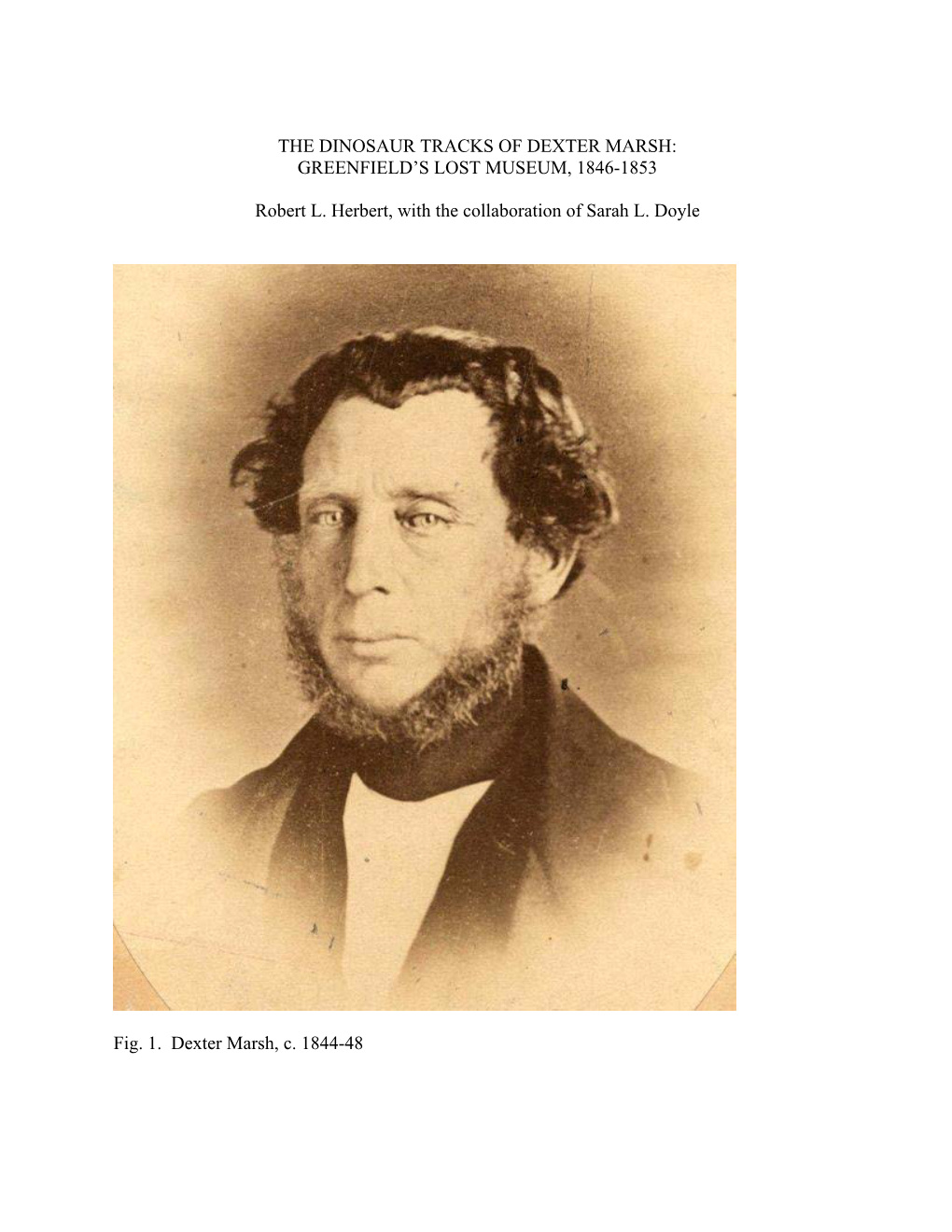

Dexter Marsh: Greenfield’S Lost Museum, 1846-1853

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Early Jurassic Ornithischian Dinosaurian Ichnogenus Anomoepus

