An Ethnobotanical Study of Plant Use in Mêdog County, South-East Tibet, China Shan Li1,2*, Yu Zhang1, Yongjie Guo3,4, Lixin Yang1 and Yuhua Wang1*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report

Darwin Initiative Annual Report 1. Darwin Project Information Project Ref. Number 14-013 Project Title Community Management of NTFPs in Kangchenjunga Conservation Area, Nepal Country(ies) Nepal UK Contractor WWF UK Partner Organisation(s) WWF Nepal Program Darwin Grant Value GBP 170,100 Start/End dates April 2005-March 2008 Reporting period and 1 April 2005-31 March 2006 annual report number Annual report 1 Project website Author(s), date Suresh K. Ghimire, Bal Krishna Nepal, Parag Bijukchhe, Yeshi Lama, Jennifer Headley & Ros Coles 23 May 2006 2. Project Background • Briefly describe the location and circumstances of the project and the problem that the project aims to address. Situated in the remote, north-east corner of Nepal, bordering Sikkim (India) and Tibet Autonomous Region (China), Kangchenjunga Conservation Area (KCA) is characterized by great variations in elevation, climate, landscape, habitat, vegetation, and cultural diversity. Phyto-geographically, it forms the meeting ground of the Indo- Malaysian (S.E. Asian) and Sino-Japanese (E. Asian) floras. KCA has been declared as a “Gift to the Earth” in 1997. In 1998, WWF initiated the Kangchenjunga Conservation Area Project (KCAP) to conserve its rich biodiversity and promote community-based management of natural resources. About 1500 species of flowering plants have been documented thus far in KCA (Shrestha and Ghimire 1996), including over 150 species of non-timber forest products (Shrestha and Ghimire 1996; Sherpa 2001, Oli and Nepal 2003). NTFPs play an important role in supporting the livelihood of about 5000 people living in the four village development committees (VDCs) of Lelep, Tapethok, Yamphudin, and Walangchung Gola. -

Sendtnera 7: 163-201

© Biodiversity Heritage Library, http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/; www.biologiezentrum.at 163 Contributions to the knowledge of the genus Astragalus L. (Leguminosae) VII-X' D. PODLECH Abstract: PODLECH, D.: Contributions to the knowledge of the genus Astragalus L. (Legumi- nosae) VII-X. - Sendtnera 7: 163-201. 2001. ISSN 0944-0178. VII. A survey of Astragalus L. sect. Leucocercis. The section, endemic in Iran with six species, is revised. Synonymy, descriptions, the investigated specimens and a key for the species are given. VIII. New typifications and changes of typification in Astragalus-s^QcxQS. 12 wrongly typified species are re-typified. 19 taxa are typified here. IX. Some new species in genus Astragalus: 27 new species, one subspecies and one section are described here. They belong to the following sections: Sect. Caprini: A. behbehanensis, A. bozakmanii, A. spitzenbergeri. Sect. Cenantrum: A. tecti-mundi subsp. orientalis. Sect. Chlorostachys: A. poluninii, A. rhododendrophila. Sect. Cystium: A. owirensis. Sect. Dissitiflori: A. argentocalyx, A. bingoellensis, A. doabensis, A. fruticulosus, A. lanzhouensis, A. montis-karkasii, A. pravitzii, A. recurvatus, A. saadatabadensis, A. sata-kandaoensis , A. wakha- nicus. Sect. Hemiphaca: A. sherriffii, A. tsangpoensis. Sect. Incani: A. olurensis, A. zaraensis. Sect. Komaroviella: A. damxungensis. Sect. Onobrychoidei: A. ras- montii. Sect. Polycladus: A. austrotibetanus, A. cobresiiphila, A. conaensis. Sect. Pseudotapinodes, sect, nov.: A. dickorei. X. New names and combinations are given. Four illegitimate names are changed, two taxa have been raised in rank. Zusammenfassung: VII. A survey of Astragalus L. sect. Leucocercis. Eine Revision von Astragalus L. sect. Leucocercis wird vorgestellt. Die Sektion ist endemisch im Iran und umfasst sechs Arten. -

