66-6275 KIESLER, Sara Beth Greene, 1940— AN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2020 Virtual Commencement Exercises Click Here to View Ceremonies

SOUTHERN NEW HAMPSHIRE UNIVERSITY SPRING 2020 VIRTUAL COMMENCEMENT EXERCISES CLICK HERE TO VIEW CEREMONIES SATURDAY, MAY 8, 12 PM ET 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONFERRAL GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE DEGREES ........................................ 1 SNHU Honor Societies Honor Society Listing .................................................................................................. 3 Presentation of Degree Candidates COLLEGE FOR AMERICA .............................................................................................. 6 BUSINESS PROGRAMS ................................................................................................ 15 COUNSELING PROGRAMS ........................................................................................... 57 EDUCATION PROGRAMS ............................................................................................ 59 HEALTHCARE PROGRAMS .......................................................................................... 62 LIBERAL ARTS PROGRAMS .........................................................................................70 NURSING PROGRAMS .................................................................................................92 SOCIAL SCIENCE PROGRAMS ..................................................................................... 99 SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, ENGINEERING AND MATH (STEM) PROGRAMS ................... 119 Post-Ceremony WELCOME FROM THE ALUMNI ASSOCIATION ............................................................ 131 CONFERRAL OF GRADUATE -

2007 Annual Report

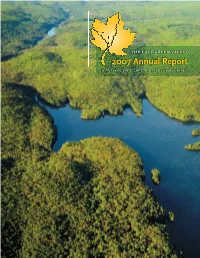

THE LAST GREEN VALLEY 2007 Annual Report QUINEBAUGSHETUCKET HERITAGE CORRIDOR, INC. W. REID MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRMAN OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS It is a privilege to report that 2007 has been a dramati- Th e goal is simple: preservation of our Last Green cally successful year for Quinebaug-Shetucket Heritage Valley. How have we done so? We have developed Corridor, Inc., as illustrated by the subsequent pages programs like the Green Valley Institute to assist local of this document. All of us who have been involved in land-use decision makers with continuing education in this enterprise recognize that this success is the result a system that is largely operated by volunteer com- of the tireless eff orts of residents, businesses, towns and missions and committees. Our grant programs have nonprofi ts to fulfi ll the mission of QSHC. disbursed more than $3 million to 300 projects to complete work identifi ed as important by local com- I suggest that at this time of annual refl ection we munities and nonprofi ts, gaining matching funds to remind ourselves about the signifi cance of the those dollars at the rate of 1:3, an extraordinary exam- Quinebaug and Shetucket Rivers Valley National ple of partnership. Th e 17th Annual Walking Week- Heritage Corridor and why it is essential that we bring endS, that raised awareness of our unique resources, forth renewed enthusiasm for its preservation. Th e and broke attendance records once again, continues to watershed of these beautiful river systems is the last be so popular that the program is expanding in 2008 predominately undeveloped region in the otherwise to include the entire month of October. -

Local Teacher Dies in Tragic I-75 Pile-Up OMS Band Director Brian Gallaher One of 6 Victims by TONY EUBANK Crash That Occurred Near the Ooltewah As a Trumpet Player

FRIDAY 161st yEar • no. 49 jUnE 26, 2015 ClEVEland, Tn 22 PaGES • 50¢ Local teacher dies in tragic I-75 pile-up OMS band director Brian Gallaher one of 6 victims By TONY EUBANK crash that occurred near the Ooltewah as a trumpet player. While at Lee, he was together two or three days a week.” Banner Staff Writer Exit 11 marker. He leaves behind a wife School of Music Scholarship recipient Fisher said Gallaher brought life and a and two children. and a winner of the Performance Award. great energy to their running group. An Ocoee Middle School band teacher Not only had Gallaher served as the The much-beloved OMS band director “He was our default conversationalist,” was among the six motorists killed middle school’s longtime band director, was remembered early this morning by Fisher said. Thursday evening in a massive Interstate he was named Building Level Teacher of longtime friend Cameron Fisher, coordi- More importantly, Fisher added 75 wreck that investigators believe the Year twice. He attended Westmore nator of Communications at the Church Gallaher was an extremely talented involved as many as nine vehicles and 15 Church of God, where he served as the of God International Offices. teacher and trumpet player. people. church’s student orchestra director. “I’ve known Brian for about 15 years,” Chattanooga Police Department Brian Gallaher, a Lee University grad- Gallaher earned his bachelor’s degree Fisher told the Cleveland Daily Banner. spokesman Kyle Miller said the I-75 acci- uate who had served as OMS band direc- from Lee University in 2000, and went on “Even though he was a bit younger than tor for 14 years, died in the 7:10 p.m. -

