NC10 Phylum Anaerobs? Methanotrophs? Where Can I Find Them?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spatio-Temporal Study of Microbiology in the Stratified Oxic-Hypoxic-Euxinic, Freshwater- To-Hypersaline Ursu Lake

Spatio-temporal insights into microbiology of the freshwater-to- hypersaline, oxic-hypoxic-euxinic waters of Ursu Lake Baricz, A., Chiriac, C. M., Andrei, A-., Bulzu, P-A., Levei, E. A., Cadar, O., Battes, K. P., Cîmpean, M., enila, M., Cristea, A., Muntean, V., Alexe, M., Coman, C., Szekeres, E. K., Sicora, C. I., Ionescu, A., Blain, D., O’Neill, W. K., Edwards, J., ... Banciu, H. L. (2020). Spatio-temporal insights into microbiology of the freshwater-to- hypersaline, oxic-hypoxic-euxinic waters of Ursu Lake. Environmental Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14909, https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.14909 Published in: Environmental Microbiology Document Version: Peer reviewed version Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2019 Wiley. This work is made available online in accordance with the publisher’s policies. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. -

Yu-Chen Ling and John W. Moreau

Microbial Distribution and Activity in a Coastal Acid Sulfate Soil System Introduction: Bioremediation in Yu-Chen Ling and John W. Moreau coastal acid sulfate soil systems Method A Coastal acid sulfate soil (CASS) systems were School of Earth Sciences, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC 3010, Australia formed when people drained the coastal area Microbial distribution controlled by environmental parameters Microbial activity showed two patterns exposing the soil to the air. Drainage makes iron Microbial structures can be grouped into three zones based on the highest similarity between samples (Fig. 4). Abundant populations, such as Deltaproteobacteria, kept constant activity across tidal cycling, whereas rare sulfides oxidize and release acidity to the These three zones were consistent with their geological background (Fig. 5). Zone 1: Organic horizon, had the populations changed activity response to environmental variations. Activity = cDNA/DNA environment, low pH pore water further dissolved lowest pH value. Zone 2: surface tidal zone, was influenced the most by tidal activity. Zone 3: Sulfuric zone, Abundant populations: the heavy metals. The acidity and toxic metals then Method A Deltaproteobacteria Deltaproteobacteria this area got neutralized the most. contaminate coastal and nearby ecosystems and Method B 1.5 cause environmental problems, such as fish kills, 1.5 decreased rice yields, release of greenhouse gases, Chloroflexi and construction damage. In Australia, there is Gammaproteobacteria Gammaproteobacteria about a $10 billion “legacy” from acid sulfate soils, Chloroflexi even though Australia is only occupied by around 1.0 1.0 Cyanobacteria,@ Acidobacteria Acidobacteria Alphaproteobacteria 18% of the global acid sulfate soils. Chloroplast Zetaproteobacteria Rare populations: Alphaproteobacteria Method A log(RNA(%)+1) Zetaproteobacteria log(RNA(%)+1) Method C Method B 0.5 0.5 Cyanobacteria,@ Bacteroidetes Chloroplast Firmicutes Firmicutes Bacteroidetes Planctomycetes Planctomycetes Ac8nobacteria Fig. -