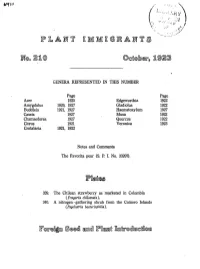

GENERA REPRESENTED in THIS NUMBER Acer Amygdalus

GENERA REPRESENTED IN THIS NUMBER Page Page Acer 1925 Edgeworthia 1922 Amygdalus 1926, 1927 Gladiolus 1922 Buddleia 1921, 1927 Haematoxylum 1927 Cassia 1927 Musa 1922 Chamaedorea 1927 Quercus 1922 Citrus 1921 Veronica 1923 Crotalaria 1921, 1922 Notes and Comments The Favorita pear (S. P. I. No. 33207). 339. The Chilean strawberry as marketed in Colombia (Fragaria chiloensis). 340. A nitrogen * gathering shrub from the Comoro Islands {Psychotria bacteriophila). EXPLANATORY NOTE PLANT IMMIGRANTS is designed principally to call the attention of plant breeders and experimenters to the arrival of interesting plant material. It should not be viewed as an announcement of plants available for distribution, since most introductions have to be propagated before they can be sent to experimenters. This requires from one to three years, depending upon the nature of the plant and the quantity of live material received. As rapidly as stocks are available, the plants described in this circular will be included in the Annual List of Plant Introductions, which is sent to experimenters in late autumn. Introductions made for a special purpose (as for example to supply Department and other specialists with material needed in their experiments) are not propagated by this Office and will not appear in the Annual List. Descriptions appearing here are revised and later published in the Inventory of Seed,s and Plants Imported, -the permanent record of plant in- troductions made by this Office. Plant breeders and experimenters who desire plants not available in this country are invited to correspond with this Office which will endeavor to secure the required material through its agricultural ex- plorers, foreign collaborators, or correspondents. -

Plant Science Today (2017) 4(1): 1-11 1

Plant Science Today (2017) 4(1): 1-11 1 http://dx.doi.org/10.14719/pst.2017.4.1.268 ISSN: 2348-1900 Plant Science Today http://horizonepublishing.com/journals/index.php/PST Research Article Ethnobotanical plants of Veligonda Hills, Southern Eastern Ghats, Andhra Pradesh, India S K M Basha1* and P Siva Kumar Reddy2 1NBKR Medicinal Plant Research Institute, Vidya Nagar, SPSR Nellore, Andhra Pradesh, India 2Research and Development Centre, Bharathiyar University, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India Article history Abstract Received: 04 September 2016 The Veligonda range which separates the Nellore district from Kadapa and Kurnool is Accepted: 16 October 2016 the back bone of the Eastern Ghats, starting from Nagari promontory in Chittoor Published: 01 January 2017 district. It runs in a northerly direction along the western boarders of the Nellore © Basha & Siva Kumar Reddy (2017) district, raising elevation of 3,626 feet at Penchalakona in Rapur thaluk. Veligonda hill ranges have high alttudinal and deep valley. These hills have rich biodiversity and Editor many rare, endangered, endemic and threatned plants are habituated in these hills. K. K. Sabu The present paper mainly deals with the ethanobotanical plants used by local people. Publisher Keywords Horizon e-Publishing Group Ethnobotany; Threatened; Endangered; Endemic; Veligonda hill range Corresponding Author S K M Basha Basha, S. K. M., and P. Siva Kumar Reddy. 2017. Ethnobotanical plants of Veligonda Hills, Southern Eastern Ghats, Andhra Pradesh, India. Plant Science Today 4(1): 1-11. [email protected] http://dx.doi.org/10.14719/pst.2017.4.1.268 Introduction communities in every ecosystem from the Trans The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated Himalayas down to the coastal plains have that 80% of the population of developing countries discovered the medical uses of thousands of plants relies on traditional medicines, mostly plant drugs, found locally in their ecosystem. -

