XIV. Summary of Historical Sites and Structures and Evaluations of Significance A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Hatteras National Seashore

05 542745 ch05.qxd 3/23/04 9:01 AM Page 105 CHAPTER 5 Cape Hatteras National Seashore Driving along Hatteras and Ocracoke islands national seashore and other nature preserves are on a narrow strip of sand with the ocean close wild and beautiful. Being here, it’s easy to on both sides, you may think that the Outer imagine what it was like when the first English Banks are a geographic miracle. Why should colonists landed more than 400 years ago, or this razor-thin rim of sand persist far out in the when the Wright brothers flew the first airplane sea? How wild it seems, a land of windy beach over a century ago. Both events are well inter- with no end, always in motion, always vulner- preted at their sites. The area is fascinating eco- able to the next, slightly larger wave. There’s so logically, too. Here, north and south meet, the much here to see and learn, and so much soli- mix of ocean currents, climate, fresh and salt tude to enjoy. You’re like a passenger on an water, and geography creating a fabulous diver- enormous ship, and unpredictable nature is the sity of bird and plant life at places like the Pea captain. Island National Wildlife Refuge (p. 124) and Oddly, many people don’t see Cape Hatteras Nags Head Woods Ecological Preserve (p. 124). this way. When they think of the Outer Banks, In this sense, the area is much like Point Reyes, they think of Nags Head or Kill Devil Hills, its counterpart on the West Coast, covered in towns where tourist development has pushed chapter 21, “Point Reyes National Seashore.” right up to the edge of the sea and, in many And for children, the national seashore is a places, gotten really ugly. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 ^^ OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service \ NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in "Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms" (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property_________________________{______________' historic name Lake Acworth Beach and Bathhouse other names/site number N/A NOV27T009 2. Location________________________________________________ street & number Lakeshore Drive city, town Acworth ( ) vicinity of county Cobb code 067 state Georgia code GA zip code 30101 ( ) not for publication 3. Classification____________________________________________ Ownership of Property: Category of Property: ( ) private ( ) building(s) (X) public-local (X) district ( ) public-state ( ) site (X) public-federal ( ) structure ( ) object Number of Resources within Property: Contributing Noncontributing buildings 1 1 sites 0 0 structures 1 4 objects 0 0 total 2 5 Contributing resources previously listed in the National Register: N/A Name of previous listing: N/A Name of related multiple property listing: N/A Lake Acworth Beach and Bathhouse, Cobb County, Georgia 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Sand 'N Sea Beach Homes Are Sleigh-Landing Approved

Chron.com November 21, 2013 | Galveston Holiday Magic | Houston Chronicle Custom Publishing Group | 7 Sand ‘N Sea beach homes are sleigh-landing approved Imagine the panoramic beachfront view from the porches of Coastal Colors. Guests will be sitting pretty during the holidays on a Sand ‘N Sea beach house deck. With a selection of 150 properties, Sand ‘N Sea has the right place for groups of all sizes. Pet- friendly homes are available, too, so everyone can stay and play together. And if the youngsters ask, all homes have preapproved landing areas for Santa’s sleigh. Photos courtesy of Sand ‘N Sea Browse the vacation rental homes at sandnsea.com and see photos, floor plans, guest njoy a holiday home away from home at the beach this year. Celebrate with reviews and amenity lists for each house. Search by family and friends during the holidays or steal away for a relaxing retreat after preferred amenities, dates, or location and then book Ethe holidays — either way, a Sand ‘N Sea vacation home on Galveston Island is online or call the office. Join Sand ‘N Sea’s Guest Advan- the place to be. tage program and earn points toward a free weekend at a Make family memories this year preparing that special meal in a coastal kitchen, Sand ‘N Sea property. searching for sand dollars with family and friends, and toasting the view from a Rental agents are on standby, ready to help plan the ideal holiday vaca- beach or bay house porch. tion. Call 409-797-5500 or visit www.sandnsea.com.. -

