EDITORIAL 27 July 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Secretariat Phones

H.P.SECRETARIAT TELEPHONE NUMBERS th AS ON 09 August, 2021 DESIGNATION NAME ROOM PHONE PBX PHONE NO OFFICE RESIDENCE HP Sectt Control Room No. E304-A 2622204 459,502 HP Sectt Fax No. 2621154 HP Sectt EPABX No. 2621804 HP Sectt DID Code 2880 COUNCIL OF MINISTERS CHIEF MINISTER Jai Ram Thakur 1st Floor 2625400 600 Ellerslie 2625819 Building 2620979 2627803 2627808 2628381 2627809 FAX 2625011 Oak-Over 858 2621384 2627529 FAX 2625255 While in Delhi Residence Office New Delhi Tel fax 23329678 Himachal Sadan 24105073 24101994 Himachal Bhawan 23321375 Advisor to CM + Dr.R.N.Batta 1 st Floor 2625400 646 2627219 Pr.PS.to CM Ellersile 2625819 94180-83222 PS to Pr.PS to CM Raman Kumar Sharma 2625400 646 2835180 94180-23124 OSD to Chief Minister Mahender Kumar Dharmani E121 2621007 610,643 2628319 94180-28319 PS to OSD Rajinder Verma E120 2621007 710 94593-93774 OSD to Chief Minister Shishu Dharma E16G 2621907 657 2628100 94184-01500 PS to OSD Balak Ram E15G 2621907 757 2830786 78319-80020 Pr. PS to Diwan Negi E102 2627803 799 2812250 Chief Minister 94180-20964 Sr.PS to Chief Minister Subhash Chauhan E101 2625819 785 2835863 98160-35863 Sr.PS to Chief Minister Satinder Kumar E101 2625819 743 2670136 94180-80136 PS to Chief Minister Kaur Singh Thakur E102 2627803 700 2628562 94182-32562 PS to Chief Minister Tulsi Ram Sharma E101 2625400 746,869 2624050 94184-60050 Press Secretary Dr.Rajesh Sharma E104 2620018 699 94180-09893 to C M Addl.SP. Brijesh Sood E105 2627811 859 94180-39449 (CM Security) CEO Rajeev Sharma 23 G & 24 G 538,597 94184-50005 MyGov. -

CL 143-27 Meeting GST Council Members

ALL INDIA BANK EMPLOYEES' ASSOCIATION Central Office: “PRABHAT NIVAS” Regn. No.2037 Singapore Plaza, 164, Linghi Chetty Street, Chennai-600001 Phone: 2535 1522 Fax: 2535 8853 Web: www.aibea.in e mail ~ [email protected] & [email protected] M 98400 89920 CIRCULAR LETTER No. 28/143/2019/27 10-10-2019 TO ALL OFFICE BEARERS, STATE FEDERATIONS AND ALL INDIA BANKWISE ORGANISATIONS Dear Comrades, Reg: Exemption of GST on premium payable on Group Medical Insurance Policy for the retired employees/officers. Units are aware that AIEBA has taken up the matter with the Finance Minister and the GST Council for exempting Mediclaim policy premium paid by the retirees from the purview of GST. The matter has been taken up with IBA who have also represented to the Government not to levy GST on the premium. Since the exemption can be given only by the GST Council, we had asked all our State Federations to contact the respective GST Council Members from their States to follow up the matter and to take up the issue in the next meeting of the GST Council. Today, in Chennai, we met Shri D. Jayakumar, Hon. Minister for Personnel & Administrative Reforms, Govt. of Tamilnadu who is the Member of GST Council representing Tamilnadu Government. We submitted a copy of our letter to Finance Minister and explained the issue in detail. He was appreciative of the reasonableness of our demand and assured to write to the GST Council to discuss the issue. He also assured to pursue the matter in the GST Council meeting. He suggested that we should meet other members of the GST Council in this regard so that the issue gets some momentum. -

