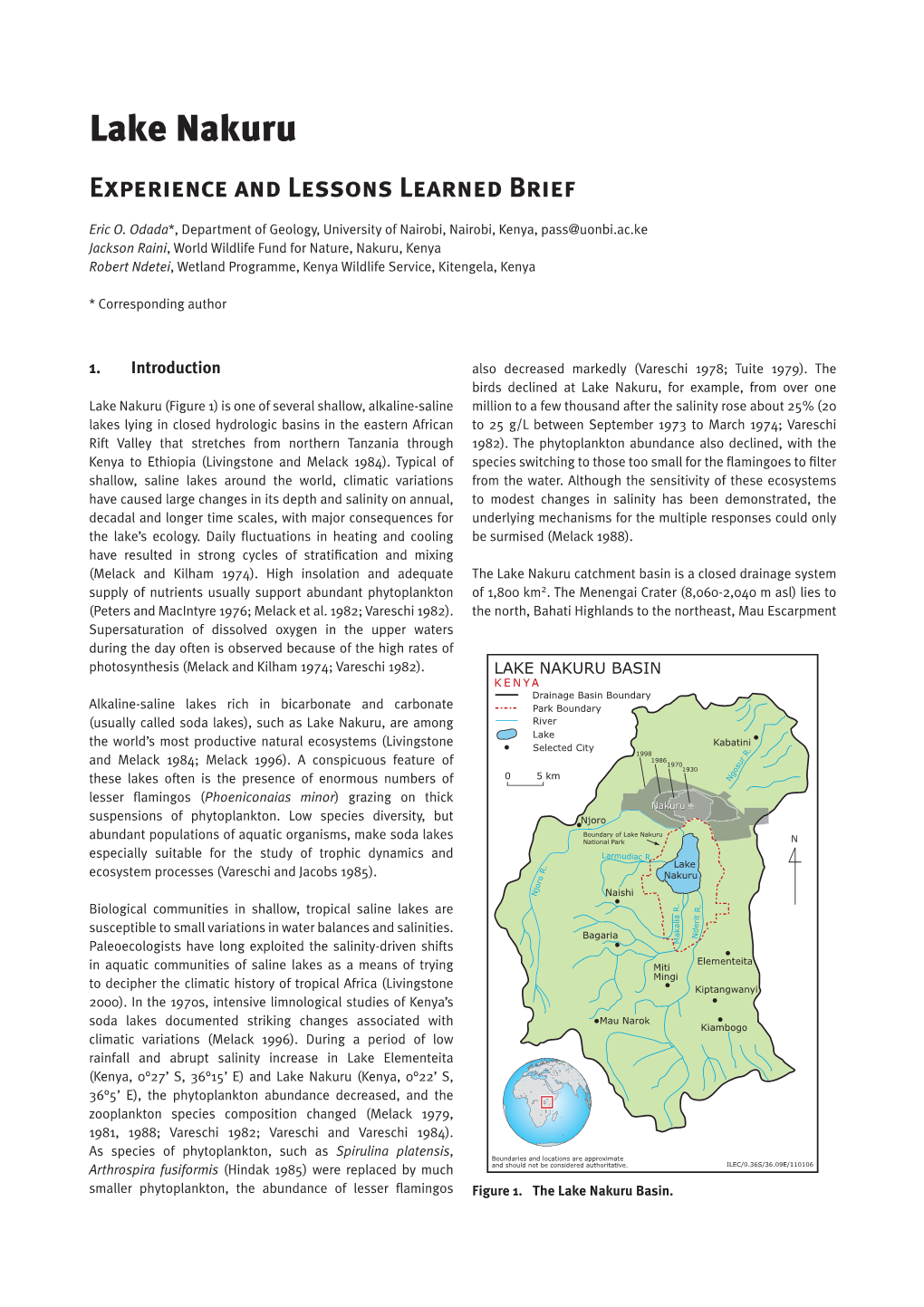

Lake Nakuru Experience and Lessons Learned Brief

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nakuru County

Kenya County Climate Risk Profile Nakuru County Map Book Contents Agro-Ecological Zones Baseline Map ………………….…………………………………………………………... 1 Baseline Map ………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………... 2 Elevation Map ...…………………….……………………………………………………………………………………..... 3 Farming Systems Map ……………….…….…………………………………………………………………………...... 4 Land Cover Map …………...……………………………………………………………………………………………...... 5 Livestock Production Systems Map ..…………………………………………………………………………......... 6 Mean Precipitation Map ……………….……………………………………………………………………………....... 7 Mean Temperature Map ……………………………………………………………………………………………....... 8 Population Density Map .………………………………………………………………………….…………………...... 9 Satellite Map .……………………………………………………………..………………………………………………... 10 Soil Classes Map ..……………………………………………………………………………………………..………...... 11 Travel Time Map ……………….…………………………………………………………………………………..…...... 12 AGRO-ECOLOGICAL ZONES a i o p ! ! i ! g ! ! ! k ! n i ! i ! ! ! ! r ! ! ! a ! ! a L ! ! !! ! ! ! ! B ! ! Solai ! ! ! ! Subukia ! ! ! ! ! ! Athinai ! ! ! ! Moto ! ! Bahati ! ! Rongai Kabarak N ! ! ! Menengai ! ! ! ! y Molo ! ! Dondori ! Turi ! a ! Nakuru ! ! ! Keusa Lanet Kio ! Elburgon ! ! ! Sasamua ! ! Chesingele Njoro n ! ! ! d N a k u r u ! ! ! ! Keringet ! a Kiriri ! Kariandusi ! Mukuki ! ! Elmentaita r Kabsege ! Gilgil ! ! Likia ! u East Mau ! ! ! a Olenguruone Mau ! ! F Cheptwech ! Narok ! ! ! Ambusket ! ! ! Morendat ! ! ! ! Naivasha ! ! Marangishu ! ! ! ! Ngunyumu Kangoni ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Longonot ! ! ! u ! ! ! b Akira Mai ! ! ! Legend ! Mahiu N a r o k ! m ! Town ! Agro-ecological -

Hydrologic Analysis of Malewa Watershed

HYDROLOGIC ANALYSIS OF MALEWA WATERSHED AS A BASIS FOR IMPLEMENTING PAYMENT FOR ENVIRONMENTAL SERVICES (PES) PHILIP LUKE OGWENO MASTER OF SCIENCE (Soil and Water Engineering) JOMOKENYATTA UNIVERSITY OF AGRICULTURE AND TECHNOLOGY 2009 Hydrologic Analysis of Malewa Watershed as a basis for Implementing Payment for Environmental Services (PES) Ogweno Luke Philip A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment for the Degree of Masters of Science in Soil and Water Engineering in the Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology. 