (INAR) / Physics, Faculty of Science, 27 University of Helsinki, Finland 28 29 7Institute of Environmental Assessment and Water Research (IDAEA - CSIC), 08034, 30 Barcelona, Spain 31 32 8Environmental Chemical Processes Laboratory (ECPL), Department of Chemistry, 33 University of Crete, 70013, Heraklion, Greece To whom correspondence should be addressed (Email: [email protected]) †Also at: Department of Environmental Sciences / Center of Excellence in Environmental Studies, King Abdulaziz University, PO Box 80203, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia 1 34 35 9Environmental Radioactivity Laboratory, Institute of Nuclear and Radiological Science & 36 Technology, Energy & Safety, NCSR Demokritos, Athens, Greece 37 38 10Leibniz Institute for Tropospheric Research (TROPOS), 39 Permoserstr. -

Royal Pedigree-Cenel Nduach and the Mactavish

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Male Lineage and Royal Pedigree Table of the Pictish Cenél nDuach being the Genealogy of the Clan MacTavish Chiefs (From Ancient Times until the 21st century) Copyright by Patrick L. Thompson Extracted from: History of Clan MacTavish , Copyright 2012, Patrick L. Thompson, U.S. Library of Congress Control Number 2012942086 ******************************************************************************************** This Copyrighted Material may not appear on the Internet, except on the Clan MacTavish website at www.clanmactavish.org , and may not be copied or stored by any means whatsoever without the approval of the author/copyright holder. Due to the Ancient Pictish lineage of the MacTavishes, they are not connected nor are they related to the later Teutonic Thomsons of the Scottish Lowlands and Borders. 1. Conall Gulban – King of Tir Connaill (Tyr Connall or Tir Chonall), of whom the Cenél Conaill descended from Conn of the Hundred Battles (not Niall of the Nine Hostages or the dynastic Ui Neills who later conquered much of the north of Ireland). The ancestry of these northern tribes and their kings is proclaimed in the Chronicon Scotorum as belonging to the Sil Cuinn (Race of Conn), not Ui Neill. The Ui Neill link appears as a synthetic fabrication of the dynastic Ui Neill historians of the 13 th century, who rewrote parts of the Irish annals to their advantage. The Chronicon Scotorum , it seems had been overlooked and to have retained its original nature. Conal Gulban’s kindred, the Cenél Conaill, and its branches are Picts (Irish Cruithne), and not Celtic/Gaels related to Niall of the Nine Hostages (although some consider the Picts a Celtic people). -

Instructors in Soledad School Describe It As 'Like Any Other

June Graduates La Torre on Sale graduating In dose Seniors Ls Torre, San Jose State year- pick up commencement tn- may book, Is on sale now In the Stu- in the Bee is I ' s .1 stru,ti011,1 dent Affairs business office and .tdiftlUS. an front of the Spartan book - Instructions I''. 51541111 ii det II More fur sfi.rai. shat is expected of graduates "Only 2100 copies were print- fur OW esendse, to be ed this year," said George Mead - hrid June 10 in Spartan (MN, La Torn- publicity mans- attatt grr. Stadium. SAN JOSE STATE COLLEGE VOL 47 41,00 SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA, FRIDAY, APRIL 22, 1960 NO. 112 One Will Be Queen -Music Festival Boasts Housing Rule Lively New Revelries Original Compositions Discussion rays la Ti)ttnpablislmJ1 niusie MUMI 1957 to provide an opportunity for I Again Tonight composition.s will be performed by unpublished works to be per- San Jose State music groups at formed and to promote Music com- Set Monday By GERALD NAi Stir SN who puts over the Lund-Papson third annual Contemporary positions for high the school and col- Drains Editor songs with a professional touch , festival in Concert Hall lege music Necessity and effect of the new Music groups. and does one of the better acting Dr. Gibson Walters, [lousing rule for next fall will be A melodically alive and lavish today. professor of jobs in the show. Compositions for the all -day music, will direct the orchestra discussed by Robert L. Baron, 1960 Revelries, "Innocence and In- prognirn will be presented by band, performance, and William Erlend- tmusing coordinator, Monday in solence," while bogged down in a Male lead, Lee Wolfram, how- choral and chamber en- son, orchestra, professor of music, will con- C11240 at 7:30 p.m. -

