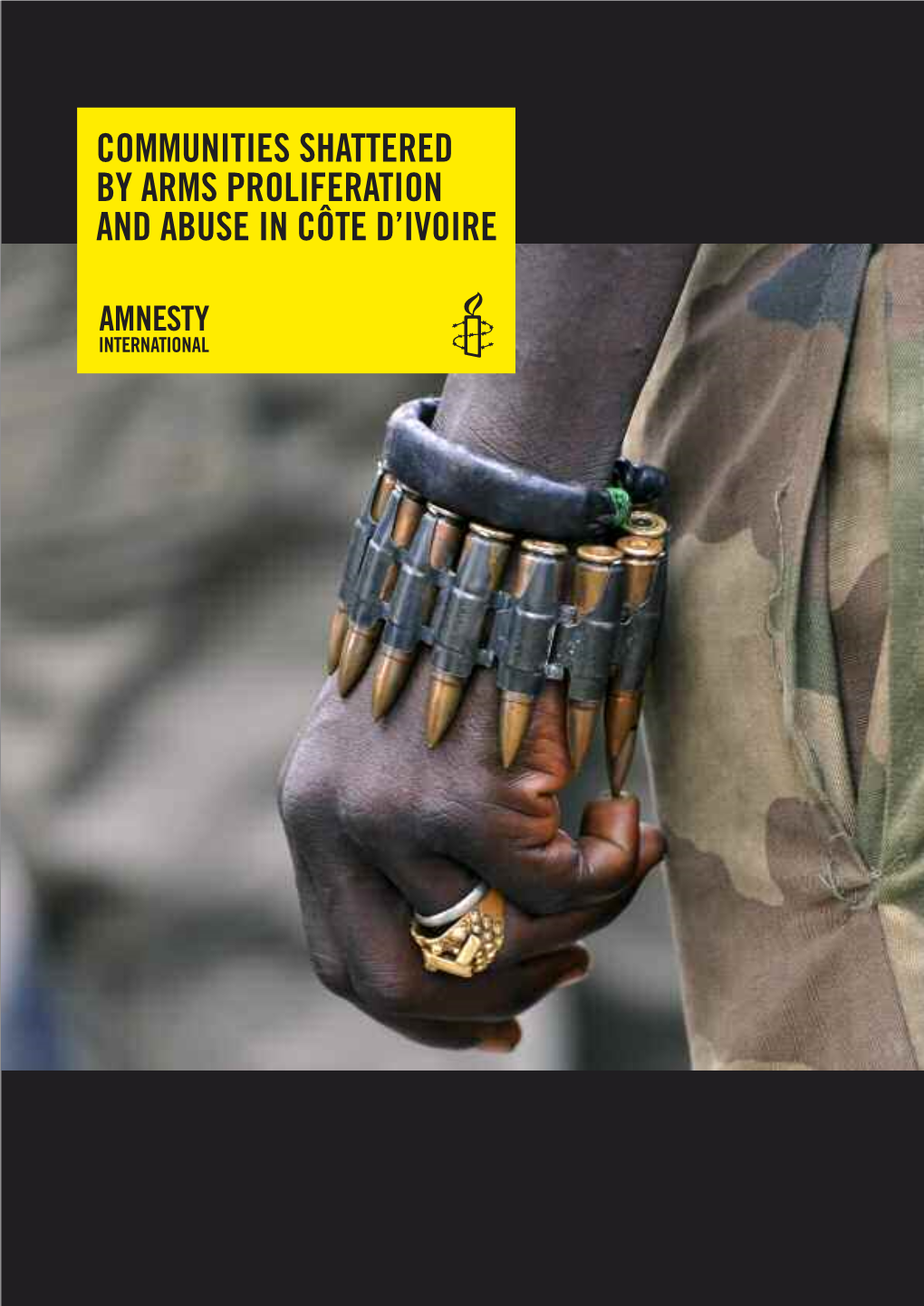

Communities Shattered by Arms Proliferation and Abuse in Côte D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions”

