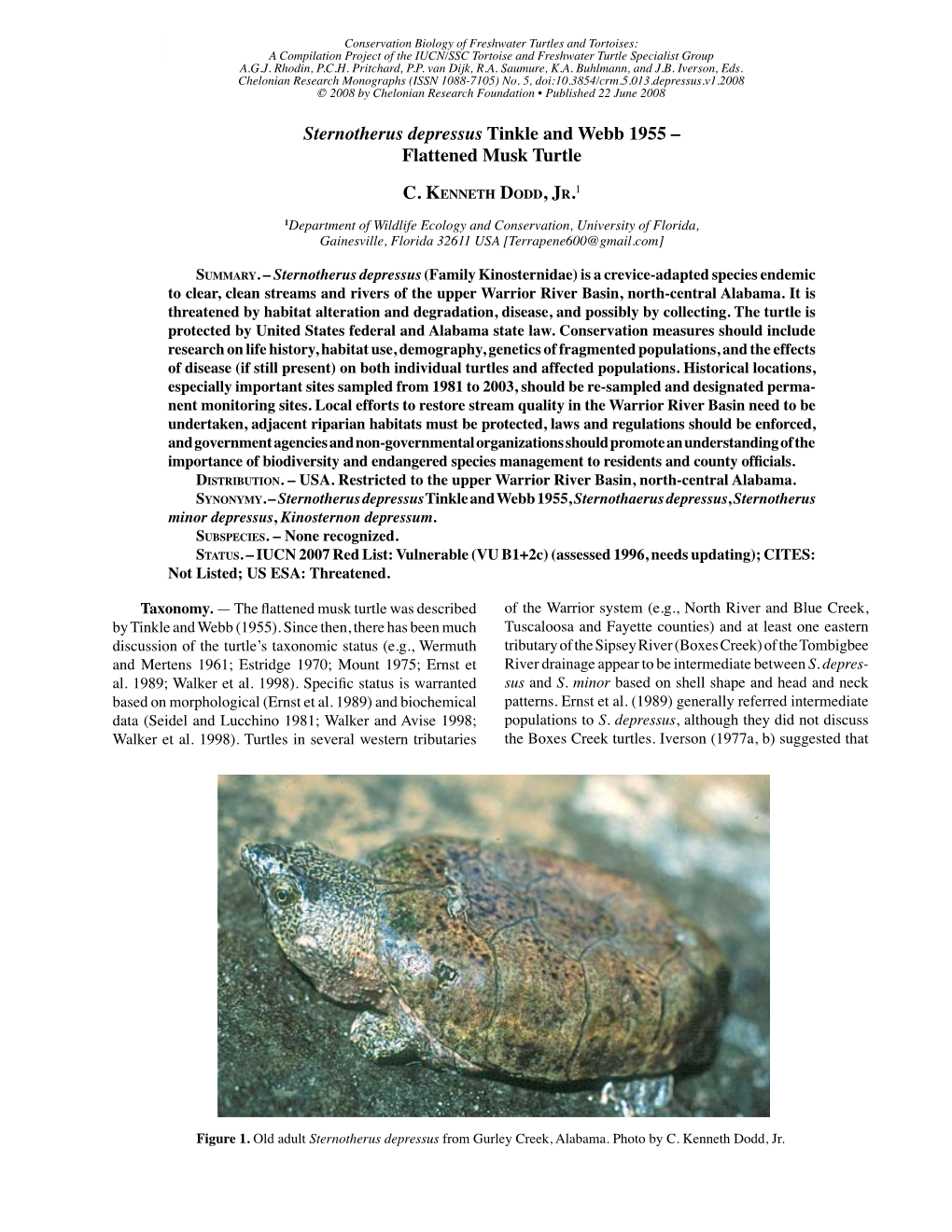

Flattened Musk Turtle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ecology and Evolutionary History of Two Musk Turtles in the Southeastern United States