2009 ii DECLARATION This thesis is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University Signature ………………….. Date…………...... Ogweno Luke Philip This thesis has been submitted for examination with our approval university supervisors 1. Signature …………… Date…….……… Dr J. M. Gathenya JKUAT, KENYA 2. Signature…………….. Date………………… Dr. P.G. Home JKUAT, KENYA i DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my late father John Alfred Ondulo Aduda for his inspiration and mentorship. The discipline towards work that you instilled in me will live and I will propagate your legacy for the rest of my life, rest in peace. It is also dedicated to all who are struggling to conserve and preserve the environment for the future progeny, to my family members and Cecilia Anyango. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The success of this project owes much to the constant and helpful supervision given by Dr. J.M. Gathenya and Dr. P.G. Home, senior lecturers at the Department of Biomechanical and Environmental Engineering, Jomo Kenyatta University. Their guidance in getting research materials/project and encouragement throughout the course contributed constructively towards the success of this project. -

Historical Volcanism and the State of Stress in the East African Rift System

Historical volcanism and the state of stress in the East African Rift System Article Accepted Version Open Access Wadge, G., Biggs, J., Lloyd, R. and Kendall, J.-M. (2016) Historical volcanism and the state of stress in the East African Rift System. Frontiers in Earth Science, 4. 86. ISSN 2296- 6463 doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/feart.2016.00086 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/66786/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/feart.2016.00086 Publisher: Frontiers media All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 1 Historical volcanism and the state of stress in the East African 2 Rift System 3 4 5 G. Wadge1*, J. Biggs2, R. Lloyd2, J-M. Kendall2 6 7 8 1.COMET, Department of Meteorology, University of Reading, Reading, UK 9 2.COMET, School of Earth Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK 10 11 * [email protected] 12 13 14 Keywords: crustal stress, historical eruptions, East African Rift, oblique motion, 15 eruption dynamics 16 17 18 19 20 21 Abstract 22 23 Crustal extension at the East African Rift System (EARS) should, as a tectonic ideal, 24 involve a stress field in which the direction of minimum horizontal stress is 25 perpendicular to the rift. -