19 The Early Jurassic Ornithischian Dinosaurian Ichnogenus Anomoepus Paul E. Olsen and Emma C. Rainforth nomoepus is an Early Jurassic footprint genus and 19.2). Because skeletons of dinosaur feet were not produced by a relatively small, gracile orni- known at the time, he naturally attributed the foot- A thischian dinosaur. It has a pentadactyl ma- prints to birds. By 1848, however, he recognized that nus and a tetradactyl pes, but only three pedal digits some of the birdlike tracks were associated with im- normally impressed while the animal was walking. The pressions of five-fingered manus, and he gave the name ichnogenus is diagnosed by having the metatarsal- Anomoepus, meaning “unlike foot,” to these birdlike phalangeal pad of digit IV of the pes lying nearly in line with the axis of pedal digit III in walking traces, in combination with a pentadactyl manus. It has a pro- portionally shorter digit III than grallatorid (theropod) tracks, but based on osteometric analysis, Anomoepus, like grallatorids, shows a relatively shorter digit III in larger specimens. Anomoepus is characteristically bi- pedal, but there are quadrupedal trackways and less common sitting traces. The ichnogenus is known from eastern and western North America, Europe, and southern Africa. On the basis of a detailed review of classic and new material, we recognize only the type ichnospecies Anomoepus scambus within eastern North America. Anomoepus is known from many hundreds of specimens, some with remarkable preservation, showing many hitherto unrecognized details of squa- mation and behavior. . Pangea at approximately 200 Ma, showing the In 1836, Edward Hitchcock described the first of what areas producing Anomoepus discussed in this chapter: 1, Newark we now recognize as dinosaur tracks from Early Juras- Supergroup, eastern North America; 2, Karoo basin; 3, Poland; sic Newark Supergroup rift strata of the Connecticut 4, Colorado Plateau. -

General Index Vols. XLI-L, Third Series

GENERAL INDEX OF VOLUMES XLI-L OF THE THIRD SERIES. WInthe references to volumes xli to I, only the numerals i to ir we given. NOTE.-The names of mineral8 nre inaerted under the head ol' ~~IBERALB:all ohitllary notices are referred to under OBITUARY. Under the heads BO'PANY,CHK~I~TRY, OEOLO~Y, Roo~s,the refereuces to the topics in these department8 are grouped together; in many cases, the same references appear also elsewhere. Alabama, geological survey, see GEOL. REPORTSand SURVEYS. Abbe, C., atmospheric radiation of Industrial and Scientific Society, heat, iii, 364 ; RIechnnics of the i. 267. Earth's Atmosphere, v, 442. Alnska, expedition to, Russell, ii, 171. Aberration, Rayleigh, iii, 432. Albirnpean studies, Uhler, iv, 333. Absorption by alum, Hutchins, iii, Alps, section of, Rothpletz, vii, 482. 526--. Alternating currents. Bedell and Cre- Absorption fipectra, Julius, v, 254. hore, v, 435 ; reronance analysis, ilcadeiny of Sciences, French, ix, 328. Pupin, viii, 379, 473. academy, National, meeting at Al- Altitudes in the United States, dic- bany, vi, 483: Baltimore, iv, ,504 : tionary of, Gannett, iv. 262. New Haven, viii, 513 ; New York, Alum crystals, anomalies in the ii. 523: Washington, i, 521, iii, growth, JIiers, viii, 350. 441, v, 527, vii, 484, ix, 428. Aluminum, Tvave length of ultra-violet on electrical measurements, ix, lines of, Runge, 1, 71. 236, 316. American Association of Chemists, i, Texas, Transactions, v, 78. 927 . Acoustics, rrsearchesin, RIayer, vii, 1. Geological Society, see GEOL. Acton, E. H., Practical physiology of SOCIETYof AMERICA. plants, ix, 77. Nuseu~nof Sat. Hist., bulletin, Adams, F. -

