Arxiv:1609.06650V2 [Astro-Ph.SR] 26 Sep 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Richness of Compact Radio Sources in NGC 6334D to F S.-N

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. main c ESO 2021 June 22, 2021 The richness of compact radio sources in NGC 6334D to F S.-N. X. Medina1, S. A. Dzib1, M. Tapia2, L. F. Rodríguez3, and L. Loinard3;4 1 Max-Planck-Institut für Radioastronomie, Auf dem Hügel 69, D-53121 Bonn, Germany 2 Instituto de Astronomía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ensenada, B. C., CP 22830, Mexico 3 Instituto de Radioastronomía y Astrofísica, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Morelia 58089, Mexico 4 Instituto de Astronomía, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Apartado Postal 70-264, CdMx C.P. 04510, Mexico e-mail: smedina, sdzib, @mpifr-bonn.mpg.de; [email protected]; l.rodriguez, and l.loinard, @crya.unam.mx Received 2017; ABSTRACT Context. The presence and properties of compact radio sources embedded in massive star-forming regions can reveal important physical properties about these regions and the processes occurring within them. The NGC 6334 complex, a massive star-forming region, has been studied extensively. Nevertheless, none of these studies has focused in its content in compact radio sources. Aims. Our goal here is to report on a systematic census of the compact radio sources toward NGC 6334, and their characteristics. This will be used to try and define their very nature. Methods. We use VLA C band (4–8 GHz) archive data with 000.36 (500 AU) of spatial resolution and noise level of 50 µJy bm−1 to carry out a systematic search for compact radio sources within NGC 6334. We also search for infrared counterparts to provide some constraints on the nature of the detected radio sources. -

Rosette Nebula and Monoceros Loop

Oshkosh Scholar Page 43 Studying Complex Star-Forming Fields: Rosette Nebula and Monoceros Loop Chris Hathaway and Anthony Kuchera, co-authors Dr. Nadia Kaltcheva, Physics and Astronomy, faculty adviser Christopher Hathaway obtained a B.S. in physics in 2007 and is currently pursuing his masters in physics education at UW Oshkosh. He collaborated with Dr. Nadia Kaltcheva on his senior research project and presented their findings at theAmerican Astronomical Society meeting (2008), the Celebration of Scholarship at UW Oshkosh (2009), and the National Conference on Undergraduate Research in La Crosse, Wisconsin (2009). Anthony Kuchera graduated from UW Oshkosh in May 2008 with a B.S. in physics. He collaborated with Dr. Kaltcheva from fall 2006 through graduation. He presented his astronomy-related research at Posters in the Rotunda (2007 and 2008), the Wisconsin Space Conference (2007), the UW System Symposium for Undergraduate Research and Creative Activity (2007 and 2008), and the American Astronomical Society’s 211th meeting (2008). In December 2009 he earned an M.S. in physics from Florida State University where he is currently working toward a Ph.D. in experimental nuclear physics. Dr. Nadia Kaltcheva is a professor of physics and astronomy. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Sofia in Bulgaria. She joined the UW Oshkosh Physics and Astronomy Department in 2001. Her research interests are in the field of stellar photometry and its application to the study of Galactic star-forming fields and the spiral structure of the Milky Way. Abstract An investigation that presents a new analysis of the structure of the Northern Monoceros field was recently completed at the Department of Physics andAstronomy at UW Oshkosh. -

Spatial and Kinematic Structure of Monoceros Star-Forming Region

MNRAS 476, 3160–3168 (2018) doi:10.1093/mnras/sty447 Advance Access publication 2018 February 22 Spatial and kinematic structure of Monoceros star-forming region M. T. Costado1‹ and E. J. Alfaro2 1Departamento de Didactica,´ Universidad de Cadiz,´ E-11519 Puerto Real, Cadiz,´ Spain. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-abstract/476/3/3160/4898067 by Universidad de Granada - Biblioteca user on 13 April 2020 2Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa, CSIC, Apdo 3004, E-18080 Granada, Spain Accepted 2018 February 9. Received 2018 February 8; in original form 2017 December 14 ABSTRACT The principal aim of this work is to study the velocity field in the Monoceros star-forming region using the radial velocity data available in the literature, as well as astrometric data from the Gaia first release. This region is a large star-forming complex formed by two associations named Monoceros OB1 and OB2. We have collected radial velocity data for more than 400 stars in the area of 8 × 12 deg2 and distance for more than 200 objects. We apply a clustering analysis in the subspace of the phase space formed by angular coordinates and radial velocity or distance data using the Spectrum of Kinematic Grouping methodology. We found four and three spatial groupings in radial velocity and distance variables, respectively, corresponding to the Local arm, the central clusters forming the associations and the Perseus arm, respectively. Key words: techniques: radial velocities – astronomical data bases: miscellaneous – parallaxes – stars: formation – stars: kinematics and dynamics – open clusters and associations: general. Hoogerwerf & De Bruijne 1999;Lee&Chen2005; Lombardi, 1 INTRODUCTION Alves & Lada 2011). -