2016 Topps the Walking Dead Season 5 Trading Cards Checklist

BASE CARDS BASE CARDS 1 KILL ROOM 2 BOOM 3 "NOBODY'S GOTTA DIE TODAY" 4 ESCAPE FROM TERMINUS 5 REUNITED 6 NO SANCTUARY 7 "WE AIN'T DEAD" 8 GABRIEL CALLS FOR HELP 9 WET WALKERS 10 "I DON'T MISS THAT SWORD" 11 CELEBRATION DINNER 12 CHURCH ART 13 FINDING BOB 14 GABRIEL THE DAMNED 15 PROTECTIVE 16 NO POINT IN BEGGING 17 PROMISES KEPT 18 SAYING GOODBYE 19 WAKING UP 20 "WE'RE NOT TRAPPED" 21 RISING ABOVE 22 SEARCHING FOR THE KEY 23 GOING DOWN 24 NOAH ESCAPES 25 BUS CRASH 26 DON'T TRY TO FIND US 27 ELLEN 28 A VERY IMPORTANT MISSION 29 HOSED 30 LOOKING FOR BETH 31 INDOOR CAMPING 32 "YOU LOOK TOUGH" 33 FINDING THE CROSS 34 MUTUAL FRIEND 35 CAROL TAKES A HIT 36 BARRICADING THE CHURCH 37 BACK SOON 38 MAKING A PLAN 39 APPROACH WITH CAUTION 40 GABRIEL LISTENS INTENTLY 41 HOSTAGES 42 RETHINKING THE PLAN 43 MARY'S BIBLE 44 WALKERS TAKE OVER THE CHURCH 45 MAKING IT OUT 46 EXCHANGE 47 LOSS 48 GRIEF 49 OVERRUN 50 BITTEN 51 MAKING IT 52 PARTS 53 THE WAY IT HAD TO 54 GONE 55 A FUNERAL 56 KIDNAPPED WALKER 57 MAD DOGS 58 BATTLING EXHAUSTION 59 FEELING IT 60 PRAISE THE RAIN 61 "WE ARE THE WALKING DEAD" 62 ATTACK ON THE BARN 63 PEOPLE LIKE US 64 FINDING THE RV 65 ROADS NOT CLEARED 66 FLARE TO THE FACE 67 RED LIGHTS 68 THE GATES OF ALEXANDRIA 69 "WHO'S DEANNA?" 70 CURB APPEAL 71 A SHOWER AND A SHAVE 72 A NEW HOME 73 THE SUSPICIOUS HUSBAND 74 MISSING STASH 75 TARGET PRACTICE 76 TRY 77 HANGING IT UP 78 BUTTONS 79 JOB OFFER 80 ON PATROL 81 CRISIS OF FAITH 82 SIZING UP THE THREAT 83 ABRAHAM LEAVES NO ONE BEHIND 84 HOLD THE DOOR 85 EATEN ALIVE 86 A WARNING 87 A PROBLEM -

The Zen of Daryl: a New Masculinity Within AMC's the Walking Dead

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Honors Program Theses and Projects Undergraduate Honors Program 5-12-2015 The Zen of Daryl: A New Masculinity within AMC's The alW king Dead Sarah Jane Mulvey Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj Part of the Broadcast and Video Studies Commons, and the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons Recommended Citation Mulvey, Sarah Jane. (2015). The Zen of Daryl: A New Masculinity within AMC's The alW king Dead. In BSU Honors Program Theses and Projects. Item 104. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/honors_proj/104 Copyright © 2015 Sarah Jane Mulvey This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. The Zen of Daryl: A New Masculinity Within AMC’s The Walking Dead Sarah Jane Mulvey Submitted in Partial Completion of the Requirement of Departmental Honors in Communication Studies Bridgewater State University May 12, 2015 Dr. Jessica Birthisel, Thesis Director Dr. Jason Edwards, Committee Member Dr. Maria Hegbloom, Committee Member Mulvey 2 Chapter 1: Post-Apocalyptic Entertainment As New American Past-Time AMC’s The Walking Dead (TWD) is a pop culture phenomenon that reaches millions of viewers each week, ranging in age from 18 to 50 years old. Chronicling the trials and tribulations of a fictional group of survivors within a horror-fueled post-apocalyptic America, The Walking Dead follows in a long line of zombie- centered texts that reveal some of society’s deepest anxieties: the threat of overwhelming disease, the fall of societal infrastructure, and the breakdown of ideologies that we live our daily lives by. -

