Arxiv:1912.10250V1 [Math.DS] 21 Dec 2019 the flow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AR 96 Covers/Contents

ICTP FULL TECHNICAL REPORT 2018 INTRODUCTION This document is the full technical report of ICTP for the year 2018. For the non-technical description of 2018 highlights, please see the printed “ICTP: A Year in Review” publication. 2 ICTP Full Technical Report 2018 CONTENTS Research High Energy, Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics (HECAP) ........................................................................ 7 Director's Research Group – String Phenomenology and Cosmology ...................................... 30 Condensed Matter and Statistical Physics (CMSP)............................................................................................ 32 Sustainable Energy Synchrotron Radiation Related Theory Mathematics ........................................................................................................................................................................ 63 Earth System Physics (ESP) ......................................................................................................................................... 71 Applied Physics Multidisciplinary Laboratory (MLab) ....................................................................................................... 97 Telecommunications/ICT for Development Laboratory (T/ICT4D) ....................................... 108 Medical Physics ................................................................................................................................................. 113 Fluid Dynamics .................................................................................................................................................. -

BILLIARDS in REGULAR 2N-GONS and the SELF-DUAL INDUCTION

BILLIARDS IN REGULAR 2n-GONS AND THE SELF-DUAL INDUCTION SEBASTIEN´ FERENCZI Abstract. We build a coding of the trajectories of billiards in regular 2n-gons, similar but different from the one in [16], by applying the self-dual induction [9] to the underlying one-parameter family of n-interval exchange transformations. This allows us to show that, in that family, for n = 3 non-periodicity is enough to guarantee weak mixing, and in some cases minimal self-joinings, and for every n we can build examples of n-interval exchange transformations with weak mixing, which are the first known explicitly for n > 6. In [16], see also [15], John Smillie and Corinna Ulcigrai develop a rich and original theory of billiards in the regular octagons, and more generally of billiards in the regular 2n-gons, first studied by Veech [17]: their aim is to build explicitly the symbolic trajectories, which generalize the famous Sturmian sequences (see for example [1] among a huge literature), and they achieve it through a new renormalization process which generalizes the usual continued fraction algorithm. In the present shorter paper, we show that similar results, with new consequences, can be obtained by using an existing, though recent, theory, the self-dual in- duction on interval exchange transformations. As in [16], we define a trajectory of a billiard in a regular 2n-gon as a path which starts in the interior of the polygon, and moves with constant velocity until it hits the boundary, then it re-enters the polygon at the corresponding point of the parallel side, and continues travelling with the same velocity; we label each pair of parallel sides with a letter of the alphabet (A1; :::An), and read the labels of the pairs of parallel sides crossed by the trajectory as time increases; studying these trajectories is known to be equivalent to studying the trajectories of a one-parameter family of n-interval exchange transformations, and to this family we apply a slightly modified version of the self-dual induction defined in [9]. -

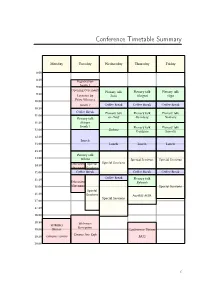

Conference Timetable Summary

Conference Timetable Summary Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday 8:00 8:30 Registration 9:00 South 1 Opening Ceremony Plenary talk Plenary talk Plenary talk 9:30 Lectures by Joshi Ulcigrai Giga 10:00 Prize Winners South 1 Coffee Break Coffee Break Coffee Break 10:30 Coffee Break Plenary talk Plenary talk Plenary talk 11:00 Plenary talk an Huef Steinberg Norbury 11:30 Krieger South 1 Plenary talk Plenary talk 12:00 Debate Trudgian Samotij 12:30 Lunch 13:00 Lunch Lunch Lunch 13:30 Plenary talk 14:00 Sikora Special Sessions Special Sessions Special Sessions 14:30 Education Special Afternoon Sessions 15:00 Coffee Break Coffee Break Coffee Break Coffee Break 15:30 Plenary talk Education Rylands 16:00 Afternoon Special Sessions Special 16:30 Sessions AustMS AGM Special Sessions 17:00 17:30 18:00 18:30 Welcome WIMSIG Reception 19:00 Dinner Conference Dinner Cinque Lire Cafe 19:30 Campus Centre MCG 20:00 1 Contents Foreword 4 Conference Sponsors 5 Conference Program 6 Education Afternoon 7 Session 1: Plenary Lectures 8 Special Sessions 2. Algebra 9 3. Applied and Industrial Mathematics 10 4. Category Theory 11 5. Combinatorics and Graph Theory 12 6. Computational Mathematics 14 7. Dynamical Systems and Ergodic Theory 15 8. Financial mathematics 16 9. Functional Analysis, Operator Algebra, Non-commutative Geometry 17 10. Geometric Analysis and Partial Differential Equations 18 11. Geometry including Differential Geometry 20 12. Harmonic and Semiclassical Analysis 21 13. Inclusivity, diversity, and equity in mathematics 22 14. Mathematical Biology 23 15. Mathematics Education 24 16. Mathematical Physics, Statistical Mechanics and Integrable systems 25 17. -