Winter Constellations

Winter Constellations *Orion *Canis Major *Monoceros *Canis Minor *Gemini *Auriga *Taurus *Eradinus *Lepus *Monoceros *Cancer *Lynx *Ursa Major *Ursa Minor *Draco *Camelopardalis *Cassiopeia *Cepheus *Andromeda *Perseus *Lacerta *Pegasus *Triangulum *Aries *Pisces *Cetus *Leo (rising) *Hydra (rising) *Canes Venatici (rising) Orion--Myth: Orion, the great hunter. In one myth, Orion boasted he would kill all the wild animals on the earth. But, the earth goddess Gaia, who was the protector of all animals, produced a gigantic scorpion, whose body was so heavily encased that Orion was unable to pierce through the armour, and was himself stung to death. His companion Artemis was greatly saddened and arranged for Orion to be immortalised among the stars. Scorpius, the scorpion, was placed on the opposite side of the sky so that Orion would never be hurt by it again. To this day, Orion is never seen in the sky at the same time as Scorpius. DSO’s ● ***M42 “Orion Nebula” (Neb) with Trapezium A stellar nursery where new stars are being born, perhaps a thousand stars. These are immense clouds of interstellar gas and dust collapse inward to form stars, mainly of ionized hydrogen which gives off the red glow so dominant, and also ionized greenish oxygen gas. The youngest stars may be less than 300,000 years old, even as young as 10,000 years old (compared to the Sun, 4.6 billion years old). 1300 ly. 1 ● *M43--(Neb) “De Marin’s Nebula” The star-forming “comma-shaped” region connected to the Orion Nebula. ● *M78--(Neb) Hard to see. A star-forming region connected to the Orion Nebula. -

How to Make $1000 with Your Telescope! – 4 Stargazers' Diary

Fort Worth Astronomical Society (Est. 1949) February 2010 : Astronomical League Member Club Calendar – 2 Opportunities & The Sky this Month – 3 How to Make $1000 with your Telescope! – 4 Astronaut Sally Ride to speak at UTA – 4 Aurgia the Charioteer – 5 Stargazers’ Diary – 6 Bode’s Galaxy by Steve Tuttle 1 February 2010 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 1 2 3 4 5 6 Algol at Minima Last Qtr Moon Æ 5:48 am 11:07 pm Top ten binocular deep-sky objects for February: M35, M41, M46, M47, M50, M93, NGC 2244, NGC 2264, NGC 2301, NGC 2360 Top ten deep-sky objects for February: M35, M41, M46, M47, M50, M93, NGC 2261, NGC 2362, NGC 2392, NGC 2403 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Algol at Minima Morning sports a Moon at Apogee New Moon Æ super thin crescent (252,612 miles) 8:51 am 7:56 pm Moon 8:00 pm 3RF Star Party Make use of the New Moon Weekend for . better viewing at the Dark Sky Site See Notes Below New Moon New Moon Weekend Weekend 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Presidents Day 3RF Star Party Valentine’s Day FWAS Traveler’s Guide Meeting to the Planets UTA’s Maverick Clyde Tombaugh Ranger 8 returns Normal Room premiers on Speakers Series discovered Pluto photographs and NatGeo 7pm Sally Ride “Fat Tuesday” Ash Wednesday 80 years ago. impacts Moon. 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 Algol at Minima First Qtr Moon Moon at Perigee Å (222,345 miles) 6:42 pm 12:52 am 4 pm {Low in the NW) Algol at Minima Æ 9:43 pm Challenge binary star for month: 15 Lyncis (Lynx) Challenge deep-sky object for month: IC 443 (Gemini) Notable carbon star for month: BL Orionis (Orion) 28 Notes: Full Moon Look for a very thin waning crescent moon perched just above and slightly right of tiny Mercury on the morning of 10:38 pm Feb. -

