Chapter 1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tacsound On-Line

TACSound is a non-profit division of the Teachers' Association (Canada) affiliated with the Royal Scottish Country Dance Society. Your volunteer manager, Lydia Hedge, is TACSound pleased to offer you a unique selection of available recorded music for Scottish Country Dancing and your listening pleasure. Recorded Music Division of TO ORDER: Teachers’ Association (Canada) ONLINE : Go to http://sound.tac-rscds.org Select the albums you want, add them to your CART then proceed to the CHECKOUT pages to select shipping method and payment option. Payment online can be by PayPal or Invoice/Cheque (which includes VISA). If you are a member of TAC, you are entitled to a 5% discount . You need a Discount Coupon to receive this online. Contact Lydia for your coupon number. (See next page for more details about discounts) BY MAIL : Complete an Order Form (back of this catalogue) including Item #, Title, Quantity. Mail it to: TACSound ℅ Lydia Hedge 624 Three Fathom Harbour Road RR#2, Head of Chezzetcook Nova Scotia Canada B0J 1N0 Do not send payment but please note on the order form whether you want to remit in Canadian dollars, U.S. dollars, or Pounds Sterling. We will send an invoice at the current exchange rate with the goods. September 2013 Catalogue : 902-827-2033 BY PHONE BY EMAIL : Just compose an email, indicating which albums you want. Send it to: All Prices Shown are in Canadian Dollars [email protected] All prices shown in the catalogue are in Canadian dollars and are subje ct to change without notice because of price changes from our suppliers or currency fluctuations. -

Off the Beaten Track

Off the Beaten Track To have your recording considered for review in Sing Out!, please submit two copies (one for one of our reviewers and one for in- house editorial work, song selection for the magazine and eventual inclusion in the Sing Out! Resource Center). All recordings received are included in “Publication Noted” (which follows “Off the Beaten Track”). Send two copies of your recording, and the appropriate background material, to Sing Out!, P.O. Box 5460 (for shipping: 512 E. Fourth St.), Bethlehem, PA 18015, Attention “Off The Beaten Track.” Sincere thanks to this issue’s panel of musical experts: Richard Dorsett, Tom Druckenmiller, Mark Greenberg, Victor K. Heyman, Stephanie P. Ledgin, John Lupton, Angela Page, Mike Regenstreif, Seth Rogovoy, Ken Roseman, Peter Spencer, Michael Tearson, Theodoros Toskos, Rich Warren, Matt Watroba, Rob Weir and Sule Greg Wilson. that led to a career traveling across coun- the two keyboard instruments. How I try as “The Singing Troubadour.” He per- would have loved to hear some of the more formed in a variety of settings with a rep- unusual groupings of instruments as pic- ertoire that ranged from opera to traditional tured in the notes. The sound of saxo- songs. He also began an investigation of phones, trumpets, violins and cellos must the music of various utopian societies in have been glorious! The singing is strong America. and sincere with nary a hint of sophistica- With his investigation of the music of tion, as of course it should be, as the Shak- VARIOUS the Shakers he found a sect which both ers were hardly ostentatious. -

Resource Guide for Educators and Students Grades 4–12

Resource Guide for Educators and Students Grades 4–12 What is traditional music? It’s music that's passed on from one person to another, music that arises from one or more cultures, from their history and geography. It's music that can tell a story or evoke emotions ranging from celebratory joy to quiet reflection. Traditional music is usually played live in community settings such as dances, people's houses and small halls. In each 30-minute episode of Carry On™, musical explorer and TikTok sensation Hal Walker interviews a musician who plays traditional music. Episodes air live, allowing students to pose questions. Programs are then archived so you can listen to them any time from your classroom or home. Visit Carry On's YouTube channel for live shows and archived episodes. Episode 7, Tina Bergmann Tina Bergmann is a fourth-generation musician from northeast Ohio who began performing at age 8 and teaching at age 12. She learned the mountain dulcimer from her mother in the aural tradition (by ear) and the hammered dulcimer from builder, performer and West Virginia native Loy Swiger. She makes her living teaching and performing. She performs on her own, with her husband bassist Bryan Thomas and with two groups, Apollo's Fire and Hu$hmoney string band. Even though the hammered dulcimer has strings, it's considered a percussion instrument because the strings are struck (like the piano). Percussion instruments like the hammered dulcimer can play melody and harmony. But because the sound fades quickly after the string is struck, it has to be struck again and again—and so rhythm becomes an important musical element with this (and any) percussion instrument. -