Download, Or Email Articles for Individual Use

University of Massachusetts Amherst From the SelectedWorks of Stephen Olbrys Gencarella April, 2016 Thunder without Rain: Fascist Maculinity in AMC's The alW king Dead Stephen Olbrys Gencarella Available at: https://works.bepress.com/stephen_gencarella/3/ HOST 7 (1) pp. 125–146 Intellect Limited 2016 Horror Studies Volume 7 Number 1 © 2016 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/host.7.1.125_1 STEPHEN OLBRYS GENCARELLA University of Massachusetts Thunder without rain: Fascist masculinity in AMC’s The Walking Dead ABSTRACT KEYWORDS In this article, I offer a critique of the five seasons of the television series The fascism Walking Dead (TWD) broadcast to date (2010–2015). As the popularity of this masculinity show continues to rise, many viewers have demonstrated a willingness to praise Male Fantasies TWD without carefully examining its narrative commitments to violence or to ghouls attack media critics who point out negative elements at work. My critique contends critique that the series is decidedly fascistic in nature, and celebratory of fascist masculin- The Walking Dead ity as the key to surviving an apocalyptic situation. I analyse the show through a comparison with the literature of the Freikorps as detailed by Klaus Theweleit’s study of fascism, Male Fantasies ([1977] 1987, [1978] 1989). I examine in detail the prevalence of the ‘soldier male’ in TWD, the limited roles for women, and the representation of the ghoulish undead, drawing upon Theweleit and related scholar- ship on fascist aesthetics. It is not the corpses that this man loves; he loves his own life. But he loves it … for its ability to survive. -

2016 Topps the Walking Dead Survival Box

2016 Topps The Walking Dead Survival Box BASE BASE CARDS 1 Rick Grimes 2 Carl Grimes 3 Daryl Dixon 4 Michonne 5 Glenn Rhee 6 Maggie Greene 7 Beth Greene 8 Hershel Greene 9 Shane Walsh 10 Dale Horvath 11 Merle Dixon 12 Andrea 13 Carol Peletier 14 Abraham Ford 15 The Governor 16 Tyreese Williams 17 Sasha Williams 18 Bob Stookey 19 Paul "Jesus" Rovia 20 Tara Chambler 21 Eugene Porter 22 Rosita Espinosa 23 Gabriel Stokes 24 Noah 25 Enid 26 Jessie Anderson 27 Pete Anderson 28 Sam Anderson 29 Lizzie Samuels 30 Mika Samuels 31 Nicholas 32 Dawn Lerner 33 Tobin 34 Reg Monroe 35 Alpha Wolf 36 Denise Cloyd 37 Otis 38 Caesar Martinez 39 Milton Mamet 40 Karen 41 Shumpert 42 Axel 43 Jimmy 44 Tomas 45 Caleb Subramanian 46 Joe 47 Rick & Carl Grimes 48 Daryl & Merle Dixon 49 Glenn Rhee & Maggie Greene 50 Tyreese & Sasha Williams INSERT BASE CARD SHORT PRINTS 1 Rick Grimes 2 Carl Grimes 3 Daryl Dixon 4 Michonne 5 Glenn Rhee 6 Maggie Greene 7 Beth Greene 8 Hershel Greene 9 Shane Walsh 10 Dale Horvath 11 Merle Dixon 12 Andrea 13 Carol Peletier 14 Abraham Ford 15 The Governor 16 Tyreese Williams 17 Sasha Williams 18 Bob Stookey 19 Paul "Jesus" Rovia 20 Tara Chambler 21 Eugene Porter 22 Rosita Espinosa 23 Gabriel Stokes 24 Noah 25 Enid WALKER BITE CARDS 1 Dale Horvath 2 Andrea 3 Tyreese Williams 4 Bob Stookey 5 Noah KILL OR BE KILLED 1 Shane Walsh vs. Otis 2 Rick Grimes vs. Shane Walsh 3 Carol vs. -