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 2020 The Ecology and Evolutionary History of Two Musk Turtles in the Southeastern United States Grover Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Grover, "The Ecology and Evolutionary History of Two Musk Turtles in the Southeastern United States" (2020). Dissertations. 1762. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1762 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTIONARY HISTORY OF TWO MUSK TURTLES IN THE SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES by Grover James Brown III A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Biological, Environmental, and Earth Sciences at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved by: Brian R. Kreiser, Committee Co-Chair Carl P. Qualls, Committee Co-Chair Jacob F. Schaefer Micheal A. Davis Willian W. Selman II ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Brian R. Kreiser Dr. Jacob Schaefer Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Director of School Dean of the Graduate School May 2020 COPYRIGHT BY Grover James Brown III 2020 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT Turtles are among one of the most imperiled vertebrate groups on the planet with more than half of all species worldwide listed as threatened, endangered or extinct by the International Union of the Conservation of Nature. -

Diets of Freshwater Turtles Often Reflect the Availability of Food Resources in the Environment

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 8(3):561−570. HerpetologicalSubmitted: 26 March Conservation 2013; Accepted: and Biology 21 October 2013; Published: 31 December 2013. RazoR-Backed Musk TuRTle (SternotheruS carinatuS) dieT acRoss a GRadienT of invasion carla l. atkinSon1,2, 3 1Oklahoma Biological Survey, 111 E. Chesapeake St., Norman, OK 73019 2Department of Biology and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Graduate Program, University of Oklahoma, Norman, Ok 73019 3Present Address: Dept. of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Corson Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 e-mail: [email protected] abstract.—diets of freshwater turtles often reflect the availability of food resources in the environment. accordingly, bottom- feeding turtles’ diets are typically composed of benthic macroinvertebrate fauna (e.g., insects and mollusks). However, the composition of benthic systems has changed because many freshwater ecosystems have been invaded by non-native species, including bivalve species such as the asian clam, corbicula fluminea. i studied the diet of Sternotherus carinatus, the Razor- backed Musk Turtle, in southeastern oklahoma across three zones of corbicula abundances: no corbicula, moderate corbicula densities, and high corbicula densities. i hypothesized that the composition of corbicula in the diet would increase with increased abundance of corbicula in the riverine environment. Turtles were caught by snorkel surveys in the little and Mountain fork rivers and kept overnight for the collection of fecal samples. The diet was similar to that found in previous studies on S. carinatus except that corbicula is a new component of the diet and composed the majority of the diet in high-density corbicula areas. an index of Relative importance (iRi) showed that corbicula was the most important prey item in the areas with high corbicula density, was equally as important as gastropods in the areas with moderate corbicula density, and was absent from the diet in areas without corbicula. -

Sternotherus Depressus)

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title Phylogenetic distinctiveness of a threatened aquatic turtle (Sternotherus depressus) Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/207246m8 Journal Conservation Biology, 12(3) ISSN 0888-8892 Authors Walker, D Ortí, G Avise, JC Publication Date 1998 DOI 10.1111/j.1523-1739.1998.97056.x License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Phylogenetic Distinctiveness of a Threatened Aquatic Turtle (Sternotherus depressus) DEETTE WALKER,* GUILLERMO ORTÍ,* AND JOHN C. AVISE Department of Genetics, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602, U.S.A. Abstract: The musk turtle (Sternotherus minor) is common throughout the southeastern United States. In 1955 a morphologically atypical form confined to the Black Warrior River System in Alabama was discov- ered and accorded full species status as S. depressus, the “flattened musk turtle.” Questions remain about the taxonomic status and evolutionary history of the flattened musk turtle because (1) the geographic distribu- tion of S. depressus is nested within the range of S. minor; (2) the flattened shell might be a recently evolved anti-predator adaptation; and (3) reports exist of intergrades between S. depressus and S. minor. We gener- ated and employed sequence data from mitochondrial DNA to address the phylogenetic distinctiveness and phylogeographic position of S. depressus relative to all other musk and mud turtles (Kinosternidae) in North America. The flattened musk turtle forms a well-supported monophyletic group separate from S. minor. Ge- netic divergence observed between S. depressus and geographic populations of S. -

In AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): Species in Red = Depleted to the Point They May Warrant Federal Endangered Species Act Listing

Southern and Midwestern Turtle Species Affected by Commercial Harvest (in AR, FL, GA, IA, KY, LA, MO, OH, OK, SC, TN, and TX): species in red = depleted to the point they may warrant federal Endangered Species Act listing Common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) – AR, GA, IA, KY, MO, OH, OK, SC, TX Florida common snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina osceola) - FL Southern painted turtle (Chrysemys dorsalis) – AR Western painted turtle (Chrysemys picta) – IA, MO, OH, OK Spotted turtle (Clemmys gutatta) - FL, GA, OH Florida chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia chrysea) – FL Western chicken turtle (Deirochelys reticularia miaria) – AR, FL, GA, KY, MO, OK, TN, TX Barbour’s map turtle (Graptemys barbouri) - FL, GA Cagle’s map turtle (Graptemys caglei) - TX Escambia map turtle (Graptemys ernsti) – FL Common map turtle (Graptemys geographica) – AR, GA, OH, OK Ouachita map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis) – AR, GA, OH, OK, TX Sabine map turtle (Graptemys ouachitensis sabinensis) – TX False map turtle (Graptemys pseudogeographica) – MO, OK, TX Mississippi map turtle (Graptemys pseuogeographica kohnii) – AR, TX Alabama map turtle (Graptemys pulchra) – GA Texas map turtle (Graptemys versa) - TX Striped mud turtle (Kinosternon baurii) – FL, GA, SC Yellow mud turtle (Kinosternon flavescens) – OK, TX Common mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum) – AR, FL, GA, OK, TX Alligator snapping turtle (Macrochelys temminckii) – AR, FL, GA, LA, MO, TX Diamond-back terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) – FL, GA, LA, SC, TX River cooter (Pseudemys concinna) – AR, FL, -

Sternotherus Depressus) in the Bankhead National Forest, Alabama

Home Range, Activity, Movement, and Habitat Selection of the Flattened Musk Turtle (Sternotherus depressus) in the Bankhead National Forest, Alabama by Arthur Joseph Jenkins A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Auburn, Alabama August 3, 2019 Keywords: Flattened Musk Turtle, Sternotherus depressus, Habitat Selection, Home Range, Movement, Activity Copyright 2019 by Arthur Joseph Jenkins Approved by Daniel Warner, Chair, Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences John Feminella, Professor of Biological Sciences David Steen, Research Ecologist, Georgia Sea Turtle Center Todd Steury, Associate Professor of Forestry and Wildlife Sciences Abstract The Flattened Musk Turtle, Sternotherus depressus, is an imperiled aquatic species endemic to the Upper Black Warrior watershed in Alabama. As one of the most understudied turtles in the United States, little is known about its habits. This is especially true of their spatial ecology, one of the most important fields of ecological knowledge to inform management and conservation practices. To fill this information gap, this study employs radio telemetry, trapping, habitat, and wading (visual encounter) surveys to explore aspects of S. depressus spatial ecology in Bankhead National Forest (BNF) by describing home range and areas of core use, identifying factors that affect activity and movement, and modeling habitat selection on multiple levels (second-order, or population level; third-order, or patch level; and fourth-order, or microhabitat level). Home ranges, quantified as stream length inhabited, of 21 individuals averaged 332 m, ranging from 22 to 957 m. Areas of core stream use were also quantified as stream length by kernel density estimation using the Sheather-Jones plug-in method for individual bandwidth selection. -