The New Ichnotaxon Eubrontes Nobitai Ichnosp. Nov. and Other

Xing et al. Journal of Palaeogeography (2021) 10:17 https://doi.org/10.1186/s42501-021-00096-y Journal of Palaeogeography ORIGINAL ARTICLE Open Access The new ichnotaxon Eubrontes nobitai ichnosp. nov. and other saurischian tracks from the Lower Cretaceous of Sichuan Province and a review of Chinese Eubrontes-type tracks Li-Da Xing1,2* , Martin G. Lockley3, Hendrik Klein4, Li-Jun Zhang5, Anthony Romilio6, W. Scott Persons IV7, Guang-Zhao Peng8, Yong Ye8 and Miao-Yan Wang2 Abstract The Jiaguan Formation and the underlying Feitianshan Formation (Lower Cretaceous) in Sichuan Province yield multiple saurischian (theropod–sauropod) dominated ichnofaunas. To date, a moderate diversity of six theropod ichnogenera has been reported, but none of these have been identified at the ichnospecies level. Thus, many morphotypes have common “generic” labels such as Grallator, Eubrontes, cf. Eubrontes or even “Eubrontes- Megalosauripus” morphotype. These morphotypes are generally more typical of the Jurassic, whereas other more distinctive theropod tracks (Minisauripus and Velociraptorichnus) are restricted to the Cretaceous. The new ichnospecies Eubrontes nobitai ichnosp nov. is distinguished from Jurassic morphotypes based on a very well- preserved trackway and represents the first-named Eubrontes ichnospecies from the Cretaceous of Asia. Keywords: Ichnofossils, Dinosaur footprints, Theropod, Myths 1 Introduction are represented by Brontopodus-type tracks. The non- With over 17 track sites documented so far, the Jiaguan avian theropod tracks consist of Eubrontes-type, gralla- Formation and the underlying Feitianshan Formation torid, Yangtzepus, Velociraptorichnus, cf. Dromaeopodus, hold among the richest records of dinosaur tracks in Minisauripus, cf. Irenesauripus, and Gigandipus, while China (Young 1960; Xing and Lockley 2016; Xing et al. -

Experimental Study of Sediment Type and Organic Content on Fossil Trackway Preservation

EXPERIMENTAL STUDY OF SEDIMENT TYPE AND ORGANIC CONTENT ON FOSSIL TRACKWAY PRESERVATION Undergraduate Research Thesis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with research distinction in Earth Sciences in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University By Nicholas P. Reineck The Ohio State University 2019 Approved by Loren E. Babcock, Advisor School of Earth Sciences ii T ABLE OF C ONTENTS Abstract………………………………………………………………………….ii Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………..iii List of Figures……………………………………………………………………iv Introduction………………………………………………………………………1 Methods……..……………………...………………………...…………………..2 Results……………………………………………………………………………5 Discussion……………………………………………………………………….11 Conclusions……………………………………………………………………...13 Recommendations for Future Research…………………………………………14 References Cited….……….…………………………………………………….15 i ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to determine the effects of different sediment types on the preservation of footprints prior to fossilization. The sediments collected were an organic-poor sand, an organic-rich sand, an organic-poor clay, and an organic-rich clay. These sediments were chosen to mimic ephemerally wet siliciclastic environments similar to those of the Connecticut River Valley deposit (Newark Supergroup, Lower Jurassic). A pair of chicken feet was used to mimic the feet of a small theropod dinosaur. The sediments were separated into containers and allowed to sit to see if any significant microbial growth would develop within the sediments. Then chicken feet were used to create prints in the damp sediment. The footprints were repeatedly hydrated and desiccated until barely or no longer visible. Based on observations made of the footprints in varied sediment types, the clays were found to be better than sands at preserving the shapes of footprints over long periods of time and repeated wet-dry cycles. Organic-rich sediments were better than organic-poor sediments at preserving the footprints. -

Interpreting Behavior from Early Cretaceous Bird Tracks and the Morphology of Bird Feet and Trackways