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Dynamische Systeme

Mathematisches Forschungsinstitut Oberwolfach Report No. 32/2017 DOI: 10.4171/OWR/2017/32 Dynamische Systeme Organised by Hakan Eliasson, Paris Helmut Hofer, Princeton Vadim Kaloshin, College Park Jean-Christophe Yoccoz, Paris 9 July – 15 July 2017 Abstract. This workshop continued the biannual series at Oberwolfach on Dynamical Systems that started as the “Moser-Zehnder meeting” in 1981. The main themes of the workshop are the new results and developments in the area of dynamical systems, in particular in Hamiltonian systems and symplectic geometry. This year special emphasis where laid on symplectic methods with applications to dynamics. The workshop was dedicated to the memory of John Mather, Jean-Christophe Yoccoz and Krzysztof Wysocki. Mathematics Subject Classification (2010): 37, 53D, 70F, 70H. Introduction by the Organisers The workshop was organized by H. Eliasson (Paris), H. Hofer (Princeton) and V. Kaloshin (Maryland). It was attended by more than 50 participants from 13 countries and displayed a good mixture of young, mid-career and senior people. The workshop covered a large area of dynamical systems centered around classi- cal Hamiltonian dynamics and symplectic methods: closing lemma; Hamiltonian PDE’s; Reeb dynamics and contact structures; KAM-theory and diffusion; celes- tial mechanics. Also other parts of dynamics were represented. K. Irie presented a smooth closing lemma for Hamiltonian diffeomorphisms on closed surfaces. This result is the peak of a fantastic development in symplectic methods where, in particular, the contributions of M. Hutchings play an important role. 1988 Oberwolfach Report 32/2017 D. Peralta-Salas presented new solutions for the 3-dimensional Navier-Stokes equations with different vortex structures. -

Scientific Workplace· • Mathematical Word Processing • LATEX Typesetting Scientific Word· • Computer Algebra

Scientific WorkPlace· • Mathematical Word Processing • LATEX Typesetting Scientific Word· • Computer Algebra (-l +lr,:znt:,-1 + 2r) ,..,_' '"""""Ke~r~UrN- r o~ r PooiliorK 1.931'J1 Po6'lf ·1.:1l26!.1 Pod:iDnZ 3.881()2 UfW'IICI(JI)( -2.801~ ""'"""U!NecteoZ l!l!iS'11 v~ 0.7815399 Animated plots ln spherical coordln1tes > To make an anlm.ted plot In spherical coordinates 1. Type an expression In thr.. variables . 2 WMh the Insertion poilt In the expression, choose Plot 3D The next exampfe shows a sphere that grows ftom radius 1 to .. Plot 3D Animated + Spherical The Gold Standard for Mathematical Publishing Scientific WorkPlace and Scientific Word Version 5.5 make writing, sharing, and doing mathematics easier. You compose and edit your documents directly on the screen, without having to think in a programming language. A click of a button allows you to typeset your documents in LAT£X. You choose to print with or without LATEX typesetting, or publish on the web. Scientific WorkPlace and Scientific Word enable both professionals and support staff to produce stunning books and articles. Also, the integrated computer algebra system in Scientific WorkPlace enables you to solve and plot equations, animate 20 and 30 plots, rotate, move, and fly through 3D plots, create 3D implicit plots, and more. MuPAD' Pro MuPAD Pro is an integrated and open mathematical problem solving environment for symbolic and numeric computing. Visit our website for details. cK.ichan SOFTWARE , I NC. Visit our website for free trial versions of all our products. www.mackichan.com/notices • Email: info@mac kichan.com • Toll free: 877-724-9673 It@\ A I M S \W ELEGRONIC EDITORIAL BOARD http://www.math.psu.edu/era/ Managing Editors: This electronic-only journal publishes research announcements (up to about 10 Keith Burns journal pages) of significant advances in all branches of mathematics. -

