Observations of Transiting Exoplanets with the JWST

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Exoplanet Populations with NASA's Kepler Mission

SPECIAL FEATURE: PERSPECTIVE PERSPECTIVE SPECIAL FEATURE: Exploring exoplanet populations with NASA’s Kepler Mission Natalie M. Batalha1 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, 94035 CA Edited by Adam S. Burrows, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and accepted by the Editorial Board June 3, 2014 (received for review January 15, 2014) The Kepler Mission is exploring the diversity of planets and planetary systems. Its legacy will be a catalog of discoveries sufficient for computing planet occurrence rates as a function of size, orbital period, star type, and insolation flux.The mission has made significant progress toward achieving that goal. Over 3,500 transiting exoplanets have been identified from the analysis of the first 3 y of data, 100 planets of which are in the habitable zone. The catalog has a high reliability rate (85–90% averaged over the period/radius plane), which is improving as follow-up observations continue. Dynamical (e.g., velocimetry and transit timing) and statistical methods have confirmed and characterized hundreds of planets over a large range of sizes and compositions for both single- and multiple-star systems. Population studies suggest that planets abound in our galaxy and that small planets are particularly frequent. Here, I report on the progress Kepler has made measuring the prevalence of exoplanets orbiting within one astronomical unit of their host stars in support of the National Aeronautics and Space Admin- istration’s long-term goal of finding habitable environments beyond the solar system. planet detection | transit photometry Searching for evidence of life beyond Earth is the Sun would produce an 84-ppm signal Translating Kepler’s discovery catalog into one of the primary goals of science agencies lasting ∼13 h. -

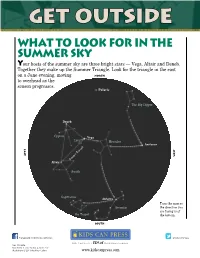

Get Outside What to Look for in the Summer Sky Your Hosts of the Summer Sky Are Three Bright Stars — Vega, Altair and Deneb

Get Outside What to Look for in the Summer Sky Your hosts of the summer sky are three bright stars — Vega, Altair and Deneb. Together they make up the Summer Triangle. Look for the triangle in the east on a June evening, moving NORTH to overhead as the season progresses. Polaris The Big Dipper Deneb Cygnus Vega Lyra Hercules Arcturus EaST West Summer Triangle Altair Aquila Sagittarius Antares Turn the map so Scorpius the direction you are facing is at the Teapot the bottom. south facebook.com/KidsCanBooks @KidsCanPress GET OUTSIDE Text © 2013 Jane Drake & Ann Love Illustrations © 2013 Heather Collins www.kidscanpress.com Get Outside Vega The Keystone The brightest star in the Between Vega and Arcturus, Summer Triangle, Vega is look for four stars in a wedge or The summer bluish white. It is in the keystone shape. This is the body solstice constellation Lyra, the Harp. of Hercules, the Strongman. His feet are to the north and Every day from late Altair his arms to the south, making December to June, the The second-brightest star in his figure kneel Sun rises and sets a little the triangle, Altair is white. upside down farther north along the Altair is in the constellation in the sky. horizon. But about June Aquila, the Eagle. 21, the Sun seems to stop Keystone moving north. It rises in Deneb the northeast and sets in The dimmest star of the the northwest, seemingly Summer Triangle, Deneb would in the same spots for be the brightest if it were not so Hercules several days. -

Predicting Exoplanet Observability in Time, Contrast, Separation, and Polarization, in Scattered Light