469880Esw0whit10cities0rep

Report No. 46988 Public Disclosure Authorized &,7,(62)+23(" GOVERNANCE, ECONOMIC AND HUMAN CHALLENGES OF KENYA’S FIVE LARGEST CITIES Public Disclosure Authorized December 2008 Water and Urban Unit 1 Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank __________________________ This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without written authorization from the World Bank. ii PREFACE The objective of this sector work is to fill existing gaps in the knowledge of Kenya’s five largest cities, to provide data and analysis that will help inform the evolving urban agenda in Kenya, and to provide inputs into the preparation of the Kenya Municipal Program (KMP). This overview report is first report among a set of six reports comprising of the overview report and five city-specific reports for Nairobi, Mombasa, Kisumu, Nakuru and Eldoret. The study was undertaken by a team comprising of Balakrishnan Menon Parameswaran (Team Leader, World Bank); James Mutero (Consultant Team Leader), Simon Macharia, Margaret Ng’ayu, Makheti Barasa and Susan Kagondu (Consultants). Matthew Glasser, Sumila Gulyani, James Karuiru, Carolyn Winter, Zara Inga Sarzin and Judy Baker (World Bank) provided support and feedback during the entire course of work. The work was undertaken collaboratively with UN Habitat, represented by David Kithkaye and Kerstin Sommers in Nairobi. The team worked under the guidance of Colin Bruce (Country Director, Kenya) and Jamie Biderman (Sector Manager, AFTU1). The team also wishes to thank Abha Joshi-Ghani (Sector Manager, FEU-Urban), Junaid Kamal Ahmad (Sector Manager, SASDU), Mila Freire (Sr. -

Citizen Participation in County Integrated Development Planning and Budgeting Processes in Kenya

A Report of Trócaire Kenya A Report of Trócaire Kenya Citizen participation in County Integrated Development Planning and budgeting processes in Kenya A case of five Counties A Report of Trócaire Kenya Acknowledgements This research project was commissioned by Trócaire Kenya, and our sincere gratitude goes to all those who contributed towards its success. Special thanks to the respondents from the project areas for their co-operation and input. The contribution by respondents from The County Government, The National Government, communities, civil society and all other stakeholders interviewed is highly appreciated. Recognition goes to the support received from the government of Ireland through Irish Aid for their continued contribution to Trócaire’s work and supporting this research. © Trócaire, Kenya, 2019 2 Table of Contents A Report of Trócaire Kenya 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 4 GLOSSARY 5 ABOUT TRÓCAIRE 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 10 BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION 13 INTEGRATED PLANNING & BUDGETING AND PUBLIC PARTICIPATION AND PRACTICE 20 STUDY FINDINGS 37 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS 3 Glossary ADP Annual Development Plan AG Attorney General CBEF County Budget and Economic Forum CDB County Development Board CECM County Executive Committee Member CFSP County Fiscal Strategy Paper CGs County Governments CGA County Government Act CGA2012 County Government Act (2012) CIDP County Integrated Development Plan CIMES County Integrated Monitoring and Evaluation System CLIDP Community-Level Infrastructure Development Programme OCOB Office of Controller of Budget -

Lake Turkana and the Lower Omo the Arid and Semi-Arid Lands Account for 50% of Kenya’S Livestock Production (Snyder, 2006)

Lake Turkana & the Lower Omo: Hydrological Impacts of Major Dam & Irrigation Development REPORT African Studies Centre Sean Avery (BSc., PhD., C.Eng., C. Env.) © Antonella865 | Dreamstime © Antonella865 Consultant’s email: [email protected] Web: www.watres.com LAKE TURKANA & THE LOWER OMO: HYDROLOGICAL IMPACTS OF MAJOR DAM & IRRIGATION DEVELOPMENTS CONTENTS – VOLUME I REPORT Chapter Description Page EXECUTIVE(SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................................1! 1! INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 12! 1.1! THE(CONTEXT ........................................................................................................................................ 12! 1.2! THE(ASSIGNMENT .................................................................................................................................. 14! 1.3! METHODOLOGY...................................................................................................................................... 15! 2! DEVELOPMENT(PLANNING(IN(THE(OMO(BASIN ......................................................................... 18! 2.1! INTRODUCTION(AND(SUMMARY(OVERVIEW(OF(FINDINGS................................................................... 18! 2.2! OMO?GIBE(BASIN(MASTER(PLAN(STUDY,(DECEMBER(1996..............................................................19! 2.2.1! OMO'GIBE!BASIN!MASTER!PLAN!'!TERMS!OF!REFERENCE...........................................................................19! -

KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis

REPUBLIC OF KENYA KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS Kenya Population Situation Analysis Published by the Government of Kenya supported by United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce National Council for Population and Development (NCPD) P.O. Box 48994 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-271-1600/01 Fax: +254-20-271-6058 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ncpd-ke.org United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Kenya Country Oce P.O. Box 30218 – 00100, Nairobi, Kenya Tel: +254-20-76244023/01/04 Fax: +254-20-7624422 Website: http://kenya.unfpa.org © NCPD July 2013 The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the contributors. Any part of this document may be freely reviewed, quoted, reproduced or translated in full or in part, provided the source is acknowledged. It may not be sold or used inconjunction with commercial purposes or for prot. KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS JULY 2013 KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS i ii KENYA POPULATION SITUATION ANALYSIS TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................iv FOREWORD ..........................................................................................................................................ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ..........................................................................................................................x EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................xi -

Alcolapia Grahami ERSS

Lake Magadi Tilapia (Alcolapia grahami) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, March 2015 Revised, August 2017, October 2017 Web Version, 8/21/2018 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Bayona and Akinyi (2006): “The natural range of this species is restricted to a single location: Lake Magadi [Kenya].” Status in the United States No records of Alcolapia grahami in the wild or in trade in the United States were found. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has listed the tilapia Alcolapia grahami as a prohibited species. Prohibited nonnative species (FFWCC 2018), “are considered to be dangerous to the ecology and/or the health and welfare of the people of Florida. These species are not allowed to be personally possessed or used for commercial activities.” Means of Introductions in the United States No records of Alcolapia grahami in the United States were found. 1 Remarks From Bayona and Akinyi (2006): “Vulnerable D2 ver 3.1” Various sources use Alcolapia grahami (Eschmeyer et al. 2017) or Oreochromis grahami (ITIS 2017) as the accepted name for this species. Information searches were conducted under both names to ensure completeness of the data gathered. 2 Biology and Ecology Taxonomic Hierarchy and Taxonomic Standing According to Eschmeyer et al. (2017), Alcolapia grahami (Boulenger 1912) is the current valid name for this species. It was originally described as Tilapia grahami; it has also been known as Oreoghromis grahami, and as a synonym, but valid subspecies, of -

I. General Overview Development Partners Are Insisting on the Full

UNITED NATIONS HUMANITARIAN UPDATE vol. 40 6 November – 20 November 2008 Office of the United Nations Humanitarian Coordinator in Kenya HIGHLIGHTS • Donors pressure government on the implementation of Waki and Kriegler reports • Kenya Red Cross appeals for US$ 7. 5 million for 300,000 people requiring humanitarian aid due to recent flash floods, landslides and continued conflict • Kenyan military in rescue operation along Kenya-Somalia border The information contained in this report has been compiled by OCHA from information received from the field, from national and international humanitarian partners and from other official sources. It does not represent a position from the United Nations. This report is posted on: http://ochaonline.un.org/kenya I. General Overview Development partners are insisting on the full implementation of the Waki and Kriegler reports to facilitate further development and put an end to impunity. Twenty-five diplomatic missions in Nairobi, including the US, Canada and the European Union countries have piled pressure for the implementation of the report whose key recommendations was the setting up of a special tribunal to try the financiers, perpetrators and instigators of the violence that rocked the country at the beginning of this year. The European Union has threatened aid sanctions should the Waki Report not be implemented. An opinion poll by Strategic Research Limited found that 55.8 per cent of respondents supported the full implementation of the report on post-lection violence. On 19 November, Parliament moved to chart the path of implementing the Waki Report by forming two committees to provide leadership on the controversial findings. -

