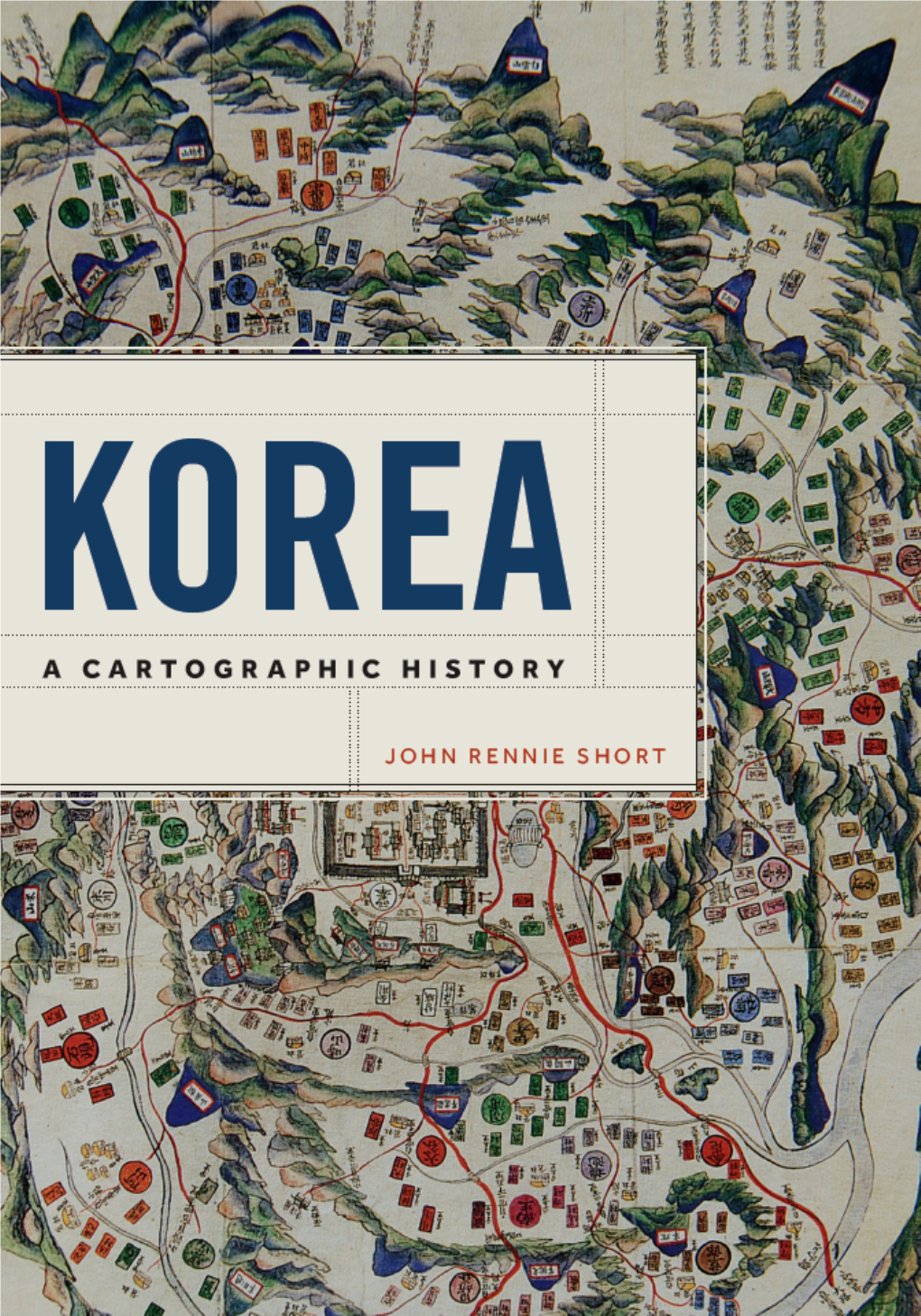

Korea in the Modern Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping the Oriental Sky