Donwload All Abstracts

INdAM Meeting: Hyperbolic Dynamical Systems in the Sciences Corinaldo (Italy) May 31 - June 4, 2010 ABSTRACTS Viviane Baladi (Ecole Normale Sup´erieure,Paris) Anisotropic Sobolev spaces adapted to piecewise hyperbolic dynamics Strong ergodic properties (such as exponential mixing) have been proved for various smooth dynamical systems by first obtaining a spectral gap for a suitable \transfer" operator acting on an appropriate Banach space. Some natural dynamical systems, such as discrete or continuous-time billiards, are only piecewise smooth, and the discontinuities pose serious technical problems in the construction of the Banach norm. With Sebastien Gouezel (J. Mod. Dyn. 2010), we recently showed that classical tools such as complex interpolation on anisotropic Sobolev-Triebel spaces, and an old result of Strichartz on Fourier multipliers, can solve those problems, under a bunching condition. (The bunching condition replaces a smoothness assumption on the stable bundles which was necessary in a previous work.) I will also very briefly mention work in progress with Balint and Gouezel on the one hand, and Liverani on the other hand, the ultimate goal of which is to establish exponential mixing for continuous-time 2-d Sinai billiards. Peter´ Balint´ (Budapest University of Technology and Economics) Dispersing billiards with cusps and tunnels Two dimensional dispersing billiards with finite horizon and disjoint scatterers are among the best known examples of strongly chaotic dynamical systems. If, however, two scatterers of the configuration touch tangentially, forming a cusp, the billiard particle may experience arbitrary long sequences of successive collisions in the resulting region, which may slow down the convergence to equilibrium. The situation when the two scatterers do not actually touch, their distance is, however, some small ", may be referred to as a billiard with a tunnel. -

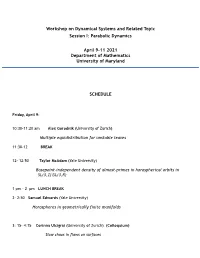

Parabolic Dynamics April 9-11 2021 Department of Mathematics Universi

Workshop on Dynamical Systems and Related Topic Session I: Parabolic Dynamics April 9-11 2021 Department of Mathematics University of Maryland SCHEDULE Friday, April 9: 10:30-11:20 am Alex Gorodnik (University of Zurich) Multiple equidistribution for unstable leaves 11:30-12 BREAK 12- 12:50 Taylor McAdam (Yale University) Basepoint-independent density of almost-primes in horospherical orbits in SL(3,Z)\SL(3,R) 1 pm - 2 pm LUNCH BREAK 2- 2:50 Samuel Edwards (Yale University) Horospheres in geometrically finite manifolds 3: 15- 4:15 Corinna Ulcigrai (University of Zurich) (Colloquium) Slow chaos in flows on surfaces Saturday, April 10: 10:30 - 11:20 am Zhiren Wang (Penn State University) Möbius disjointness for almost reducible analytic quasi-periodic cocycles 11:30 - 12 BREAK 12 - 12:50 Kurt Vinhage (Penn State University) Classification and complexity for unipotent group actions 1 - 2 pm LUNCH BREAK 2 - 4:30 Brin Prize session 2 - 2:15 Presentation of the Award 2: 15 - 3:15 Mariusz Lemanczyk Spectral theory, Ratner's properties and Furstenberg disjointness 3:30-4:30 Stefano Marmi Some arithmetical aspects of renormalization in Teichmuller dynamics Sunday, April 11: 10:00 -10:50 am Maria Isabel Cortez (Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile) Classification of group actions on the Cantor set 11-11:20 BREAK 11:20 - 11:50 Shrey Sanadhya (University of Iowa) Substitution on infinite alphabet and generalized Bratteli-Vershik model. 12 - 12:50 pm Dmitri Scheglov (Universidade Federal Fluminense) Ergodic properties of G-extensions over translation flows and IETs ABSTRACTS María Isabel Cortez Title: Classification of group actions on the Cantor set Abstract: Every countable group admits continuous actions on the Cantor set. -