Common Musk Turtle

Common Musk Turtle Common Musk Turtle [Stinkpot] - Pl. 1 (Sternotherus odoratus) Identification: 2" - 5 3/8". The Common Musk Turtle has an olive-brown to black carapace, sometimes marked with dark spots or streaks. The carapace is smooth and domed, and may have green algae growing on its surface. The plastron is yellow to brown. Two key identifying features on the relatively small plastron are: (1) a single hinge, and (2) squarish pectoral scutes (just in front of the hinge). Other key features are two light stripes on the head (these may be hidden by dark pigment), and barbels (small fleshy projections) on the chin and throat. Where to find them: The Common Musk Turtle can be found in still or slow-moving bodies of water, where it prefers to walk slowly along the bottom. It basks just at or below the surface, but can also be seen basking on fallen trees and branches overhanging the water. When to find them: Active April through October. Range: Entire state. Note: In New Jersey, the turtle most similar to this is the Eastern Mud Turtle, which lacks the stripes and the barbels, and has two hinges instead of one. Common Musk Turtle (Sternotherus odoratus) - text pg. 10 Key Features - Carapace: smooth & domed. - Plastron: small with single hinge. - Barbels on chin, two light stripes on head. New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife ~ 2003 Excerpt from: Schwartz, V. & D. Golden, “Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of New Jersey”. New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife 2002. Order the complete guide at - http://www.state.nj.us/dep/fgw/products.htm. -

Flattened Musk Turtle US Fish & Wildlife Service Recommended Sampling Protocol

Flattened Musk Turtle US Fish & Wildlife Service Recommended Sampling Protocol The flattened musk turtle (FMT) is a secretive cryptic species that is restricted to the Black Warrior River system, presently believed to occur upstream of the Bankhead Dam in portions of Blount, Cullman, Etowah, Fayette, Jefferson, Lawrence, Marshall, Tuscaloosa, Walker, and Winston Counties. It is seldom observed at the water surface because of its ability to augment its respiration subcutaneously, although it basks occasionally. It generally inhabits streams with drainage areas greater than 8 square miles, relatively clean substrates, and low turbidity, but may be found in suboptimal habitats. FMT may also be found in the lower reaches of smaller streams that flow into larger streams known to harbor FMT, and headwaters and margins of impounded lakes. Its primary food sources are macroinvertebrates, particularly snails, mussels, and insects. A general sampling protocol for this species should include the following considerations: 1. Determine if the aquatic habitat is suitable for this species. Optimal habitat is permanent oligotrophic streams from one to five feet deep containing abundant rocky ledges, slabs, logs, debris, and pools. Generally, aquatic habitats that lack flowing water, relatively clean substrates, benthic macroinvertebrates, and low turbidity are unsuitable. Adequate quantitative and photographic documentation of unsuitable habitat must be presented to the Daphne Field Office if a field survey that includes trapping is thought to be unnecessary by the consultant. 2. Visual searches in lieu of trapping are not acceptable unless a FMT is found and the consultant wishes to report that the FMT is present at a site. In this case, trapping would not be required unless the FMT must be held during construction activities. -

New Distributional Records of Freshwater Turtles

HTTPS://JOURNALS.KU.EDU/REPTILESANDAMPHIBIANSTABLE OF CONTENTS IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANSREPTILES • VOL &15, AMPHIBIANS NO 4 • DEC 2008 • 28(1):146–151189 • APR 2021 IRCF REPTILES & AMPHIBIANS CONSERVATION AND NATURAL HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS NewFEATURE Distributional ARTICLES Records of Freshwater . Chasing Bullsnakes (Pituophis catenifer sayi) in Wisconsin: TurtlesOn the Roadfrom to Understanding West-central the Ecology and Conservation of the Midwest’s GiantVeracruz, Serpent ...................... Joshua M. KapferMexico 190 . The Shared History of Treeboas (Corallus grenadensis) and Humans on Grenada: A Hypothetical Excursion ............................................................................................................................Robert W. Henderson 198 Víctor Vásquez-Cruz1, Erasmo Cazares-Hernández2, Arleth Reynoso-Martínez1, Alfonso Kelly-Hernández1, RESEARCH ARTICLESAxel Fuentes-Moreno3, and Felipe A. Lara-Hernández1 . 1PIMVS HerpetarioThe Texas Palancoatl,Horned Lizard Avenida in Central 19 andnúmero Western 5525, Texas Colonia ....................... Nueva Emily Esperanza, Henry, JasonCórdoba, Brewer, Veracruz, Krista Mougey, Mexico and ([email protected] Perry 204 ) 2Instituto Tecnológico. The KnightSuperior Anole de Zongolica.(Anolis equestris Colección) in Florida Científica ITSZ. Km 4, Carretera a la Compañía S/N, Tepetitlanapa, Zongolica, Veracruz. México 3Colegio de Postgraduados, ............................................. Campus Montecillo.Brian J. Carretera Camposano, México-Texcoco Kenneth -