Copy of BOGGIE

BOGGIE is one of the top talents and internationally most renowned singers of the Hungarian music scene. HIGHLIGHTS from Billboard to Eurovision Her first album titled Boggie (2013) was No.3 on the Billboard chart in 2014 February. Her videoclip titled "Parfum" gained a really significant international interest, reaching 30 million views. In 2015 she won the Hungarian national competition titled "A Dal 2015". As a result of that she represented Hungary at the 2015 Eurovision Song Contest. in 2018 she was the only Hungarian female artist among the SXSW artists In 2016 she took a brief break from her music career due to SINGER- giving birth to her daughter and in 2017 she’s back with a new self-published, trilingual album with songs in Hungarian, French SONGWRITER and English. Boggie is solely responsible for all the songwriting on the album. The birth of her daughter has admittedly changed Music Styles her songwriting, she sounds much more confident and as a result, the new album is excitingly diverse. Boggie's musical world is a great mixture of classical music, jazz, it even has some world music elements and a huge influence from French pop music. 2013 Frankfurt Light & Buliding GE References 2013 Sunset & Sunside Jazz Club PARIS INTERNATIONAL 2014 Munich Creative Camp 2015 First EUROPEAN TOUR CARREER ( Lille, Bruxelles, Paris, Madrid, Bilbao, Marseille) In 2015 in the Viennese Opera she performed at a concert titled "Pop 2015 BILBAO MUSIC FESTIVAL meets Opera" that featured Juan Diego 2015 New York Hofstra University, Phoenix Flórez too. 2016 New York PIANOS, Miami 2018 SXSW Festival AUSTIN 2018 MIAMI CubaOcho Museum INSTRUMENTS All the musicians in Boggie's band including Boggie herself, got a high level qualification in THE BAND classical music and jazz music. -

BUDAPESTI GAZDASÁGI FŐISKOLA KÜLKERESKEDELMI FŐISKOLAI KAR Nappali Tagozat Szakdiplomácia Szakirány AZ EUROVÍZIÓS DALFES

http://www.doksi.hu BUDAPESTI GAZDASÁGI FŐISKOLA KÜLKERESKEDELMI FŐISKOLAI KAR GAZDASÁGDIPLOMÁCIA ÉS NEMZETKÖZI MENEDZSMENT SZAK Nappali tagozat Szakdiplomácia szakirány AZ EUROVÍZIÓS DALFESZTIVÁL, MINT MEGARENDEZVÉNY L EBONYOLÍTÁSA ÉS SZEREPE A NEMZETKÖZI KAPCSOLATOKBAN Készítette: Szentgyörgyvölgyi Éva Budapest, 2009 http://www.doksi.hu T ARTALOMJEGYZÉK Tartalomjegyzék .......................................................................................................3 Témaválasztás és bevezetés ......................................................................................6 I. Az Eurovíziós Dalfesztivál bemutatása ...............................................................7 1. Az Eurovíziós Dalfesztivál ötletének történelmi háttere .....................................7 2. Az Európai Műsorszolgáltatók Szövetségének (EBU) létrehozása.....................8 3. Kicsit bővebben az EBU szervezetéről................................................................9 4. Az Eurovíziós Dalfesztivál ................................................................................11 4.1. A Dalfesztivál alakulása 1956-tól napjainkig .........................................................12 4.1.1. A szavazás......................................................................................................12 4.1.2. A versenydallal kapcsolatos szabályok..........................................................14 4.1.3. A részvétellel kapcsolatos szabályok .............................................................16 4.1.4. A Dalfesztivál -

