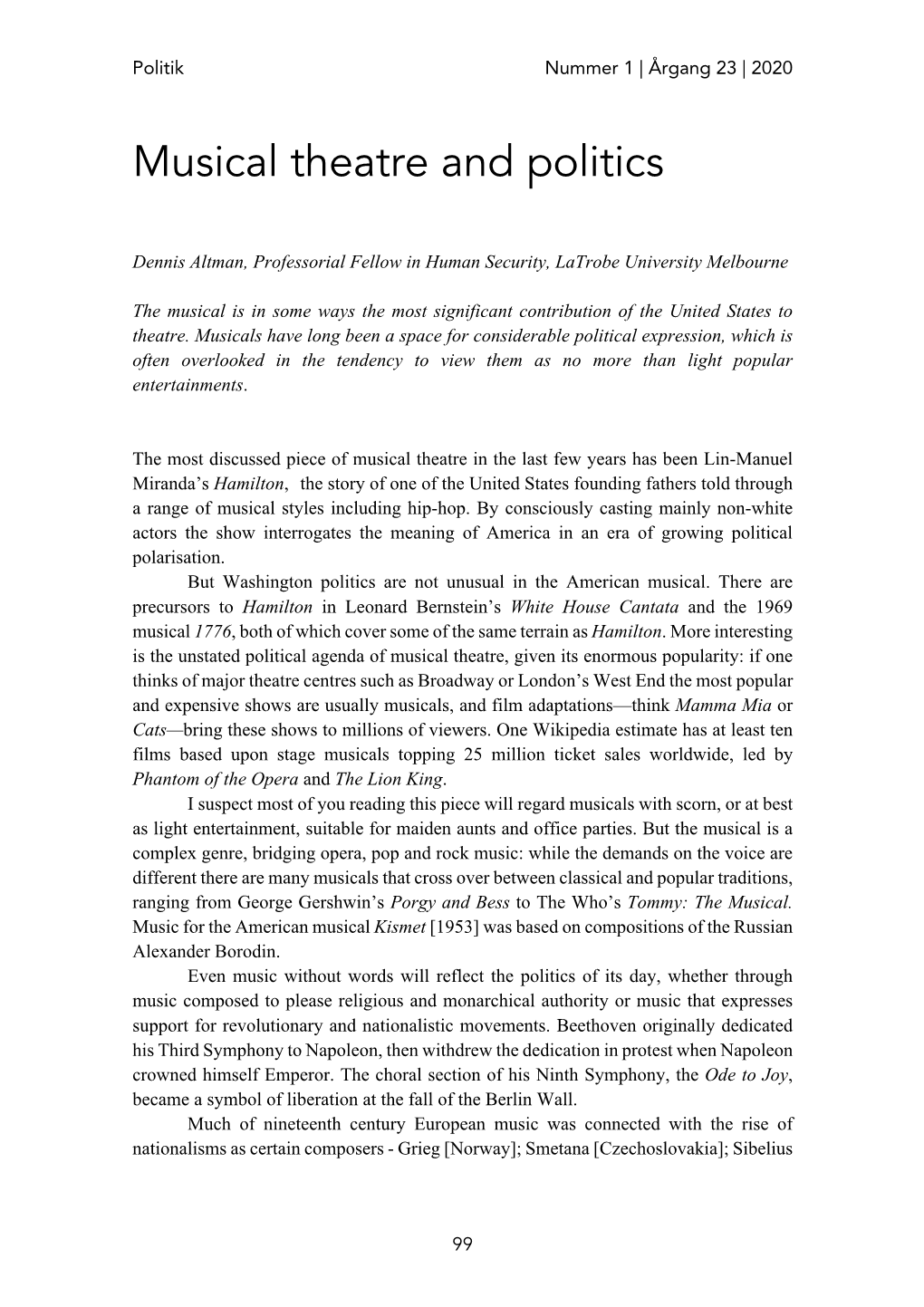

Musical Theatre and Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 1 & 3, 2021 Walt Disney Theater

