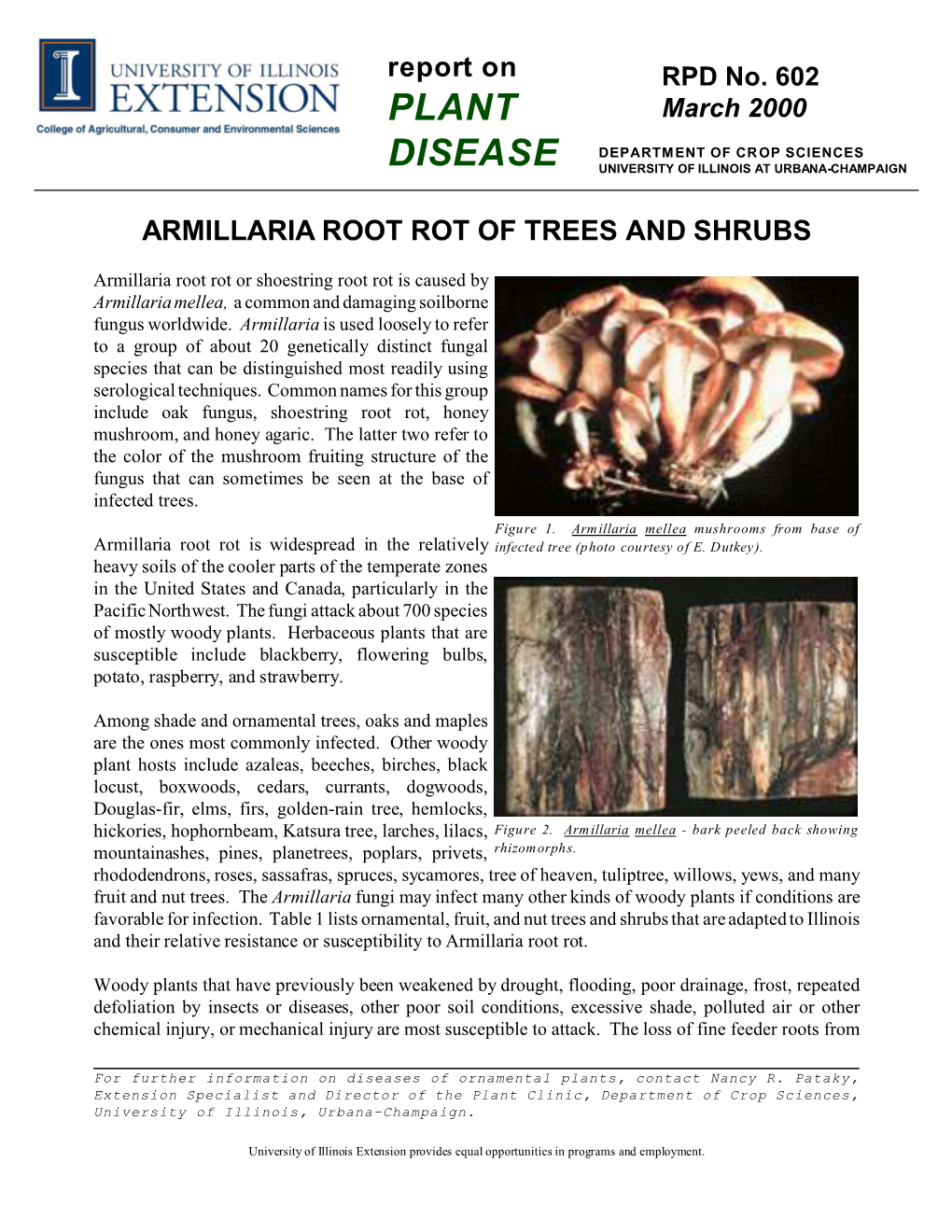

Armillaria Root Rot of Treees and Shrubs, RPD No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shoestring Root Rot - a Cause of Tree and Shrub Decline