Official Journal of the European Union

Official Journal C 175 of the European Union Volume 63 English edition Information and Notices 25 May 2020 Contents IV Notices NOTICES FROM EUROPEAN UNION INSTITUTIONS, BODIES, OFFICES AND AGENCIES Court of Justice of the European Union 2020/C 175/01 Last publications of the Court of Justice of the European Union in the Official Journal of the European Union . 1 Court of Justice 2020/C 175/02 Taking of the oath by a new Member . 2 V Announcements COURT PROCEEDINGS Court of Justice 2020/C 175/03 Case C-87/20: Request for a preliminary ruling from the Bundesfinanzhof (Germany) lodged on 19 February 2020 — Hauptzollamt B v XY . 3 2020/C 175/04 Case C-95/20: Request for a preliminary ruling from the Administrativen sad Varna (Bulgaria) lodged on 25 February 2020 — VARCHEV FINANS EOOD v Komisia za finansov nadzor . 4 EN 2020/C 175/05 Case C-105/20: Request for a preliminary ruling from the Tribunal du travail de Nivelles (Belgium) lodged on 27 February 2020 — UF v Union Nationale des Mutualités Libres (Partenamut) (UNMLibres) . 5 2020/C 175/06 Case C-122/20 P: Appeal brought on 21 February 2020 by Bruno Gollnisch against the judgment of the General Court (Fifth Chamber) delivered on 10 December 2019 in Case T-319/19 Bruno Gollnisch v European Parliament . 6 2020/C 175/07 Case C-125/20: Action brought on 4 March 2020 — European Commission v Kingdom of Spain . 6 General Court 2020/C 175/08 Case T-732/16: Judgment of the General Court of 12 March 2020 — Valencia Club de Fútbol v Commission (State aid — Aid granted by Spain to certain professional football clubs — Guarantee — Decision declaring the aid to be incompatible with the internal market — Advantage — Firm in difficulty — Private investor test — Guidelines on State aid for rescuing and restructuring firms in difficulty — Amount of the aid — Recipient of the aid — Principle of non-discrimination — Duty to state reasons) . -

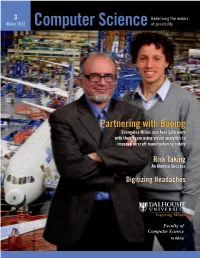

Partnering with Boeing Evangelos Milios and Axel Soto Work with Their Team Using Visual Analytics to Improve Aircraft Manufacturing Safety

2 3 RedefiningRedefining the the realms realms SpringWInter 2011 2012 Computer Scienceof possibilityof possibility Partnering with Boeing Evangelos Milios and Axel Soto work with their team using visual analytics to improve aircraft manufacturing safety Risk Taking An Alumna Success Digitizing Headaches Faculty of Computer Science cs.dal.ca 2 Computer Science We live in a global economy and Canadian universities are not immune from this Visual Analytics Researchin Computer Science phenomenon. In response, Dalhou- sie has placed a new emphasis on A major project is underway collaboration with international insti- in the Faculty of Computer tutions. So, where does the Faculty of Science in Visual Analytics, Computer Science fit in all of this? funded by the Boeing In the past year, the Faculty of Company. The project, Computer Science has signed a 2+2 started in October 2010, is MOU with one Chinese university and led by principal investigator has three more such agreements in Evangelos Milios and con- the final stages of negotiations. A sists of two parts, Visual 2+2 means that the students take Text Analytics (over 5 years) their first two years at their home and Mobile Graphics (over university and come to us for their 3 years). final two years, receiving their BCSc or BINF from Dalhousie. Visual Text Analytics We have just signed an MOU Visual text analytics aims with King Saud University (KSU) in to advance the state of Riyadh for their graduates to come the art in sense-making of to us for Masters, PhD and Post- large document corpora. Doctoral studies.