Case Study Report For

Case Study One Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in the Kenya Lake System in the Great Rift Valley 1 By DR. KANYINKE SENA Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in the Kenya Lake System in the Great Rift Valley 1 CASE STUDY ONE Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in the Kenya World Heritage (IIPFWH), as a standing global Lake System in the Great Rift Valley body aimed at representing indigenous peo- ples voices in the World Heritage Committee processes.5 The Committee referred to the establishment of the IIPFWH, “As an impor- tant reflection platform on the involvement of Indigenous Peoples in the identification, conservation and management of World Heritage properties, with a particular focus on the nomination process.” 6 Pursuant to the mandate of the Forum, this report aims at analyzing Indigenous Peoples’ involvement in the Kenya Lakes System in the Great Rift Valley World Heritage Site. The report is as result of extensive literature re- view and interviews with communities in and around the lakes that comprise the Kenya K. Sena: Lake Bogoria Lakes System. The Kenya Lake System in the Great Rift Val- ley is a World Heritage site in Kenya which comprises three inter-linked, relatively shal- low, alkaline lakes and their surrounding territories. The lakes system includes Lakes Elementeita, Nakuru and Bogoria in the Rift Valley. The lakes cover a total area of 32,034 and was inscribed as a world heritage site in 2011. The inscription was based on the lakes system outstanding universal values and criterion (vii), (ix) and (x) as provided for, under paragraph 77 of the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. -

Omenda Geothermal Heat Sources in East Africa Rift System 2016

Heat Sources for Geothermal Systems in East African Rift System Peter Omenda Classification by Temperature Volcano hosted Geothermal Systems • Typical model for volcano hosted geothermal system Volcano hosted Geothermal Systems-Menengai • Associated with main rift volcanoes Menengai Geothermal field • Temperatures of > 400oC measured • Shallow magma bodies ~2.3km Geophysical Model across Menengai • Seismics show high velocity under volcano • Common feature of all volcanoes in EARS rift axis MEQ Studies T o B MN15 a Marigat MN13 r in g Coffee o Farm MN12 Bahati ru Majani Mingi ru hu ya 9985000 N To MN14 • Studies revealed that 9980000 Kabarak s s s MN09 Bahati g g g brittle ductile transition MN10 n n n i i i CALDERA Settlement h h h t t t r r r o o o MN11 N N N MN07 To d d d i i i E r r r l MN08 do G G G re zone under Menengai is 9975000 t MN06 Residential Area MN04 at 6km depth T o Nairobi 9970000 NAKURU MN05 MN03URBAN AREA Lake Rongai Nakuru Lake Nakuru Farms National Park MN02 MN01 165000 170000 175000 180000 Grid Eastings (m) NorthWest Ol Rongai Men. Caldera SouthEast 0 -2 ) ) m m K K ( ( h h t t -4 p p e e D D -6 -8 165000 167500 170000 172500 175000 177500 180000 Distance (M) Menengai Stratigraphy • Stratigraphy dominated by trachytes and pyroclastics • Magma body at ~2.3km • Syenitic cap present • Tmax 400oC Menengai stratigraphic Model Tuff layers Trachyte Syenite Magma Menengai Model 200 isotherm 250 isotherm 350 isotherm Magma Olkaria Volcanic Complex • The heat source at Olkaria is associated with – discrete magma chambers that underlie the volcanic centres Main Ethiopian Rift Recent volcano tectonic activity is mainly within the axis. -

Analysis and Mapping of Water-Related Conflicts in the Catchment of Lake Naivasha (Kenya)

Competition over water resources: analysis and mapping of water-related conflicts in the catchment of Lake Naivasha (Kenya) Carolina Boix Fayos February 2002 Competition over water resources: analysis and mapping of water-related conflicts in the catchment of Lake Naivasha (Kenya) By Carolina Boix Fayos Supervisors: Dr. M.McCall (Social Sciences) Drs. J. Verplanke (Social Sciences) Drs. R. Becht (Water Resources) Thesis submitted to the International Institute for Geoinformation Science and Earth Observation in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Water Resources and Environmental Management Degree Assessment Board Chairman: Prof. Dr. A.M.J. Meijerink (Water Resources) External examiner: Prof. A. van der Veen (University of Twente) Members: Dr. M.K. McCall (Social Sciences) Drs. J.J. Verplanke (Social Sciences) Drs. R. Becht (Water Resources) INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR GEOINFORMATION SCIENCE AND EARTH OBSERVATION ENSCHEDE, THE NETHERLANDS Disclaimer This document describes work undertaken as part of a programme of study at the International Institute for Geoinformation Science and Earth Observation. All views and opinions expressed therein remain the sole responsibility of the author, and do not necessarily represent those of the institute. A mi abuelo Paco (Francisco Fayos Artés) que me enseñó a apreciar la tierra y sus gentes y a disfrutar con la Geografía y la Historia ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The experience of ITC has been very special. I am very grateful to the Fundación Alfonso Martín Escudero (Madrid, Spain) who paid the ITC fees and supported me economically during the whole period. I am also very grateful to my supervisors Dr. Mike McCall, Drs.