India State Chief Ministers

Chief Ministers of India Took office S.No State/UT Name (tenure length) Party Cabinet 1 Andhra Pradesh Y. S. Jaganmohan Reddy 5/30/2019 (1 year, 184 days) YSR Congress Party Jagan I 2 Arunachal Pradesh Pema Khandu 7/17/2016 (4 years, 136 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Khandu II 3 Assam Assam 5/24/2016 (4 years, 190 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Sonowal I 4 Bihar Nitish Kumar 2/22/2015 (5 years, 282 days) Janata Dal (United) Nitish VII 5 Chhattisgarh Bhupesh Baghel 12/17/2018 (1 year, 349 days) Indian National Congress Baghel I 6 Delhi Arvind Kejriwal 2/14/2015 (5 years, 290 days) Aam Aadmi Party Kejriwal III 7 Goa Pramod Sawant 3/19/2019 (1 year, 256 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Sawant I 8 Gujarat Vijay Rupani 7 August 2016 (4 years, 115 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Rupani II 9 Haryana Manohar Lal Khattar 10/26/2014, (6 years, 35 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Khattar II 10 Himachal Pradesh Jai Ram Thakur 12/27/2017, (2 years, 339 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Jai Ram Thakur I 11 Jammu and Kashmir N/A (President's rule) 10/31/2019 (1 year, 30 days) N/A N/A 12 Jharkhand Hemant Soren 12/29/2019 (337 days) Jharkhand Mukti Morcha Soren II 13 Karnataka B. S. Yediyurappa 7/26/2019 (1 year, 127 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Yediyurappa IV 14 Kerala Pinarayi Vijayan 5/25/2016 (4 years, 189 days Communist Party of India (Marxist) Pinarayi I 15 Madhya Pradesh Shivraj Singh Chouhan 3/23/2020 (252 days) Bharatiya Janata Party Shivraj IV 16 Maharashtra Uddhav Thackeray 11/28/2019 (1 year, 2 days) Shiv Sena Thackeray I 17 Manipur N. -

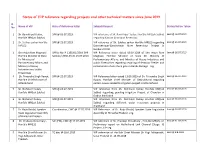

Status of VIP Reference Regarding Projects and Other Technical Matters Since June 2019

Status of VIP reference regarding projects and other technical matters since June 2019 Sl. No Name of VIP Date of Reference letter Subject/Request Status/Action Taken No 1 Sh. Ram Kripal Yadav, SPR @ 03.07.2019 VIP reference of Sh. Ram Kripal Yadav, Hon'ble MP(Lok Sabha) Sent @ 16.07.2019 Hon'ble MP(Lok Sabha) regarding Kadvan (Indrapuri Reservior) 2 Sh. Subhas sarkar Hon'ble SPR @ 23.07.2019 VIP reference of Sh. Subhas sarkar Hon'ble MP(LS) regarding Sent @ 25.07.2019 MP(LS) Dwrakeshwar-Gandheswar River Reserviour Project in Bankura (W.B) 3 Shri Arjun Ram Meghwal SPR Lr.No. P-11019/1/2019-SPR VIP Reference letter dated 09.07.2019 of Shri Arjun Ram Sent @ 26.07.2019 Hon’ble Minister of State Section/ 2900-03 dt. 25.07.2019 Meghwal Hon’ble Minister of State for Ministry of for Ministry of Parliamentary Affairs; and Ministry of Heavy Industries and Parliamentary Affairs; and public Enterprises regarding repairing of ferozpur Feeder and Ministry of Heavy construction of one more gate in Harike Barrage -reg Industries and public Enterprises 4 Sh. Trivendra Singh Rawat, SPR @ 22.07.2019 VIP Reference letter dated 13.06.2019 of Sh. Trivendra Singh Sent @ 26.07.2019 Hon’ble Chief Minister of Rawat, Hon’ble Chief Minister of Uttarakhand regarding Uttarakhand certain issues related to irrigation project in Uttarakhand. 5 Sh. Nishikant Dubey SPR @ 03.07.2019 VIP reference from Sh. Nishikant Dubey Hon'ble MP(Lok Sent @ 26.07.2019 Hon'ble MP(Lok Sabha) Sabha) regarding pending Irrigation Project of Chandan in Godda Jharkhand 6 Sh. -