A Gaia DR2 View of the Open Cluster Population in the Milky Way T

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. manuscript˙arXiv2 © ESO 2018 July 13, 2018 A Gaia DR2 view of the Open Cluster population in the Milky Way T. Cantat-Gaudin1, C. Jordi1, A. Vallenari2, A. Bragaglia3, L. Balaguer-Nu´nez˜ 1, C. Soubiran4, D. Bossini2, A. Moitinho5, A. Castro-Ginard1, A. Krone-Martins5, L. Casamiquela4, R. Sordo2, and R. Carrera2 1 Institut de Ciencies` del Cosmos, Universitat de Barcelona (IEEC-UB), Mart´ı i Franques` 1, E-08028 Barcelona, Spain 2 INAF-Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, vicolo Osservatorio 5, 35122 Padova, Italy 3 INAF-Osservatorio di Astrofisica e Scienza dello Spazio, via Gobetti 93/3, 40129 Bologna, Italy 4 Laboratoire dAstrophysique de Bordeaux, Univ. Bordeaux, CNRS, UMR 5804, 33615 Pessac, France 5 CENTRA, Faculdade de Ciencias,ˆ Universidade de Lisboa, Ed. C8, Campo Grande, P-1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal Received date / Accepted date ABSTRACT Context. Open clusters are convenient probes of the structure and history of the Galactic disk. They are also fundamental to stellar evolution studies. The second Gaia data release contains precise astrometry at the sub-milliarcsecond level and homogeneous pho- tometry at the mmag level, that can be used to characterise a large number of clusters over the entire sky. Aims. In this study we aim to establish a list of members and derive mean parameters, in particular distances, for as many clusters as possible, making use of Gaia data alone. Methods. We compile a list of thousands of known or putative clusters from the literature. We then apply an unsupervised membership assignment code, UPMASK, to the Gaia DR2 data contained within the fields of those clusters. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Nebula in NGC 2264

Durham E-Theses The polarisation of the cone(IRN) Nebula in NGC 2264 Hill, Marianne C.M. How to cite: Hill, Marianne C.M. (1991) The polarisation of the cone(IRN) Nebula in NGC 2264, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6098/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk THE POLARISATION OF THE CONE(IRN) NEBULA IN NGC 2264 MARIANNE C. M. HILL A Thesis submitted to the University of Durham for the degree of Master of Science. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without prior consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. Department of Physics. September 1991 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. -

Astronomy Targets: September 2018 Unless Stated Otherwise, All Times Are for Mid-Month, for Birmingham UK and Are GMT+1

Astronomy targets: September 2018 Unless stated otherwise, all times are for mid-month, for Birmingham UK and are GMT+1. Rise & set times are for 20 degrees above horizon. Dark & light times are nautical twilight times (Sun 12 degrees below horizon) and astronomical darkness (Sun 18 degrees below horizon). © Andrew Butler, 2018. Sun and Moon data sourced from US Naval Observatory. Sun times Monday date Sunset Naut Astro Astro Naut Sunrise Moon Moon % Dark Dark Light Light 03/09/18 1951 2110 2158 0416 0504 0623 2353 → 40% 10/09/18 1935 2052 2137 0433 0518 0635 2% 17/09/18 1918 2033 2117 0448 0531 0647 ← 2346 60% 24/09/18 1902 2016 2057 0502 0544 0658 1916 → 100% Calendar 9 Sep New Moon 24 Sep Full Moon Planets Cygnus Sunset-0300, best 2210 Mars (low at Sunset) Emmission nebulae: Jupiter (low at Sunset) NGC6888 Crescent Nebula Saturn (low at Sunset) NGC6960 Veil Nebula Uranus (2230-Sunrise) IC5070 Pelican Nebula Neptune (2130-0330) IC7000 (C20) North American Nebula Planetary nebulae: Ursa Major Sunset-0150 IC5146 (C19) Cocoon Nebula Planetary nebula: M97 Owl Nebula NGC6826 Blinking Nebula Galaxies: NGC7008 Fetus Nebula M81 Bode’s Galaxy & M82 Cigar Galaxy Open clusters: M101 Pinwheel Galaxy M29 M108 M39 M109 NGC6871 Multiple star: Mizar & Alcor ζ-UMa (zeta-UMa) 3 white NGC6883 NGC6910 Rocking Horse Cluster Canes Venatici Sunset-2130 Galaxy: NGC6946 (C12) Fireworks Galaxy Globular cluster: M3 Multiple stars: Galaxies: Albireo β-Cyg (beta-Cyg) gold & blue M51 Whirlpool Galaxy 61-Cyg orange & red M63 Sunflower Galaxy M94 Delphinus Sunset-0240, -

