Every Drop Is Precious: Greywater As an Alternative Water Source

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reuse: a Safe and Effective Way to Save Water

SOUTH FLORIDA WATER MANAGEMENT DISTRICT Water Reuse: A safe and effective way to save water ON THE INSIDE The demand for water is projected to increase over the long term in n Reclaimed water and reuse explained South Florida. Urban populations, agricultural operations and the environment depend on adequate water supplies. Fresh ground n Reuse success stories water and surface water will not be sufficient to satisfy all future n Reuse on a regional level demands. Meeting this growing thirst hinges on efforts to develop How water is reclaimed n alternative water sources. This brochure looks at one of the ways to n Purple pipes signify conserve Florida’s water resources — reclaiming water for reuse. reclaimed water Consider what happens to the water used inside the home. Once down the drain, this water is piped to the local wastewater treatment plant where it undergoes treatment to meet state standards for disposal. Historically, most of the water was disposed by injecting it deep underground or by discharging to surrounding waters or to the ocean. This is a wasteful way to treat such a valuable resource. More and more communities are finding that wastewater need not be wasted. They are reclaiming this water for irrigation of residential lots, golf courses, sports fields and orange groves; industrial cooling; car washing; fire protection; and Reclaimed water sign in Collier County groundwater recharge. Reuse is also beneficial to the environment. Success Stories During times of drought, reclaimed water •Pompano Beach – The city takes is a dependable source of water because wastewater being piped to the ocean, its availability is not dependent on rainfall. -

The Role of Water Reclamation in Water Resources Management in the 21St Century

THE ROLE OF WATER RECLAMATION IN WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT IN THE 21ST CENTURY K. Esposito1*, R. Tsuchihashi2, J. Anderson1, J. Selstrom3 1*: Metcalf & Eddy, 60 East 42nd Street, 43rd Floor, New York, NY 10165 2: Metcalf & Eddy, 719 2nd Street, Suite 11, Davis, CA 95616 3: Metcalf & Eddy, 2751 Prosperity Ave Suite 200, Fairfax, VA 22031 ABSTRACT In recognition of the existing and impending stress to traditional water supply, water planners must look beyond structural developments and interbasin water transfers to secure supply into the future. In this process, it is becoming evident that various issues related to water must be integrated into a whole system approach, including water supply, water use, wastewater treatment, stormwater management, and management of surrounding water environment. In bringing disparate water assets together, alternatives to traditional water supply should arise. Integrated water resources management can provide a realistic framework for examining the feasibility of water reuse. This paper evaluates how water reuse can become a strategic alternative in water resources management. The key challenges that limit water reclamation as one of the key elements in integrated water resources management scheme are discussed, including limitations with typical centralized wastewater treatment systems and public health protection, particularly the implications of trace contaminants. The key considerations to address these challenges are presented including (1) selection of appropriate treatment processes and reuse applications, (2) scientific and engineering solutions to emerging concerns, (3) consideration for cost effective and sustainable system, and (4) public acceptance. Recent water reclamation projects are presented to illustrate the response of the engineering community to the challenges of making water reclamation and reuse a real and sustainable solution to water supply system management planning. -

Sustainable Action Plan for County Operations 4890-012418 RTP-HT Table of Contents