10.05.2021 News in Short Daily Current Affairs

09.05.2021 – 10.05.2021 This CURRENT AFFAIRS bulletin is prepared to help students learn DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS within 10 MINUTES Join in our Daily Current Affairs (DCA) TELEGRAM Channel http://t.me/racedca - For Current Affairs & all the important updates regarding Bank, SSC & Railways Exams. NEWS IN SHORT ① : Himachal Pradesh CM launches ⑥ : Sunder Pichai, Punit Renjen and Shantanu ‘Mukhyamantri Sewa Sankalp Helpline 1100’ Narayen join the global Covid task force ② : Himanta Biswa Sarma sworn-in as 15th Chief ⑦ : Anupam Kher bags best actor award at new Minister of Assam york city international film festival ③ : Madya Pradesh launches new scheme ⑧ : Kalki Koechlin authors her debut book on “Mukhya Mantri Covid Upchar Yojana” motherhood “Elephant In The Womb” ④ : SBI and EIB to invest up to Euro 100 million in ⑨ : Renowned sculptor and Rajya Sabha MP Indian SMEs Raghunath Mohapatra passed away ⑤ : Prime Minister Narendra Modi participates in ⑩ : Lewis Hamilton wins 2021 Spanish Grand Prix India-EU Leaders Summit 2021 DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS – 09.05.2021 – 10.05.2021 NATIONAL & INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS • Under this scheme, important decisions have also been taken for free Covid treatment of families Himachal Pradesh CM Jai Ram Thakur launches dedicated possessing Ayushman cards. COVID-19 ‘Mukhyamantri Sewa Sankalp Helpline 1100’ SBI and EIB to invest up to Euro 100 million in Indian SMEs • Chief Minister of Himachal Pradesh, Jai Ram Thakur focused on climate change and sustainability launched dedicated COVID-19 Helpline ‘Mukhyamantri • The European Investment Bank (EIB) and State Bank Sewa Sankalp Helpline 1100’ for facilitating the people of India (SBI) entered into a pact to jointly raise Euro regarding COVID related issues in Shimla. -

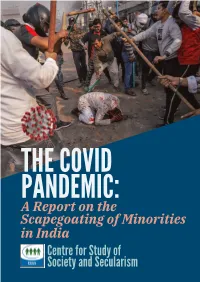

THE COVID PANDEMIC: a Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism I

THE COVID PANDEMIC: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism i The Covid Pandemic: A Report on the Scapegoating of Minorities in India Centre for Study of Society and Secularism Mumbai ii Published and circulated as a digital copy in April 2021 © Centre for Study of Society and Secularism All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including, printing, photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher and without prominently acknowledging the publisher. Centre for Study of Society and Secularism, 603, New Silver Star, Prabhat Colony Road, Santacruz (East), Mumbai, India Tel: +91 9987853173 Email: [email protected] Website: www.csss-isla.com Cover Photo Credits: Danish Siddiqui/Reuters iii Preface Covid -19 pandemic shook the entire world, particularly from the last week of March 2020. The pandemic nearly brought the world to a standstill. Those of us who lived during the pandemic witnessed unknown times. The fear of getting infected of a very contagious disease that could even cause death was writ large on people’s faces. People were confined to their homes. They stepped out only when absolutely necessary, e.g. to buy provisions or to access medical services; or if they were serving in essential services like hospitals, security and police, etc. Economic activities were down to minimum. Means of public transportation were halted, all educational institutions, industries and work establishments were closed. -

Page10 Local.Qxd (Page 1)