Bacteria Clostridia Bacilli Eukaryota CFB Group

AM935842.1.1361 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY283260.1.1552 Alcaligenes sp. PCNB−2 Class Betaproteobacteria AM934953.1.1374 uncultured Burkholderiales bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581593.1.1460 uncultured betaAM936569.1.1351 proteobacterium uncultured Class Betaproteobacteria Derxia sp. Class Betaproteobacteria AJ581621.1.1418 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ248272.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium soil uncultured DQ248272.1.1498 DQ248235.1.1498 uncultured soil bacterium RS49 DQ248270.1.1496 uncultured soil bacterium DQ256489.1.1211 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax DQ256489.1.1211 AF523053.1.1486 uncultured Comamonadaceae bacterium Class Betaproteobacteria AY706442.1.1396 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY706442.1.1396 AJ536763.1.1422 uncultured bacterium CS000359.1.1530 Variovorax paradoxus Class Betaproteobacteria Class paradoxus Variovorax CS000359.1.1530 AY168733.1.1411 uncultured bacterium AJ009470.1.1526 uncultured bacterium SJA−62 Class Betaproteobacteria Class SJA−62 bacterium uncultured AJ009470.1.1526 AY212561.1.1433 uncultured bacterium D16212.1.1457 Rhodoferax fermentans Class Betaproteobacteria Class fermentans Rhodoferax D16212.1.1457 AY957894.1.1546 uncultured bacterium AJ581620.1.1452 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria RS76 AY625146.1.1498 uncultured bacterium RS65 DQ316832.1.1269 uncultured beta proteobacterium Class Betaproteobacteria DQ404909.1.1513 uncultured bacterium uncultured DQ404909.1.1513 AB021341.1.1466 bacterium rM6 AJ487020.1.1500 uncultured bacterium uncultured AJ487020.1.1500 RS7 RS86RC AF364862.1.1425 bacterium BA128 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957931.1.1529 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957931.1.1529 CP000884.723807.725332 Delftia acidovorans SPH−1 Class Betaproteobacteria AY957923.1.1520 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957923.1.1520 RS18 AY957918.1.1527 uncultured bacterium uncultured AY957918.1.1527 AY945883.1.1500 uncultured bacterium AF526940.1.1489 uncultured Ralstonia sp. -

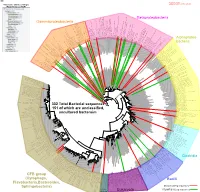

The Phylogenetic Composition and Structure of Soil Microbial Communities Shifts in Response to Elevated Carbon Dioxide

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy The ISME Journal (2012) 6, 259–272 & 2012 International Society for Microbial Ecology All rights reserved 1751-7362/12 www.nature.com/ismej ORIGINAL ARTICLE The phylogenetic composition and structure of soil microbial communities shifts in response to elevated carbon dioxide Zhili He1, Yvette Piceno2, Ye Deng1, Meiying Xu1,3, Zhenmei Lu1,4, Todd DeSantis2, Gary Andersen2, Sarah E Hobbie5, Peter B Reich6 and Jizhong Zhou1,2 1Institute for Environmental Genomics, Department of Botany and Microbiology, University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, USA; 2Ecology Department, Earth Sciences Division, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Berkeley, CA, USA; 3Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Microbial Culture Collection and Application, Guangdong Institute of Microbiology, Guangzhou, China; 4College of Life Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China; 5Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Behavior, St Paul, MN, USA and 6Department of Forest Resources, University of Minnesota, St Paul, MN, USA One of the major factors associated with global change is the ever-increasing concentration of atmospheric CO2. Although the stimulating effects of elevated CO2 (eCO2) on plant growth and primary productivity have been established, its impacts on the diversity and function of soil microbial communities are poorly understood. In this study, phylogenetic microarrays (PhyloChip) were used to comprehensively survey the richness, composition and structure of soil microbial communities in a grassland experiment subjected to two CO2 conditions (ambient, 368 p.p.m., versus elevated, 560 p.p.m.) for 10 years. The richness based on the detected number of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) significantly decreased under eCO2. -

Being Aquifex Aeolicus: Untangling a Hyperthermophile's Checkered Past

GBE Being Aquifex aeolicus: Untangling a Hyperthermophile’s Checkered Past Robert J.M. Eveleigh1,2, Conor J. Meehan1,2,JohnM.Archibald1, and Robert G. Beiko2,* 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada 2Faculty of Computer Science, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada *Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected]. Accepted: November 22, 2013 Abstract Lateral gene transfer (LGT) is an important factor contributing to the evolution of prokaryotic genomes. The Aquificae are a hyper- thermophilic bacterial group whose genes show affiliations to many other lineages, including the hyperthermophilic Thermotogae, the Proteobacteria, and the Archaea. Previous phylogenomic analyses focused on Aquifex aeolicus identified Thermotogae and Downloaded from Aquificae either as successive early branches or sisters in a rooted bacterial phylogeny, but many phylogenies and cellular traits have suggested a stronger affiliation with the Epsilonproteobacteria. Different scenarios for the evolution of the Aquificae yield different phylogenetic predictions. Here, we outline these scenarios and consider the fit of the available data, including three sequenced Aquificae genomes, to different sets of predictions. Evidence from phylogenetic profiles and trees suggests that the Epsilonproteobacteria have the strongest affinities with the three Aquificae analyzed. However, this pattern is shown by only a http://gbe.oxfordjournals.org/ minority of encoded proteins, and the Archaea, many lineages of thermophilic bacteria, and members of genus Clostridium and class Deltaproteobacteria also show strong connections to the Aquificae. The phylogenetic affiliations of different functional subsystems showed strong biases: Most but not all genes implicated in the core translational apparatus tended to group Aquificae with Thermotogae, whereas a wide range of metabolic and cellular processes strongly supported the link between Aquificae and Epsilonproteobacteria. -