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University Mapping the Oriental Sky Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Oriental Astronomy (ICOA-7) Edited by Tsuko NAKAMURA, Wayne ORCHISTON, Mitsuru SOMA & Richard STROM Held on September 6-10, 2010 National Astronomical Observatory of Japan Mitaka, Tokyo I ..: � a Q) rJ) co - Mapping the Oriental Sky Proceedings of the Seventh International Conference on Oriental Astronomy (ICOA-7) Edited by Tsuko NAKAMURA, Wayne ORCHISTON, Mitsuru SOMA, & Richard STROM Held on September 6 -1 0, 2010 National Astronomical Observatory of Japan Mitaka, Tokyo Printed in Tokyo, 2011 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Preface 7 Conference Participants 8 Conference Program 9 A Selection of Photographs from the Conference 11 Part I. Archaeoastronomy and ethnoastronomy "Megaliths in Ancient India and Their Possible Association with Astronomy" Mayank N. VAHIA, Srikumar M. MENON, Riza ABBAS, and Nisha YADAV 13 "Megalithic Astronomy in South IndiaH Srikumar M. MENON and Mayank N. VAHIA 21 "Theoretical Framework of Harappan Astronomy" Mayank N. VAHIA and Srikumar M. MENON 27 "Orientation of Borobudur's East Gate Measured against the Sunrise Position during the Vernal Equinox" Irma I. HARIAWANG, Ferry M. SIMATUPANG, Iratius RADIMAN, and Emanuel S. MUMPUNI 37 "The Sky and the Agro-Bio-Climatology of Java. 15 There a Need for a Critical Reevaluation due to Environmental Changes?" Bambang HIDAYAT 43 "Prospects for Scholarship in Archaeoastronomy and Cultural Astronomy in Japan: Interdisciplinary Perspectivesn Steven L. RENSHAW 47 "The Big Dipper, Sword, Snake and Turtle: Four Constellations as Indicators of the Ecliptic Pole in Ancient China?" Stefan MAEDER 57 PartII. -

Unit 1: University and Me

English II UNIT 1: UNIVERSITY AND ME Class 1 Introduce yourself and others Be - Personal pronouns / adj. Talk about university Present simple, frequency, like Descriptions There is/are – a/ some - lot of Ask and answer about routines Class 2 and 3 The best university? Routines Describing and comparing universities Descriptions Comparatives and superlatives Class 4 Classroom language Focus on speaking revising previous Situations at university: classes Getting to know a new student 1 group makes the summary of this unit The perfect classroom The crazy classroom Class 5 Revision Summary Assignment: Advertise your university (poster? Audio spot? Audiovisual spot?) INTRODUCE YOURSELF AND OTHERS 1.What do you know about your classmates? Write sentences using these prompts: His/her name is (S)he loves (S)he likes (S)he hates (S)he usually (S)he sometimes (S)he never Last semester s(he) (S)he doesn’t like (S)he can (S)he has 2.Introduce yourself 3.What do you remember about your classmates’ introductions? 1 English II TALK ABOUT UNIVERSITY 2 English II 1 1 Taken from: New Language Leader Elementary (p.16-17) 3 English II THE BEST UNIVERSITY? Reading: what university do you prefer? Why? AL-FARABI KAZAKH NATIONAL UNIVERSITY (KAZNU) The country’s oldest and largest university is situated in the former capital city, Almaty. Al-Farabi Kazakh National University (KazNU) was established in 1934 and currently teaches more than 20,000 students, both undergraduates and postgraduates. The university’s “Kazgugrad” campus is the largest in the country, covering a total area of 100 hectares, and holding all of the 14 faculties and 98 departments. -

Study Abroad at Yonsei University in South Korea

Study abroad at Yonsei University in South Korea I am very thankful to have attended Yonsei University located in Seoul in South Korea during the fall semester in 2014 (August 2014-December 2014). It is a sky university of South Korea and thus belongs to the best universities of Asia. However, I believe that the focus of a study abroad semester should not lie on the academic side, but on getting to know other nationalities and in particular the host country with its culture, customs, sights and people. Thus, after my arrival in Seoul, I started to plan trips across Korea with other exchange students and to neighbouring countries such as Japan, China and Hong Kong. Preparation However, before leaving to South Korea you have to arrange some things: Firstly, do make sure that you apply and pay on time for student housing if you want to live on campus. I applied to the International House and was sharing my room and was very happy with my choice, as you are immediately in a social environment. Secondly, you need to apply for a visa. Yonsei University will send you a proof of enrolment, which you need to bring. Ask at the embassy for a multiple entry visa if you want to travel during your exchange. Moreover, Yonsei requires a TB test for student housing, so plan this well in advance. Arrival Arriving at the airport you need to change money or withdrawal money as you need Korean Won either for taking a taxi, bus or metro. I would recommend taking the limousine bus if you have a lot of luggage. -

“University-Based Meritocracy" and Duality of Higher Education Effect"