REPORT CARD: FY 2016/2017 Sustainable Action Plan for County Operations 4890-012418 RTP-HT Table of contents Table of contents . 3 . Report card: FY 2016/2017 . 4 . How to use this report . 4 Progress summary . 5. Chapter 1 Chapter 4 Chapter 7 Minimizing the Carbon Footprint Alternative Fuel Waste of County Operations 6 Vehicles 12 Reduction 18 Noteworthy accomplishments . 6 Noteworthy accomplishments . 12 Noteworthy accomplishments . 18 Benefits & Performance . 7 Benefits & Performance . 13 Benefits & Performance . 19 Chapter 2 Chapter 5 Chapter 8 Renewable Energy & Energy Water Conservation Green Efficiency 8 & Management 14 Purchasing 20 Noteworthy accomplishments . 8 Noteworthy accomplishments . 14 Noteworthy accomplishments . 20 Benefits & Performance . 9 Benefits & Performance . 15 Benefits & Performance . 21 Chapter 3 Chapter 6 Chapter 9 Green Land Conservation Health & Building 10 & Management 16 Wellness 22 Noteworthy accomplishments . 10 Noteworthy accomplishments . 16 Noteworthy accomplishments . 22 Benefits & Performance . 11 Benefits & Performance . 17 Benefits & Performance . 23 Glossary . 24 References . 26 . Sustainable Action Plan for County Operations • Report Card: FY 2016/2017 | 3 REPORT CARD: FY 2016/2017 Sustainable Action Plan for County Operations n May 17, 2014, the Pima County Board of Supervisors adopted the 2014 Sustainable O Action Plan for County Operations . This plan seeks to achieve a “balance between economic development, social well-being and environmental protection to ensure the needs of current generations can be met without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs .” Measuring progress is crucial to the success of Pima County’s sustainability efforts . The purpose of this report card is to inform County decision makers and the broader community about Pima Construction workers restore and preserve the Pima County’s progress toward meeting the goals and County Historic Courthouse . -

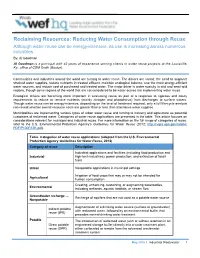

Reclaiming Resources: Reducing Water Consumption Through Reuse

Reclaiming Resources: Reducing Water Consumption through Reuse Although water reuse can be energy-intensive, its use is increasing across numerous industries By: Al Goodman Al Goodman is a principal with 42 years of experience serving clients in water reuse projects at the Louisville, Ky., office of CDM Smith (Boston). Communities and industries around the world are turning to water reuse. The drivers are varied: the need to augment strained water supplies, reduce nutrients in treated effluent, maintain ecological balance, use the most energy-efficient water sources, and reduce cost of purchased and treated water. The major driver is water scarcity in arid and semi-arid regions, though some regions of the world that are not considered to be water-scarce are implementing water reuse. Ecological drivers are becoming more important in evaluating reuse as part of a response to rigorous and costly requirements to reduce or remove nutrients (mainly nitrogen and phosphorus) from discharges to surface waters. Though water reuse can be energy-intensive, depending on the level of treatment required, only a full life-cycle analysis can reveal whether overall resource costs are greater than or less than alternative water supplies. Municipalities are implementing various types of urban water reuse and turning to industry and agriculture as potential customers of reclaimed water. Categories of water reuse applications are presented in the table. This article focuses on considerations relevant for municipal and industrial reuse. For more information on the full range of categories of reuse, refer to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Guidelines for Water Reuse (2012; http://nepis.epa.gov/Adobe/ PDF/P100FS7K.pdf). -

Quantifying the Potential of Renewable Natural Gas to Support a Reformed Energy Landscape: Estimates for New York State

energies Review Quantifying the Potential of Renewable Natural Gas to Support a Reformed Energy Landscape: Estimates for New York State Stephanie Taboada 1,2, Lori Clark 2,3, Jake Lindberg 1,2, David J. Tonjes 2,3,4 and Devinder Mahajan 1,2,* 1 Department of Materials Science and Chemical Engineering, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794, USA; [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (J.L.) 2 Institute of Gas Innovation and Technology, Advanced Energy Research and Technology, Stony Brook, NY 11794, USA; [email protected] (L.C.); [email protected] (D.J.T.) 3 Department of Technology and Society, Stony Brook University, 100 Nicolls Rd, Stony Brook, NY 11794, USA 4 Waste Data and Analysis Center, Stony Brook University, 100 Nicolls Rd, Stony Brook, NY 11794, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Public attention to climate change challenges our locked-in fossil fuel-dependent energy sector. Natural gas is replacing other fossil fuels in our energy mix. One way to reduce the greenhouse gas (GHG) impact of fossil natural gas is to replace it with renewable natural gas (RNG). The benefits of utilizing RNG are that it has no climate change impact when combusted and utilized in the same applications as fossil natural gas. RNG can be injected into the gas grid, used as a transportation fuel, or used for heating and electricity generation. Less common applications include utilizing RNG to produce chemicals, such as methanol, dimethyl ether, and ammonia. The GHG impact should be quantified before committing to RNG. This study quantifies the potential production of biogas (i.e., Citation: Taboada, S.; Clark, L.; the precursor to RNG) and RNG from agricultural and waste sources in New York State (NYS). -