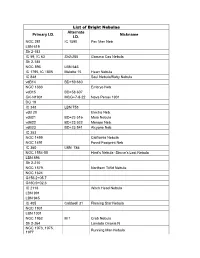

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

407 a Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , 351–353 Achromat

Index A Barnard 72 , 210–211 Abell Galaxy Cluster S 373 (AGC S 373) , Barnard, E.E. , 5, 389 351–353 Barnard’s loop , 5–8 Achromat , 365 Barred-ring spiral galaxy , 235 Adaptive optics (AO) , 377, 378 Barred spiral galaxy , 146, 263, 295, 345, 354 AGC S 373. See Abell Galaxy Cluster Bean Nebulae , 303–305 S 373 (AGC S 373) Bernes 145 , 132, 138, 139 Alnitak , 11 Bernes 157 , 224–226 Alpha Centauri , 129, 151 Beta Centauri , 134, 156 Angular diameter , 364 Beta Chamaeleontis , 269, 275 Antares , 129, 169, 195, 230 Beta Crucis , 137 Anteater Nebula , 184, 222–226 Beta Orionis , 18 Antennae galaxies , 114–115 Bias frames , 393, 398 Antlia , 104, 108, 116 Binning , 391, 392, 398, 404 Apochromat , 365 Black Arrow Cluster , 73, 93, 94 Apus , 240, 248 Blue Straggler Cluster , 169, 170 Aquarius , 339, 342 Bok, B. , 151 Ara , 163, 169, 181, 230 Bok Globules , 98, 216, 269 Arcminutes (arcmins) , 288, 383, 384 Box Nebula , 132, 147, 149 Arcseconds (arcsecs) , 364, 370, 371, 397 Bug Nebula , 184, 190, 192 Arditti, D. , 382 Butterfl y Cluster , 184, 204–205 Arp 245 , 105–106 Bypass (VSNR) , 34, 38, 42–44 AstroArt , 396, 406 Autoguider , 370, 371, 376, 377, 388, 389, 396 Autoguiding , 370, 376–378, 380, 388, 389 C Caldwell Catalogue , 241 Calibration frames , 392–394, 396, B 398–399 B 257 , 198 Camera cool down , 386–387 Barnard 33 , 11–14 Campbell, C.T. , 151 Barnard 47 , 195–197 Canes Venatici , 357 Barnard 51 , 195–197 Canis Major , 4, 17, 21 S. Chadwick and I. Cooper, Imaging the Southern Sky: An Amateur Astronomer’s Guide, 407 Patrick Moore’s Practical -

Atlas Menor Was Objects to Slowly Change Over Time

C h a r t Atlas Charts s O b by j Objects e c t Constellation s Objects by Number 64 Objects by Type 71 Objects by Name 76 Messier Objects 78 Caldwell Objects 81 Orion & Stars by Name 84 Lepus, circa , Brightest Stars 86 1720 , Closest Stars 87 Mythology 88 Bimonthly Sky Charts 92 Meteor Showers 105 Sun, Moon and Planets 106 Observing Considerations 113 Expanded Glossary 115 Th e 88 Constellations, plus 126 Chart Reference BACK PAGE Introduction he night sky was charted by western civilization a few thou - N 1,370 deep sky objects and 360 double stars (two stars—one sands years ago to bring order to the random splatter of stars, often orbits the other) plotted with observing information for T and in the hopes, as a piece of the puzzle, to help “understand” every object. the forces of nature. The stars and their constellations were imbued with N Inclusion of many “famous” celestial objects, even though the beliefs of those times, which have become mythology. they are beyond the reach of a 6 to 8-inch diameter telescope. The oldest known celestial atlas is in the book, Almagest , by N Expanded glossary to define and/or explain terms and Claudius Ptolemy, a Greco-Egyptian with Roman citizenship who lived concepts. in Alexandria from 90 to 160 AD. The Almagest is the earliest surviving astronomical treatise—a 600-page tome. The star charts are in tabular N Black stars on a white background, a preferred format for star form, by constellation, and the locations of the stars are described by charts.