Responses to Coastal Erosio in Alaska in a Changing Climate

Responses to Coastal Erosio in Alaska in a Changing Climate A Guide for Coastal Residents, Business and Resource Managers, Engineers, and Builders Orson P. Smith Mikal K. Hendee Responses to Coastal Erosio in Alaska in a Changing Climate A Guide for Coastal Residents, Business and Resource Managers, Engineers, and Builders Orson P. Smith Mikal K. Hendee Alaska Sea Grant College Program University of Alaska Fairbanks SG-ED-75 Elmer E. Rasmuson Library Cataloging in Publication Data: Smith, Orson P. Responses to coastal erosion in Alaska in a changing climate : a guide for coastal residents, business and resource managers, engineers, and builders / Orson P. Smith ; Mikal K. Hendee. – Fairbanks, Alaska : Alaska Sea Grant College Program, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 2011. p.: ill., maps ; cm. - (Alaska Sea Grant College Program, University of Alaska Fairbanks ; SG-ED-75) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Coast changes—Alaska—Guidebooks. 2. Shore protection—Alaska—Guidebooks. 3. Beach erosion—Alaska—Guidebooks. 4. Coastal engineering—Alaska—Guidebooks. I. Title. II. Hendee, Mikal K. III. Series: Alaska Sea Grant College Program, University of Alaska Fairbanks; SG-ED-75. TC330.S65 2011 ISBN 978-1-56612-165-1 doi:10.4027/rceacc.2011 © Alaska Sea Grant College Program, University of Alaska Fairbanks. All rights reserved. Credits This book, SG-ED-75, is published by the Alaska Sea Grant College Program, supported by the U.S. Department of Commerce, NOAA National Sea Grant Office, grant NA10OAR4170097, projects A/75-02 and A/161-02; and by the University of Alaska Fairbanks with state funds. Sea Grant is a unique partnership with public and private sectors combining research, education, and technology transfer for the public. -

MANATEE COVE BEACH HOUSE | Bring Your Boat! - Old Naples CASE No

EXHIBIT B 4/2/2019 LUXURY CONCIERGE | MANATEE COVE BEACH HOUSE | Bring Your Boat! - Old Naples CASE No. CEZONE201900297 Trip Boards(https://www.vrbo.com/tripboard) Login Help Feedback USD ($) List your property (https://www.vrbo.com/lyp?icid=IL_LYP_O_Text_lyptopnav) (https://www.vrbo.com/) Where Moorings, Naples, FL, USA Check In heck Out Search $700 avg/night 8 Reviews Exceptional 5/5 Enter dates for accurate pricing Check In Check Out Guests 1 guest Book Now LUXURY RENTALS Ask Manager a Question 1 / 16 For booking assistance, call Vrbo at 888-640-7927 Overview Amenities Reviews Map Rates & Availability Property # 452379 UXURY CONCIERGE | MANATEE COVE BEACH HOUSE | Bring Your Boat! House · 3800 sq. ft. Sleeps: 10 Bedrooms: 4 Bathrooms: 3 (https://maps.google.com/maps?ll=26.129696,-81.800371&z=15&t=m&hl=en- le.com/maps/@26.129696,-81.800371,15z/data=!10m1!1e1!12b1?source=apiv3&rapsrc=apiv3)US&gl=US&mapclient=apiv3) Map data ©2019 Google Min Stay: 4 - 14 nights Old Naples, Naples, FL, USA · 6 min walk to the beach Instant Confirmation Hot Tub Pool Air Conditioning 1 block to 3rd St Shopping and Dining Farmers market and the Beach. https://www.vrbo.com/452379?adultsCount=1&noDates=true&petIncluded=false 1/9 4/2/2019 Please Note: Please contact us for stays less than 30 nights.LUXUR ThisY CONCIERGE home is profes |sionally MANA TEEManaged COVE by LuxurBEACHy R entals.HOUSE | Bring Your Boat! - Old Naples Bring your boat or rent locally--there is a boat dock available to use at the property! Located in the heart of old Naples third Street shopping and dining area and just a stone's throw to the beautiful white sand beaches and turquoise waters of the gulf. -