April 1 & 3, 2021 Walt Disney Theater FAIRWINDS GROWS MY MONEY SO I CAN GROW MY BUSINESS. Get the freedom to go further. Insured by NCUA. OPERA-2646-02/092719 Opera Orlando’s Carmen On the MainStage at Dr. Phillips Center | April 2021 Dear friends, Carmen is finally here! Although many plans have changed over the course of the past year, we have always had our sights set on Carmen, not just because of its incredible music and compelling story but more because of the unique setting and concept of this production in particular - 1960s Haiti. So why transport Carmen and her friends from 1820s Seville to 1960s Haiti? Well, it all just seemed to make sense, for Orando, that is. We have a vibrant and growing Haitian-American community in Central Florida, and Creole is actually the third most commonly spoken language in the state of Florida. Given that Creole derives from French, and given the African- Carribean influences already present in Carmen, setting Carmen in Haiti was a natural fit and a great way for us to celebrate Haitian culture and influence in our own community. We were excited to partner with the Greater Haitian American Chamber of Commerce for this production and connect with Haitian-American artists, choreographers, and academics. Since Carmen is a tale of survival against all odds, we wanted to find a particularly tumultuous time in Haiti’s history to make things extra difficult for our heroine, and setting the work in the 1960s under the despotic rule of Francois Duvalier (aka Papa Doc) certainly raised the stakes. -

The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui

Classic Stage Company JOHN DOYLE, Artistic Director TONI MARIE DAVIS, Chief Operating Officer/GM presents THE RESISTIBLE RISE OF ARTURO UI BY BERTOLT BRECHT TRANSLATED BY GEORGE TABORI with GEORGE ABUD, EDDIE COOPER, ELIZABETH A. DAVIS, RAÚL ESPARZA, CHRISTOPHER GURR, OMOZÉ IDEHENRE, MAHIRA KAKKAR, THOM SESMA Costume Design Lighting Design Sound Design ANN HOULD-WARD JANE COX MATT STINE TESS JAMES Associate Scenic Design Associate Costume Design Associate Sound Design DAVID L. ARSENAULT AMY PRICE AJ SURASKY-YSASI Casting Press Representative Production Stage Manager TELSEY + COMPANY BLAKE ZIDELL AND ASSOCIATES BERNITA ROBINSON ADAM CALDWELL, CSA WILLIAM CANTLER, CSA Assistant Stage Manager KARYN CASL, CSA JESSICA FLEISCHMAN DIRECTED AND DESIGNED BY JOHN DOYLE Cast in alphabetical order Clark / Ragg.............................................................................GEORGE ABUD Roma..........................................................................................EDDIE COOPER Giri......................................................................................ELIZABETH A. DAVIS Arturo Ui....................................................................................RAÚL ESPARZA Dogsborough / Dullfeet..........................................CHRISTOPHER GURR O’Casey / Betty Dullfeet.............................................OMOZÉ IDEHENRE Flake / Dockdaisy...............................................................MAHIRA KAKKAR Givola............................................................................................THOM -

• Interview with Lorenzo Tucker. Remembering Dorothy Dandridge. • Vonetta Mcgee • the Blaxploitation Era • Paul Robeson •

• Interview with Lorenzo Tucker. Remembering Dorothy Dandridge. • Vonetta McGee • The Blaxploitation Era • Paul Robeson •. m Vol. 4, No.2 Spring 1988 ,$2.50 Co-produced with the Black Film Institute of the University of the District of Columbia .,.... ~. .# • ...-. .~ , .' \ r . t .• ~ . ·'t I !JJIII JlIf8€ LA~ ~N / Ul/ll /lOr&£ LAlE 1\6fJt1~ I WIL/, ,.,Dr 8~ tATE /lfVll" I h/ILl kif /J£ tlf1E M/tl# / wlU ~t11' BE 1II~ fr4lt11 I k/Ilt- /V6f Ie tJ]1f. 1t6/tlfV _ I WILL No~ ~'% .,~. "o~ ~/~-_/~ This is the Spring 1988 issue of der which we mail the magazine, the Black Fzlm Review. You're getting it U.S. Postal Service will not forward co- ~~~~~ some time in mid 1988, which means pies, even ifyou've told them your new',: - we're almost on schedule. - address. You need to tell us as well, be- \ Thank you for keeping faith with cause the Postal Service charges us to tell us. We're going to do our best not to us where you've gone. be late. Ever again. Third: Why not buy a Black Fzlm Without your support, Black Fzlm Review T-shirt? They're only $8. They Review could not have evolved from a come in black or dark blue, with the two-page photocopied newsletter into logo in white lettering. We've got lots the glossy magazine it is today. We need of them, in small, medium, large, and your continued support. extra-large sizes. First: You can tell ifyour subscrip And, finally, why not make a con tion is about to lapse by comparing the tribution to Sojourner Productions, Inc., last line of your mailing label with the the non-profit, tax-exempt corporation issue date on the front cover. -