“Abidjan: Floods, Displacements, and Corrupt Institutions” Abstract Abidjan is the political capital of Ivory Coast. This five million people city is one of the economic motors of Western Africa, in a country whose democratic strength makes it an example to follow in sub-Saharan Africa. However, when disasters such as floods strike, their most vulnerable areas are observed and consequences such as displacements, economic desperation, and even public health issues occur. In this research, I looked at the problem of flooding in Abidjan by focusing on their institutional response. I analyzed its institutional resilience at three different levels: local, national, and international. A total of 20 questionnaires were completed by 20 different participants. Due to the places where the respondents lived or worked when the floods occurred, I focused on two out of the 10 communes of Abidjan after looking at the city as a whole: Macory (Southern Abidjan) and Cocody (Northern Abidjan). The goal was to talk to the Abidjan population to gather their thoughts from personal experiences and to look at the data published by these institutions. To analyze the information, I used methodology combining a qualitative analysis from the questionnaires and from secondary sources with a quantitative approach used to build a word-map with the platform Voyant, and a series of Arc GIS maps. The findings showed that the international organizations responded the most effectively to help citizens and that there is a general discontent with the current local administration. The conclusions also pointed out that government corruption and lack of infrastructural preparedness are two major problems affecting the overall resilience of Abidjan and Ivory Coast to face this shock. -

Child from Treichville

The "terrible" child from Treichville Musical lives in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire Bente E. Aster Hovedfagsoppgave i sosialantropologi Høst 2004. Universitetet i Oslo Summary In this thesis I investigate modern music genres and performance practices in Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. I worked with three band structures, within three different genres: The local pop genre zouglou, the dancehall genre and the reggae genre. I have especially concentrated on reggae, and I compare how it is played and performed in Côte d’Ivoire to how it is perceived in Jamaica. Interestingly enough, reggae sounds different in the two countries, and in my thesis I hope to show the various reasons for this phenomenon. I am interested in the questions: Why do Ivorians listen to reggae, and what do they do in order to adapt it to the Ivorian setting? I claim that a certain social environment produces certain aesthetical preferences and performance practices. In short it produces taste: History and taste go together. Thus styles are historically constructed identity marks. Christopher Waterman has linked various social histories to musical genres and tastes in Nigeria in interesting ways (Waterman 1990). The Ivorian setting creates a sound that is denser and involves a heavier orchestration than the Jamaican one, which is cut down to the core. The two countries have different points of departure and different histories, and one can hear the traces of this in the two versions of reggae. Global inspirations become local expressions to Ivorians. Singers must uphold their local credibility and authenticity, and thereby create a resonance between themselves and their audience. -