Abstracts of Talks Joint Meeting of the Italian Mathematical Union, the Italian Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics and the Polish Mathematical Society

Abstracts of talks Joint meeting of the Italian Mathematical Union, the Italian Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics and the Polish Mathematical Society Wrocław, 17-20 September 2018 MAIN ORGANIZERS CO-ORGANIZERS SPONSORS Contents I Conference Information Conference Schedule.................................................... 13 II Plenary Lectures Plenary Speakers......................................................... 17 Guest Plenary Speaker.................................................... 22 III Sessions 1 Model Theory......................................................... 25 2 Number Theory........................................................ 31 3 Projective Varieties and their Arrangements............................... 37 4 Algebraic Geometry................................................... 43 5 Algebraic Geometry and Interdisciplinary Applications..................... 47 6 Arithmetic Algebraic Geometry......................................... 53 7 Group Theory......................................................... 59 8 Geometric Function and Mapping Theory................................ 71 9 Complex Analysis and Geometry........................................ 77 10 Optimization, Microstructures, and Applications to Mechanics.............. 81 11 Variational and Set-valued Methods in Differential Problems................ 89 12 Topological Methods and Boundary Value Problems...................... 95 13 Variational Problems and Nonlinear PDEs............................... 103 14 Nonlinear Variational Methods -

Of the American Mathematical Society June/July 2018 Volume 65, Number 6

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society June/July 2018 Volume 65, Number 6 James G. Arthur: 2017 AMS Steele Prize for Lifetime Achievement page 637 The Classification of Finite Simple Groups: A Progress Report page 646 Governance of the AMS page 668 Newark Meeting page 737 698 F 659 E 587 D 523 C 494 B 440 A 392 G 349 F 330 E 294 D 262 C 247 B 220 A 196 G 145 F 165 E 147 D 131 C 123 B 110 A 98 G About the Cover, page 635. 2020 Mathematics Research Communities Opportunity for Researchers in All Areas of Mathematics How would you like to organize a weeklong summer conference and … • Spend it on your own current research with motivated, able, early-career mathematicians; • Work with, and mentor, these early-career participants in a relaxed and informal setting; • Have all logistics handled; • Contribute widely to excellence and professionalism in the mathematical realm? These opportunities can be realized by organizer teams for the American Mathematical Society’s Mathematics Research Communities (MRC). Through the MRC program, participants form self-sustaining cohorts centered on mathematical research areas of common interest by: • Attending one-week topical conferences in the summer of 2020; • Participating in follow-up activities in the following year and beyond. Details about the MRC program and guidelines for organizer proposal preparation can be found at www.ams.org/programs/research-communities /mrc-proposals-20. The 2020 MRC program is contingent on renewed funding from the National Science Foundation. SEND PROPOSALS FOR 2020 AND INQUIRIES FOR FUTURE YEARS TO: Mathematics Research Communities American Mathematical Society Email: [email protected] Mail: 201 Charles Street, Providence, RI 02904 Fax: 401-455-4004 The target date for pre-proposals and proposals is August 31, 2018. -