The Environment, Diversity and Activity of Microbial Communities in Submarine Freshwater Springs in the Dead Sea

The environment, diversity and activity of microbial communities in submarine freshwater springs in the Dead Sea Dissertation Zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Naturwissenschaften - Dr. rer. nat. - dem Fachbereich Geowissenschaften der Universität Bremen vorgelegt an Stefan Häusler Bremen, April 2014 Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde in der Zeit von November 2010 bis April 2014 am Max- Planck-Institut für Marine Mikrobiologie in Bremen angefertigt. 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Marcel M.M. Kuypers 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Thorsten Dittmar Datum des Promotionskolloquiums: 16. Mai 2014 Contents Summary 1 Zusammenfassung 3 Chapter 1 7 Introduction 7 Motivation and objectives 23 Overview of enclosed manuscripts 35 Chapter 2 39 Microbial and chemical characterization of underwater fresh water springs in the Dead Sea Chapter 3 105 Microenvironments of reduced salinity harbor biofilms in Dead Sea underwater springs Chapter 4 125 Spatial distribution of diatom and cyanobacterial microbial mats in the Dead Sea is determined by response to rapid salinity fluctuations Chapter 5 153 Sulfate reduction and sulfide oxidation in extremely steep salinity gradients formed by freshwater springs emerging into the Dead Sea Chapter 6 189 Conclusions and perspectives Contributed work 201 Acknowledgements 211 Summary Summary The Dead Sea, located at the border between Jordan, Israel and the Palestinian authority is one of the most hypersaline lakes on earth. Its waters contain a total dissolved salt concentration of up to 348 g L-1, which is about 10 times higher than regular sea water. The lake is characterized by elevated concentrations of divalent cations (~2 M Mg2+ and ~0.5 M Ca2+), which, in addition to the high salinity, form an extreme environment where only highly adapted microorganisms can survive. -

1 Supplementary Material a Major Clade of Prokaryotes with Ancient

Supplementary Material A major clade of prokaryotes with ancient adaptations to life on land Fabia U. Battistuzzi and S. Blair Hedges Data assembly and phylogenetic analyses Protein data set: Amino acid sequences of 25 protein-coding genes (“proteins”) were concatenated in an alignment of 18,586 amino acid sites and 283 species. These proteins included: 15 ribosomal proteins (RPL1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 11, 13, 16; RPS2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11), four genes (RNA polymerase alpha, beta, and gamma subunits, Transcription antitermination factor NusG) from the functional category of Transcription, three proteins (Elongation factor G, Elongation factor Tu, Translation initiation factor IF2) of the Translation, Ribosomal Structure and Biogenesis functional category, one protein (DNA polymerase III, beta subunit) of the DNA Replication, Recombination and repair category, one protein (Preprotein translocase SecY) of the Cell Motility and Secretion category, and one protein (O-sialoglycoprotein endopeptidase) of the Posttranslational Modification, Protein Turnover, Chaperones category, as annotated in the Cluster of Orthologous Groups (COG) (Tatusov et al. 2001). After removal of multiple strains of the same species, GBlocks 0.91b (Castresana 2000) was applied to each protein in the concatenation to delete poorly aligned sites (i.e., sites with gaps in more than 50% of the species and conserved in less than 50% of the species) with the following parameters: minimum number of sequences for a conserved position: 110, minimum number of sequences for a flank position: 110, maximum number of contiguous non-conserved positions: 32000, allowed gap positions: with half. The signal-to-noise ratio was determined by altering the “minimum length of a block” parameter. -