HIGHER EDUCATION AND SOCIAL MOBILITY IN KOREA “University-Based Meritocracy" and Duality of Higher Education Effect" Youngdal Cho and Hiwon Yoon Seoul National University Salzburg Global Seminar Salzburg, Austria 2-7 October 2012 “University-Based Meritocracy" and Duality of Higher Education Effect Page 1 Abstract Rapid industrialization and democratization of Korea has become a center increasing interest of the world and it is told that „education‟ or Koreans‟ attitude toward education made “The miracle of the Han River. In the process of industrialization of Korea, it is generally admitted that higher education played a decisive role. The present paper tries to answer the question about the role of universities in the process of social mobility in Korea. Traditionally (and even up to these days), Korean people has an absolute trust in „good‟ education and are convinced that admission to a prestigious university would and should guarantee a bright future. That is to say, Koreans are still keeping their “faith” in universities for their function of an agency of meritocracy. It was, basically, Confucianism that has been embedded as a foundation of those beliefs, values, and traditions in the educational system of Korea. Confucian philosophy highly esteemed value of pursuit of learning not only as an objective in itself, but also as a vehicle to self-betterment. Actually, in Korean society, education has been and IS the major means for young people to raise their social status, regardless of their own family background. Nevertheless, in reality, higher education in Korea is two faced in its function. The one is to enable social mobility on the basis of traditional meritocracy and the other is to intensify educational inequality and consolidate social classes because of intense competition (which means, very often, very high cost of preparation) to get an admission from prestigious universities that only socio-economically well established class can afford. -

Yonsei University Seoul, South Korea 79381W

Exchange Report - Spring 2015 Yonsei University Seoul, South Korea 79381W Source: http://www.uq.edu.au/uqabroad/yonsei-university Yonsei University 50 Yonsei-ro Sepdaemun-gu Seoul SOUTH KOREA Preparing for the exchange Having lived in the United States and Australia, Asia felt like a good destination for my exchange year. The final choice was between Hong Kong, Japan and South Korea. Hong Kong did not offer any Master level exchange and Japan being very expensive I decided to with South Korea. I had also met many Koreans during my earlier travels, who had been really nice and fun people, which also mattered in the choice. All of the three universities that Aalto has an exchange deal with are located in the capital, Seoul. All three SKY-universities (Seoul National University, Korea University and Yonsei University) are top universities in Korea, and people are proud to be alumni or current students of each one of them. The choice between these three universities was in the end fairly easy. I heard from several sources that Yonsei University has a really vibe and there is a lot going on around the university. This was a very important factor in my decision, since I knew that all three universities are very respected in academics. I also saw the exchange semester of 50% of studying and 50% getting to know the country, culture and meeting new people. After being selected to Yonsei University in the internal selection of Aalto I had to still do an online application on Yonsei University’s web site. This required some basic information such as name, home university, major etc. -

Glossary Tested

GREAT DECISIONS 1918 • FOREIGN POLICY ASSOCIATION 2016 EDITION 5. Korean Choices Acronyms and abbreviations Creative Economy: An initiative by Park Geun hye’s government that champions small-to-medium sized MERS—Middle East respiratory syndrome businesses and start-ups as the future drivers of national NGO—Non-governmental organization economic growth. The plan is a turn away from the post- OECD—Organization for Economic Co-operation and war model, which was focused on large conglomerates Development (chaebols). SKY universities—The most prestigious South Korean universities, consisting of Seoul National University, Dokdo/Takeshima Island dispute: A longstanding dis- Korea University, Yonsei University pute between Korea and Japan over an island group SOFA—Status of Forces Agreement known as Dokdo or Takeshema, respectively. The is- UN—United Nations lands were annexed by Japan in 1905 and restored to South Korea after WWII, but sovereignty remains con- Glossary tested. 386 Generation: The generation of South Koreans born Economic Democratization: A main platform of Park in the 1960s who were politically active during the dem- Geun hye’s presidential election campaign, which prom- ocratic transition of the 1980s. ised to decrease chaebol infuence and expand the wel- fare state. Asian Games: A pan-continental multi-sport competi- tion organized every four years by the Olympic Council Eurasia Initiative: President Park Geun hye’s 2013 of Asia. proposal for a system of unifed transport, trade and energy across Eurasia. It would connect rail, road and Asia’s Paradox: The term coined by President Park sea routes, from London to Seoul, through Russia and Geun-hye to refer to the antithetical situation of regional North Korea. -