Hornpipes, Jigs, Strathspeys, and Reels Are Different Types of Celtic Dances

Hornpipes, Jigs, Strathspeys, and Reels are different types of Celtic dances. Piobaireachd is an ancient and poetic style of music that is best played for somber occasions. Name Type Hark! The Herald Angels Sing Christmas Here We Come A Wassailing Christmas I Saw Three Ships Christmas Jingle Bells Christmas Little Drummer Boy Christmas O Come All Ye Faithful Christmas Joy to The World Christmas We Wish You a Merry Christmas Christmas Alex and Hector Hornpipe Ballachulish Walkabout, The Hornpipe Crossing the Minch Hornpipe Jolly Beggarman, The Hornpipe Papas Fritas Hornpipe Rathven Market Hornpipe Redondo Beach Hornpipe Sailor's Hornpipe, The Hornpipe Streaker, The Hornpipe Walrus, The Hornpipe Alan MacPherson of Mosspark Jig Banjo Breakdown, The Jig Blue Cloud, The Jig Brest St. Marc (The Thunderhead) Jig Cork Hill Jig Ellis Kelly's Delight Jig Glasgow City Police Pipers, The Jig Gold Ring, The Jig Honey in the Bag Jig Irish Washerwoman, The Jig Judge's Delimma, The Jig Paddy's Leather Breeches Jig Paddy's Leather Breeches (D. Johnstone setting) Jig Patrick's Romp Jig Phat John Jig Scotland the Brave Jig Wee Buns Jig 79th's Farewell to Gibraltar March All the Blue Bonnets are Over the Border March Argylls Crossing the River Po March Arthur Bignold of Lochrosque March Atholl Highlanders March Balmoral Highlanders March Barren Rocks of Aden, The March Battle of the Somme March Battle of Waterloo March Bonnie Charlie March Bonny Dundee March Brown Haired Maiden, The March Cabar Feidh March Castle Dangerous March Cullen Bay March Farewell -

1 Study Guide for SONG of EXTINCTION

Study Guide for SONG OF EXTINCTION (a play by E. M. Lewis) Prepared by Robert F. Cohen, Ph.D. Director, Hostos Book-of-the-Semester Project Fall 2012 1 SONG OF EXTINCTION by E. M. Lewis Pre-reading Activities A. Considering the Title: Song of Extinction In small groups, consider these questions. 1. Do the words “song” and “extinction” have positive or negative associations, or both? _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ 2. Is there a difference between “extinction” (verb = extinguish) and “extermination” (verb = exterminate)? Are they both “natural” processes, or is one more natural than the other? _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ 3. Is the title of the play a positive one or a negative one? Write down the thoughts of the members of your group here. _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________________________________________ B. Identifying the Characters and Visualizing the Setting 1. Setting the Stage for the Action Look -

FW May-June 03.Qxd

IRISH COMICS • KLEZMER • NEW CHILDREN’S COLUMN FREE Volume 3 Number 5 September-October 2003 THE BI-MONTHLY NEWSPAPER ABOUT THE HAPPENINGS IN & AROUND THE GREATER LOS ANGELES FOLK COMMUNITY Tradition“Don’t you know that Folk Music is Disguisedillegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEY of the Wicked Tinkers THE FOLK ART OF MASKS BY BROOKE ALBERTS hy do people all over the world end of the mourning period pro- make masks? Poke two eye-holes vided a cut-off for excessive sor- in a piece of paper, hold it up to row and allowed for the resump- your face, and let your voice tion of daily life. growl, “Who wants to know?” The small mask near the cen- The mask is already working its ter at the top of the wall is appar- W transformation, taking you out of ently a rendition of a Javanese yourself, whether assisting you in channeling this Wayang Topeng theater mask. It “other voice,” granting you a new persona to dram- portrays Panji, one of the most atize, or merely disguising you. In any case, the act famous characters in the dance of masking brings the participants and the audience theater of Java. The Panji story is told in a five Alban in Oaxaca. It represents Murcielago, a god (who are indeed the other participants) into an arena part dance cycle that takes Prince Panji through of night and death, also known as the bat god. where all concerned are willing to join in the mys- innocence and adolescence up through old age. -