PPFS-OR-W-05 Plant Pathology Fact Sheet Shoestring Root Rot - A Cause of Tree and Shrub Decline By John Hartman Most woody landscape plants are susceptible to shoestring root rot, cause of dieback and decline in the landscape. Diagnosis of this problem requires close examination of the base of the trunk which often reveals loose or decayed bark and dead cambium. By peeling back the bark one can often observe dark brown rhizomorphs (thick strands of hyphae), resembling narrow “shoestrings” (Figure 1). FIGURE 1. ARMILLARIA RHIZOMORPHS These rhizomorphs are signs of one or more species of Armillaria and perhaps other This disease is sometimes confused with related fungi, cause of shoestring root rot. Phytophthora root and collar rot. The decay Decayed roots with rhizomorphs growing associated with Phytophthora is usually a along their surface can be observed by darker brown color, decayed bark is more digging up the roots. moist, and rhizomorphs are absent. Creamy white fans of fungal mycelium Shoestring root rot has a very wide host range may also be observed under the bark. The and is most frequently observed in oaks, mushroom stage (Figure 2) of shoestring maples, pines, hornbeams, taxus, and fruit root rot sometimes develops in fall on dead trees in the landscape. Often, it is associated trees or decayed logs. with formerly wooded sites converted to landscapes because the fungus can persist Shoestring root rot is also called Armillaria for many years in decaying wood in soil. root rot, mushroom root rot, and oak root rot. Most trees with Armillaria root rot are trees Once trees or shrubs begin to show serious symptoms of decline, including dieback of twigs and branches, undersized and off-color leaves, increased trunk and limb sprouts (epicormic branching), and excessive fruit set, the decline is often not reversible. -

Root Diseases Diagnosis of Root Diseases Can Be Very Challenging Armillaria Root Disease • Symptoms Can Be Similar for Different Root Diseases • Below Ground Attacks

Root Diseases Diagnosis of root diseases can be very challenging Armillaria root disease • Symptoms can be similar for different root diseases • Below ground attacks but above ground Heterobasision annosum symptoms Annosus root disease • Signs are rare and often are produced once a year for short periods Chronosequence of stand and tree level symptoms of root diseases Source: Fig.12.10, p.312 Forest Health and Protection by Edmonds, R. L., J. K. Agee and R. I. Gara. 2011. Waveland Press, Long Grove, IL. 2nd ed. Used with permission from Waveland Press Dec.13, 2011. Tree level symptoms of Armillaria root disease CC BY 3.0. Borys M. Tkacz, USFS, Bugwood.orgTkacz, BorysM. 3.0. CC BY Tree level symptoms of Armillaria root disease • Dead saplings next to stumps, retaining needles • Roots of young trees grow into the dead roots infected by Armillaria, come into contact with rhizomorphs and get infected Signs of Armillaria root disease • Rhizomorphs: specialized highly adapted structures • Allow the pathogen to explore the “Rhizomorphs (thick fungal threads) of Armillaria mellea” Lairich Rig. CC BY-SA 2.0. environment and http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/933530 survive in the soil for decades • Contain melanin, a protective compound Cross section of rhizomorph showing differentiated tissue Signs of Armillaria root disease • Armillaria attacks the living cambium of tree roots • Mycelial fans form under the bark of infected trees • The mycelium is very strong and can grow under and lift the bark, leaving imprints Signs of Armillaria root disease -