Water Reclamation for Direct Re-Use in Urban and Industrial Applications in South Africa and Its Projected Impact Upon Water Demand

Water Reclamation for Direct Re-Use in Urban and Industrial Applications in South Africa and its Projected Impact Upon Water Demand A Grobicki • B Cohen Report to the Water Research Commission by Abbott Grobicki (Pty) Ltd r WRC Report No KV118/99 -^r -^r -^r *^^ Disclaimer This report emanates from a project financed by ihe Waler Research Commission (WRC) and is approved for publication. Approval docs not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of the WRC or the members of the project steering committee, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation tor use. Vrywaring Hierdie verslag spruit voort uit 'n navorsingsprojek wat deur die Waternavorsingskommissic (WNK) gefinansier is en goedgekeur is vir publikasie. Goedkeuring beteken nie noodwendig dat die inhoud die sicning en beleid van die WNK of die lede van die projek-loodskomitee weerspieel nie, of dat melding van handelsname of -ware deur die WNK vir gebruik goedgekeur n( aanbeveel word nie. WATER RECLAMATION FOR DIRECT RE-USE IN URBAN AND INDUSTRIAL APPLICATIONS IN SOUTH AFRICA, AND ITS PROJECTED IMPACT UPON WATER DEMAND A STUDY FOR THE WATER RESEARCH COMMISSION BY DR ANIA GROBICKI AND DR BRETT COHEN Abbott Grobicki (Pty) Ltd Kimberley House 34 Shortmarket Street 8001 Cape Town Tel: (021) 424-3892, Fax: (021) 424-3895 email: [email protected] OCTOBER 1998 ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Water reclamation, or the direct use of treated sewage effluent to replace a proportion of the fresh water demand, is regarded as a non-conventional approach to water management. However, water reclamation is becoming increasingly common internationally, especially in countries which have water shortages similar to that in South Africa. -

Reclaimed Municipal Wastewater for the Production of Bioenergy in The

Reclaimed Municipal Wastewater for the Production of Bioenergy in the United States — A Resource Assessment May Wu,* Miae Ha, and Yi-wen Chiu Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL *[email protected] ABSTRACT The production of bioenergy requires a significant amount of freshwater to be withdrawn and consumed to irrigate conventional crops and be used in the conversion process in the biorefinery. Reclaimed wastewater has long been seen as an alternative to water and nutrient sources because it contains low levels of nitrogen and phosphorus. In drought-prone areas in the Western United States, reclaimed wastewater has been widely used to irrigate agricultural crops. The key issue in developing bioenergy feedstock is to consider the reuse of reclaimed wastewater to reduce the need for freshwater. This study assesses the large-scale potential for using reclaimed wastewater as the resource for biofuel feedstock production in the United States. Geospatial analysis was applied to estimate reuse potential at the county level. Technical and infrastructural challenges are highlighted. KEY WORDS: Reclaimed municipal wastewater, effluent, discharge, irrigation, bioenergy INTRODUCTION It is anticipated that the demand for freshwater for producing food and energy and meeting basic human needs will continue to grow as the world’s population increases and people’s economic status improves. Enabling the long-term viability of the energy system thus requires the development of energy resources that protect natural resources and achieve environmental sustainability. The production of bioenergy (particularly with regard to conventional starch- based or oil-seed-based feedstock, such as corn or soybeans) requires a significant amount of freshwater to be withdrawn and consumed for irrigation (USDA 2008). -

Methodology for Use of Reclaimed Water at Federal Locations Source: Scott Clark Source: Fort Carson Golf Course, Irrigated with Reclaimed Water