Succession of Bacterial Communities in a Seasonally Stratified Lake with an Anoxic and Sulfidic Hypolimnion

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Succession of Bacterial Communities in a Seasonally Stratified Lake with an Anoxic and Sulfidic Hypolimnion Diao, M.; Sinnige, R. ; Kalbitz, K.; Huisman, J.; Muyzer, G. DOI 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02511 Publication date 2017 Document Version Final published version Published in Frontiers in Microbiology License CC BY Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Diao, M., Sinnige, R., Kalbitz, K., Huisman, J., & Muyzer, G. (2017). Succession of Bacterial Communities in a Seasonally Stratified Lake with an Anoxic and Sulfidic Hypolimnion. Frontiers in Microbiology, 8, [2511]. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02511 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam -

Phylogeny and Molecular Signatures (Conserved Proteins and Indels) That Are Specific for the Bacteroidetes and Chlorobi Species Radhey S Gupta* and Emily Lorenzini

BMC Evolutionary Biology BioMed Central Research article Open Access Phylogeny and molecular signatures (conserved proteins and indels) that are specific for the Bacteroidetes and Chlorobi species Radhey S Gupta* and Emily Lorenzini Address: Department of Biochemistry and Biomedical Science, McMaster University, Hamilton, L8N3Z5, Canada Email: Radhey S Gupta* - [email protected]; Emily Lorenzini - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 8 May 2007 Received: 21 December 2006 Accepted: 8 May 2007 BMC Evolutionary Biology 2007, 7:71 doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-71 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2148/7/71 © 2007 Gupta and Lorenzini; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Background: The Bacteroidetes and Chlorobi species constitute two main groups of the Bacteria that are closely related in phylogenetic trees. The Bacteroidetes species are widely distributed and include many important periodontal pathogens. In contrast, all Chlorobi are anoxygenic obligate photoautotrophs. Very few (or no) biochemical or molecular characteristics are known that are distinctive characteristics of these bacteria, or are commonly shared by them. Results: Systematic blast searches were performed on each open reading frame in the genomes of Porphyromonas gingivalis W83, Bacteroides fragilis YCH46, B. thetaiotaomicron VPI-5482, Gramella forsetii KT0803, Chlorobium luteolum (formerly Pelodictyon luteolum) DSM 273 and Chlorobaculum tepidum (formerly Chlorobium tepidum) TLS to search for proteins that are uniquely present in either all or certain subgroups of Bacteroidetes and Chlorobi. -

Archaea;Crenarchaeota;Marine;Other;Other Archaea;Crenarchaeota;Miscellaneous;Other;Other Archaea;Crenarchaeota;Soil;Other;Other

Archaea;Crenarchaeota;Marine;Other;Other Archaea;Crenarchaeota;Miscellaneous;Other;Other Archaea;Crenarchaeota;Soil;Other;Other Archaea;Crenarchaeota;South;Other;Other Archaea;Crenarchaeota;terrestrial;Other;Other Archaea;Euryarchaeota;Halobacteria;Halobacteriales;Miscellaneous Archaea;Euryarchaeota;Methanobacteria;Methanobacteriales;Methanobacteriaceae Archaea;Euryarchaeota;Methanomicrobia;Methanocellales;Methanocellaceae Archaea;Euryarchaeota;Methanomicrobia;Methanosarcinales;Methanosarcinaceae Archaea;Euryarchaeota;Thermoplasmata;Thermoplasmatales;Marine Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria;11-24;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteriales;Acidobacteriaceae Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria;BPC102;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria;Bryobacter;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria;Candidatus;Other Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria;DA023;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria;DA023;unidentified Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria;DS-100;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria;PAUC26f;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Acidobacteria;RB41;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Holophagae;32-20;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Holophagae;43F-1404R;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Holophagae;Holophagales;Holophagaceae Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Holophagae;NS72;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Holophagae;SJA-36;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Holophagae;Sva0725;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;Holophagae;iii1-8;uncultured Bacteria;Acidobacteria;RB25;uncultured;Other Bacteria;Actinobacteria;Actinobacteria;Actinobacteridae;Actinomycetales -