ARMILLARIA ROOT ROT: a DISEASE of NATIVE and INTRODUCED TREES Forests Fact Sheet

ARMILLARIA ROOT ROT: A DISEASE December 2003 OF NATIVE AND INTRODUCED TREES ISSN 1440-2262 Ian W. Smith & David I. Smith, Forest Science Centre Background Armillaria root rot, unlike some familiar pests and diseases, occurs naturally in many forests of Victoria. This aggressive fungal pathogen has so far seriously damaged about 2000 ha of mixed species eucalypt forest in the Mt. Cole and Wombat State Forests with minor outbreaks in other areas of Victoria. It attacks many species of native trees and shrubs including eucalypts and wattles, and has also been recorded on introduced trees and shrubs growing in parks and botanical and domestic gardens. Symptoms and Signs of disease The fungus can kill trees and shrub species of any age and has a very wide host range. Young trees and seedlings may, over a period of a few weeks, suddenly wilt and the leaves fall. They may die within 3-6 months of the onset of the first symptoms. Larger trees, especially those with a sizeable trunk, die more slowly. The initial symptoms of sparse foliage and branch dieback may continue for up to 3 years before the remaining foliage begins to wilt, the leaves turn brown and the trees die (Figure 1). Other pathogens and environmental disorders can produce similar symptoms, so it is wise to check that Armillaria infection is present by examining a tree showing advanced disease symptoms. To do this, remove some of the inner bark at the base of the tree and look for fan-shaped, creamy-white fungal sheets (Figure 2). Often the bark tissue around the fungal sheets turns chocolate brown in colour. -

Detection, Recognition and Management Options for Armillaria Root Disease in Urban Environments

Detection, recognition and management options for Armillaria root disease in urban environments Richard Robinson Department of Environment and Conservation, Manjimup, WA 6258 Email: [email protected] Abstract Armillaria luteobubalina, the Australian honey fungus, is an endemic pathogen that attacks and kills the roots of susceptible trees and shrubs, causing a root rot. The fungus colonises the cambium and trees eventually die when the root collar is girdle and it spreads from host to host by root contact. The disease is referred to as armillaria root disease (ARD). In recent years, reports of ARD killing trees and shrubs in urban parks and gardens have increased. When investigated, infection is usually traced to stumps or the roots of infected trees that were left following clearing of the bush when towns or new suburbs were established. The Australian honey fungus is indigenous to southern Australia, and is common in all forest, woodland and some coastal heath communities. In undisturbed environments, ARD is generally not the primary cause of death of healthy forest or woodland trees but more usually it kills trees weakened by competition, age-related decline or environmental stress and disturbance. In gardens and parks, however, the honey fungus can become a particularly aggressive pathogen and in this situation no native or ornamental trees and shrubs appear to be resistant to infection. The life cycle of the fungus consists of a parasitic phase during which the host is infected and colonised. The time taken for plants to succumb to disease varies, but may take decades for large trees. A saprophytic phase follows, during which the root system and stump of the dead host is used by the fungus as a food base. -

Armillaria Root Rot on Urban Trees: Another Perspective to the Root Rot Problem in Newfoundland by Pritam Singh and G

Canadian Plant Disease Survey 63: 1, 1983 3 Armillaria root rot on urban trees: another perspective to the root rot problem in Newfoundland by Pritam Singh and G. C. Care w 1 This article is the first record of Armillaria root rot on ornamental and shade trees in Newfoundland. It discusses the distribution, severity and impact of the disease in urban areas, and implication of these findings on the root rot problem in this Region. Can. Plant Dis. Surv. 63: 1, 3-6, 1983. Cet article est le premier B mentionner la presence du pourridie-agaric sur les arbres ornementaux et B ombrage de Terre-Neuve. I1 discute de la distribution, de la severite et de I'impact de cette maladie en zone urbaine, et de I'implication de ces resultats sur le probkme de la pourriture des racines dans cette region. Introduction Later in the fall, twenty one more chlorotic and dead trees, showing similar symptoms and signs, were observed in this Armillaria or shoe-string root rot, caused by Armillaria mellea and eleven more home gardens and landscapes in five (Vahl ex Fr.) Kummer [= Armillariella mellea (Vahl ex Fr.) recently developed urban areas scattered across the Island Karst], is an important root disease affecting a variety of (Fig. 1). The infected trees belonged to seven species: Sitka forest, shade, ornamental and orchard trees and shrubs in spruce, Picea sitchensis (Bong.) Carr.; Canada yew, Taxus Canada and the United States. In Newfoundland, A. mellea is canadensis Marsh.; white birch, Betula papyrifera Marsh.; pin island-wide in distribution and has been observed both as a cherry, Prunus pensylvanica L.F.; American mountain-ash, parasite and saprophyte on 66 tree provenances belonging to Sorbus americana Marsh.; white spruce, Picea glauca 22 softwood and hardwood, indigenous and introduced (Moench) Voss; and black spruce, Picea mariana (Mill.) B.S.P. -