Freeman Scholars Asia Abroad Program

Matthew Wilmot The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Wendy Tong Barnes Scholarship Fall 2016 Introduction To me I have always studied abroad. I grew up in Australia and moved to Hawaii to attend college at UH Manoa. Moving to Hawaii was definitely a new environment and required me to get used to living and studying in a new country and creating a new circle of friends. What I learnt from this experience is that I grew up as a person, became more confident, and was able to take on heavier loads of work. When I found out about the opportunity to study abroad through Shidler I was excited to attempt moving again to another country, challenging myself to go through the experience again. I decided to study in Asia but wasn’t sure which school. I looked into the SKY universities (i.e., Seoul National University, Korea University, Yonsei University) in Korea and some schools in Japan and completely overlooked Hong Kong. Rikki Mitsunaga later mentioned to me the possibility of studying at the University of Hong Kong and that opportunity alone was all I needed. The University of Hong Kong is one of the top universities in Asia and has a tough international business management program, so I was really excited to challenge myself academically. I was expecting the students there to be much more educated and self- disciplined and I was expecting the workload to be a lot higher than here in Hawaii. I was expecting Hong Kong to be a big city. I had never really lived in a city and was nervous about missing out on things I’m passionate about such as surfing, hiking, and anything in the water. -

Students and Parents' Bulletin 8

No. 8 A.Y. 2020-2021 October 16, 2020 STUDENTS AND PARENTS' B U L L E T I N Internationally Accredited by the Western Association of Schools and Colleges; Recognized by the Department of Education as a School of the Future; An International Baccalaureate (I.B.) Authorized World School; Investors in People Gold Awardee; ISO 9001:2008 Certified Math whiz hauls gold medals from 3 int’l math competitions Ervin Joshua Bautista A Southville International School and Colleges (SISC) high school student brought home 3 gold medals from various international math competitions done online. Joshua Bautista of Gr. 8 - Integrity triumphed at the International Kangaroo Mathematics Competition (IKMC) based in Paris, the Mathematics Without Borders (MWB) tournament hosted by Bulgaria, and the Singapore and Asian School Math Olympiad (SASMO). Bautista received his awards for being one of the top scoring students at his level from hundreds of contestants representing 80 countries in IKMC, 19 countries in MWB, and 32 countries in SASMO. The contests moved online this year in response to the pandemic while continuing to showcase the mathematical talents of the participants. Alumna graduates with highest honors from one of SKY Universities Minkyoung Kyeong of the High School Class of 2015 recently graduated summa cum laude from one of South Korea’s prestigious SKY Universities and Asia’s top- performing schools - Yonsei University. (The SKY abbreviation refers to the first letters of the names of South Korea's most respected universities which are Seoul National University, Korea University, and Yonsei University.) It was a dream come true for Minkyoung who started from humble beginnings at SISC. -

SANGBIN IM B. 1976 Seoul, Korea Lives and Works in New York, US and Seoul, Korea

SANGBIN IM b. 1976 Seoul, Korea Lives and works in New York, US and Seoul, Korea Education 2011 Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY, Doctor of Education, Art and Art Education 2005 Yale University School of Art, New Haven, CT (Fulbright Award for Graduate Study in the United States), M.F.A. 2001 College of Fine Arts, Seoul National University, Seoul, KR Yewon School, Seoul Art High School, Seoul, KR Solo Exhibitions 2019 Sangbin IM: AI/IM, RYAN LEE, New York, NY Artificiality, Soul Art Space, Busan, KR 2017 Energia, Soul Art Space, Busan, KR 2016 Collection, RYAN LEE, New York, NY, US 2015 Mapping, Soul Art Space, Busan, Korea 2014 Simultaneous Echoes, Museo Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat, Buenos Aires, AR Antartica, Soul Art Space, Busan, KR 2013 Spectacle, RYAN LEE, New York, NY, US 2012 In the City, Soul Art Space, Busan, KR 2010 Sangbin IM: Confluence, Mary Ryan Gallery, New York, NY, US Sangbin IM: Encounter, PKM Trinity Gallery, Seoul, KR 2008 Sangbin IM: Recent Works, Gallery Sun Contemporary, Seoul, KR Sangbin IM: Recent Work, L2kontemporary Gallery, Los Angeles, CA, US Walter Randel Gallery, Recent Works, New York, NY, US 2007 Miki Wick Kim Contemporary Art, Zürich, CH Dreamscape, Janet Oh Gallery, Seoul, KR 2006 Sangbin IM Photographs, Cristinerose Gallery, New York, NY, US Sangbin IM & NEWSCAPE, Gana Art Center, Seoul, KR 2005 Body I City I History, ZONE Chelsea Center for the Arts, New York, NY, US 2001 Analogital, Gallery People, Seoul, KR Selected Group Exhibitions 2020 Mapping Korean Modern and Contemporary Art, -