THE TRAGEDY of CARMEN by PETER BROOK DONALD and DONNA BAUMGARTNER Presnting Title Sponsor

March 13, 15, 21 & 22, 2020 Wilson Theater at Vogel Hall Marcus Performing Arts Center ROBERT SOBCZAK Presnting Title Sponsor THE TRAGEDY OF CARMEN BY PETER BROOK DONALD AND DONNA BAUMGARTNER Presnting Title Sponsor VERDI’S MACBETH May 29 at 7:30pm | May 31 at 2:30pm Marcus Performing Arts Center Call 414-291-5700 x 224 or www.florentineopera.org THE SEASON OF THE 2020 2 0 2 1 ENSEMBLE THE TRAGEDY OF CARMEN BY PETER BROOK Photo: Cory Weaver Cory Photo: THE TRAGEDY OF CARMEN BY PETER BROOK PROGRAM INFORMATION 07 From the General Director & CEO 09 From the Board President 10 Donor Spotlights 11 In Memorium 14 Credits 15 Cast 17 Synopsis 18 Program Notes 20 Director’s Notes 22 Conductor, Christopher Rountree 23 Stage Director, Eugenia Arsenis 24 The Anello Society 28 Artist Biographies 34 Musicians 38 Board of Directors 39 Lifetime Donors 40 Commemorative Gifts 41 Annual Donors 48 Florentine Opera Staff Cover Photo: Brianne Sura Photo Credit: Becca Kames Photo: Cory Weaver Cory Photo: FLORENTINE OPERA COMPANY 5 GENERAL INFORMATION Please make sure all cellular phones, pagers GROUP RATES: and watch alarms are turned off prior to the Groups of 10 or more are eligible for special performance. No photography or videography discounts off regular single ticket prices for is allowed by audience members during the selected performances. For more information, performance. call (414) 291-5700, ext. 224. LATE SEATING: ACCESSIBILITY: Guests arriving late will be seated at a suitable Wheelchair seating is available on the main pause in the performance. Please be advised floor in Vogel Hall and Uihlein Hall. -

2019 Lucille Lortel Awards Nominations

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Chris Kanarick [email protected] O: 646.893.4777 34TH ANNUAL LUCILLE LORTEL AWARDS NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED MULTIPLE EMMY AWARD-WINNER, PERFORMER, COMEDIAN – WAYNE BRADY – TO HOST THE CEREMONY Carmen Jones and Rags Parkland Sings The Songs Of The Future tie for most nominations with six each – including Outstanding Revival and Outstanding Musical, respectively Current Broadway productions Be More Chill and What The Constitution Means To Me earn nominations for their Off-Broadway stints – including Outstanding Musical and Outstanding Play Among the many notable nominees are playwrights Jeremy O. Harris and Phoebe Waller-Bridge and performers Joel Grey, George Salazar, Mare Winningham, and Jackie Hoffman Major studios debut on the Off-Broadway theatre scene with Annapurna Theatre as a producer on FLEABAG and Amazon’s Audible producing Girls & Boys, performed by Carey Mulligan New York, NY (April 3, 2019) – The Off-Broadway League today announced nominations in 19 categories – and bestowed one special award – for the 34th Annual Lucille Lortel Awards for Outstanding Achievement Off- Broadway. The Awards will be handed out on Sunday, May 5, 2019 at NYU Skirball Center for Performing Arts, beginning at 7:00pm EST. The Lucille Lortel Awards are produced by the Off-Broadway League by special arrangement with the Lucille Lortel Theatre Foundation. Additional support is provided by TDF. Beloved and celebrated entertainer, Wayne Brady, will emcee the ceremony. Leading the nominations this year are: Carmen Jones, with six nominations including one for Outstanding Revival and for John Doyle’s direction, as well as in three of the four performance categories; Ars Nova’s Rags Parkland Sings The Songs Of The Future also earned six nominations, including Outstanding Musical and Lead Actress and Actor in a Musical; current social media phenom Be More Chill received four nominations including Outstanding Musical, Outstanding Featured Actor in a Musical for George Salazar, and Outstanding Featured Actress in a Musical for Stephanie Hsu. -