Testing Darwin's Transoceanic Dispersal Hypothesis for the Inland

Aberystwyth University Testing Darwin’s transoceanic dispersal hypothesis for the inland nettle family (Urticaceae) Wu, ZengYuan; Liu, Jie; Provan, James; Wang, Hong; Chen, Chia-Jui; Cadotte, Marc; Luo, Ya-Huang; Amorim, Bruno; Li, De-Zhu; Milne, Richard Published in: Ecology Letters DOI: 10.1111/ele.13132 Publication date: 2018 Citation for published version (APA): Wu, Z., Liu, J., Provan, J., Wang, H., Chen, C-J., Cadotte, M., Luo, Y-H., Amorim, B., Li, D-Z., & Milne, R. (2018). Testing Darwin’s transoceanic dispersal hypothesis for the inland nettle family (Urticaceae). Ecology Letters, 21(10), 1515-1529. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13132 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Aberystwyth Research Portal (the Institutional Repository) are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Aberystwyth Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Aberystwyth Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. tel: +44 1970 62 2400 email: [email protected] Download date: 27. Sep. 2021 Testing Darwin’s transoceanic dispersal hypothesis for the inland nettle family (Urticaceae) Zeng-Yuan Wu1, Jie Liu2, Jim Provan3, Hong Wang2, Chia-Jui Chen5, Marc W. -

Ethnobotanical Study on Wild Edible Plants Used by Three Trans-Boundary Ethnic Groups in Jiangcheng County, Pu’Er, Southwest China

Ethnobotanical study on wild edible plants used by three trans-boundary ethnic groups in Jiangcheng County, Pu’er, Southwest China Yilin Cao Agriculture Service Center, Zhengdong Township, Pu'er City, Yunnan China ren li ( [email protected] ) Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0810-0359 Shishun Zhou Shoutheast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences & Center for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences Liang Song Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences & Center for Intergrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences Ruichang Quan Southeast Asia Biodiversity Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Sciences & Center for Integrative Conservation, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences Huabin Hu CAS Key Laboratory of Tropical Plant Resources and Sustainable Use, Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences Research Keywords: wild edible plants, trans-boundary ethnic groups, traditional knowledge, conservation and sustainable use, Jiangcheng County Posted Date: September 29th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-40805/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on October 27th, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-020-00420-1. Page 1/35 Abstract Background: Dai, Hani, and Yao people, in the trans-boundary region between China, Laos, and Vietnam, have gathered plentiful traditional knowledge about wild edible plants during their long history of understanding and using natural resources. The ecologically rich environment and the multi-ethnic integration provide a valuable foundation and driving force for high biodiversity and cultural diversity in this region. -

Field Report on the Preliminary Feasibility Study

Field report on the Preliminary Feasibility Study On Walking Trees along Lifezone Ecotones in Barun Valley, Nepal (A pilot project to develop key indicators for monitoring Biomeridians - Climate Response through Information & Local Engagement) Report Prepared By: The East Foundation (TEF), Sankhuwasabha, Nepal and Future Generations University, Franklin, WV, USA Submitted to Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation Babar Mahal, Kathmandu June 2018 1 Table of Contents Contents Page No. 1. Background ........................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Rationale ............................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Study Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 6 3.1 Contextual Framework ...................................................................................................................... 7 3.2 Study Area Description ..................................................................................................................... 9 3.3 Experimental Design and Data Collection Methodology ............................................................... 12 4. Study Findings .................................................................................................................................... 13 4.1 Geographic Summary -

For Enumeration of This Part a Linear Sequence of Lycophytes and Ferns After Christenhusz, M

PTERIDOPHYTA For enumeration of this part A linear sequence of Lycophytes and Ferns after Christenhusz, M. J. M.; Zhang, X.C. & Schneider, H. (2011) has been followed Subclass: Lycopodiidae Beketov (1863). Order: Selaginellales (1874). Selaginellaceae Willkomm, Anleit. Stud. Bot. 2: 163. 1854; Prodr. FI. Hisp. 1(1): 14. 1861. SELAGINELLA P. Beauvois, Megasin Encycl. 9: 478. 1804. Selaginella monospora Spring, Mém. Acad. Roy. Sci. Belgique 24: 135. 1850; Monogr. Lyc. II:135. 1850; Alston, Bull. Fan. Mem. Inst. Biol. Bot. 5: 288, 1954; Alston, Proc. Nat. Inst. Sc. Ind. 11: 228. 1945; Reed, C.F., Ind. Sellaginellarum 160 – 161. 1966; Panigrahi et Dixit, Proc. Nat. Inst. Sc. Ind. 34B (4): 201, f.6. 1968; Kunio Iwatsuki in Hara, Fl. East. Himal. 3: 168. 1972; Ghosh et al., Pter. Fl. East. Ind. 1: 127. 2004. Selaginella gorvalensis Spring, Monogr. Lyc. II: 256. 1850; Bak, Handb. Fern Allies 107. 1887; Selaginella microclada Bak, Jour. Bot. 22: 246. 1884; Selaginella plumose var. monospora (Spring) Bak, Jour. Bot. 21:145. 1883; Selaginella semicordata sensu Burkill, Rec. Bot. Surv. Ind. 10: 228. 1925, non Spring. Plant up to 90 cm, main stem prostrate, rooting on all sides and at intervals, unequally tetragonal, main stem alternately branched 5 – 9 times, branching unequal, flexuous; leavesobscurely green, dimorphus, lateral leaves oblong to ovate-lanceolate, subacute, denticulate to serrulate at base. Spike short, quadrangular, sporophylls dimorphic, large sporophyls less than half as long as lateral leaves, oblong- lanceolate, obtuse, denticulate, small sporophylls dentate, ovate, acuminate. Fertile: October to January. Specimen Cited: Park, Rajib & AP Das 0521, dated 23. 07. -

The 132 Ma Comei-Bunbury Large Igneous Province: Remnants Identifi Ed in Present-Day Southeastern Tibet and Southwestern Australia

The 132 Ma Comei-Bunbury large igneous province: Remnants identifi ed in present-day southeastern Tibet and southwestern Australia Di-Cheng Zhu1*, Sun-Lin Chung2, Xuan-Xue Mo1*, Zhi-Dan Zhao1, Yaoling Niu3, Biao Song4, and Yue-Heng Yang5 1State Key Laboratory of Geological Processes and Mineral Resources, China University of Geosciences, Beijing 100083, China 2Department of Geosciences, National Taiwan University, Taipei 106, Taiwan 3Department of Earth Sciences, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, UK 4Beijing SHRIMP II Center, Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, Beijing 100037, China 5Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China ABSTRACT and Cona areas; Fig. 1B) of southern Tibet. The We report 11 new U-Pb zircon ages obtained by sensitive high-resolution ion microprobe new data obtained in this study together with (SHRIMP) and laser ablation–inductively coupled plasma–mass spectrometry (LA-ICP–MS) fi eld observations and consideration in a global for a large province of Early Cretaceous Comei igneous rocks consisting of basaltic lavas, context further suggest that the rocks in south- mafi c sills and dikes, and gabbroic intrusions together with subordinate layered ultramafi c eastern Tibet and the Bunbury Basalt in south- intrusions and silicic volcanic rocks exposed in the Tethyan Himalaya, southeastern Tibet. western Australia are temporally related and Available zircon U-Pb ages obtained from various rocks in this province, which has an areal constitute the erosional and/or deformational extent of ~40,000 km2 (~270 km × 150 km), indicate that the magmatism occurred ca. 132 Ma remnants of a large igneous province, which ago, coeval with the Bunbury Basalt in southwestern Australia. -

The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India

THE AYURVEDIC PHARMACOPOEIA OF INDIA PART- I VOLUME – V GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT OF AYUSH Contents | Monographs | Abbreviations | Appendices Legal Notices | General Notices Note: This e-Book contains Computer Database generated Monographs which are reproduced from official publication. The order of contents under the sections of Synonyms, Rasa, Guna, Virya, Vipaka, Karma, Formulations, Therapeutic uses may be shuffled, but the contents are same from the original source. However, in case of doubt, the user is advised to refer the official book. i CONTENTS Legal Notices General Notices MONOGRAPHS Page S.No Plant Name Botanical Name No. (as per book) 1 ËMRA HARIDRË (Rhizome) Curcuma amada Roxb. 1 2 ANISÍNA (Fruit) Pimpinella anisum Linn 3 3 A×KOLAH(Leaf) Alangium salviifolium (Linn.f.) Wang 5 4 ËRAGVËDHA(Stem bark) Cassia fistula Linn 8 5 ËSPHOÙË (Root) Vallaris Solanacea Kuntze 10 6 BASTËNTRÌ(Root) Argyreia nervosa (Burm.f.)Boj. 12 7 BHURJAH (Stem Bark) Betula utilis D.Don 14 8 CAÛÚË (Root) Angelica Archangelica Linn. 16 9 CORAKAH (Root Sock) Angelica glauca Edgw. 18 10 DARBHA (Root) Imperata cylindrica (Linn) Beauv. 21 11 DHANVAYËSAH (Whole Plant) Fagonia cretica Linn. 23 12 DRAVANTÌ(Seed) Jatropha glandulifera Roxb. 26 13 DUGDHIKË (Whole Plant) Euphorbia prostrata W.Ait 28 14 ELAVËLUKAê (Seed) Prunus avium Linn.f. 31 15 GAÛÚÌRA (Root) Coleus forskohlii Briq. 33 16 GAVEDHUKA (Root) Coix lachryma-jobi LInn 35 17 GHOÛÙË (Fruit) Ziziphus xylopyrus Willd. 37 18 GUNDRËH (Rhizome and Fruit) Typha australis -