No. ICC-02/11 23 June 2011 Original

ICC-02/11-3 23-06-2011 1/80 EO PT Original: English No .: ICC-02/11 Date: 23 June 2011 PRE-TRIAL CHAMBER III Before: Judge Odio Benito Judge Adrian Fulford Judge Silvia Fernandez de Gurmendi SITUATION IN THE REPUBLIC OF CÔTE D'IVOIRE Public Document Request for authorisation of an investigation pursuant to article 15 Source: Office of the Prosecutor No. ICC-02/11 1/80 23 June 2011 ICC-02/11-3 23-06-2011 2/80 EO PT Document to be notified in accordance with regulation 31 of the Regulations of the Court to: The Office of the Prosecutor Counsel for the Defence Legal Representatives of the Victims Legal Representatives of the Applicants Unrepresented Victims Unrepresented Applicants (Participation/Reparation) The Office of Public Counsel for The Office of Public Counsel for the Victims Defence States’ Representatives Amicus Curiae REGISTRY Registrar Defence Support Section Silvana Arbia Deputy Registrar Victims and Witnesses Unit Detention Section Victims Participation and Reparations Other Section No. ICC-02/11 2/80 23 June 2011 ICC-02/11-3 23-06-2011 3/80 EO PT I. Introduction 1. The Prosecutor hereby requests authorization from the Pre-Trial Chamber to proceed with an investigation into the situation in the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire since 28 November 2010, pursuant to Article 15(3) of the Rome Statute. 2. Violence has reached unprecedented levels in the aftermath of the presidential election held on 28 November 2010. There is a reasonable basis to believe that at least 3000 persons were killed, 72 persons disappeared, 520 persons were subject to arbitrary arrest and detentions and there are over 100 reported cases of rape, while the number of unreported incidents is believed to be considerably higher. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Abidjan Urban Mobility Project (P167401) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Combined Project Information Documents / Integrated Safeguards Datasheet (PID/ISDS) Appraisal Stage | Date Prepared/Updated: 08-May-2019 | Report No: PIDISDSA26942 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Apr 24, 2019 Page 1 of 26 The World Bank Abidjan Urban Mobility Project (P167401) BASIC INFORMATION OPS_TABLE_BASIC_DATA A. Basic Project Data Country Project ID Project Name Parent Project ID (if any) Cote d'Ivoire P167401 Abidjan Urban Mobility Project Region Estimated Appraisal Date Estimated Board Date Practice Area (Lead) AFRICA 06-May-2019 28-Jun-2019 Transport Financing Instrument Borrower(s) Implementing Agency Investment Project Financing THE REPUBLIC OF COTE Ministry of Transport D’IVOIRE Proposed Development Objective(s) The Project Development Objective is to improve accessibility to economic and social opportunities and to increase efficiency of the public transport system along the Yopougon-Bingerville corridor and its feeder lines in Abidjan. Components Implementation of the East West BRT Yopougon-Bingerville Strengthening of SOTRA and restructuring of the feeder system to mass transit lines Organisation of the informal transport sector and last mile accessibility Human Capital Development and Operational Support PROJECT FINANCING DATA (US$, Millions) SUMMARY-NewFin1 Total Project Cost 540.00 Total Financing 540.00 of which IBRD/IDA 300.00 Financing Gap 0.00 DETAILS-NewFinEnh2 Private Sector Investors/Shareholders Equity Amount Debt Amount Government Contribution 10.00 IFI Debt 400.00 Apr 24, 2019 Page 2 of 26 The World Bank Abidjan Urban Mobility Project (P167401) Government Resources 10.00 IDA (Credit/Grant) 300.00 Non-Government Contributions 40.00 Other IFIs 100.00 Private Sector Equity 40.00 Commercial Debt 90.00 Unguaranteed 90.00 Total 50.00 490.00 Payment/Security Guarantee Total 0.00 Environmental Assessment Category A-Full Assessment Decision The review did authorize the team to appraise and negotiate B. -

Cote D'ivoire GREATER ABIDJAN PORT - CITY INTEGRATION PROJECT

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Report No: PAD2771 Public Disclosure Authorized INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED SCALE-UP FACILITY CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF EURO 260.5 MILLION (US$315 MILLION EQUIVALENT) Public Disclosure Authorized TO THE REPUBLIC OF CÔTE D’IVOIRE FOR THE GREATER ABIDJAN PORT - CITY INTEGRATION PROJECT June 7, 2018 Public Disclosure Authorized Transport and Digital Development Global Practice Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective April 30, 2018) Currency Unit = EUR O US$1 = Euro 0.826984 US$1 = SDR 0.695380 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 Regional Vice President: Makhtar Diop Country Director: Pierre Frank Laporte Senior Global Practice Director: Jose Luis Irigoyen Practice Manager: Nicolas Peltier-Thiberge Task Team Leaders: Hatem Chahbani, Mahine Diop, Mohamadou S Hayatou ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AAC Abidjan Addressing Center AADT Annual Average Daily Traffic ABWP Annual Budgeted Work Plan AF Additional Financing AFD French Development Agency (Agence française de développement) AfDB African Development Bank AGEROUTE Road Management Agency (Agence de gestion des routes) ALP Abidjan Logistics Platform ASA Advisory Services and Analytics BNETD National Bureau for Technical Studies and Development (Bureau -