UK-US Higher Education Partnerships: Firm Foundations and Promising

CIGE Insights U.K.-U.S. Higher Education Partnerships: Firm Foundations and Promising Pathways American Council on Education® YEARS Celebrating the Next Century of Leadership and Advocacy ACE and the American Council on Education are registered marks of the American Council on Education and may not be used or reproduced without the express written permission of ACE. American Council on Education One Dupont Circle NW Washington, DC 20036 © 2017. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, with- out permission in writing from the publisher. CIGE Insights U.K.-U.S. Higher Education Partnerships: Firm Foundations and Promising Pathways Robin Matross Helms Director Center for Internationalization and Global Engagement American Council on Education Lucia Brajkovic Senior Research Specialist Center for Internationalization and Global Engagement American Council on Education Jermain Griffin Research Associate Center for Internationalization and Global Engagement American Council on Education Support for the production and dissemination of this report provided by Sannam S4. CIGE Insights This series of occasional papers explores key issues and themes surrounding the inter- nationalization and global engagement of higher education. Papers include analysis, expert commentary, case examples, and recommendations for policy and practice. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of a number of organizations and individuals to this report. Sannam S4 provided funding for the project, as well as insights throughout the data gathering, writing, and editing process; Adrian Mutton, Zoe Marlow, Lakshmi Iyer, and Krista Northup made important contri- butions. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Through the Eyes of A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Through the Eyes of a Painter: Re-visioning Eighteenth-century Traditional Korean Paintings by Jeong Seon in Virtual Environments A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Media Arts and Technology by Intae Hwang Committee in charge: Professor Marko Peljhan, Co-Chair Professor Alenda Chang, Co-Chair Professor George Legrady June 2019 The dissertation of Intae Hwang is approved. _____________________________________________ George Legrady _____________________________________________ Marko Peljhan, Committee Co-Chair _____________________________________________ Alenda Chang, Committee Co-Chair June 2019 Through the Eyes of a Painter: Re-visioning Eighteenth-century Traditional Korean Paintings by Jeong Seon in Virtual Environments Copyright © 2019 by Intae Hwang iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am grateful to my academic committees. Professor George Legrady guided me on this topic. Professor Marko Peljhan was always supporting and encouraging this research during my five years of academic life with his generosity. Lots of discussion and revision with Professor Alenda Chang strengthened and broadened this research. I was happy to work with Professor Laila Sakr in the Wireframe Lab. With a special mention to my mentors in Chicago, Professor Jin Soo Kim gave me the courage to attend this program. I learned all the fundamental methodologies of this research from Professor Christopher Baker, Professor Sung Jang, Professor Jessica Westbrook, and Professor Adam Trowbridge. Very special gratitude goes out to Envisible members, Hyunwoo Bang, and Yunsil Heo who have provided me moral, emotional support. Keehong Youn is my MAT colleague and my roommate, we got over all the difficulties in the life in here Santa Barbara together. -

Korean Heritage

K O R E A N HERITAGE KOREAN HERITAGE Reclaim VOL 42 AUTUMN 2018 AUTUMN 2018 Vol.42 AUTUMN Cultural Heritage Administration Cultural Rediscovering Korea’s Early-modern History ISSN 2005-0151 www.koreanheritage.kr Korean Legation Government Publications Registration Number : 11-1550000-000639-08 Quarterly Magazine of the Cultural Heritage Administration KOREAN HERITAGE AUTUMN 2018 Vol.42 ON THE COVERS The Korean legation building in Washington, D.C. was stripped from Korean national ownership in 1910 when Japan forcefully annexed the country. After this traumatic loss, the building quickly emerged among the people of the Korean diaspora in the United States as a symbol of a sovereignty that should be regained by any means. They expressed their strong desire for independence by adding a large Korean national flag to a Korean legation postcard they produced during the Japanese colonial era (shown on the front cover). On May 22, 2018 the national flag was in reality hoisted from the roof of the newly restored Korean legation building (back cover). It was the fulfillment of a dream for the many Koreans who had KOREAN HERITAGE is also available on the website yearned for the reinstatement of this symbol of national autonomy, as well as for Emperor Gojong (www.koreanheritage.kr) and smart devices. You can also download and the members of his court who had attempted to forge a new future for the country through the its PDF version and subscribe to our newsletter to receive our latest introduction of advanced Western culture. news on the website. FEATURED ISSUE Cultural Heritage Administration, 2018 Rediscovering Korea’s Early-modern History This publication is copyrighted.