THE MOSTLY TRUE ADVENTURES of a HOOSIER SCHOOLMASTER: a Memoir

THE MOSTLY TRUE ADVENTURES OF A HOOSIER SCHOOLMASTER: A Memoir Ralph D. Gray 0 The Mostly True Adventures of A Hoosier Schoolmaster: A Memoir Ralph D. Gray Bloomington, Indiana 2011 1 Contents Chapter Page Preface 3 1. The Grays Come to Pike County 5 2. An Otwell Kid 20 3. The Three R’s 29 4. The War Years in Otwell and Evansville 42 5. Living in Gray’s Grocery 52 6. Hanover Daze 70 7. Going Abroad 91 8. How to Make Gunpowder 111 9. “Hail to the Orange, Hail to the Blue” 129 10. On Being a Buckeye 141 11. “Back Home Again in Indiana” 153 12. To the Capital City 172 13. On Becoming an Indiana Historian 182 14. The Editorial We (and Eye) 205 15. Travels, Travails, and Transitions 219 16. A New Life 238 Appendices 250 A. Additional family photographs 250 B. List of illustrations 256 C. List of book publications 259 2 This book is dedicated, with love and appreciation, to the KiDS Karen, David, and Sarah 3 Preface ccording to several people, mainly those, I suppose, who have already written their memoirs, everybody should write about their own lives, primarily for A family members, but also for themselves and others. I started drafting these pages in 2009, thinking I would have a complete manuscript in a matter of months and perhaps a published book in 2010. Now it appears, having completed the first draft in the latter part of 2010, that a version of this work accessible probably on line to others might be available sometime in 2011 or a bit later. -

Jackson Self Mary Beth Greene Arlene Parnofiello Principal Principal in Training Dean of Students Renaissance Charter School At

6696 S. Military Trail Lake Worth, Florida 33463 Ph. 561-209-7106 Fax 561-209-7107 www.centralpalmcharter.org Member of Charter Schools USA Governed by Renaissance Charter School, Inc. Renaissance Charter School at Central Palm Family Involvement Policy/Plan School Year 2016-2017 Summary Renaissance Charter School at Central Palm recognizes the importance of forming a strong partnership with parents and community members in order to positively impact the students in our school. To promote effective parent involvement, the staff at Central Palm welcomes input from parents and community members in decision making and encourages them to join us in the activities outlined in this plan. We work with parents as equal partners in the educational process. Annual Meeting Parents are invited to attend this meeting at the beginning of each school year to learn more about the requirements of Title I and our School-wide Title I Program. At this meeting there will be opportunities to review the Title I documents and give input into the following: • School Parent- Compact • Title I Family Involvement Policy/Plan • Parents’ Right to Know • Ideas of topics for future parent involvement activities • Title I budget Accessibility for all families We will accommodate all families by providing the following: • Choices of meeting dates and times based on input from parents • Interpreters • Translated documents • Childcare at the school Parent Involvement Activities Based on parent survey input, we will provide the following activities to assist parents in understanding the state curriculum and assessments and to help parents improve their children’s academic achievement: Ø Family Literacy Nights will be implemented for parents so parents can learn strategies to help children at home; so that children can increase reading achievement. -

Networkmagazine-Summer2010.Pdf

Letter from the Dean Dear alumni and friends, For many decades, College of Education faculty, students, staff and alumni have been ac- tively involved in improving education in Kentucky and around the world – but never before like now. In February 2010, the College launched a bold new initiative, the Kentucky P20 Inno- vation Lab (http://p20lab.org/), designed to transform, not just incrementally change, our current education system from preschool through graduate education with a focus on per- sonalized learning and world-class knowledge and skills. To ensure that every child – from early childhood through adolescence into adulthood – is well-prepared for life, meaningful work and citizenship, we know that all parts of the educational system must work together. UK President Lee T. Todd, Jr. believes “the P20 Lab will help ensure that our campus break- throughs hit the ground in Kentucky and change lives in every community. It will provide a unique vehicle to deliver cutting-edge discoveries from UK’s 17 colleges into schools and communities across the Commonwealth.” In this issue, we are delighted to showcase individuals and groups who help us bring inno- vation and breakthroughs into our collective educational future, such as COST: Consortium for Overseas Student Teaching; nationally-approved programs such as school psychology; new college and department leaders; award-winning students, faculty and alumni; and the first Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) Education symposium sup- ported jointly by the colleges of Education, Arts & Sciences and Engineering. You will discover how our efforts are attracting outstanding new educators and clinical profes- sionals when you visit the College’s new website: http://education.uky.edu/. -