Species Assessment for Eastern Musk Turtle

Species Status Assessment Class: Reptilia Family: Kinosternidae Scientific Name: Sternotherus odoratus Common Name: Eastern musk turtle (stinkpot) Species synopsis: Also known as the stinkpot, the eastern musk turtle emits a distinctive musky odor when threatened. It is highly aquatic, leaving the water infrequently, and moving awkwardly on land when it must. Occupied habitats include lakes, ponds, and rivers that have a muddy bottom substrate and little or no current. The musk turtle has a large distribution that extends across most of the eastern United States and into southern Canada, with a noticeable gap around higher elevation areas. New York is near the northern edge of the range. Musk turtles are common and apparently secure across the range with the exception of populations on the northern edge in Ontario and Quebec. Threats include shoreline development and the removal of submerged aquatic vegetation for recreational activities. I. Status a. Current and Legal Protected Status i. Federal ____Not Listed_______________________ Candidate? ___No_____ ii. New York ____SGCN_________________________________________________________ b. Natural Heritage Program Rank i. Global ____G5____________________________________________________________ ii. New York ____S5_____________________ Tracked by NYNHP? ___No____ Other Rank: IUCN – Least Concern COSEWIC – Special Concern Species of Low Priority (NEPARC 2010) 1 Status Discussion: Van Dijk (2011) refers to common musk turtle as a “very widespread, common, and adaptable species” that is “in no way threatened” despite some marginal populations of local conservation interest, including occurrences in Ontario and Quebec. Musk turtles are listed as Threatened in Canada where declines have been attributed to wetland destruction and shoreline alteration. It is also protected in Canada under the federal Species at Risk Act and is listed as a Specially Protected Reptile under the Ontario Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act. -

Latitudinal Variation in Egg and Clutch Size in Turtles

Latitudinal variation in egg and clutch size in turtles JOHNB. IVERSON,CHRISTINE P. BALGOOYEN,KATHY K. BYRD,AND KELLYK. LYDDAN Department of Biology, Earlham College, Richmond, IN 473 74, U.S. A. Received February 23, 1993 Accepted September 16, 1993 IVERSON,J.B., BALGOOYEN,C.P., BYRD,K.K., and LYDDAN,K.K. 1993. Latitudinal variation in egg and clutch size in turtles. Can. J. Zool. 71: 2448-2461. Reproductive and body size data from 169 populations of 146 species (56% of those recognized), 65 genera (75%), and 11 families (92%)of turtles were tabulated to test for latitudinal variation in egg and clutch size. Body-size-adjusted correla- tion analysis of all populations (as well as within most families) revealed (i) a significant negative relationship (r2 = 0.26) between latitude and egg size, (ii) a significant positive relationship (r2 = 0.2 1) between latitude and clutch size, and (iii) no relationship between latitude and clutch mass. Phylogenetic contrast analyses corroborated these patterns. Clutch size was also negatively correlated with egg size across all populations as well as within most families. We evaluate the applicability to turtles of hypotheses postulated to explain such latitudinal patterns for other vertebrate groups. The observed pattern may be the result of latitudinal variation in selection on egg size and (or) clutch size, as well as on the optimal trade-off between these two traits. IVERSON,J.B., BALGOOYEN,C.P., BYRD,K.K., et LYDDAN,K.K. 1993. Latitudinal variation in egg and clutch size in turtles. Can. J. Zool. 71 : 2448-2461. Les donnCes relatives h la reproduction et h la taille ont CtC enregistrkes chez 169 populations de 146 espkces (56% des espkces actuelles), 65 genres (75 %) et 11 familles (92%) de tomes; ces donnCes ont CtC organiskes en tableau afin d'Ctudier la variation latitudinale de la taille des oeufs et du nombre d'oeufs par couvCe. -