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 23, 2018 (PAGE 10) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU Sumitra Mahajan bats for ‘one Moon mission a calculated risk: ISRO chairman Bangladeshi migrants like ‘termites’, HYDERABAD, Sept 22: ninth Convocation of GITAM Gbps high bandwidth connectiv- nation, one election’ formula Deemed to be University at ity,which will help bridge the ISRO's moon mission SHIMLA, Sept 22: cial for the nation if Lok Sabha Rudraram in neighbouring digital divide", he said. Chandrayaan 2, a 'calculated Sangareddy district. Sivan said the Centre has will be sent out of country: Shah and Assembly elections were risk' undertaken in the knowl- Lok Sabha speaker Sumitra Sivan said India will have its approved Rs 10,900 crore for 30 JAIPUR, Sept 22: list. The Congress cannot do any held simultaneously. edge that 50 per cent of such Mahajan on today backed the first demonstration flight of PSLVs and 10 GSLV Mk-III At another meeting in Kota, good for the country as that The formula of one nation, launches have failed, will land at concept of holding simultaneous SSLV by mid-2019, which launches in the next four years, BJP president Amit Shah he said the Congress treated party has neither a leader nor a one election should be followed, a spot where no country has Parliamentary and Assembly would be the cheapest launch in addition to more than 50 said today Bangladeshi "infiltrators" as a vote bank policy, he said. she said. gone before,its chairman K migrants are like "termites" and polls stressing that it would be vehicle in the world with the spacecraft. -

List of Cm , Governors & Capitals

LIST OF CM , GOVERNORS & CAPITALS UPDATED TILL SEPTEMBER 2018 STATIC GK Free Static GK Material - Bankersdaily www.bankersdaily.in | www.bankersdaily.testpress.in | www.raceinstitute.in LIST OF CM , GOVERNORS & CAPITALS UPDATED TILL SEPTEMBER 2018 STATES S. NO States Chief Minister Governor Capitals Shri. Nara Chandrababu 1 Andhra Pradesh Naidu Shri E.S Lakshmi Narasimhan Amaravati 2 Arunachal Pradesh Shri Pema Khandu Brigadier BD Mishra (Retd) Itanagar, Guwahati 3 Assam Shri Sarbananda Sonowal Jagdish Mukhi Dispur 4 Bihar Shri Nitish Kumar Lalji Tandon Patna 5 Chhattisgarh Dr. Raman Singh Shri Anandiben Patel Raipur 6 Goa Shri Manohar Parrikar Smt. Mridula Sinha Panaji 7 Gujarat Shri Vijaybhai R. Rupani Shri Om Prakash Kohli Gandhinagar 8 Haryana Shri Manohar Lal Shri Satyadeo Narain Arya Chandigarh 9 Himachal Pradesh Shri Jai Ram Thakur Shri Acharya Dev Vrat Shimla Srinagar (Summer) 10 Jammu and Kashmir Governor’s rule Shri Satya Pal Malik Jammu (Winter) 11 Jharkhand Shri Raghubar Das Shrimati Droupadi Murmu Ranchi 12 Karnataka Sh. H.D. Kumaraswamy Shri Vajubhai Vala Bangalore Shri Justice (Retd.) Palaniswamy 13 Kerala Shri Pinarayi Vijayan Sathasivam Thiruvananthapuram 14 Madhya Pradesh Shri Shivraj Singh Chouhan Anandiben Patel Bhopal 15 Maharashtra Shri Devendra Fadnavis Shri Chennamaneni Vidyasagar Rao Mumbai 16 Manipur Nongthombam Biren Singh Dr. Najma A. Heptulla Imphal 17 Meghalaya Conrad Sangma Tathagata Roy Shillong 18 Mizoram Shri Lal Thanhawla Shri Kummanam Rajasekharan Aizawl 19 Nagaland Shri. Neiphiu Rio Shri Padmanabha Balakrishna Acharya Kohima 20 Odisha Shri Naveen Patnaik Prof. Ganeshi Lal Bhubaneswar Shri Captain Amarinder 21 Punjab Singh Shri V.P. Singh Badnore Chandigarh 22 Rajasthan Smt. -

Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel

Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel WWW.AMBITIOUSBABA.COM Page 1 Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel 1st October Q1. PM Narendra Modi has addressed the program 'Satyagraha se Swachhagraha' in Champaran. Champaran is located in which state? (a) Jharkhand (b) West Bengal (c) Odisha (d) Bihar (e) Uttar Pradesh Q2. Vodafone will merge with which company to make the largest mobile operator in India? (a) MTNL (b) Reliance Jio (c) BSNL (d) Airtel (e) Idea Cellular Q3. In which city of Rajasthan turned into yoga city when nearly 2 lakh people performed yoga on Yoga Day 2018 together to break Mysore's 2017 record of most people performing yoga at one place at the same time? (a) Bhilwara (b) Jodhpur (c) Kota (d) Jaipur (e) Bikaner Q4. Which Bank's credit card issuer has announced the launch of 'ELA' (Electronic Live Assistant), a virtual assistant for customer support and services? (a) State Bank of India (b) HDFC Bank (c) Bank of Baroda (d) Axis Bank (e) Punjab National Bank Q5. Which Bank is all set to roll out a capacity building project with farmers in Haryana and Rajasthan under its ‘Livelihood and Water Security’ CSR initiative? (a) ICICI Bank (b) Bank of India (c) State Bank of India (d) Kotak Mahindra Bank (e) Yes Bank WWW.AMBITIOUSBABA.COM Page 2 Facebook Page Facebook Group Telegram Group Telegram Channel Q6. Who was conferred the ‘Chief Minister of the Year’ award for her remarkable work in egovernance the award was given at the 52nd Skoch Summit held in New Delhi? (a) Vasundhara Raje Scindia (b) Jai Ram Thakur (c) Shivraj Singh Chouhan (d) Raman Singh (e) Devendra Fadnavis Q7. -

Chief Minister Jai Ram Thakur Said That the State Government Has

4/20/2020 about:blank 13th April 2020 For Press Chief Minister Jai Ram Thakur said that the State Government has taken several preventive measures to check spread of COVID-19 pandemic in the State besides ensuring that people are provided essential commodities at their door steps or atleast nearer to their homes. Chief Minister was addressing the Ministers, MPs, BJP MLAs and BJP candidates who were in fray in Vidhan Sabha elections through video conferencing from Shimla today. He said that the State Government imposed curfew throughout the State from 24th March, 2020 to avoid overcrowding and maintaining the norms of social distancing. He said that till date 1113 persons have been investigated for COVID-19 and 32 were tested positive. Out of these 32 persons, as many as 12 patients have been cured, four have migrated out of the State and one person had died adding that at present there were 15 active cases within the State. Jai Ram Thakur said that above cases have been reported from five districts of the State which include 14 cases from Una district, nine from Solan district, four each from Chamba and Kangra districts and one from Sirmaur district. Chief Minister said that the State Government has made adequate arrangements for providing plant protection material for the horticulturists and farmers. He said that representatives of PRIs and Urban Local Bodies have been involved to provide essential commodities to the people nearer to their homes. Jai Ram Thakur said that effective steps were also taken by the State Government to trace out travel history of Tablighi Jamaatis and their contacts to mitigate the impact of corona virus. -