A&A 578, A59 (2015) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201424202 & c ESO 2015 Astrophysics Predicting exoplanet observability in time, contrast, separation, and polarization, in scattered light Guillaume Schworer1;2 and Peter G. Tuthill2 1 LESIA, Observatoire de Paris, CNRS/UMR 8109, UPMC, Université Paris Diderot, 5 place J. Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Sydney Institute for Astronomy (SIfA), School of Physics, The University of Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Received 14 May 2014 / Accepted 14 March 2015 ABSTRACT Context. Polarimetry is one of the keys to enhanced direct imaging of exoplanets. Not only does it deliver a differential observable pro- viding extra contrast, but when coupled with spectroscopy, it also reveals valuable information on the exoplanetary atmospheric com- position. Nevertheless, angular separation and contrast ratio to the host-star make for extremely challenging observation. Producing detailed predictions for exactly how the expected signals should appear is of critical importance for the designs and observational strategies of tomorrow’s telescopes. Aims. We aim at accurately determining the magnitudes and evolution of the main observational signatures for imaging an exoplanet: separation, contrast ratio to the host-star and polarization as a function of the orbital geometry and the reflectance parameters of the exoplanet. Methods. These parameters were used to construct a polarized-reflectance model based on the input of orbital parameters and two albedo values. The model is able to calculate a variety of observational predictions for exoplanets at any orbital time. Results. The inter-dependency of the three main observational criteria – angular separation, contrast ratio, polarization – result in a complex time-evolution of the system. -

Photospheric Activity, Rotation and Magnetic Interaction in LHS 6343 A

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. lhs6343_v9 c ESO 2018 May 4, 2018 Photospheric activity, rotation and magnetic interaction in LHS 6343 A E. Herrero1, A. F. Lanza2, I. Ribas1, C. Jordi3, and J. C. Morales1, 3 1 Institut de Ciències de l’Espai (CSIC-IEEC), Campus UAB, Facultat de Ciències, Torre C5 parell, 2a pl, 08193 Bellaterra, Spain, e-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 2 INAF - Osservatorio Astrofisico di Catania, via S. Sofia, 78, 95123 Catania, Italy, e-mail: [email protected] 3 Dept. d’Astronomia i Meteorologia, Institut de Ciències del Cosmos (ICC), Universitat de Barcelona (IEEC-UB), Martí Franquès 1, E08028 Barcelona, Spain, e-mail: [email protected] Received <date> / Accepted <date> ABSTRACT Context. The Kepler mission has recently discovered a brown dwarf companion transiting one member of the M4V+M5V visual binary system LHS 6343 AB with an orbital period of 12.71 days. Aims. The particular interest of this transiting system lies in the synchronicity between the transits of the brown dwarf C component and the main modulation observed in the light curve, which is assumed to be caused by rotating starspots on the A component. We model the activity of this star by deriving maps of the active regions that allow us to study stellar rotation and the possible interaction with the brown dwarf companion. Methods. An average transit profile was derived, and the photometric perturbations due to spots occulted during transits are removed to derive more precise transit parameters. We applied a maximum entropy spot model to fit the out-of-transit optical modulation as observed by Kepler during an uninterrupted interval of 500 days. -

University of California Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ BENEATH THE SURFACE OF GIANT PLANETS: EVOLUTION, STRUCTURE, AND COMPOSITION A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS by Neil L Kelly Miller March 2013 The Dissertation of Neil L Kelly Miller is approved: Jonathan Fortney, Chair Professor D. Lin Professor P. Garaud Professor P. Bodenheimer Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Neil L Kelly Miller 2013 Table of Contents List of Figures v List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Dedication xv Acknowledgments xvi 1 Introduction 1 1.1 TheSolarSystemGiantPlanets . 3 1.2 FromIndividualSystemstoSamples . 4 1.3 Physical Processes in the Evolution of Giant Planets . ........ 8 2 Coupled Thermal and Tidal Evolution of Giant Expolanets 14 2.1 Abstract.................................... 14 2.2 Introduction.................................. 15 2.3 Model:Introduction ............................. 21 2.4 Model:Implementation ........................... 23 2.5 GeneralExamples .............................. 29 2.6 Results..................................... 37 2.6.1 SpecificSystems ........................... 37 2.6.2 SummaryforSuite .......................... 47 ′ 2.6.3 High Qs cases............................. 56 2.7 Discussion&Conclusions . 59 3 Applications of Giant Planet Thermal Evolution Model 74 3.1 Introduction.................................. 74 3.2 CoRoT-2b: Young Planet With Potentially Tidally Inflated Radius . 75 3.3 CoRoT-7b: Potential Evaporative Mass Loss Scenario . ....... 78 3.3.1 EvaporativeMassLossModel. 80 iii 3.3.2 PlanetEvolution ........................... 82 3.4 Kepler11 ................................... 82 3.4.1 Formation and Compositions of Kepler 11 Planets . 82 4 Measuring the Heavy Element Composition of Giant Exoplanets with Lower Irradiation 86 4.1 Abstract.................................... 86 4.2 Introduction.................................. 87 4.3 ModelandMethod............................. -

