O Rigin Al a Rticle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. 165, October 2017

Journal of East Asian Libraries Volume 2017 | Number 165 Article 1 10-2017 Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. 165, October 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal BYU ScholarsArchive Citation (2017) "Journal of East Asian Libraries, No. 165, October 2017," Journal of East Asian Libraries: Vol. 2017 : No. 165 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jeal/vol2017/iss165/1 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the All Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of East Asian Libraries by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Journal of East Asian Libraries Journal of the Council on East Asian Libraries No. 165, October 2017 CONTENTS From the President 3 Essay A Tribute to John Yung-Hsiang Lai 4 Eugene W. Wu Peer-Review Articles An Overview of Predatory Journal Publishing in Asia 8 Jingfeng Xia, Yue Li, and Ping Situ Current Situation and Challenges of Building a Japanese LGBTQ Ephemera Collection at Yale Haruko Nakamura, Yoshie Yanagihara, and Tetsuyuki Shida 19 Using Data Visualization to Examine Translated Korean Literature 36 Hyokyoung Yi and Kyung Eun (Alex) Hur Managing Changes in Collection Development 45 Xiaohong Chen Korean R me for the Library of Congress to Stop Promoting Mccune-Reischauer and Adopt the Revised Romanization Scheme? 57 Chris Dollŏmaniz’atiŏn: Is It Finally Ti Reports Building a “One- 85 Paul W. T. Poon hour Library Circle” in China’s Pearl River Delta Region with the Curator of the Po Leung Kuk Museum 87 Patrick Lo and Dickson Chiu Interview 1 Web- 93 ProjectCollecting Report: Social Media Data from the Sina Weibo Api 113 Archiving Chinese Social Media: Final Project Report New Appointments 136 Book Review 137 Yongyi Song, Editor-in-Chief:China and the Maoist Legacy: The 50th Anniversary of the Cultural Revolution文革五十年:毛泽东遗产和当代中国. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Romancing race and gender : intermarriage and the making of a 'modern subjectivity' in colonial Korea, 1910-1945 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9qf7j1gq Author Kim, Su Yun Publication Date 2009 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Romancing Race and Gender: Intermarriage and the Making of a ‘Modern Subjectivity’ in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Literature by Su Yun Kim Committee in charge: Professor Lisa Yoneyama, Chair Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Jin-kyung Lee Professor Lisa Lowe Professor Yingjin Zhang 2009 Copyright Su Yun Kim, 2009 All rights reserved The Dissertation of Su Yun Kim is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2009 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page…………………………………………………………………...……… iii Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………... iv List of Figures ……………………………………………….……………………...……. v List of Tables …………………………………….……………….………………...…... vi Preface …………………………………………….…………………………..……….. vii Acknowledgements …………………………….……………………………..………. viii Vita ………………………………………..……………………………………….……. xi Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………. xii INTRODUCTION: Coupling Colonizer and Colonized……………….………….…….. 1 CHAPTER 1: Promotion of -

Yun Mi Hwang Phd Thesis

SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY Yun Mi Hwang A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2011 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/1924 This item is protected by original copyright This item is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence SOUTH KOREAN HISTORICAL DRAMA: GENDER, NATION AND THE HERITAGE INDUSTRY YUN MI HWANG Thesis Submitted to the University of St Andrews for the Degree of PhD in Film Studies 2011 DECLARATIONS I, Yun Mi Hwang, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 80,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in September 2006; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2006 and 2010. I, Yun Mi Hwang, received assistance in the writing of this thesis in respect of language and grammar, which was provided by R.A.M Wright. Date …17 May 2011.… signature of candidate ……………… I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. -

CKS NEWSLETTER Fall 2008

CKS NEWSLETTER Fall 2008 Center for Korean Studies, University of California, Berkeley Message from the Chair Dear Friends of CKS, Colleagues and Students: As we look forward to the thirtieth anniversary of the Center for Korean Studies (CKS) in 2009, we welcome our friends, colleagues, visiting scholars, and students to a year of new programs that we have scheduled for 2008–2009. In addition to continuing with the regular programs of past years, we began this year with the conference “Places at the Table,” an in-depth exploration of Asian women artists with a strong focus on Korean art. We presented a conference on “Reunification: Building Permanent Peace in Korea” (October 10) and a screening of the documentary film “Koryo Saram” (October 24). “Strong Voices,” a forum on Korean and American women poets, is scheduled for April 1–5, 2009. We are in the early planning stages for a dialogue on Korean poetry between Professor Robert Hass of UC Berkeley and Professor David McCann of Harvard, in conjunction with performances of Korean pansori and gayageum (September 2009). Providing that funding is approved by the Korea Foundation, an international conference on Korean Peninsula security issues (organized by Professor Hong Yung Lee) is also planned for next year. The list of colloquium speakers, conferences, seminars, and special events is now available on the CKS website. (See page 2 for the fall and spring schedule.) We welcome novelist Kyung Ran Jo as our third Daesan Foundation Writer-in-Residence. Ms Jo, whose novels have won many awards, will give lectures and share her writing with the campus community through December of this year. -