The Toxic Truth

THE TOXIC TRUTH ABOUT A COMPANY CALLED TRAFIGURA, A SHIP CALLED THE PROBO KOALA, AND THE DUMPING OF TOXIC WASTE IN CÔTE D’IVOIRE THE TOXIC TRUTH ABOUT A COMPANY CALLED TRAFIGURA, A SHIP CALLED THE PROBO KOALA, AND THE DUMPING OF TOXIC WASTE IN CÔTE D’IVOIRE 2 AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL AND GREENPEACE NETHERLANDS This is a story of corporate crime, human rights abuse and governments’ failure to protect people and the environment. It is a story that exposes how systems for enforcing international law have failed to keep up with companies that operate trans-nationally, and how one company has been able to take full advantage of legal uncertainties and jurisdictional loopholes, with devastating consquences. For the people at the centre of the story – the people of Abidjan in Côte d’Ivoire – it starts with horror and ends in tragedy. It began on 20 August 2006 when they woke up to find that foul-smelling, toxic waste had been dumped in numerous places around their city. Tens of thousands of people suffered from nausea, headaches, breathing difficulties, stinging eyes and burning skin. They did not know what was happening; they were terrified. Health centres and hospitals were soon overwhelmed. International agencies were drafted in to help overstretched local medical staff. More than 100,000 people were treated, according to official records, but it is likely that the number affected was higher as records are incomplete. The authorities reported that between 15 and 17 people died. With medical treatment and time, the symptoms abated, but for many the fear remains. -

Border Operations Between Abidjan (Côte D'ivoire) and Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso)

Experience of cross- border operations between Abidjan (Côte d'Ivoire) and Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso) Simplice ESSOH SITARAIL Context and operational regulation framework NETWORK INFORMATION NETWORK OPERATION Traffic data and employees 1904 : Abidjan – Ouagadougou line opening o 150 000 Passenger/year Operated by RAN (Régie Abidjan – Niger) o 900 000 tons/year 1 500 employees o 1989 : Transfer of activities to Société Ivoirienne des Chemins de Fer (Ivory Coast) and la Société des Chemins de Network data: Fer Burkinabé (Burkina Faso) for 6 years o 1260 kms metric gauge 1995 : SITARAIL (Bolloré Group) under “affermage” regime. o 40 locomotives o 1 200 wagons o 59 stations o 50km/h freight train speed REGULATION FRAMEWORK o 60Km/h passenger train speed . Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso apply UEMOA regulation which allows the free movement of people and freight. However both Countries still maintain cross border police and customs control. Two specific regulations for international railway traffic: . 1991 : Railway international transit regime (TIF) for freight traffic between the two Countries . 1997 : Legal agreement for train operations at border point. 2 SITARAIL Border crossing procedures Border crossing station Freight transport Passenger transport Customs control Ouangolo (Ivory Coast) . Platform visual checking . Police control (ID verification, etc.) . Checking application of TIF regime . Ivory Coast health control (Vaccine,..) . Validation of TIF (paper document) . Customs control (Luggage,..) Niangoloko (Burkina Faso) Live stock veterinary control . The two stations are 44 kms far from each other . Freight transport : 02 customs controls for each train, which corresponds to 3 hours stop for each train, equivalent to 5% of transit time Abidjan-Ouaga . -

West Africa West Africa

Last update: 29 Jan. 17 rev. February 8 by West Africa West Africa Funding acknowledgement Each publication, press release, or other document about research supported by an NIH award must include an acknowledgment of NIH award support and a disclaimer such as “Research reported in this publication was supported by the US National Institutes of Health (NIAID, NICHD, NCI and NIMH) under Award Number U01AI069919 (PI: Dabis). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.” Prior to issuing a press release concerning the outcome of this research, please notify the NIH awarding Institute/Centre in advance to allow for coordination. Site investigators and cohorts: Adult cohorts: Marcel Djimon Zannou, CNHU, Cotonou, Benin; Armel Poda, CHU Souro Sanou, Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso; Fred Stephen Sarfo & Komfo Anokeye Teaching Hospital, Kumasi, Ghana; Eugene Messou, ACONDA CePReF, Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire; Henri Chenal, CIRBA, Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire; Kla Albert Minga, CNTS, Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire; Emmanuel Bissagnene, & Aristophane Tanon, CHU Treichville, Cote d’Ivoire; Moussa Seydi, CHU de Fann, Dakar, Senegal; Akessiwe Akouda Patassi, CHU Sylvanus Olympio, Lomé, Togo. Pediatric cohorts: Sikiratou Adouni Koumakpai-Adeothy,_CNHU, Cotonou, Benin; Lorna Awo Renner, Korle Bu Hospital, Accra, Ghana; Sylvie Marie N’Gbeche, ACONDA CePReF, Abidjan, Ivory Coast; Clarisse Amani Bosse, ACONDA_MTCT+, Abidjan, Ivory Coast; Kouadio Kouakou, CIRBA, Abidjan, Cote -