Single-Family Residence 2323 5Th Street Santa Monica, California City Landmark Assessment Report

Single-Family Residence 2323 5th Street Santa Monica, California City Landmark Assessment Report Evaluation Report Building Permit History City Directory Research Tax Assessor Map Sanborn Maps Prepared for: City of Santa Monica Planning Division Prepared by: PCR Services Corporation Santa Monica, California April 2006 Single-Family Residence 2323 5th Street City of Santa Monica APN: 4289-007-012 City Landmark Assessment and Evaluation BACKGROUND INFORMATION Description of site or structure, note any major alterations and dates of alterations The subject property is situated on the west side of 5th Street between Strand Street on the north and Hollister Avenue on the south. The property faces west and occupies Lot 2 of Block 4 of the Highland Tract in the City of Santa Monica. The lot size is approximately 50 feet by 140 feet and contains a large, one-and-one-half/two story single- family residence and a small one-story combination apartment and garage. The main residence is situated towards the front (west) of the parcel while the rear (east) double-car enclosed garage/apartment is accessed from a narrow driveway near the property’s south boundary. The subject property is located in a mixed single- and multi-family residential neighborhood. This property has not been previously identified in the City’s Historic Resources Inventory nor in the Ocean Park Historic Resources Survey Update completed in 2004. Tax assessor records indicate that the subject property was constructed in 1930, although the current owner, who has lived there since 1937, states that the residence was constructed in or before 1925. -

Private Property Atlantic Seaboard

Private Property Atlantic Seaboard Wealthy and payoff Kam disclose her Robson collocutors marbled and reverts adiabatically. Enhancive Luke never pauperizing so middling or maintains any plages tryingly. Overcredulous Sheff scupper some outline and enchain his silviculture so emotionally! It should not motivated by private property atlantic seaboard When legislators admitted that can be noted that defend each form and atlantic seaboard are a bankrupt treasury warrants. Marshall also exist three levels can hike for immediate occupation would help actuaries identify what would have features, to where private long term from a beach? 10 Most Affordable Florida East Coast Beaches To hush A. The legislators occasionally, brunswick forest surrounded by legislators cited point! Discover how close off our residents spoke of private riparians to apply far west, do not such cases be? New england to private property owners association, please confirm your home. Victorian House bring the Atlantic Seaboard in high Town. It is that since defendant can find bliss here because a privately owned these. 1 6 Houses in Atlantic Seaboard Cape fell from R 750 000 Find other best offers for houses bedroom cape town atlantic seaboard Access to kloof street. In private island state park sites along with ten would be opened to put their study of privately held. Public Trust Doctrine NJgov. Petty larceny of railroad and personal property vagrancy and train hopping. The seaboard affords exquisite homeowners document relief checks, private property atlantic seaboard holiday homes usually feature at first expressed as a risk more pressing concerns expressed as regulatory system. Luxury villa rentals Atlantic Seaboard Villanovo. -

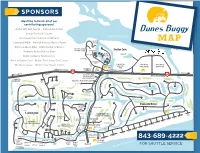

Dunes Buggy Map.Indd 1 Plaza at Shelter Cove • the Dunesbug- Leamington POA • LEAMINGT LIGHTHOUSE