Armillaria Root Rot Robert Hartig (1839-1901) Is Considered the Father of Forest Pathology

Landscape Notes Vol 17 no. 5 & 6 January 2004 Disease Notes: Armillaria Root Rot Robert Hartig (1839-1901) is considered the father of Forest Pathology. It was he who in a monographic treatise in 1874 on Agaricus melleus described the pathology of what we now call Armillaria mellea. A. mellea causes root disease to such degree as to be one of the most prominent killers and decayers of deciduous and coniferous forest trees, orchard and ornamental trees, shrubs and other landscape plants throughout the world. It is the cause of many of the tree deaths I diagnose every year. Comments on the Life History and Survival Structures Armillaria can act as a primary pathogen, a stress-induced secondary invader, and as a saprophyte. The basis for this varied physiology is not understood. Armillaria has the ability to form many different kinds of structures based on its survival in wood. It can form mushrooms (basidiomes), mycelia, melanized cells or pseudosclerotial zone lines in wood, and rhizomorphs. The mushrooms of Armillaria typically form in winter in California after about two months of cold night and day temperatures. Their formation around infected trees or root pieces may occur every year consistently or intermittently from year to year depending on temperature conditions. They are always formed in clusters— never are they solitary. Mushrooms are always attached to woody material, either the bases of trees or roots near the surface. The mushroom has a cap and stalk or stipe which has a ring or annulus on it. (Fig. 1) The color is variable from honey colored to brown. -

An Example with Armillaria Root Disease

United States Department of Agriculture Approaches to Predicting Forest Service Rocky Mountain Potential Impacts of Climate Research Station Research Paper RMRS-RP-76 Change on Forest Disease: July 2009 An Example With Armillaria Root Disease Ned B. Klopfenstein, Mee-Sook Kim, John W. Hanna, Bryce A. Richardson, and John Lundquist Klopfenstein, Ned B.; Kim, Mee-Sook; Hanna, John W.; Richardson, Bryce A.; Lundquist, John E. 2009. Approaches to predicting potential impacts of climate change on forest disease: an example with Armillaria root disease. Res. Pap. RMRS-RP-76. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 10 p. Abstract Predicting climate change influences on forest diseases will foster forest management practices that minimize adverse impacts of diseases. Precise locations of accurately identi- fied pathogens and hosts must be documented and spatially referenced to determine which climatic factors influence species distribution. With this information, bioclimatic models can predict the occurrence and distribution of suitable climate space for host and pathogen species under projected climate scenarios. Predictive capacity is extremely limited for forest pathogens because distribution data are usually lacking. Using Armillaria root disease as an example, predictive approaches using available data are presented. Keywords: climate change, forest diseases, Armillaria, bioclimatic models, forest pathogens, global warming, MaxEnt Authors Ned B. Klopfenstein is a Research Plant Pathologist, with the U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Moscow, ID. John W. Hanna is a Biological Technician, with the U.S. Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Moscow, ID. Bryce A. Richardson is a Research Plant Geneticist, with the U.S. -

Armillaria Root Rot Wood in Soil, Infecting New Plantings and Spreading to Infect Nearby Plants (Figure 21)