Obstacles to Social Cohesion and Dynamics of Youth Violence in Urban Spaces

RESUME E X ECUTIF JUILLET 2015 2 inforinmfoartionmation and and vie viewwss exprresedessed the thereinr liesein e liesntir elyen withtirely those with consul thoseted c onsuland theted author ands .the authors. JUILLET 2015 RESUME EXECUTIF 3 Contents R exécutif 6 Executive Summary Au-delà de la recherche, un travail de rapprochement et de Beyondd rredéconstructionesseeaarrcchh, ,a a w woor rkdesk o of imaginaifr arappprorcorhces..............................................ehmemenetn at nadn dim imagaingianrayr d..............................................ye dcoecnostnrsutcrtuioctnion 9 Au-delà du diagnostic, des actions pour le changement............................................ Beyondd tthhee ddiiaaggnnoossisis, ,a acctitoionns sf ofor rc hchanagneg e 10 The challeLen gdée aih àe raelde:v Aer: ra unpp rrappochreochementment bet wenteeren lesthe au autorithotésri teties and the people The challenge ahead: A rapprochement between the authorities and the people les populations.............................................................................................................................. 11 The electoral context and programmatic urgency The electPoerspectral conivteesx télec andto pralesrog reta murmgenceatic purroggernammatique................................................cy 12 Recommendations and avenues for re�lection RecomRmecommandationsendations and av eetn upisest fesor de re rléectleixionon 14 The bus station and the actors that are operating around it The bus stAautitoourn a nded tlah equestion actors t hdeat -

Final Report

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) Ministry of Construction, Housing, Sanitation and Urban Development (MCLAU) The Project for the Development of the Urban Master Plan in Greater Abidjan in the Republic of Côte d’Ivoire (SDUGA) Final Report March 2015 Volume III Urban Transport Master Plan Appendices Appendix A (Page A-1 to A-27) Zoning System for Transport Surveys 4 digit (2digit +2digit) Region/CQUARTIER Alphabetical Sequence Zone Code COMMUNE QUARTIER/Ville Ville/landmark 01 01 1.ABOBO ABOBO-BAOULE 01 02 (Commune) ABOBO-CENTRE 01 03 ABOBO-DOKUI 01 04 ABOBO-NORD SETU 01 05 ABOBO-SUD 2EME TRANCHE 01 06 ABOBO SUD 3è TRANCHE 01 07 ABOBO-TE 01 08 AGBEKOI 01 09 AGNISSANKOI AVOCATIER 01 10 AGOUETO 01 11 AKEIKOI 01 12 ANADOR 01 13 ANONKOI III 01 14 ANONKOI-KOUTE 01 15 AVOCATIER N'GUESSANKOI 01 16 BANCO 1 & 2 01 17 CENT DOUZE HECTARES 01 18 CLOUETCHA KENNEDY 01 19 DJIBI 01 20 EXTENSION C 01 21 HOUPHOUET BOIGNY 01 22 N'PONON 01 23 PLAQUE 1 ET 2 01 24 SAGBE CENTRE 01 25 SAGBE NORD 01 26 SAGBE SUD 01 27 SANS MANQUER 01 28 SOGEFIHA HABITAT 01 99 Not Identify 02 01 2.ADJAME 220 LOGEMENTS 02 02 (Commune) ADJAME-CIMETIERE OU MARIE THER 02 03 ADJAME-NORD 02 04 ADJAME-NORD-EST OU BRACODI 02 05 ADJAME-VILLAGE 02 06 BROMAKOTE OU PELLIEUVILLE 02 07 DALLAS 02 08 EBRIE 02 09 HABITAT-EXTENSION 02 10 INDENIE 02 11 MAIRIE 1 02 12 MAIRIE 2 02 13 MIRADOR 02 14 PAILLET 02 15 ST-MICHEL 02 16 SODECI FILTISAC 02 17 WILLIAMSVILLE 1 02 18 WILLIAMSVILLE 2 02 19 WILLIAMSVILLE 3 UNIVERSITE ADJ 02 99 Not Identify 03 01 3.ATTECOUBE ABOBO-DOUME VILLAGE 03 02 (Commune) -