Summer Constellations

Night Sky 101: Summer Constellations The Summer Triangle Photo Credit: Smoky Mountain Astronomical Society The Summer Triangle is made up of three bright stars—Altair, in the constellation Aquila (the eagle), Deneb in Cygnus (the swan), and Vega Lyra (the lyre, or harp). Also called “The Northern Cross” or “The Backbone of the Milky Way,” Cygnus is a horizontal cross of five bright stars. In very dark skies, Cygnus helps viewers find the Milky Way. Albireo, the last star in Cygnus’s tail, is actually made up of two stars (a binary star). The separate stars can be seen with a 30 power telescope. The Ring Nebula, part of the constellation Lyra, can also be seen with this magnification. In Japanese mythology, Vega, the celestial princess and goddess, fell in love Altair. Her father did not approve of Altair, since he was a mortal. They were forbidden from seeing each other. The two lovers were placed in the sky, where they were separated by the Celestial River, repre- sented by the Milky Way. According to the legend, once a year, a bridge of magpies form, rep- resented by Cygnus, to reunite the lovers. Photo credit: Unknown Scorpius Also called Scorpio, Scorpius is one of the 12 Zodiac constellations, which are used in reading horoscopes. Scorpius represents those born during October 23 to November 21. Scorpio is easy to spot in the summer sky. It is made up of a long string bright stars, which are visible in most lights, especially Antares, because of its distinctly red color. Antares is about 850 times bigger than our sun and is a red giant. -

Lhs 6343 C: a Transiting Field Brown Dwarf Discovered by the Kepler Mission∗

The Astrophysical Journal, 730:79 (11pp), 2011 April 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/730/2/79 C 2011. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. LHS 6343 C: A TRANSITING FIELD BROWN DWARF DISCOVERED BY THE KEPLER MISSION∗ John Asher Johnson1,2, Kevin Apps3, J. Zachary Gazak4, Justin R. Crepp1, Ian J. Crossfield5, Andrew W. Howard6, Geoff W. Marcy6, Timothy D. Morton1, Carly Chubak6, and Howard Isaacson6 1 Department of Astrophysics, California Institute of Technology, MC 249-17, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA; [email protected] 2 NASA Exoplanet Science Institute (NExScI), CIT Mail Code 100-22, 770 South Wilson Avenue, Pasadena, CA 91125, USA 3 Cheyne Walk Observatory, 75B Cheyne Walk, Horley, Surrey, RH6 7LR, UK 4 Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai’i, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 5 Department of Physics and Astronomy, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA 6 Department of Astronomy, University of California, Mail Code 3411, Berkeley, CA 94720, USA Received 2010 September 8; accepted 2011 January 18; published 2011 March 8 ABSTRACT We report the discovery of a brown dwarf that transits one member of the M+M binary system LHS 6343 AB every 12.71 days. The transits were discovered using photometric data from the Kepler public data release. The LHS 6343 stellar system was previously identified as a single high proper motion M dwarf. We use adaptive optics imaging to resolve the system into two low-mass stars with masses 0.370 ± 0.009 M and 0.30 ± 0.01 M, respectively, and a projected separation of 0.55. -