Curriculum Vitae of Corinna Ulcigrai

Curriculum vitae of Corinna Ulcigrai Date of birth: January 3, 1980, Trieste (Italy) Sex: Female Personal: Married to Alexander Gorodnik, 2 children Citizenship: Italian and British Residence: Switzerland Work Address: Institute f¨urMathematik, University of Z¨urich office K36 Y27, Winterthurerstrasse 190, 8057 Z¨urich, Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Academic Qualifications 2002 - 2007 Princeton University, Deparment of Mathematics Degree: Ph.D. (June 2007) Thesis Advisor Prof. Ya. G. Sinai (Abel Prize 2014) 1998 - 2002 Scuola Normale Superiore and University of Pisa Degrees: Scuola Normale "`Diploma"' (70/70 cum laude, July 2002) Laurea in Mathematics (110/110 cum laude, June 2002) Thesis Advisor: Prof. S. Marmi (Scuola Normale Superiore). Present Positions Aug 2018{ Full Professor at the Mathematics Institute of the University of Z¨urich Past Academic Positions Aug 2015{July 2019 University of Bristol, Professor in Pure Mathematics Aug 2013{Jul 2015 University of Bristol, Reader in Pure Mathematics Aug 2007{Jul 2013 University of Bristol, Lecturer and Research Fellow Jan 2008{Apr 2008 Institute for Advanced Studies, Princeton NJ, USA, Postdoctoral Member, Petronio Felloship Aug 2007{Dec 2007 MSRI, Berkeley CA, USA Postdoctoral Member, MSRI Fellowship Awards and Honors • Royal Society Wolfson Research Merit Award 2017 • Philip Leverhulme Prize 2014, awarded by the Leverhulme Trust • Whitehead Prize 2013, awarded by the London Mathematical Society • ERC Starting Grant holder, from January 2014 • European Mathematical Society Prize (2012), awarded at the 12th European Mathematical Congress • RCUK Fellowship (UK Research Council) (2007-2012) • 2007 Clay Liftoff Fellowship • Centennial Fellowship from the Graduate School at Princeton University (2002-2007) Curriculum Vitae Corinna Ulcigrai Grants • SNSF (Swiss National Science Foundation) Project Grant Principle Investigator Ergodic and spectral properties of surface flows, September 2020 - August 2024. -

Dynamical Systems and Ergodic Theory

MATH36206 - MATHM6206 Dynamical Systems and Ergodic Theory Teaching Block 1, 2015/16 Lecturers: Prof. Corinna Ulcigrai and Dr. Thomas Jordan Lecture notes by Prof. Corinna Ulcigrai PART I OF III course web site: http://www.maths.bris.ac.uk/ maxcu/DSET/index.html ∼ Copyright c University of Bristol 2010 & 2016. This material is copyright of the University. It is provided exclusively for educational purposes at the University and is to be downloaded or copied for your private study only. Chapter 1 Examples of dynamical systems 1.1 Introduction Dynamical systems is an exciting and very active field in pure and applied mathematics, that involves tools and techniques from many areas such as analyses, geometry and number theory and has applications in many fields as physics, astronomy, biology, meterology, economics. The adjective dynamical refers to the fact that the systems we are interested in is evolving in time. In applied dynamics the systems studied could be for example a box containing molecules of gas in physics, a species population in biology, the financial market in economics, the wind currents in metereology. In pure mathematics, a dynamical system can be obtained by iterating a function or letting evolve in time the solution of equation. Discrete dynamical systems are systems for which the time evolves in discrete units. For example, we could record the number of individuals of a population every year and analyze the growth year by year. The time is parametrized by a discrete variable n which assumes integer values: we will denote natural numbers by N and integer numbers by Z. -

Angels' Staircases, Sturmian Sequences, And

JOURNALOF MODERN DYNAMICS doi: 10.3934/jmd.2020005 VOLUME 16, 2020, 109–153 ANGELS’ STAIRCASES, STURMIAN SEQUENCES, AND TRAJECTORIES ON HOMOTHETY SURFACES JOSHUA P. BOWMAN AND SLADE SANDERSON (Communicated by Corinna Ulcigrai) ABSTRACT. A homothety surface can be assembled from polygons by identi- fying their edges in pairs via homotheties, which are compositions of transla- tion and scaling. We consider linear trajectories on a 1-parameter family of genus-2 homothety surfaces. The closure of a trajectory on each of these sur- faces always has Hausdorff dimension 1, and contains either a closed loop or a lamination with Cantor cross-section. Trajectories have cutting sequences that are either eventually periodic or eventually Sturmian. Although no two of these surfaces are affinely equivalent, their linear trajectories can be related directly to those on the square torus, and thence to each other, by means of explicit functions. We also briefly examine two related families of surfaces and show that the above behaviors can be mixed; for instance, the closure of a linear trajectory can contain both a closed loop and a lamination. 1. INTRODUCTION A homothety of the plane is a similarity that preserves directions; in other words, it is a composition of translation and scaling. A homothety surface has an atlas, covering all but a finite set of points, whose transition maps are homo- theties. Homothety surfaces (also called dilation surfaces by some authors) are thus generalizations of translation surfaces, which have been actively studied for some time under a variety of guises (measured foliations, abelian differentials, unfolded polygonal billiard tables, etc.).