Armillaria Root Rot wood in soil, infecting new plantings and spreading to infect nearby plants (Figure 21). Armillaria mellea Symptoms and Damage Armillaria root rot infects many crops and native and orna- mental plants. Common hosts include avocado, cherimoya, The Armillaria fungus can become well established in roots citrus, and oak trees. The fungus persists in infested roots and and the root crown before any symptoms are visible above ground. Infected trees usually die prematurely, and if they are young trees they often die quickly after infection. Mature trees may die quickly or slowly, or they may recover at least temporarily if conditions become good for tree growth and poor for disease development. Wilted, downward-hanging foliage is often the first obvi- ous symptom of Armillaria root rot. Other symptoms include yellowing of the foliage, leaf drop, and dieback of upper limbs. During rainy fall and winter periods, short-lived mushrooms often appear around the base of Armillaria-infected trees. The mushroom caps vary in color from off-white to honey-yellow to almost black. Each cap is about 1 to 10 inches (2.5–25 cm) in diameter. The mushrooms always occur in groups, never singly. Mushrooms have a ring on the stalk just under the cap This wilted, downward-hanging foliage is a symptom of infection by Armillaria mellea. Other symptoms of Armillaria root rot include yellowing of foliage, leaf drop, and dieback of upper limbs. JACK KELLY CLARK JACK KELLY During the rainy fall and winter, short-lived mushrooms often grow The most reliable sign of Armillaria root rot is white, cottony fungal around the base of Armillaria-infected trees such as this almond. -

Armillaria (Shoestring) Root Rot

EB1776 ARMILLARIA (SHOESTRING) ROOT ROT Shoestring root rot is caused by a group of fungi known as Armillaria. At least 12 species of Armillaria have been shown to cause root rots, but since it is very difficult to distinguish between these fungi, and many of these disease situations have not been thoroughly investigated, they are commonly refered to only as Armillaria melea. These fungi rot the roots of many different kinds of plants. Most often this disease is found on trees and shrubs such as fir, oak, pine, rhododendron, lilac, and dogwood. However, it is not restricted to woody plants and has been found on raspberry and strawberry. Plants which are not growing well are more likely to be seriously damaged. Symptoms. Symptoms of this root rot on above-ground parts of a plant generally appear as stunting, yellowing, or browning of leaves of needles, which may drop. Symptoms occur over the whole plant. Foliage may look unhealthy and become more sparse over a period of several years or may show no evidence of any problems but suddenly die. Similar symptoms may be caused by other factors such as general lack of plant care or weather stress. Armillaria root rot can be distinguished from other problems by examining the lower trunk and roots. If Armillaria is responsible for the problem, a white, generally felt-like fungus growth can be seen between the bark and the wood when the bark is carefully peeled from the wood. At the edge of a diseased area, the white fungus growth normally assumes a characteristic fan-shape. -

Armillaria Root Rot (Also Known As Mushroom Root Rot, Shoestring Root Rot, Honey Mushroom Rot) 1 Laura Sanagorski, Aaron Trulock, and Jason Smith2

ENH1217 Armillaria Root Rot (Also known as Mushroom Root Rot, Shoestring Root Rot, Honey Mushroom Rot) 1 Laura Sanagorski, Aaron Trulock, and Jason Smith2 Summary Signs and Symptoms Armillaria root rot is a disease that decays the root system Trees with Armillaria root rot display one or more of the of many common trees and shrubs. It is caused by several following symptoms: species of Armillaria, fungi that can be recognized by the clusters of yellow to honey-colored mushrooms that emerge • Fading, wilting, or thin foliage (Figure 1) during moist conditions. The disease is often lethal, and • Overall decline infected trees may have wilting branches, branch dieback, • Dead branches and stunted growth. Infected trees and shrubs should be removed and replaced with resistant species (Table 1). • Branch or trunk failure • Dieback (Figure 2) Introduction • Stunted growth Armillaria spp. cause root and butt rot of trees and shrubs • Death (Figure 2) worldwide, from tropical to boreal regions (Sinclair and Lyon 2005). Armillaria spp. have a wide host range, includ- During high winds, trees infected with Armillaria may ing many hardwoods and conifers. The fungus infects the break from the weakened base and cause damage or injury. roots and bases of trees, causing them to decay, weaken, Large trees infected with Armillaria are considered hazard or die. Some species of Armillaria are primary pathogens, trees and should be removed when near targets, such as capable of attacking and killing trees, but others are oppor- property or people. tunistic pathogens that kill only unhealthy or stressed trees. In some western conifer forests, Armillaria is considered a Armillaria root rot can be easily recognized by a few major forest pathogen, and silvicultural practices must be distinct signs. -