September 2016

11/20/2016 11:13 AM CHECK RECONCILIATION REGISTER PAGE: 1 COMPANY: 04 - COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT CHECK DATE: 9/01/2016 THRU 9/30/2016 ACCOUNT: 10010 CASH C.D.B.G. - CHECKING CLEAR DATE: 0/00/0000 THRU 99/99/9999 TYPE: Check STATEMENT: 0/00/0000 THRU 99/99/9999 STATUS: All VOIDED DATE: 0/00/0000 THRU 99/99/9999 FOLIO: All AMOUNT: 0.00 THRU 999,999,999.99 CHECK NUMBER: 000000 THRU 999999 ACCOUNT --DATE-- --TYPE-- NUMBER ---------DESCRIPTION---------- ----AMOUNT--- STATUS FOLIO CLEAR DATE CHECK: ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 10010 9/08/2016 CHECK 006680 LOWER RIO GRANDE VALLEY 1,702.00CR CLEARED A 10/10/2016 10010 9/08/2016 CHECK 006681 MISSION CRIME STOPPERS 2,726.60CR CLEARED A 10/10/2016 10010 9/22/2016 CHECK 006682 A ONE INSULATION 5,950.00CR CLEARED A 10/10/2016 10010 9/22/2016 CHECK 006683 A ONE INSULATION 5,950.00CR CLEARED A 10/10/2016 10010 9/22/2016 CHECK 006684 A ONE INSULATION 5,850.00CR CLEARED A 10/10/2016 10010 9/22/2016 CHECK 006685 A ONE INSULATION 5,850.00CR CLEARED A 10/10/2016 10010 9/22/2016 CHECK 006686 CHILDREN'S ADV.CENTER HDL 911.62CR CLEARED A 10/10/2016 10010 9/22/2016 CHECK 006687 G&G CONTRACTORS 23,920.00CR CLEARED A 10/10/2016 10010 9/29/2016 CHECK 006688 AMIGOS DEL VALLE 1,631.05CR CLEARED A 11/07/2016 10010 9/29/2016 CHECK 006689 DELL MARKETING L.P. 1,148.00CR CLEARED A 11/07/2016 10010 9/29/2016 CHECK 006690 LOWER RIO GRANDE VALLEY 2,682.54CR CLEARED A 11/07/2016 10010 9/29/2016 CHECK 006691 SILVER RIBBON COMMUNITY PARTNE 815.04CR -

Transit Timing Analysis of the Hot Jupiters WASP-43B and WASP-46B and the Super Earth Gj1214b

Transit timing analysis of the hot Jupiters WASP-43b and WASP-46b and the super Earth GJ1214b Mathias Polfliet Promotors: Michaël Gillon, Maarten Baes 1 Abstract Transit timing analysis is proving to be a promising method to detect new planetary partners in systems which already have known transiting planets, particularly in the orbital resonances of the system. In these resonances we might be able to detect Earth-mass objects well below the current detection and even theoretical (due to stellar variability) thresholds of the radial velocity method. We present four new transits for WASP-46b, four new transits for WASP-43b and eight new transits for GJ1214b observed with the robotic telescope TRAPPIST located at ESO La Silla Observatory, Chile. Modelling the data was done using several Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations of the new transits with old data and a collection of transit timings for GJ1214b from published papers. For the hot Jupiters this lead to a general increase in accuracy for the physical parameters of the system (for the mass and period we found: 2.034±0.052 MJup and 0.81347460±0.00000048 days and 2.03±0.13 MJup and 1.4303723±0.0000011 days for WASP-43b and WASP-46b respectively). For GJ1214b this was not the case given the limited photometric precision of TRAPPIST. The additional timings however allowed us to constrain the period to 1.580404695±0.000000084 days and the RMS of the TTVs to 16 seconds. We investigated given systems for Transit Timing Variations (TTVs) and variations in the other transit parameters and found no significant (3sv) deviations. -

A Large Hα Line Forming Region for the Massive Interacting Binaries Β

A&A 532, A148 (2011) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/201116742 & c ESO 2011 Astrophysics AlargeHα line forming region for the massive interacting binaries β Lyrae and υ Sagitarii D. Bonneau1, O. Chesneau1, D. Mourard1, Ph. Bério1,J.M.Clausse1, O. Delaa1,A.Marcotto1, K. Perraut2, A. Roussel1,A.Spang1,Ph.Stee1, I. Tallon-Bosc3, H. McAlister4,5, T. ten Brummelaar5, J. Sturmann5, L. Sturmann5, N. Turner5, C. Farrington5, and P. J. Goldfinger5 1 Lab. H. Fizeau, Univ. Nice Sophia Antipolis, CNRS UMR 6525, Obs. de la Côte d’Azur, Av. Copernic, 06130 Grasse, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 UJF-Grenoble 1/CNRS-INSU, Inst. de Planétologie et d’Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG) UMR 5274, Grenoble 38041, France 3 Univ. Lyon 1, Observatoire de Lyon, 9 avenue Charles André, Saint-Genis Laval 69230, France 4 Georgia State University, PO Box 3969, Atlanta GA 30302-3969, USA 5 CHARA Array, Mount Wilson Observatory, 91023 Mount Wilson CA, USA Received 17 February 2011 / Accepted 1 July 2011 ABSTRACT Aims. This study aims at constraining the properties of two interacting binary systems by measuring their continuum-forming region in the visible and the forming regions of some emission lines, in particular Hα, using optical interferometry. Methods. We have obtained visible medium (R ∼ 1000) spectral resolution interferometric observations of β Lyr and of υ Sgr using the VEGA instrument of the CHARA array. For both systems, visible continuum (520/640 nm) visibilities were estimated and differential interferometry data were obtained in the Hα emission line at several epochs of their orbital period. -