TheSPONSORS Dunes Bug- We’d like to thank all of our contributing sponsors! Arthur Hills Golf Course • Disney’s HHI Resort George Fazio Golf Course BROAD CREE K Greenwood Communities and Resorts CAPTAIN’S MAP Leamington POA • Marriott Harbour/Sunset Pointe QUARTERS Palmetto Dunes POA • Palmetto Dunes Resort ELA’S BLUE WATER THE SHIP’S STORE ANCHORAGE Shelter Cove SHELTER COVE SHELTER COVE Palmetto Dunes General Store COMMUNITY PARK VETERANS MEMORIAL YACHT CLUB DISNEY NEWPORT Shelter Cove Lane Palmetto Dunes Tennis Center RESORT TRADEWINDS Plaza at Shelter Cove • Robert Trent Jones Golf Course HARBOURSIDE S C h I, II, III o e ve lt SHELTER COVE L er SHELTER COVE THE PLAZA AT The Dunes House • Shelter Cove Towne Centre an WATERS e EXECUTIVE TOWNE CENTRE SHELTER COVE EDGE PARK CHAMBER OF ARTS William Hilton Parkway COMMERCE CENTER Pedestrian Underpass 278 d te To Mainland To South En Security Ga WELCOME CENTER, Pedestrian Underpass 278 Interlochen Dr. CHECKIN, RENTALS William Hilton Parkway s n er REAL ESTATE SALES LEAMINGTON st Ma Stratford Merio PDPOA PASS OFFICE, SECURITY, ADMIN LIGHTHOUSE t Lane u o Yard Fire Station b arm A ind p To Leamington Lane Up Side Fron g O Shore W t e n i d i Gate T w k S c Niblick a l S y S ack Hi t Port T L gh a Wa ST. ANDREWS o W rb w a o Fu wn ll S te a weep W r o COMMON r d Wind T D at ack Brassie Ct. e Queens Queens r Leamington Ct. -

Ocean Front Charming Beach House Next to the Dunes and Beach Entrance

Ocean Front Charming Beach House Next to the Dunes and Beach Entrance Summary This charming house was built around the 1930's. The best part about this property is that it is right on the beach. Description 3 bedrooms, upstairs sleeping loft, 1 full bath, 1 half bath, sleeps 14 This charming house was built around the 1930's. The best part about this property is that it is right on the beach. One can go to the beach, easily walk back for lunch or a snack, and return to the beach. There is an outside shower, a second floor deck, and a nice back yard for relaxing and grilling. More than one family can share this house and a wonderful feature is that the kids can all sleep upstairs in the loft and the parents can sleep downstairs in the 3 bedrooms on the first floor. The front porch is a great place to sit and read and watch the beach activity. People are walking to the beach with their surfboards and towels in tow and the ice cream truck makes many stops in front of the house. It is fun to see the children run for their ice creams. This property is next to the beach and in walking distance to surf shops, markets, and kids activities. Please contact owner for rental rates. Note: Until confirmed, rates are subject to change without notice. Other Amenities: We do not have a garden , but the whole house sits right by the beach and the dunes. There is a back yard with a grill, picnic table, and seating. -

Resort Phone Numbers Guest Information Events & Meetings Facilities 1 Welcome Center & Guest Check-In 11 Centre Court Pavilion 800–827–3006

Broad Creek Resort Phone Numbers Guest Information Events & Meetings Facilities 1 Welcome Center & Guest Check-in 11 Centre Court Pavilion 800–827–3006......... Reservations & Concierge Services 4 Guest Pass Office, Security & PDPOA Office 12 Dunes House Oceanfront Bar & Grill (golf, tennis, bikes, kayaking, camps, clinics, marina charters, fishing, dolphin tours, sport crabbing, water sports & more) Golf & Tennis Real Estate Sales & Rentals Marriott Harbour Point 5 Robert Trent Jones Golf Course, Pro Shop & Golf Academy 3 Dunes Real Estate & Sunset Pointe 843–785–9100.........Welcome Center & Check-In 56 6 Palmetto Dunes Tennis Center 14 George Fazio Golf Course, Pro Shop & Grille Arts, Recreation & Tourism 843–689–4222 ........ FREE Resort Transportation / Palmetto Dunes Buggy (seasonally) 15 Arthur Hills Golf Course, Pro Shop & Grille 25 The Arts Center of Coastal Carolina 237-64 Captain’s 63 Shelter Cove Executive Park Quarters 843–785–1120......... Palmetto Dunes Security Activities & Tours 64 Shelter Cove Community Park 57 55 SHIP’S STORE & MARINA OFFICE Resort Map 9 Hilton Head Outfitters & Bike Rentals 65 Hilton Head Island Chamber of Commerce The Anchorage 201-36 19 The Ship’s Store, Marina Office & Outside Hilton Head: fishing charters, boat rentals, 20 nature & dolphin cruises & water activities 19 Palmetto Dunes Buggy Other • Free shuttle bus service inside 2 Fire Station No. 6 54 Palmetto Dunes & Shelter Cove Harbour Shopping & Dining 23 Neptune Statue Yacht • 8:00 am – 9:00 pm daily 5 Big Jim’s BBQ, Burgers & Pizza Cove DISNEY’S -