Project Information Document

The World Bank Abidjan Urban Mobility Project (P167401) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Project Information Document/ Integrated Safeguards Data Sheet (PID/ISDS) Concept Stage | Date Prepared/Updated: 19-Oct-2018 | Report No: PIDISDSC24943 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Sep 17, 2018 Page 1 of 21 The World Bank Abidjan Urban Mobility Project (P167401) BASIC INFORMATION A. Basic Project Data OPS TABLE Country Project ID Parent Project ID (if any) Project Name Cote d'Ivoire P167401 Abidjan Urban Mobility Project (P167401) Region Estimated Appraisal Date Estimated Board Date Practice Area (Lead) AFRICA Jun 03, 2019 Jun 28, 2019 Transport & Digital Development Financing Instrument Borrower(s) Implementing Agency Investment Project Financing THE REPUBLIC OF COTE Ministry of Transport D’IVOIRE Proposed Development Objective(s) The Project Development Objective is to improve accessibility to opportunities and to increase efficiency of the public transport system along the Yopougon-Bingerville corridor and its feeder lines in Abidjan. PROJECT FINANCING DATA (US$, Millions) SUMMARY-NewFin1 Total Project Cost 350.00 Total Financing 300.00 of which IBRD/IDA 300.00 Financing Gap 50.00 DETAILS-NewFinEnh1 World Bank Group Financing International Development Association (IDA) 300.00 IDA Credit 300.00 Environmental Assessment Category Concept Review Decision A - Full Assessment Track II-The review did authorize the preparation to continue Sep 17, 2018 Page 2 of 21 The World Bank Abidjan Urban Mobility Project (P167401) Other Decision (as needed) B. Introduction and Context Country Context Côte d’Ivoire is in the midst of a healthy recovery from a decade-long civil war. The country is the largest economy in francophone Sub-Saharan Africa, and the third-largest in West Africa, with a population of 24.3 million and a gross domestic product (GDP) of US$39.91 billion in 2017. -

Analysis of the Incidence of the Deficit of Sanitation on the Health of the Populations in a Context of Urban Growth: Case of Th

Vol. 9(6), pp. 50-58, June 2017 DOI: 10.5897/JTEHS2017.0390 Article Number: 644DFEC64800 Journal of Toxicology and Environmental ISSN 2006-9820 Copyright © 2017 Health Sciences Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/JTEHS Full Length Research Paper Analysis of the incidence of the deficit of sanitation on the health of the populations in a context of urban growth: Case of the municipalities Yopougon, Abobo and Treichville' (Abidjan, Ivory Coast) Yapo Toussaint Wolfgang1, 2*, Amin N’cho Christophe1,3, Yapo Ossey Bernard2, and Mambo Veronique2 1National Institut of Public Health (NIPH), BPV 14, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. 2Laboratoire of Sciences Environment, Group of Research in Chemistry Water, Nangui Abrogoua University, 02 BP 801 Abidjan 02, Côte d’Ivoire. 3Department of Pharmaceutical and Biological Sciences, University of Cocody, Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. Received 6 April, 2017; Accepted 2 June, 2017 The emergence of pathologies and their impacts on the health of the populations were studied in the municipalities of Yopougon, Abobo, and Treichville. This study highlights the conditions of noxious life and the health of the populations. To achieve this, a transverse investigation with the households was conducted on 300 households in 2013. It is concerned with the sources of water supply. It was noticed that 80% of the households from the municipality of Abobo, 90% from Yopougon, and 85% from Treichville use the water from public adduction network. Besides, in these municipalities, the mode of management of waste water is to eliminate the waste through autonomous works, collective works or nature. So in these municipalities, a retrospective study was made on these sanitary data registered in health centers during these years.