INTERPRETING BEHAVIOR FROM EARLY CRETACEOUS BIRD TRACKS AND THE MORPHOLOGY OF BIRD FEET AND TRACKWAYS By ©2009 Amanda Renee Falk B.S., Lake Superior State University, 2007 Submitted to the Department of Geology and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Advisory Committee: ______________________________ Co-Chairman: Stephen T. Hasiotis ______________________________ Co-Chairman: Larry D. Martin ______________________________ J. F. Devlin Date Defended: September 15th, 2009 The thesis committee for Amanda R. Falk certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: INTERPRETING BEHAVIOR FROM EARLY CRETACEOUS BIRD TRACKS AND THE MORPHOLOGY OF BIRD FEET AND TRACKWAYS Advisory Committee: ____________________________ Stephen T. Hasiotis, Chairman ____________________________ Larry D. Martin, Co-Chairman ____________________________ J. F. Devlin Date approved: _ September 15th, 2009_ ii ABSTRACT Amanda R. Falk Department of Geology, September 2009 University of Kansas Bird tracks were studied from the Lower Cretaceous Lakota Formation in South Dakota, USA, and the Lower Cretaceous Haman Formation, South Korea. Behaviors documented from the Lakota Formation included: (1) a takeoff behavior represented by a trackway terminating in two subparallel tracks; (2) circular walking; and (3) the courtship display high stepping. Behaviors documented from the Haman Formation included: (1) a low-angle landing in which the hallux toe was dragged; (2) pecking and probing behaviors; and (3) flapping-assisted hopping during walking. The invertebrate trace fossil Cochlichnus was associated the avian tracks from the Lakota Formation. No traces of pecking or probing were associated with Cochlichnus. The invertebrate trace fossils Cochlichnus, Arenicholites, and Steinichnus were found associated the bird tracks from the Haman Formation. -

Dr. James Deane of Greenfield

DR. JAMES DEANE OF GREENFIELD EDWARD HITCHCOCK’S RIVAL DISCOVERER OF DINOSAUR TRACKS Robert L. Herbert, with the collaboration of Sarah Doyle and photography by Bill Finn and Ed Gregory Deane! 2 Contents List of illustrations 3 Preface and notes to the reader 5 Deane’s home, office, and library 7 Deane’s early life 13 Sandstone discoveries 1835-1841 18 Raising Silkworms, 1839-1842 23 The Deane-Hitchcock rivalry, 1841-1844 27 Deane’s medical career 1841-1851 33 More rivalry with Hitchcock, 1845-1849 35 Deane’s medical associations 41 Deane’s secular life: Masonry and anti-slavery 44 No more bird tracks? 46 Hitchcock’s Ichnology of New England, 1858 52 Deane’s posthumous Iconographs, 1861 56 Conclusion: Deane and Hitchcock 60 Bibliography 64 Deane! 3 List of illustrations Page 7, fig. 1. James Deane, daguerreotype, c. 1845-1850. Greenfield Historical Society, courtesy of Special Collections and Archives, Amherst College. Page 17, fig. 2. Map of Greenfield (French and Clark), 1855, detail. Courtesy of David Allen (www.old-maps.com). Page 18, fig. 3. James Deane’s house, Main St., in later years. Courtesy of Peter S. Smith. Page 20, fig. 4. Edward Hitchcock, c. 1860-1862. Photograph by Lovell, Amherst. Courtesy of Special Collections and Archives, Amherst College. Page 21, fig. 5. Proportional View of Ornithichnites, lithograph, American Journal of Science, April 1836, for article by Edward Hitchcock. 1836. Ed Gregory image. Page 21, fig. 6. Sandstone trackways, lithograph, American Journal of Science, April 1836, for article by Edward Hitchcock. Ed Gregory image. Page 22, fig. -

Tesi Dottorato.Indb

Table of contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 5 2. History of ichnology ........................................................................................................................9 2.1 A history of ideas in ichnology ............................................................................................11 3. Neoichnology ................................................................................................................................ 75 3.1 Neoichnology of a barrier-island system: the Mula di Muggia (Grado lagoon, Italy) ............................................................................................ 78 3.2 The IchnoGIS method: Network science and geostatistics in ichnology. Theory and application (Grado lagoon, Italy) .................................................................................... 124 3.3 Does the IchnoGIS method work? Prediction performance at the Mula di Muggia (Northern Adriatic, Italy) .......................................... 203 4. Palaeoichnology ......................................................................................................................... 251 4.1 Architectures of behavioural complexity: ichnonetwork analysis of the Meledis- Pizzul Formations (Upper Carboniferous; Pramollo, Italy-Austria) ................................................... 254 4.2 Behaviours mapped by new geographies: ichnonetwork -