Asia Regional Synthesis for the State of the World?

REGIONAL SYNTHESIS REPORTS ASIA REGIONAL SYNTHESIS FOR THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S BIODIVERSITY FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ASIA REGIONAL SYNTHESIS FOR THE STATE OF THE WORLD’S BIODIVERSITY FOR FOOD AND AGRICULTURE FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS ROME, 2019 Required citation: FAO. 2019. Asia Regional Synthesis for The State of the World’s Biodiversity for Food and Agriculture. Rome. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. ISBN 978-92-5-132041-9 © FAO, 2019 Some rights reserved. This work is made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/ legalcode/legalcode). Under the terms of this licence, this work may be copied, redistributed and adapted for non-commercial purposes, provided that the work is appropriately cited. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that FAO endorses any specific organization, products or services. -

The Ayurvedic Pharmacopoeia of India

THE AYURVEDIC PHARMACOPOEIA OF INDIA PART- I VOLUME – V GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND FAMILY WELFARE DEPARTMENT OF AYUSH Contents | Monographs | Abbreviations | Appendices Legal Notices | General Notices i CONTENTS Legal Notices General Notices MONOGRAPHS Page S.No Plant Name Botanical Name No. (as per book) 1 ËMRA HARIDRË (Rhizome) Curcuma amada Roxb. 1 2 ANISÍNA (Fruit) Pimpinella anisum Linn 3 3 A×KOLAé (Leaf) Alangium salviifolium (Linn.f.) Wang 5 4 ËRAGVËDHA (Stem bark) Cassia fistula Linn 8 5 ËSPHOÙË (Root) Vallaris Solanacea Kuntze 10 6 BASTËNTRÌ (Root) Argyreia nervosa (Burm.f.)Boj. 12 7 BHÍRJAé (Stem Bark) Betula utilis D.Don 14 8 CAÛÚË (Root) Angelica Archangelica Linn. 16 9 CORAKAé (Root Sock) Angelica glauca Edgw. 18 10 DARBHA (Root) Imperata cylindrica (Linn) Beauv. 21 11 DHANVAYËSAé (Whole Plant) Fagonia cretica Linn. 23 12 DRAVANTÌ (Seed) Jatropha glandulifera Roxb. 26 13 DUGDHIKË (Whole Plant) Euphorbia prostrata W.Ait 28 14 ELAVËLUKAê (Seed) Prunus avium Linn.f. 31 15 GAÛÚÌRA (Root) Coleus forskohlii Briq. 33 16 GAVEDHUKA (Root) Coix lachryma-jobi LInn 35 17 GHOÛÙË (Fruit) Ziziphus xylopyrus Willd. 37 18 GUNDRËé (Rhizome and Fruit) Typha australis Schum. and Thonn. 39 19 HIêSRË(Root) Capparis spinosa Linn. 41 20 HI×GUPATRÌ (Leaf) Ferula jaeschkeana Vatke 43 21 ITKAÙA (Root) Sesbania bispinosa W.F.Wight 45 22 ITKAÙA(Stem) Sesbania bispinosa W.F.Wight 47 23 JALAPIPPALÌ (Whole Plant) Phyla nodiflora Greene 49 ii 24 JÌVAKAé (Pseudo Bulb) Malaxis acuminata D.Don 52 25 KADARAé (Heart Wood) Acacia suma (Buch-Ham)