Systema Naturae. the Classification of Living Organisms

Systema Naturae. The classification of living organisms. c Alexey B. Shipunov v. 5.601 (June 26, 2007) Preface Most of researches agree that kingdom-level classification of living things needs the special rules and principles. Two approaches are possible: (a) tree- based, Hennigian approach will look for main dichotomies inside so-called “Tree of Life”; and (b) space-based, Linnaean approach will look for the key differences inside “Natural System” multidimensional “cloud”. Despite of clear advantages of tree-like approach (easy to develop rules and algorithms; trees are self-explaining), in many cases the space-based approach is still prefer- able, because it let us to summarize any kinds of taxonomically related da- ta and to compare different classifications quite easily. This approach also lead us to four-kingdom classification, but with different groups: Monera, Protista, Vegetabilia and Animalia, which represent different steps of in- creased complexity of living things, from simple prokaryotic cell to compound Nature Precedings : doi:10.1038/npre.2007.241.2 Posted 16 Aug 2007 eukaryotic cell and further to tissue/organ cell systems. The classification Only recent taxa. Viruses are not included. Abbreviations: incertae sedis (i.s.); pro parte (p.p.); sensu lato (s.l.); sedis mutabilis (sed.m.); sedis possi- bilis (sed.poss.); sensu stricto (s.str.); status mutabilis (stat.m.); quotes for “environmental” groups; asterisk for paraphyletic* taxa. 1 Regnum Monera Superphylum Archebacteria Phylum 1. Archebacteria Classis 1(1). Euryarcheota 1 2(2). Nanoarchaeota 3(3). Crenarchaeota 2 Superphylum Bacteria 3 Phylum 2. Firmicutes 4 Classis 1(4). Thermotogae sed.m. 2(5). -

Mean and SD Archaea Bacteria Genome Size (Mb)

Distributions for kingdom level Primer score mean and SD Genomic GC (%) mean and SD 60 3 2 50 1 Primer score 40 0 Genomic GC (%) Bacteria Bacteria Archaea Archaea kingdom kingdom 16S GC (%) mean and SD Genome size (Mb) mean and SD 65 5 60 4 55 3 16S GC (%) 2 Genome size (Mb) Genome size 50 Bacteria Bacteria Archaea Archaea kingdom kingdom 16S GC (%) Primer score 45 50 55 60 65 0 1 2 3 4 Acidobacteria Acidobacteria Actinobacteria Actinobacteria Aquificae Aquificae Bacteroidetes Bacteroidetes Caldiserica Caldiserica Chlamydiae Chlamydiae Chlorobi Primer scoremeanandSD Chlorobi 16S GC(%)meanandSD Chloroflexi Chloroflexi Chrysiogenetes Chrysiogenetes Crenarchaeota Crenarchaeota Cyanobacteria Cyanobacteria Deferribacteres Deferribacteres Deinococcus−Thermus Deinococcus−Thermus Dictyoglomi Dictyoglomi Elusimicrobia Elusimicrobia phylum phylum Euryarchaeota Euryarchaeota Fibrobacteres Fibrobacteres Firmicutes Firmicutes Fusobacteria Fusobacteria Gemmatimonadetes Gemmatimonadetes Ignavibacteria Ignavibacteria Ignavibacteriae Ignavibacteriae Korarchaeota Korarchaeota Lentisphaerae Lentisphaerae Nanoarchaeota Nanoarchaeota Nitrospirae Nitrospirae Planctomycetes Planctomycetes level phylum for Distributions Proteobacteria Proteobacteria Spirochaetes Spirochaetes Synergistetes Synergistetes Tenericutes Tenericutes Thaumarchaeota Thaumarchaeota Thermodesulfobacteria Thermodesulfobacteria Thermotogae Thermotogae unclassified unclassified Verrucomicrobia Verrucomicrobia Genome size (Mb) Genomic GC (%) 10.0 30 40 50 60 70 2.5 5.0 7.5 Acidobacteria Acidobacteria