BALLOT Fairview

Friends of AUDELCO AUDELCO (Audience Development Committee, Inc.) List of Nominated Plays AUDELCO was established and incorporated in 1973 to In order to keep abreast of your support of professional generate more recognition, understanding and awareness Black theatre, we request that you check the plays listed of the arts in African-American communities; to provide below that you have seen. All listed plays have better public relations and to build new audiences for non- nominations in one or more categories. profit theatre and dance companies. A Small Oak Tree Runs Red You receive discounts to some of your favorite Off and A Soldier’s Play Off-Off Broadway theatres when you attend theatre and AUDELCO Ain’t MisBehavin’ dance productions as a “Friend of AUDELCO.” (Audience Development Committee, Inc.) Antigone Carmen Jones At informal gatherings, “Friends of AUDELCO” meet 2018 Cross That River: A Tale of the Black West and interact with others who share an interest in Black Theatre and Dance. BALLOT Fairview Feeding the Dragon “Friends of AUDELCO” receive INTERMISSION, our Freight: The Five Incarnations of Abel Green In-House newsletter. Friends are kept abreast of current NOMINEES FOR THE th Gypsy activities through newsletter updates. 46 ANNUAL VIVIAN ROBINSON Harriet’s Return AUDELCO RECOGNITION AWARDS He Brought Her Heart Back in a Box On the third Monday of November, AUDELCO presents FOR EXCELLENCE IN BLACK THEATRE Jerry Springer: The Opera the annual AUDELCO Awards, recognizing and 2017 – 2018 THEATRE SEASON Jesus Hopped the ‘A’ Train honoring Excellence in Black Theatre. Josephine Josh: The Black Babe Ruth Your contribution enables you to vote for productions and Presented by Little Rock performers of your choice. -

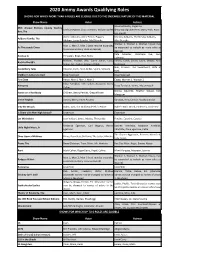

2020 Jimmy Awards Qualifying Roles

2020 Jimmy Awards Qualifying Roles SHOWS FOR WHICH MORE THAN 6 ROLES ARE ELIGIBLE DUE TO THE ENSEMBLE NATURE OF THE MATERIAL Show Name Actor Actress Olive Ostrovsky, Logainne 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Leaf Coneybear, Chip Tolentino, William Barfee Shwartzandgrubenierre, Marcy Park, Rona Bee, The Lisa Peretti Gomez Addams, Uncle Fester, Pugsley Morticia Addams, Wednesday Addams, Addams Family, The Addams, Lucas Beineke, Mal Beineke Alice Beineke Woman 1, Woman 2, Woman 3 (cast may Man 1, Man 2, Man 3 (cast may be expanded As Thousands Cheer be expanded to include as many roles as to include as many roles as desired) desired) Kate Monster, Christmas Eve, Gary Avenue Q Princeton, Brian, Rod, Nicky Coleman Michael, Feargal, Billy, Corey Junior, Corey Tiffany, Cyndi, Eileen, Laura, Debbie, Miss Back to the 80's Senior, Mr. Cocker, Featured Male Brannigan Nun, Prioress, The Sweetheart, Wife of Canterbury Tales Chaucer, Clerk, Host, Miller, Squire, Steward Bath Children's Letters to God Ensemble Cast Ensemble Cast First Date Aaron, Man 1, Man 2, Man 3 Casey, Woman 1, Woman 2 Edna Turnblad, Link Larken, Seaweed, Corny Hairspray Tracy Turnblad, Velma, Motormouth Collins Norma Valverde, Heather Stovall, Kelli Hands on a Hardbody JD Drew, Benny Perkins, Greg Wilhote Mangrum In the Heights Usnavi, Benny, Kevin Rosario Vanessa, Nina, Camila, Abuela Claudia Into the Woods Baker, Jack, The Wolf/Cinderella's Prince Baker's Wife, Witch, Cinderella, Little Red Is There Life After High School? Ensemble Ensemble Les Misérables Jean Valjean, Javert, Marius, Thenardier Fantine, Eponine, Cosette Frederick Egerman, Carl Magnus, Henrik Desiree Armfeldt, Madame Armfeldt, Little Night Music, A Egerman Charlotte, Anne Egerman, Petra The Queen Aggravain, Princess Winnifred, Once Upon a Mattress Prince Dauntless, Sir Harry, The Jester, Minstrel Lady Larkin Prom, The Barry Glickman, Trent Oliver, Mr. -