9L0

</. b "(y ')3 -\ 9l0 < -27, ' ' Features__ _ 1986 Sigma Kappa National Convention ........................... 2 Vol. 80 Summer No.1 1985 Official magazine of Sigma Kappa Soror· ity founded at Colby College, Waterville, Maine, November 9, 1874. NATIONAL COUNCIL National President: Phyllis Harris Mark· ley (Mrs. Donald), 1802 West Moss, The excellence of Sigma Kappa college women from Peoria, IL 61606 National Vice President for Alumnae: coast to coast is impressive. Join in celebration of Margaret Miller Dodd (Mrs. William), Our Very Best ............................. ..... 4-9 1955 Windsor Road, Bethlehem, P A 18017 National Vice President for Collegiate Chapters: Carol Jackson Phillips (Mrs. Richard), P.O. Box 467, Moreno, CA 92360 National Vice President for Expansion: Linda Oden Berkshire (Mrs. Rice), A cuddly critter often is good company for the lonely 31910 Avenida Evita, San Juan Capistrano, CA 92675 elderly or hospitalized convalescent. Trenton/Delta National Secretary: Ms. Sheila A. ware Valley Sigmas report on Barnes, 1608 Pepperidge Road, Soft whiskers ........ ............................ 13 Asheboro, NC 27203 National Treasurer: Marylou Sayler Fiesta at Palm Springs ................ .. ..... .. ................. 15 Turner (Mrs. John), 645 W. 69th St., Loyalty Fund: Looking back ... to the future ..................... 31 Kansas City, MO 64113 National Panhellenic Conference Dele gate: Ruth Rysdon Miller (Mrs. Karl B.), 13020 S. W. 92nd Ave., A312, Mi ami, FL 33176 CENTRAL OFFICE Director of Central Office: Lois Waltz Vernon (Mrs. Robert), 1717 West 86th Departments__ Street, Suite 600, Indianapolis, IN 46260 317-872-3275 Financial Administrator: Theresia Walk er Hoggatt (Mrs. Jerome) TRIANGLE STAFF Editor: Linda Wright Bardach (Mrs. From the Alumnae .. ........... .... .... .. ....... .... ......... 10-17 Neil), c/o Anacomp, P.O. -

Kansas Maternal and Child Health Council (KMCHC) Meeting

Kansas Maternal and Child Health Council (KMCHC) Meeting Wednesday, July 25, 2018 Member Attendees Absent Visitors Rebecca Adamson, APRN-C Lawrence Panas Stefanie Baines, CES Danielle Brower Carrie Akin Susan Pence, MD Linda Blasi Whitney Downing Brenda Bandy, IBCLC Cari Schmidt, PhD Ellie Brent, MPH Ashley Hervey Kourtney Bettinger, MD, MPH Katie Schoenhoff Joseph Caldwell Jessica Looze Kayzy Bigler Christy Schunn, LSCSW Greg Crawford Tammy Broadbent Pam Shaw, MD, FAAP Denise Cyzman Lisa Chaney Sookyung Shin Mary Delgado, APRN Stephanie Coleman Rachel Sisson, MS Stephen Fawcett, PhD Julia Connellis Heather Smith, MPH Lisa Gabel, RN, BSN Dennis Cooley, MD, FAAP Kasey Sorell, BSN, RN Lori Haskett Sarah Fischer, MPA Lori Steelman Charles Hunt, MPH Beth Fisher, MSN, RN Jenny Taylor Kimberly Kasitz Terrie Garrison, RN, BSN Lisa Williams Patricia Kinnaird Deanna Gaumer Stephanie Wolf, RN, BSN Steve Lauer, MD, PhD Cory Gibson, EdD Donna Yadrich Annie McKay Beth Greene Patricia McNamar, DNP, ARNP, NP-C Kari Harris, MD Brian Pate, MD, FAAP Sara Hortenstine Melody McCray-Miller Elaine Johannes, PhD Mohamed Radhi, MD Tamara Jones, MPH Cherie Sage Peggy Kelly Sharla Smith, PhD, MPH Jamie Kim, MPH Chris Steege Kelli Mark David Thomason, MPA Elisa Nehrbass, Med Na’shell Williams Staff Mel Hudelson Connie Satzler Agenda Items Discussion Action Items Welcome & Recognize Members were welcomed, new KMCHC members were introduced New Members/Guest Review & Approval of It was moved to approve the minutes from April 18, 2018, all approved. April 18, 2018 Minutes Jennifer Montgovery from the Attorney General’s office gave a Exploitation & Human presentation on human trafficking in Kansas.