Tunes 2001 Liner Notes

Tunes 2001: 65 tunes from Laura Risk Extended liner notes Note: these liner notes were written in 2001, when cassette tapes were still in everyday use! After making (at a rough count) close to a hundred copies of various repertoire tapes for my students over the last few years, only to find that the tapes were plagued with distortion and would often play back at the wrong pitch, I decided to join the Information Age and make these CDs. How did I choose these particular tunes? This is a teaching CD, so I picked the tunes I like to teach. These tunes are memorable, fun to learn, fun to play, and for the most part, well- known in the greater world of fiddling. Many of them offer a particular technical or stylistic challenge. Many of them are particularly well-suited to beginning-level fidders. On these CDs, I play each tune fast and then slow (unless it's a slow air -- then I just play it slow). These CDs are meant to be used in conjunction with private or group lessons, so I haven't provided much commentary. Here's an example of what you'll find in these notes: 5-6 Soldier's Joy 5-6 means that this tune, Soldier's Joy, is on tracks 5-6 of the CD. On track 5, I play the tune at tempo. On track 6, I play it slow. D major reel; Shetland/Scotland/New England 'D major reel' means that this tune is a reel in the key of D major. -

The Piobaireachd Society of Central Pennsylvania What Is Piobaireachd? There Were Several Hereditary Lines of Pipers Throughout the Highlands

Volume 5, Issue 2 March 2018 The Piobaireachd Society of Central Pennsylvania What is Piobaireachd? There were several hereditary lines of pipers throughout the highlands. The “Piobaireachd” literally means “pipe most important line comes through the playing” or “pipe music.” However, in MacCrimmons of Skye. The recent times it has come to represent the MacCrimmons were hereditary pipers to type of music known as Ceol Mor. The the MacLeods on the Isle of Skye. The music for the Highland Bagpipe can be MacCrimmons were given lands near divided into three classes of music: Ceol Dunvegan Castle, known as Boreraig. Beag, Ceol Meadhonach, and Ceol Mor. The MacCrimmon cairn (stone Ceol Beag (Little Music) is the gaelic monument) was recently erected to mark name for the classification of tunes the place where the MacCrimmons held known as Marches, strathspeys & reels. their famous piping school at Boreraig. Marches came out of the military tradition On the solo competition circuit, of the 19th century. Strathspeys & Reels piobaireachd is where it’s at. The came out of the dance traditions. Highland Society gold medals at the Ceol Meadhonach (Middle Music) refers Argyllshire Gathering in Oban and the to the jigs, hornpipes and slow airs. Slow Northern Meeting in Inverness are airs were played by the ancient piping considered the pinnacle achievements by masters, however, jigs and hornpipes are many pipers. fairly modern additions to a piper’s Piobaireachd truly is Ceol Mor, the repertoire. “Great Music” of the Highland bagpipe. Ceol Mor (Great Music) is the classical music for the Highland Bagpipe, also known as, piobaireachd. -

Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures: Promoting Heritage Edited by Yves Goudineau

Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures: Promoting Heritage Edited by Yves Goudineau UNESCO PUBLISHING MEMORY OF PEOPLES 34_Laos_GB_INT 26/06/03 10:24 Page 1 Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures 34_Laos_GB_INT 26/06/03 10:24 Page 3 Laos and Ethnic Minority Cultures: Promoting Heritage Edited by YVES GOUDINEAU Memory of Peoples | UNESCO Publishing 34_Laos_GB_INT 7/07/03 11:12 Page 4 The authors are responsible for the choice and the presentation of the facts contained in this book and for the opinions expressed therein, which are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not commit the Organization. The designations employed and the presentation of material throughout this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. UNESCO wishes to express its gratitude to the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs for its support to this publication through the UNESCO/Japan Funds-in-Trust for the Safeguarding and Promotion of Intangible Heritage. Published in 2003 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization 7, place de Fontenoy F-75352 Paris 07 SP Plate section: Marion Dejean Cartography and drawings: Marina Taurus Composed by La Mise en page Printed by Imprimerie Leclerc, Abbeville, France ISBN 92-3-103891-5 © UNESCO 2003 Printed in France 34_Laos_GB_INT 26/06/03 10:24 Page 5 5 Foreword YVES GOUDINEAU It is quite clear to every observer that Laos owes part of its cultural wealth to the unique diversity which resides in the bosom of the different populations that have settled on its present territory down the ages, bringing with them a mix of languages, beliefs and aesthetic traditions. -

Princess Margaret of the Isles Memorial Prize for Senior Clàrsach, 16 June 2018 Finallist Biographies and Programme Notes