Scientific Truth, Rightly Understood, Is Religious Truth”: the Life and Works of Reverend Edward Hitchcock, 1793-1864

ABSTRACT Title of thesis: “SCIENTIFIC TRUTH, RIGHTLY UNDERSTOOD, IS RELIGIOUS TRUTH”: THE LIFE AND WORKS OF REVEREND EDWARD HITCHCOCK, 1793-1864 Ariel Jacob Segal, Master of Arts, 2005 Thesis directed by: Professor James B. Gilbert Depart ment of History Reverend Edward Hitchcock (1793-1864) was an important figure in 19th century American science. He contributed to the fields of geology and paleontology, and was the founder of paleoichnology. The overriding passion of Hitchcock’s life was the reconciliation of science with evangelical Protestant Christianity. For most of his career, he located all of geological time in a “gap” between the first two verses of Genesis, but later tended to view the Creation days themselves as symbolic. Hitchcock also dealt intensively with the scientific understanding of Noah’s flood. At first, he advocated a Deluge covering the entire planet. Subsequently, he held that the Deluge only affected the portion of the planet inhabited by humanity during the time of Noah. Hitchcock used evidence from science to support both natural and revealed religion. He combined this synthesizing with an increasingly extravagant romanticism, and confidently looked forward to continuing his scientific investigations in Heav en. “SCIENTIFIC TRUTH, RIGHTLY UNDERSTOOD, IS RELIGIOUS TRUTH”: THE LIFE AND WORKS OF REVEREND EDWARD HITCHCOCK, 1793-1864 by Ariel Jacob Segal Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2005 Advisory Committee: Professor James B. Gilbert, Chair Professor Stephen G. Brush Dr. Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. ©Copyright by Ariel Jacob Segal 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to thank my thesis adviser, Dr. -

The Folklore of Dinosaur Trackways in China: Impact on Paleontology Lida Xing a , Adrienne Mayor B , Yu Chen C , Jerald D

This article was downloaded by: [Lida Xing] On: 12 December 2011, At: 10:37 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Ichnos Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gich20 The Folklore of Dinosaur Trackways in China: Impact on Paleontology Lida Xing a , Adrienne Mayor b , Yu Chen c , Jerald D. Harris d & Michael E. Burns a a Department of Biological Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada b Classics Department, Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA c Capital Museum, Beijing, China d Physical Sciences Department, Dixie State College, St. George, Utah, USA Available online: 12 Dec 2011 To cite this article: Lida Xing, Adrienne Mayor, Yu Chen, Jerald D. Harris & Michael E. Burns (2011): The Folklore of Dinosaur Trackways in China: Impact on Paleontology, Ichnos, 18:4, 213-220 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2011.634038 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. -

The Rocky Hill Dinosaurs

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository New England Intercollegiate Geological NEIGC Trips Excursion Collection 1-1-1968 The Rocky Hill Dinosaurs Ostrom, John H. Quarrier, Sidney S. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips Recommended Citation Ostrom, John H. and Quarrier, Sidney S., "The Rocky Hill Dinosaurs" (1968). NEIGC Trips. 96. https://scholars.unh.edu/neigc_trips/96 This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the New England Intercollegiate Geological Excursion Collection at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in NEIGC Trips by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. C-3 1 Trip C-3 THE ROCKY HILL DINOSAURS by John H. Ostrom Yale University with an Introduction by Sidney S. Quarrier Connecticut Geological and Natural History Survey INTRODUCTION On August 24, 1966, excavations were under way for the foundation of a Connecticut State Highway Department testing laboratory in the Town of Rocky Hill. Edward McCarthy, a bulldozer operator, noticed that his machine had uncovered a slab of rock bearing oddly shaped tracks; and, thinking that the tracks might hold some significance, he stopped his machine and called the attention of the engineer to his find. In a rapid succession of events, interested personnel were notified of the discovery; its scientific and educational values were determined; and with a speed rare in government circles, steps were immediately in stituted through the direct action of Governor John Dempsey to preserve the tracks in place. -