11Th December Current Affairs

11th December Current Affairs 5 Sports Event Venue 2022 FIFA Men's World Cup Qatar 2026 FIFA Men's World Cup Canada, Mexico, United States 2023 FIFA Women's World Cup Australia, New Zealand 2023 FIFA U-20 Men's World Cup Indonesia 2022 FIFA U-20 Women’s World Cup Costa Rica 2023 FIFA U-17 Men's World Cup Peru 2022 FIFA U-17 Women's World Cup India 2020 FIFA Club World Cup (2021)_7 Team Qatar 4 5 2 3 Pulitzer Prizes Darnella Frazier/ डार्नेला फ्रे जयर Special Awards and Citations , For courageously recording the murder of George Floyd The New York Times Public Service, For courageous coverage of the coronavirus pandemic Louise Erdrich/ लुईस एरजिच Fiction, (Novel) The Night Watchman, by Louise Erdrich (Harper) Natalie Diaz/ र्नताली जडया Poetry, Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalie Diaz (Graywolf Press) Tania Leon/ ताजर्नया जलयोर्न Music, Stride, by Tania Leon (Peermusic Classical) Katori Hall/ कटोरी हॉल Drama, The Hot Wing King, by Katori Hall Megha Rajagopalan/ मेघा राजगोपालर्न International Reporting, BuzzFeed News ग International Reporting, BuzzFeed NewsﴂAlison Killing/ एजलसर्न जकजल Christo Buschek/ जिटो बशु चेक International Reporting, BuzzFeed News 1 2 5 5 1 5 1 2 5 3 1 Haryana Chandigarh (AG) Manohar Lal Khattar Bandaru Dattatreya Himachal Pradesh Summer: Shimla + Winter: Dharamshala Jai Ram Thakur Rajendra Arlekar Jharkhand Ranchi Hemant Soren Ramesh Bais Karnataka Bengaluru B. S. Yediyurappa Thawar Chand Gehlot Madhya Pradesh Bhopal (AG) Shivraj Singh Chouhan Mangubhai C. Patel Madagascar Antananarivo Ariary Malawi Lilongwe Kwacha Malaysia Kuala Lumpur Ringgit Maldives Male Rufiyaa Mali Bamako Franc : 1 4 2 Waman S Prabhu Manohar Parrikar- Off the Record S Y Quraishi The Population Myth: Islam, Family Planning and Politics in India A K Singh + Narender Kumar Battle Ready for 21st Century 1 Konsam Himalaya Singh Making of a General-A Himalayan Echo R Giridharan Right Under our Nose R Kaushik India’s 71-Year Test: The Journey to Triumph in Australia Ramesh Kandula Maveric Messiah: A political biography on AP Cm N T Rama Rao 2 4 1 5 5 2 . -

Media Should Give Greater Coverage to Development by : INVC Team Published on : 18 Apr, 2018 05:00 PM IST

Media should give greater coverage to development By : INVC Team Published On : 18 Apr, 2018 05:00 PM IST INVC NEWS Shimla, Press was the fourth pillar of democracy and for a strong and vibrant democracy it was imperative to have a free and fearless press. The Chief Minister Jai Ram Thakur stated this while addressing the gathering at Chandigarh today on the occasion of 18th Anniversary celebrations of Hindustan Times. Shri Jai Ram Thakur said that the Hindustan Times during 18 years of existence of its Chandigarh edition had created a special place in the hearts of the readers in the region. He said that the paper due to its fearless and fair reporting has emerged as a role model of professionalism. The Chief Minister said that the media should give greater coverage to development reporting particularly the rural issues. He said that the Hindustan Times has provided a platform for the three neighbouring states to ponder over the issues of mutual interest. The Chief Minister said that the Hindustan times was established in 1924 and during all these years it has emerged at the epitome of fair and free journalism. He said that the Chandigarh edition has reached adulthood and with this the responsibilities have also increased manifold. He said that to survive in the present era of cut throat competition the Hindustan Times has not only survived but has pioneered in many fields. Shri Jai Ram Thakur also announces Rs. 5 lakh for Press Club Chandigarh. Editor Hindustan Times Shri Ramesh Vinayak presented vote of thanks. Governor Punjab Shri VP Singh Badnor, Chief Minister Haryana Shri Manohar Lal Khattar, Chief Minister Punjab Capt.