![Arxiv:2003.04650V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 10 Mar 2020 Sphere (Arcangeli Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7992/arxiv-2003-04650v1-astro-ph-ep-10-mar-2020-sphere-arcangeli-et-al-217992.webp)

Arxiv:2003.04650V1 [Astro-Ph.EP] 10 Mar 2020 Sphere (Arcangeli Et Al

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. main c ESO 2020 March 11, 2020 Detection of Fe i and Fe ii in the atmosphere of MASCARA-2b using a cross-correlation method M. Stangret1,2, N. Casasayas-Barris1,2, E. Pallé1,2, F. Yan3, A. Sánchez-López4, M. López-Puertas4 1 Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias, Vía Láctea s/n, 38205 La Laguna, Tenerife, Spain e-mail: [email protected] 2 Departamento de Astrofísica, Universidad de La Laguna, 38200 San Cristobal de La Laguna, Spain 3 Institut für Astrophysik, Georg-August-Universität, Friedrich-Hund-Platz 1, 37077 Göttingen, Germany 4 Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía (IAA-CSIC), Glorieta de la Astronomía s/n, 18008 Granada, Spain Received 21 January 2020; accepted 27 February 2020 ABSTRACT Ultra-hot Jupiters are gas giants planets whose dayside temperature, due to the strong irradiation received from the host star, is greater than 2200 K. These kind of objects are perfect laboratories to study chemistry of exoplanetary upper atmospheres via trans- mission spectroscopy. Exo-atmospheric absorption features are buried in the noise of the in-transit residual spectra. However we can retrieve the information of hundreds of atmospheric absorption lines by performing a cross-correlation with an atmospheric transmission model, which allows us to greatly increase the exo-atmospheric signal. At the high-spectral resolution of our data, the Rossiter-McLaughlin effect and centre-to-limb variation have a strong contribution. Here, we present the first detection of Fe i and the confirmation of absorption features of Fe ii in the atmosphere of the ultra-hot Jupiter MASCARA-2b/KELT-20b, by using three transit observations with HARPS-N. -

News from the High Plains

Department of Physics & Astronomy Greetings Alumni & Friends, February 2014 Physics & Astronomy at 7200’ is alive and kicking. The enclosed plot shows how News from the our student population has seen significant growth over the past decade to a present total of 115, including 38 graduate students (see also the Sputnik-era spike!). This High Plains growth has gone hand-in-hand with the University’s decision to recommit to physics. Our astronomy program now has expertise in star formation, planetary formation, galaxies, quasars, instrumentation, and cosmology. UW physicists work on a wide array of areas in condensed matter physics and biophysics. Much of the focus has been on developing and understanding nanostructures geared toward efficient energy transportation and conversion (e.g., solar cells). Our physics faculty have also been working with the departments of Chemistry, Chemical & Petroleum Engineering, and Mechanical Engineering to develop a cross-college, interdisciplinary Materials Science and Engineering program. This program allows students to take courses from multiple departments, carry out collaborative research, and ultimately pursue a terminal degree in their home departments with a concentration in Materials Science. In terms of infrastructure, our program is almost unrecognizable from where it stood just a few years ago. We now have a first-class nano-fabrication and characterization lab that includes key pieces of equipment such as an electron-beam evaporator, X-ray diffractometer, reactive ion etcher, chemical vapor deposition systems, mask aligner, etc. Our newest faculty member, TeYu Chien, is building up a lab centered around Spring Graduates a state-of-the-art scanning tunneling microscope. Our observatory WIRO is also continuing to see upgrades.