Published Works Cited

Works Cited in All the Light Here Comes from Above: the Life and Legacy of Edward Hitchcock by Robert T. McMaster Updated 11/3/2020 Published works include books, journal articles and newspaper articles. Unpublished works are listed separately. AC Amherst College Archives and Special Collections, Amherst, Mass. AJS American Journal of Science and Arts AMM American Monthly Magazine and Critical Review EMJH Edward (Jr.) and Mary Judson Hitchcock Family Papers, 1840-1962 at AC EOH Edward & Orra White Hitchcock Papers at AC HD Henry N. Flynt Library, Historic Deerfield, Deerfield, Mass. HFP Hitchcock Family Papers at PVMA NAR North American Review PVMA Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association, Deerfield, Mass. Published Works Cited “Academic Honours,” AMM 4 (November 1818), 65. Acts and Resolves Passed by the General Court of Massachusetts in the Year 1863. Boston, Mass.: Wright and Potter, 1863. Agassiz, Louis. “The Diversity of Origin of the Human Races.” Christian Examiner and Religious Miscellany 4th ser. 14 (July 1850): 110-145. [Agassiz, Louis], Review of Elementary Anatomy and Physiology, Boston (Mass.) Evening Courier, March 3, 1860, 1. “Agricultural College at Amherst,” Springfield (Mass.) Republican, June 4, 1864, 2. “American Association for the Advancement of Science,” Springfield (Mass.) Republican, August 8, 1859, 4. “Amherst College,” Hampshire and Franklin Express (Amherst, Mass.), April 18, 1845, 1. “Amherst College—Religion,” Southern Patriot (Charleston, SC), May 14, 1846, 2. “Anniversary at South Hadley,” Springfield (Mass.) Republican, July 22, 1864, 2. “Appointments by the Governor and Council,” Boston Courier, June 28, 1830, 1. Bakker, Robert T. “Dinosaur Renaissance.” Scientific American 232 (April 1975): 58-78. -

Etd-03222016-123912.Pdf (7.911 Mb )

Template B v3.0 (beta): Created by J. Nail 06/2015 Maximizing the informal education of Death Valley National Park ichnofossils By TITLE PAGE Curt Edward Burbach A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Mississippi State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Geoscience in the Department of Geoscience Mississippi State, Mississippi May 2016 Copyright by COPYRIGHT PAGE Curt Edward Burbach 2016 Maximizing the informal education of Death Valley National Park ichnofossils By APPROVAL PAGE Curt Edward Burbach Approved: ____________________________________ Renee M. Clary (Director of Thesis) ____________________________________ Darrel W. Schmitz (Committee Member) ____________________________________ Ryan M. Walker (Committee Member) ____________________________________ Michael E. Brown (Graduate Coordinator) ____________________________________ Rick Travis Interim Dean College of Arts & Sciences Name: Curt Edward Burbach ABSTRACT Date of Degree: May 7, 2016 Institution: Mississippi State University Major Field: Geoscience Director of Thesis: Renee M. Clary Title of Study: Maximizing the informal education of Death Valley National Park ichnofossils Pages in Study 345 Candidate for Degree of Master of Science Certain sites within Death Valley National Park contain ample ichnofossils, specifically vertebrate animal tracks, dating back to the Pliocene. Since the majority of these track locations are closed to the general public, their scientific significance and educational value toward improving the geoliteracy of the general public remain unexplored. Based on the impressive amount of ichnofossils present at the park, this research investigates how to improve general public geoliteracy through these tracks, using basic principles and supporting concepts of the National Science Foundation’s Earth Science Literacy Initiative, while respecting the security measures of the park and adhering to National Park Service interpretation guidelines.