WIM Narratives of Modern and Contemporary Korea

KORGEN120_Zur 1 NARRATIVES OF MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY KOREA Tue/Thu 9:30‐10:45 Dr. Dafna Zur, [email protected] Office hours: Tuesdays 2:30‐3:30 and by appointment, Knight 312 Office number: 650‐725‐1893 Description This survey course of modern and contemporary narratives of Korea focuses on literary texts to gain insight into how the experience of being Korean was narrated and mediated in different periods of Korea’s modern history. Historically, the class will cover the colonial period, war and liberation, industrialization and urbanization, and the new millennium. We will engage in questions such as: • What is “modern” literature, and how might have “modernity” been experienced at the turn of the century? • What does it mean for a colonial subject to be writing fiction under conditions of censorship, and how are we to understand the rich production of textual and visual narratives during the colonial period? • What were some of the ways in which Korea experienced liberation and urbanization, and how does literature complicate our understanding of “progress”? • What has been the particularly gendered experience of Koreans in the new millennium, and how does language and culture continue to evolve under the rapidly transforming and changes in media? The students’ understanding of these issues will be enriched by assigned readings from other disciplines in order broaden the terms of our engagement with the primary texts and in order to consider the broad context of modern Korean religions, colonial and post-colonial history, and contemporary Korean culture and politics. Please note: • There is no Korean language requirement for the class. -

Read 2020 Book Lists

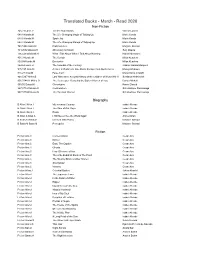

Translated Books - March - Read 2020 Non-Fiction 325.73 Luise.V Tell Me How It Ends Valeria Luiselli 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M Spark Joy Marie Kondo 648.8 Kondo.M The Life-Changing Manga of Tidying Up Marie Kondo 741.5944 Satra.M Embroideries Marjane Satrapi 784.2092 Ozawa.S Absolutely on Music Seiji Ozawa 796.42092 Murak.H What I Talk About When I Talk About Running Haruki Murakami 801.3 Kunde.M The Curtain Milan Kundera 809.04 Kunde.M Encounter Milan Kundera 864.64 Garci.G The Scandal of the Century Gabriel Garcia Marquez 915.193 Ishik.M A River In Darkness: One Man's Escape from North Korea Masaji Ishikawa 918.27 Crist.M False Calm Maria Sonia Cristoff 940.5347 Aleks.S Last Witnesses: An Oral History of the Children of World War II Svetlana Aleksievich 956.704431 Mikha.D The Beekeeper: Rescuing the Stolen Women of Iraq Dunya Mikhail 965.05 Daoud.K Chroniques Kamel Daoud 967.57104 Mukas.S Cockroaches Scholastique Mukasonga 967.57104 Mukas.S The Barefoot Woman Scholastique Mukasonga Biography B Allen.I Allen.I My Invented Country Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I The Sum of Our Days Isabel Allende B Allen.I Allen.I Paula Isabel Allende B Altan.A Altan.A I Will Never See the World Again Ahmet Altan B Khan.N Satra.M Chicken With Plums Marjane Satrapi B Satra.M Satra.M Persepolis Marjane Satrapi Fiction Fiction Aira.C Conversations Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Dinner Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ema, The Captive Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C Ghosts Cesar Aira Fiction Aira.C How I Became a Nun Cesar -

Contemporary Visions of the New Woman in Korean Literature by Mikayla George, Junior, Media the Concept Of

Contemporary Visions of the New Woman in Korean Literature By Mikayla George, junior, Media The concept of the “new woman” arose as a phenomenon in the early 20th century, emerging in Korea during the Japanese colonial period. This archetype was defined by a romanticism of the female as the most marginalized member of society, who could gain agency through modernization. In the Korean context, the new woman was associated with Westernization and modernity, and over time became ostracized and thought of as a negative consequence of modernity (Kim, 52). In contemporary Korean literature such as The Vegetarian by Han Kang, the colonial new woman archetype manifests in an individual whose disregard of traditional values leads to destructive consequences. Yeong-hye from The Vegetarian embodies the new woman through her subversion of traditional gender expectations and her struggle for bodily autonomy which culminates in a moment of transcendence of societal norms. In The Vegetarian, Yeong-hye’s subversions of gender norms are simultaneously fetishized and criticized, which echoes the treatment of new women during the colonial period. During the pivotal family dinner scene in Part I of the novel, Yeong-hye’s father forces a piece of meat into her mouth after slapping her and yelling at her repeatedly (Han 48). This moment of violence embodies not only her family and father’s disapproval of her transgression, but also the specific disapproval of her actions from men, and thus patriarchal society as a whole. This is represented through her father telling Yeong-hye’s husband and brother to hold her still when he force feeds her (Han 46). -