Princess Margaret of the Isles Memorial Prize for Senior Clàrsach, 16 June 2018 Finallist biographies and programme notes Màiri Chaimbeul is a Boston, Massachusetts-based harp player and composer from the Isle of Skye. Described by Folk Radio UK as "astonishing", she is known for her versatile sound, which combines deep roots in Gaelic tradition with a distinctive improvising voice and honed classical technique. Màiri tours regularly throughout the UK, Europe and in North America. Recent highlights include performances at major festivals and events including the Cambridge Folk Festival, Fairport's Cropredy Convention, Hillside Festival (Canada), WGBH's St Patrick's Day Celtic Sojourn, Celtic Connections, and Encuentro Internacional Maestros del Arpa, Bogota, Colombia. Màiri can currently be heard regularly in duo with US fiddler Jenna Moynihan, progressive-folk Toronto group Aerialists, with her sister Brìghde Chaimbeul, and with legendary violinist Darol Anger & the Furies. She is featured in series 2 of Julie Fowlis and Muireann NicAmhlaoibh's BBC Alba/TG4 television show, Port. Màiri was twice- nominated for the BBC Radio 2 Young Folk Award, finalist in the BBC Young Traditional & Jazz Musicians of the year and twice participated in Savannah Music Festival's prestigious Acoustic Music Seminar. She is a graduate of the Berklee College of Music, where she attended with full scholarship, and was awarded the prestigious American Roots Award. Màiri joins the faculty at Berklee College of Music this year as their lever harp instructor. Riko Matsuoka was born in the Osaka prefecture of Japan and began playing the piano at the age of three. She started playing the harp at the age of fourteen. -

The Tsymbaly Maker and His Craft: the Ukrainian Hammered Dulcimer in Alberta

m Canadian Series in Ukrainian Ethnology Volume I • 1991 Tsymbaly daker and His Craft The Ukrainian Hammered Dulcimer In Alberta Mark Jaroslav Bandera Huculak Chair of Ukrainian Culture & Ethnography Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press Canadian Series in Ukrainian Ethnology THE TSYMBALY MAKER AND HIS CRAFT: THE UKRAINIAN HAMMERED DULCIMER IN ALBERTA Mark Jaroslav Bandera Publication No. 1-1991 Huculak Chair of Ukrainian Culture and Ethnography Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press University of Alberta Edmonton, Alberta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study has been possible only with the cooperation of the tsymbaly makers of east central Alberta and particularly with the support and patience of Mr. Tom Chychul. Mr. Chychul is a fine craftsman and a rich source of information on tsymbaly and the community associated with them. Mr. Chychul continues to make tsymbaly at the time of printing and can be contacted at R.R. 4 Tofield, Alberta TOB 4J0 Drawings were executed by Alicia Enciso with Yarema Shulakewych of the Spectra Architectural Group. Cover design by Kevin Neinhuis. Huculak Chair of Ukrainian Culture and Ethnography and Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press University of Alberta Canadian Series in Ukrainian Ethnology Editors Bohdan Medwidsky and Andriy Nahachewsky Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Bandera, Mark Jaroslav, 1957- The tsymbaly maker and his craft (Canadian series in Ukrainian ethnology ; 1) Co-published by the Huculak Chair of Ukrainian Culture and Ethnography, University of Alberta. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-920862-80-2 1. Ukrainian Canadians—Alberta—Music—History and criticism. 2. Musical instruments—Construction—Alberta. 3. Cimbalom. I. University of Alberta. Huculak Chair of Ukrainian Culture and Ethnography. -

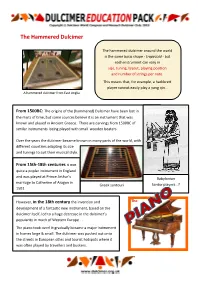

The Hammered Dulcimer

The Hammered Dulcimer The hammered dulcimer around the world is the same basic shape - trapezoid - but each instrument can vary in size, tuning, layout, playing position and number of strings per note. This means that, for example, a hackbrett player cannot easily play a yang qin… A hammered dulcimer from East Anglia From 1500BC: The origins of the (hammered) Dulcimer have been lost in the mists of time, but some sources believe it is an instrument that was known and played in Ancient Greece. There are carvings from 1500BC of similar instruments being played with small wooden beaters. Over the years the dulcimer became known in many parts of the world, with different countries adapting its size and tunings to suit their musical style. From 15th-18th centuries it was quite a poplar instrument in England and was played at Prince Arthur’s Babylonian marriage to Catherine of Aragon in Greek santouri Santur players…? 1501. However, in the 18th century the invention and The development of a fantastic new instrument, based on the dulcimer itself, led to a huge decrease in the dulcimer’s popularity in much of Western Europe . The piano took over! It gradually became a major instrument in homes large & small. The dulcimer was pushed out onto the streets in European cities and tourist hotspots where it was often played by travellers and buskers. The hammered dulcimer can be quiet or loud depending on several factors, one of them being the type of ‘hammers’ used. They come in various shapes & sizes and are traditionally (but not exclusively) made from..