FEDERAL ENERGY MANAGEMENT PROGRAM Methodology for Use of Reclaimed Water at Federal Locations Source: Scott Clark Source: Fort Carson Golf Course, irrigated with reclaimed water. The supply of freshwater has become a Water can be reused in three main ways: There are other legislative acts that Federal resource of concern on a global scale, 1. Water Recycle: Discharge water sites must comply with that do not delineate whether because of future availability or from an application or process is water reuse as a water source. To learn projected economic reasons. In response used again in the same application, more about these policies, visit the FEMP to this expanding problem, the United website for additional reference documents such as recycling the final laundry States Federal Government requires the to help facilitate meeting the water-related rinse water for the next cycle. reduction of water consumed by domestic, goals. industrial, landscaping and agricul- 2. On-site Water Reuse: Discharge www.femp.energy.gov/program/ tural needs at Federal sites. Executive water from one application or waterefficiency.html Order 13514 Federal Leadership in process that is captured, minimally Environmental, Energy, and Economic treated, and is utilized in another Performance directs Federal agencies to application. Examples include gray The steps covered in this fact sheet identify, promote and implement water water(1) reused for toilet or urinal were developed based on information reuse strategies consistent with state laws flushing. that reduce water consumption. Reusing gathered from the EPA Guidelines for (2) water is a large untapped alternative water 3. Water Reclaim: Also termed, Water Reuse . -

Water Reuse in Bioenergy Production – a Pathway to Conservation and Resiliency

WATER REUSE IN BIOENERGY PRODUCTION – A PATHWAY TO CONSERVATION AND RESILIENCY erhtjhtyhy MAY WU Argonne National Laboratory Water Reuse Webinar WaterReuse Association May 12, 2021 ENERGY — WATER NEXUS . Energy generation and water consumption are intertwined. Producing and transporting water requires energy; generating energy requires water for processing, cooling, and steam. Bioenergy production relies on water and energy input and requires land use. As technology advances, the industry is experiencing a revolutionary shift towards the biorefining of a broader range of products for affordable biofuels, bioproducts, and biopower. Extensive efforts have been devoted to increase energy efficiency, reduce energy use, and improve water conservation. 2 Source: https://www.energy.gov/energy-water-nexus-crosscut 3 Source: EIA TOTAL ETHANOL FUEL PRODUCTION AND CONSUMPTION: 2000 — 2019 . US produced 15,776 million gallons of ethanol, consumes 14,356 million gallons in 2019. RFS mandate 15,000 million gallons of conventional ethanol. The use of ethanol as a gasoline additive increased in an accelerating fashion from 2000 to 2010. Source: https://afdc.energy.gov/data/10323 5 MOTOR GASOLINE CONSUMPTION AND BIOFUEL BLENDING . According to EIA, in 2019, Americans used about 142 billion gallons of motor gasoline—or about 390 million gallons per day—and about 197 million gallons of aviation gasoline. Starting in 2010, E10 was sold in all 50 states to boost octane, meet air quality requirements. Ethanol is also available as E15 for use in light-duty vehicles of the model year 2001 and newer. Source: Decision Innovation Solutions, http://www.decision-innovation.com/ 6 ALTERNATIVE FUEL AND ELECTRIC VEHICLES Light-duty alternative fuel vehicles (AFVs), hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), and diesel models offered by vehicle manufacturers . -

Industrial Ecology

Industrial Ecology Fall 2010 • Management Orit Ofri • Business Administration Jennifer Howard-Grenville • Assistant Professor • Management Acknowledgements Special thanks to Annie Gorski from the City of Salem for her time and attention. Many thanks to the following: Stephanie Eisner, Willow Lake Water Pollution Control Facility, City of Salem Tyson Keever, SeQuential-Pacific Biodiesel Mark Steele, NORPAC Tory Banford, City of Salem John Wales, City of Salem 2 About SCI The Sustainable Cities Initiative (SCI) is a cross-disciplinary organization at the University of Oregon that seeks to promote education, service, public outreach, and research on the design and development of sustainable cities. We are redefining higher education for the public good and catalyzing community change toward sustainability. Our work addresses sustainability at multiple scales and emerges from the conviction that creating the sustainable city cannot happen within any single discipline. SCI is grounded in cross-disciplinary engagement as the key strategy for solving community sustainability issues. We serve as a catalyst for expanded research and teaching, and market this expertise to scholars, policymakers, community leaders, and project partners. Our work connects student energy, faculty experience, and community needs to produce innovative, tangible solutions for the creation of a sustainable society. About SCY The Sustainable City Year (SCY) program is a year-long partnership between SCI and one city in Oregon, in which students and faculty in courses from across the university collaborate with the partner city on sustainability and livability projects. SCY faculty and students work in collaboration with staff from the partner city through a variety of studio projects and service-learning courses to provide students with real-world projects to investigate. -