Genus: Sternotherus (Musk Turtles) - Darrell Senneke Copyright © 2003 World Chelonian Trust

Genus: Sternotherus (Musk Turtles) - Darrell Senneke Copyright © 2003 World Chelonian Trust. All rights reserved Sternotherus carinatus - Razor-backed Musk Turtle Sternotherus depressus - Flattened Musk Turtle Sternotherus minor - Loggerhead Musk Turtle Sternotherus minor peltifer - Stripe-neck Musk Turtle Sternotherus odoratus - Common Musk Turtle This care sheet is intended only to cover the general care of these species. Further research to best develop a maintenance plan for whichever species you are caring for is essential.. Many taxonomists often combine genus Sternotherus with Kinosternon as sub- genera of the Family Kinosternidae. While these animals share many of the same habitats, features and care requirements, for the purpose of this care sheet they will be treated as a full Genus. Musk turtles can be found from the Canadian Southern border to Florida and West to the Rocky Mountains. These species are more carnivorous than most turtles with a natural diet that relies heavily on fish, snails, crustaceans and insects. While the Razor-back Musk turtle can attain a size of 15 cm. (6 inches), the much more commonly seen Stinkpot only attains 8 - 10 cm (3 - 4 inches) maximum. Present knowledge and technology make Musk turtles easily maintained animals as long as a person is willing to provide some basic requirements. Thanks to the success that breeders are having with these species it is now possible to purchase many of these species as hatchlings from captive born stock. Some of the species are threatened or endangered in nature, do not remove these animals from the wild. HOUSING MUSK TURTLES INDOORS - The most useful form of indoor accommodation for Sternotherus consists of an aquarium. -

Kinosternon Subrubrum (Bonnaterre 1789) – Eastern Mud Turtle

Conservation Biology of Freshwater Turtles and Tortoises: A Compilation ProjectKinosternidae of the IUCN SSC — KinosternonTortoise and Freshwater subrubrum Turtle Specialist Group 101.1 A.G.J. Rhodin, J.B. Iverson, P.P. van Dijk, K.A. Buhlmann, P.C.H. Pritchard, and R.A. Mittermeier, Eds. Chelonian Research Monographs (ISSN 1088-7105) No. 5, doi:10.3854/crm.5.101.subrubrum.v1.2017 © 2017 by Chelonian Research Foundation and Turtle Conservancy • Published 17 September 2017 Kinosternon subrubrum (Bonnaterre 1789) – Eastern Mud Turtle WALTER E. MESHAKA, JR.1, J. WHITFIELD GIBBONS2, DANIEL F. HUGHES3, MICHAEL W. KLEMENS4, AND JOHN B. IVERSON5 1State Museum of Pennsylvania, 300 North Street, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania 17120 USA [[email protected]]; 2Savannah River Ecology Lab, Drawer E, Aiken, South Carolina 29802 USA [[email protected]]; 3University of Texas at El Paso, El Paso, Texas 79968 USA [[email protected]]; 4Department of Herpetology, American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West at 79th Street, New York, New York 10024 USA [[email protected]]; 5Department of Biology, Earlham College, Richmond, Indiana 47374 USA [[email protected]] SUMMARY. — The Eastern Mud Turtle, Kinosternon subrubrum (Family Kinosternidae), is a small (carapace length 85 to 120 mm) polytypic species of the eastern and central United States. All three historically recognized subspecies (K. s. subrubrum, K. s. steindachneri, and K. s. hippocrepis) are semi-aquatic turtles that inhabit much of the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf Coastal Plains. The Florida taxon (K. s. steindachneri) appears to represent a distinct species, but we continue to treat it as a subspecies for the purposes of this account.