Carmen Jones Audition

CARMEN JONES By Oscar Hammerstein II Based on the Opera Carmen by Georges Bizet Directed by Thomas-Whit Ellis AUDITION INFORMATION WHAT IS THE PLAY ABOUT? Carmen Jones is an African American musical based on the opera Carmen. It is not the opera Carmen, it does not use operatic, “trained voice” stylized singing, although trained voices are encouraged to audition. It is about the lead character, who through her charm and other attributes, drives men crazy with love for her. She is her own woman and does not let any man dictate her terms of whom or when to love. She’s much like Nola Darling, in the Spike Lee film She’s Got to Have It. The play opens with Joe, a military recruit soon to be a black Air Force pilot, falling for her and quickly ditching his broken hearted, high school sweetheart for Carmen. In the meantime, Carmen soon gets into a brawl and kills another woman who also thinks she’s all that. This promptly lands Carmen in jail. Joe is assigned to escort her into town to stand trial. Along the way, he is overwhelmed by “charms,” sets her free, abandons his life and career to become a co-fugitive with her. She soon grows grows bored with his clinginess and meets the heavy weight champion of the world, who is passing through town with his entourage. He falls for her and invites her to travel with him to his next series of fights. We then trace the set of dramas that take place with Joe still pining after her, his old girlfriend pining after him, along with other murders, misdeeds and problems. -

2017 NHSMTA Qualifying Roles SHOWS for WHICH MORE THAN 6 ROLES ARE ELIGIBLE DUE to the ENSEMBLE NATURE of the MATERIAL Show Name Actor Actress Rights House

2017 NHSMTA Qualifying Roles SHOWS FOR WHICH MORE THAN 6 ROLES ARE ELIGIBLE DUE TO THE ENSEMBLE NATURE OF THE MATERIAL Show Name Actor Actress Rights House 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Olive Ostrovsky, Logainne Shwartzandgrubenierre, Leaf Coneybear, Chip Tolentino, William Barfee Bee, The Marcy Park, Rona Lisa Peretti MTI Man 1, Man 2, Man 3 (cast may be expanded Woman 1, Woman 2, Woman 3 (cast may be As Thousands Cheer to include as many roles as desired) expanded to include as many roles as desired) R&H Avenue Q Princeton, Brian, Rod, Nicky Kate Monster, Christmas Eve, Gary Coleman MTI Canterbury Tales Chaucer, Clerk, Host, Miller, Squire, Steward Nun, Prioress, The Sweetheart, Wife of Bath MTI Children's Letters to God Ensemble Cast Ensemble Cast SFI Hua Mulan, Pocahontas, Princess Badroulbadour, Disenchanted N/A Belle, Little Mermaid, Snow White, Rapunzel TRW First Date Aaron, Man 1, Man 2, Man 3 Casey, Woman 1, Woman 2 R&H Hands on a Hardbody JD Drew, Benny Perkins, Greg Wilhote Norma Valverde, Heather Stovall, Kelli Mangrum SFI Is There Life After High School? Ensemble Ensemble SFI Les Misérables Jean Valjean, Javert, Marius, Thenardier Fantine, Eponine, Cosette MTI Prince Dauntless, Sir Harry, The King, The Once Upon a Mattress The Queen Aggravain, Princess Winnifred, Lady Larkin Jester, Minstrel R&H Rent Mark Cohen, Roger Davis, Angel, Collins Mimi Marquez, Maureen, Joanne MTI Man 1, Man 2, Man 3 (cast may be expanded Woman 1, Woman 2, Woman 3 (cast may be Rodgers & Hart to include as many roles as desired) expanded to include as many roles as desired) R&H Ken, Adrian, Frederick, Victor, Michael Brenda, Pattie, DeLee, B.J. -