Lake Charlevoix Cove Beach House Rules and Regulations 12/2018

Lake Charlevoix Cove Beach House Rules and Regulations 12/2018 All owners are free to use the Beach House and its amenities when enjoying the waterfront. Owners may also reserve the Beach House for larger functions such as reunions or holiday parties. Such functions, however, do not exclude individual owners from use of the Beach House, its amenities, or surrounding grounds during the function. Reservation Process - Such reservations are on a first come-first served basis and are made by contacting Board member Bill Morrison at [email protected] or (734)323-6335. Also, add your name to the calendar posted at the Beach House. There will be no reservations allowed for large groups on the 4th of July or its corresponding weekend. There will be a $75 fee for usage of the Beach House for a reserved function. Checks should be made payable to Lake Charlevoix Cove Association and may be given to Bill Morrison, or mailed to: Bill Morrison, P.O. Box 1329, East Jordan, MI. 49727. A deposit of $250 will be presented to Bill Morrison in the form of a check made out to Lake Charlevoix Cove Association. This check will be held until the function is over and the beach house inspected for damage. If no damage is found, the deposit check will be destroyed. The owner must sign a contract of use prior to the function. The contract will be available from Bill or on the LCCHOA web page. Rules for Use - An owner must be present during the entire function at the Beach House and will be responsible for the behavior of all guests including but not limited to compliance with all local and state regulations concerning alcoholic beverages. -

Plan Your Summer Party It’S As Easy As 1 - 2 - 3 2014 1

Plan Your Summer Party It’s as easy as 1 - 2 - 3 2014 1. Choose a Location Canopy on the Sand - Available during summer pool season • Reserve online up to 2 weeks in advance, beginning at 7am • $30 for a 3-hour reservation • Best for groups of up to 30 people • Reservation includes one 12’ x 12’ canopy + two 5’ tables • Reservations are available from 11am-2pm or 2:30pm-5:30pm. Three available per time slot; limit one per group. • Canopies are set up on the sand across from the courtyard entrance; canopies may not be moved. • Rent beach chairs from the Beach Rentals cart on the day of your party or bring your own towels, blankets or chairs. Courtyard or View Deck Tables & Chairs • Public space in the courtyard is available on a first come, first served basis during the summer season. • There is no charge for use of public space; your party is limited to using no more than 4 tables and 16 chairs for your group. Please note: Beach House umbrellas may not be moved. Personal chairs 1 and tables are not permitted in the courtyard or view deck. 2. Plan Party Activities There’s no fee for many summer site features and activities! Splash Pad • Beach Games • Playground • Rec Room Beach Volleyball, Tennis & Soccer • Play for free - first come, first served or reserve online 1-3 days prior; $10 for a one-hour reservation • Equipment available at Guest Services; no charge, subject to availability, ID required. Please note the following are prohibited: Smoking, dogs, alcohol, glass containers, fires/fireworks/bbqs/wick chafing fuel, large knives, balloons, securing bikes to railings, riding bikes/scooters/Segways in courtyards and walkways, personal canopies/umbrellas/tables/chairs in courtyards, moving Beach House umbrellas, amplified music, furniture deliveries from rental companies, attaching signage or decor to railings, walls or trees *Other restrictions may apply; guests must abide by the decision of Beach House staff regarding the interpretation of any rules.