KOREA's LITERARY TRADITION 27 Like Much Folk and Oral Literature, Mask Dances Ch'unhyang Chòn (Tale of Ch'unhyang)

Korea’s Literary Tradition Bruce Fulton Introduction monks and the Shilla warrior youth known as hwarang. Corresponding to Chinese Tang poetry Korean literature reflects Korean culture, itself and Sanskrit poetry, they have both religious and a blend of a native tradition originating in Siberia; folk overtones. The majority are Buddhist in spirit Confucianism and a writing system borrowed from and content. At least three of the twenty-five sur- China; and Buddhism, imported from India by way viving hyangga date from the Three Kingdoms peri- of China. Modern literature, dating from the early od (57 B.C. – A.D. 667); the earliest, "Sòdong yo," 1900s, was initially influenced by Western models, was written during the reign of Shilla king especially realism in fiction and imagism and sym- Chinp'yòng (579-632). Hyangga were transcribed in bolism in poetry, introduced to Korea by way of hyangch'al, a writing system that used certain Japan. For most of its history Korean literature has Chinese ideographs because their pronunciation embodied two distinct characteristics: an emotional was similar to Korean pronunciation, and other exuberance deriving from the native tradition and ideographs for their meaning. intellectual rigor originating in Confucian tradition. The hyangga form continued to develop during Korean literature consists of oral literature; the Unified Shilla kingdom (667-935). One of the literature written in Chinese ideographs (han- best-known examples, "Ch'òyong ka" (879; “Song of mun), from Unified Shilla to the early twentieth Ch'òyong”), is a shaman chant, reflecting the influ- century, or in any of several hybrid systems ence of shamanism in Korean oral tradition and sug- employing Chinese; and, after 1446, literature gesting that hyangga represent a development of written in the Korean script (han’gùl). -

The Gendered Politics of Meat: Becoming Tree in Kang’S the Vegetarian, Atwood’S the Edible Woman and Ozeki’S My Year of Meats Notes Aline Ferreira 1

Série Alimentopia USDA - United States Department of Agriculture. (2015). Local Food Marketing Practices Survey. [on- line] URL: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Surveys/Guide_to_NASS_Surveys/Local_Food/, accessed on October 21st, 2019. Woolcock, M., & Narayan, D. (2000). Social capital: implications for development theory, research and policy. World Bank Research Observer, 15 (2), 225-249. The Gendered Politics of Meat: Becoming Tree in Kang’s The Vegetarian, Atwood’s The Edible Woman and Ozeki’s My Year of Meats Notes Aline Ferreira 1. Josué de Castro was a doctor, professor, geographer, sociologist and politician and he made the fight against hunger his life. Author of numerous iconic works, he revolutionised concepts of sustainable development and studied in depth the social injustices that caused misery, especially in Brazil. His best-known work and what has been used as a bibliography of this work is The Geopolitics of Hunger. 2. An inseparable union of four characteristics: ecologically sound, economically viable, socially fair and This essay addresses the vexed question of the gendered politics of meat, using three novels culturally accepted (Slow Food, 2013). that powerfully dramatise these issues as case studies: Margaret Atwood’s The Edible Woman 3. Manifesto of the international Slow Food movement of 1989, which maintains that food needs to be (1990), Ruth Ozeki’s My Year of Meats (1998) and – to be treated first – Han Kang’s The Vegetarian good, referring to the aroma and flavour, and the skill of the production not to change its naturalness; (2007). The topics of meat-eating and animal farming as well as the ways in which they intersect clean, referring to sustainable practices of cultivation, processing and marketing - all stages of the problematically with sexual politics are the main thematic concerns in the three novels, which production chain must protect biodiversity, the producer and the consumer; fair in the sense that can be seen as engaged in a critical dialogue. -