Reclaimed Water, Pelletization of Biosolids, and Biogas to Energy

FWRJ The Sustainability “Hat Trick”: Reclaimed Water, Pelletization of Biosolids, and Biogas To Energy Stephen McGrew and Diana Rivera he Palm Beach County Water Utilities Palm Beach County has a mandatory re- Department (utility) will become one claimed water service area that is strategi- Stephen McGrew, P.E., is plant design Tof the few utilities to complete the cally located to recharge wellfields, providing manager, and Diana Rivera, P.E., is project "hat trick" of recycling wastewater effluent, sustainability to the surficial aquifer. manager with Palm Beach County Water biosolids, and biogas when the biogas recip- Biosolids are pelletized for soil supplement Utilities Department. rocal engine generator sets complete opera- as a long-term sustainable disposal method tional testing in April of 2013 at the under an agreement with the Palm Beach Southern Region Water Reclamation Facility County Solid Waste Authority. The facility’s (facility). The utility is a leader in becoming biogas project, which is under construction, secondary effluent water. Additionally, a green utility and has adopted the mission is partially funded by green stimulus funds. nanofiltration membrane concentrate is statement, "Best Water, Best Customer Serv- The project includes two methane gas recip- used for blending with reclaimed water at the ice, and Best Environmental Stewardship." rocal engine generator sets installed at the fa- facility to supplement demand. The foundation of becoming a green utility cility in 2012. Reciprocal engines were The facility was completed in 1991 to is reduction of its environmental footprint chosen over fuel cells or gas turbines due to replace several smaller wastewater treatment through conservation, sustainability, energy their reliability and cost. -

Wastewater Reclamation and Biofuel Production Using Algae

Wastewater Reclamation and Biofuel Production Using Algae Tryg Lundquist, Ph.D., P.E., Presenter Ian Woertz, Matt Hutton, Ruth Spierling, Shelley Blackwell, Braden Crowe California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo, California MicroBio Engineering, Inc. San Luis Obispo, California Bioenergy | June 24, 2015 | Washington DC 1 Cal Poly Algae Technology Group Recent Major Projects • 2014 US DOE Algae Biomass Yield Project • 2013 US DOE Water & Nutrient Recycling Project • 2013 US DOE ATP3 Testbed Site (Prime: ASU) • 2011 CEC Algae Biofuels & Wastewater Reclamation • Investigators from: – Engineering – Chemistry – Microbiology – Animal nutrition – Natural Resources – Food science 2 Cal Poly is an ATP3 testbed site in ASU network. ATP3 has been a very fruitful project: Harmonization of production, lab standardization, and great collaboration. Site of DOE Project with Cal Poly & MicroBio Algae Wastewater Treatment Plant Biofuel Plant Paddle wheels Two 14,000 m2 paddle wheel mixed raceways 4 5 Wastewaters (WW) contain hazards but also resources… 6 Beyond protecting environmental water quality, the goals of wastewater treatment are to ... Recycle water Recover nutrients Produce biofuels 7 RNEW® Technology Recycle Nutrients Energy Water • CO2 addition to allow complete nutrient removal • Harvesting by bioflocculation • Low cost • Low energy intensity vs. conventional treatment • Biofuel via digestion or hydrothermal liquefaction 8 Full-scale raceway systems in California, Israel, S. Africa, New Zealand (but not designed for nutrient