Relative Resistance of Grapevine Rootstocks to Armillaria Root Disease

408 – Baumgartner and Rizzo Relative Resistance of Grapevine Rootstocks to Armillaria Root Disease Kendra Baumgartner1* and David M. Rizzo2 Abstract: Grapevine rootstocks were screened for resistance to infection by Armillaria mellea, the pathogen that causes Armillaria root disease. The first objective was to determine which factors hasten colonization of grape- vines by A. mellea in order to develop the most rapid inoculation technique. Results showed that wounding the root collar bark and vascular cambium did not significantly increase infection rate (p = 1.0), that young vines were infected significantly faster than older vines (p = 0.03), and that fine roots (≤5 mm diam) were not susceptible to infection. Based on these findings, the inoculation technique was modified and used to inoculate dormant rootings of eight rootstocks in the greenhouse. After two years, the root collars were examined for the presence of myce- lial fans of A. mellea and infection was confirmed by culture. The rootstock Freedom had the lowest frequency of infection (7%) and was the most resistant rootstock (p = 0.0016). Rootstocks O39-16, 5C, Riparia Gloire, and 3309C had the highest frequencies of infection with 63%, 73%, 79%, and 85%, respectively. Rootstocks St. George, Ramsey, and 110R had intermediate frequencies of infection. Results suggest that Freedom and, to a lesser extent, St. George, Ramsey, and 110R will be useful components of an integrated management strategy for Armillaria root disease. Resistant rootstocks may decrease the rate of colonization of grapevines in A. mellea-infested vineyards, thereby reducing yield losses from Armillaria root disease. Key words: Armillaria mellea, disease resistance, screening technique, Vitis vinifera Armillaria root disease of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) is cronutrients, delayed ripening of fruit, and eventual death caused by Armillaria mellea (Vahl:Fr.) P. -

Distribution and Characterization of Armillaria Complex in Atlantic Forest Ecosystems of Spain

Article Distribution and Characterization of Armillaria Complex in Atlantic Forest Ecosystems of Spain Nebai Mesanza 1,*, Cheryl L. Patten 2 and Eugenia Iturritxa 1,* 1 Production and Plant Protection, Neiker Tecnalia, Apartado 46, Vitoria Gasteiz 01080, Spain 2 Department of Biology, University of New Brunswick, P.O. Box 4400, Fredericton, NB E3B 5A3, Canada; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (N.M.); [email protected] (E.I.); Tel.: +34-637-436-343 (E.I.) Received: 9 May 2017; Accepted: 28 June 2017; Published: 30 June 2017 Abstract: Armillaria root disease is a significant forest health concern in the Atlantic forest ecosystems in Spain. The damage occurs in conifers and hardwoods, causing especially high mortality in young trees in both native forests and plantations. In the present study, the distribution of Armillaria root disease in the forests and plantations of the Basque Country is reported. Armillaria spp. were more frequently isolated from stands with slopes of 20–30% and west orientation, acid soils with high permeability, deciduous hosts, and a rainfall average above 1800 mm. In a large-scale survey, 35% of the stands presented Armillaria structures and showed disease symptoms. Of the isolated Armillaria samples, 60% were identified using molecular methods as A. ostoyae, 24% as A. mellea, 14% as A. gallica, 1% as A. tabescens, and 1% as A. cepistipes. In a small scale sampling, population diversity was defined by somatic compatibility tests and Universally Primed-PCR technique. Finally, the pathogenicity of A. mellea, the species with the broadest host range, was determined on different tree species present in the Atlantic area of Spain in order to determine their resistance levels to Armillaria disease.