The Unificationist Funerary Tradition

religions Article The Unificationist Funerary Tradition Lukas Pokorny Department of Religious Studies, University of Vienna, 1010 Vienna, Austria; [email protected] Received: 22 April 2020; Accepted: 17 May 2020; Published: 20 May 2020 Abstract: This paper explores the distinctive funerary tradition of the Unification Movement, a globally active South Korean new religious movement founded in 1954. Its funerary tradition centres on the so-called Seonghwa (formerly Seunghwa) Ceremony, which was introduced in January 1984. The paper traces the doctrinal context and the origin narrative before delineating the ceremony itself in its Korean expression, including its preparatory and follow-up stages, as well as its short-lived adaptation for non-members. Notably, with more and more first-generation adherents passing away—most visibly in respect to the leadership culminating in the Seonghwa Ceremony of the founder himself in 2012—the funerary tradition has become an increasingly conspicuous property of the Unificationist lifeworld. This paper adds to a largely uncharted area in the study of East Asian new religious movements, namely the examination of their distinctive deathscapes, as spelled out in theory and practice. Keywords: Unification Church; funeral; death; ritual; new religious movement; Korea; East Asia 1. Introduction “‘Death’ is a sacred word. It is not a major expression for sorrow and pain. [ ::: ] The moment one enters the spiritual world is a time that one enters a world of joy and victory with the earthly life having blossomed, the fruits borne, and the grain ladled. It is a moment we [i.e., those staying behind] should rejoice. It should be a time when we celebrate wholeheartedly. -

I. Introduction

TRANSACTIONS ROYAL ASIATIC SOCIETY Korea Branch Volume 93 – 2018 1 COVER: The seal-shaped emblem of the RAS-KB consists of the following Chinese characters: 槿 (top right), 域 (bottom right), 菁 (top left), 莪 (bottom left), pronounced Kŭn yŏk Ch’ŏng A in Korean. The first two characters mean “the hibiscus region,” referring to Korea, while the other two (“luxuriant mugwort”) are a metaphor inspired by Confucian commentaries on the Chinese Book of Odes, and could be translated as “enjoy encouraging erudition.” SUBMISSIONS: Transactions invites the submission of manuscripts of both scholarly and more general interest pertaining to the anthropology, archeology, art, history, language, literature, philosophy, and religion of Korea. Manuscripts should be prepared in MS Word format and should be submitted in digital form. The style should conform to The Chicago Manual of Style (most recent edition). The covering letter should give full details of the author’s name, address and biography. Romanization of Korean words and names must follow either the McCune-Reischauer or the current Korean government system. Submissions will be peer- reviewed by two readers specializing in the field. Manuscripts will not be returned and no correspondence will be entered into concerning rejections. Transactions (ISSN 1229-0009) General Editor: Jon Dunbar Copyright © 2019 Royal Asiatic Society – Korea Branch Room 611, Christian Building, Daehangno 19 (Yeonji-dong), Jongno-gu, Seoul 110-736 Republic of Korea Tel: (82-2) 763-9483; Fax: (82-2) 766-3796; Email: [email protected] Visit our website at www.raskb.com TRANSACTIONS Volume 93 – 2018 Contents The Diamond Mountains: Lost Paradise Brother Anthony 1 Encouragement from Dongducheon 19 North Korean Fragments of Post-Socialist Guyana Moe Taylor 31 The Gyehu Deungnok Mark Peterson 43 “Literature Play” in a New World Robert J. -

Spring 2011 Vol. 4 No. 1

C M Y K Spring 2011 Vol. 4 No. 1 Spring 2011 Vol. 4 No. 1 Vol. ISSNISBN 2005-0151 C M Y K Quarterly Magazine of the Cultural Heritage Administration Spring 2011 Vol. 4 No. 1 Cover Blue symbolizes spring. The symbolism originates from the traditional “five direc- tional colors” based on the ancient Chinese thought of wuxing, or ohaengohaeng in Korean. The five colors were associated with seasons and other phenomena in nature, including the fate of humans. The cover design fea- tures phoenixes or bonghwang, a popular motif in Korean traditional arts. For more stories about animal symbols, see p. 22. KOREAN HERITAGE is also available on the website. ( http://english.cha.go.kr ) CHA New Vignettes KoreAN FolK Customs Choe Takes Office as New Administrator Five Colors and Five Flavors: Bibimbap for Global Gourmets Choe Kwang-shik, former director of the National Museum of Korea, was appointed Traditional Korean dishes are characterized by an orchestration of rich colors and new administrator of the Cultural Heritage Administration on February 9. He suc- flavors. They often harmonize the five fundamental colors of blue, white, black, red ceeded Yi Kun-moo, who served as CHA administrator for the past 35 months. In his and yellow, deriving from the East Asian philosophy of the “five phases” (ohaeng, or inaugural address, Mr. Choe emphasized international exchange of cultural heritage, wuxing in Chinese). These colors are associated with the five cardinal directions of social role of cultural heritage, transparent cultural heritage administration and culti- east, west, north, south and center; they are also related with the five basic flavors and vation of specialized human resources.