Dancing Dreams: Performing American Identities in Postwar Hollywood Musicals, 1944-1958

Dancing Dreams: Performing American Identities in Postwar Hollywood Musicals, 1944-1958 Pamella R. Lach A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Peter G. Filene John F. Kasson Robert C. Allen Jerma Jackson William Ferris ©2007 Pamella R. Lach ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Pamella R. Lach Dancing Dreams: Performing American Identities in Postwar Hollywood Musicals, 1944-1958 (Under the direction of Peter G. Filene) With the pressures of the dawning Cold War, postwar Americans struggled to find a balance between conformity and authentic individualism. Although musical motion pictures appeared conservative, seemingly touting traditional gender roles and championing American democratic values, song-and-dance numbers (spectacles) actually functioned as sites of release for filmmakers, actors, and moviegoers. Spectacles, which film censors and red- baiting politicians considered little more than harmless entertainment and indirect forms of expression, were the least regulated aspects of musicals. These scenes provided relatively safe spaces for actors to play with and defy, but also reify, social expectations. Spectacles were also sites of resistance for performers, who relied on their voices and bodies— sometimes at odds with each other—to reclaim power that was denied them either by social strictures or an oppressive studio system. Dancing Dreams is a series of case studies about the role of spectacle—literal dances but also spectacles of discourse, nostalgia, stardom, and race—in inspiring Americans to find forms of individual self-expression with the potential to challenge prevailing norms. -

Elmar Plppfl CORNELL POWER Extta EXCLUSIVE SHOWING Tewiohmtwnßo.Hu Fyssn|L the DARK W Ns*, for I Sn •«» • N.Re

THE EVENING STAB, Washington, D. C. v B-18 ** wawwt. j**t;*»Tn. iass The Passing Show I 'Carmen Jones'a Lethal Siren ¦ I" THIS TRUTH BEHIND THE GREAT liiMusical at Capitol I THE By Smf Cormody Hollywood may have lagged in getting around to “Carmen Jones," a Broadway musical hit of a decade ago. but there is *2,500,0009 9 BOSTON ROBBERY? no.-dearth of vivacity in tne film version which opened today at Loew*s Capitol. A superb Negro cast headed by Dorothy Dandridge. Harry Th« law «»t aura ItkMw Belafonte and Peart Bailey acts/ sings and dances the tale of the •‘CARMEN JONES.” A Tw«tl«th- .. who masterminded the robbery* recklessly high spirited heroine Century-Foi picture, produced and directed b» Otto Prembwer. book upa Hr'’' -f||j Vk' upon lyrics by Oscar Hammer stein 11. screen- in the production based Hurry music by But th *cro °k h<>d an a|>Mt adaptation pley to Kldncr. Oeortee ' Oscar Hammerstein’s Bluet. At tbe Cupltol. HK Mr of Bizet’s “Carmen.” The spon- When the struck, soring studio is 20th Century- —mifflßßHHjVY}i sans Pox which has had an admirably VVV\ He was talk!ns to a cop ! extravagant idea of how this sort safe of thing should be done. Dink HickStevurt entire careers * main, the treatment whose In the Myrt TXulunp Omni] here follows the Hammersteln X 4.Y was linked with his. original and the talented Negro iu&y Hunt Lynn YaX performers clearly relish the Trnlaer DcForeet Corun end the voice* el _ . -

NPS Form 10 900 OMB No

NPS Form 10-900-b (Rev. 01/2009) OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (formerly 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items Yes New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic Resources Associated with African Americans in Los Angeles B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronoligical period for each.) Settlement Patterns, 1890s – 1958 Labor and Employment, 1900 – 1958 Community Development, 1872-1958 Civic Engagement, 1870 – 1958 Entertainment and Culture, 1915-1958 C. Form Prepared by name/title Teresa Grimes, Senior Architectural Historian organization Christopher A. Joseph & Associates date 12/31/08 street & number 523 W. 6th Street, Suite 1134 telephone 213-417-4400 city or town Los Angeles state CA zip code 90014 e-mail [email protected] D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR 60 and the Secretary of the Interior’s Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation.