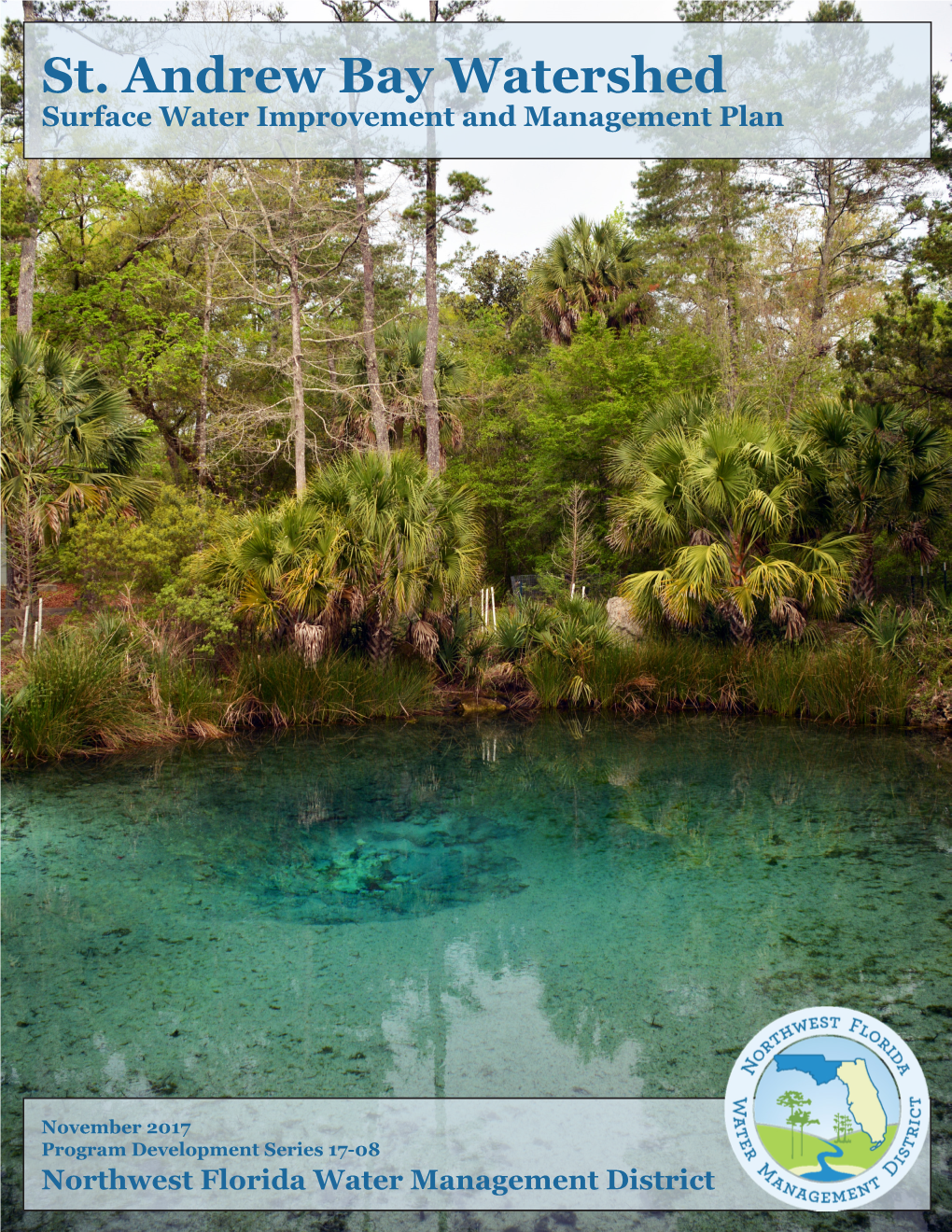

St. Andrew Bay Watershed Surface Water Improvement and Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Final St. Andrew Bay Characterization

1004401.0003.04 Draft St. Andrew Bay Watershed Characterization December 2016 Prepared by: St. Andrew Bay Watershed Characterization Northwest Florida Water Management District December 5, 2016 DRAFT WORKING DOCUMENT This document was developed in support of the Surface Water Improvement and Management Program with funding assistance from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s Gulf Environmental Benefit Fund. ii St. Andrew Bay Watershed Characterization Northwest Florida Water Management District December 5, 2016 DRAFT WORKING DOCUMENT Version History Location(s) in Date Version Summary of Revision(s) Document 6/28/2016 1 All Initial draft Watershed Characterization (Sections 1, 2, 3, 4, and 6) submitted to NWFWMD. 7/14/2016 2 Throughout Numerous edits and comments from District staff 11/18/2016 3 Throughout Numerous revisions to address District comments. 11/23/2016 4 Throughout Numerous edits and comments from District staff 12/5/2016 5 Throughout Numerous revisions to address District comments. L:\Publications\4200-4499\4401-0001_NWFWD iii St. Andrew Bay Watershed Characterization Northwest Florida Water Management District December 5, 2016 DRAFT WORKING DOCUMENT This page intentionally left blank. iv St. Andrew Bay Watershed Characterization Northwest Florida Water Management District December 5, 2016 DRAFT WORKING DOCUMENT Table of Contents Section Page 1.0 Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 SWIM Program Background, Goals, and Objectives...........................................1 -

Sampling and Analysis of Lakes in the Corangamite CMA Region (2)

Sampling and analysis of lakes in the Corangamite CMA region (2) Report to the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority CCMA Project WLE/42-009: Client Report 4 Annette Barton, Andrew Herczeg, Jim Cox and Peter Dahlhaus CSIRO Land and Water Science Report xx/06 December 2006 Copyright and Disclaimer © 2006 CSIRO & Corangamite Catchment Management Authority. To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO Land and Water or the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority. Important Disclaimer: CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. From CSIRO Land and Water Description: Rocks encrusted with salt crystals in hyper-saline Lake Weering. Photographer: Annette Barton © 2006 CSIRO ISSN: 1446-6171 Report Title Sampling and analysis of the lakes of the Corangamite CMA region Authors Dr Annette Barton 1, 2 Dr Andy Herczeg 1, 2 Dr Jim Cox 1, 2 Mr Peter Dahlhaus 3, 4 Affiliations/Misc 1. -

National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands 1996

National List of Vascular Plant Species that Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary Indicator by Region and Subregion Scientific Name/ North North Central South Inter- National Subregion Northeast Southeast Central Plains Plains Plains Southwest mountain Northwest California Alaska Caribbean Hawaii Indicator Range Abies amabilis (Dougl. ex Loud.) Dougl. ex Forbes FACU FACU UPL UPL,FACU Abies balsamea (L.) P. Mill. FAC FACW FAC,FACW Abies concolor (Gord. & Glend.) Lindl. ex Hildebr. NI NI NI NI NI UPL UPL Abies fraseri (Pursh) Poir. FACU FACU FACU Abies grandis (Dougl. ex D. Don) Lindl. FACU-* NI FACU-* Abies lasiocarpa (Hook.) Nutt. NI NI FACU+ FACU- FACU FAC UPL UPL,FAC Abies magnifica A. Murr. NI UPL NI FACU UPL,FACU Abildgaardia ovata (Burm. f.) Kral FACW+ FAC+ FAC+,FACW+ Abutilon theophrasti Medik. UPL FACU- FACU- UPL UPL UPL UPL UPL NI NI UPL,FACU- Acacia choriophylla Benth. FAC* FAC* Acacia farnesiana (L.) Willd. FACU NI NI* NI NI FACU Acacia greggii Gray UPL UPL FACU FACU UPL,FACU Acacia macracantha Humb. & Bonpl. ex Willd. NI FAC FAC Acacia minuta ssp. minuta (M.E. Jones) Beauchamp FACU FACU Acaena exigua Gray OBL OBL Acalypha bisetosa Bertol. ex Spreng. FACW FACW Acalypha virginica L. FACU- FACU- FAC- FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acalypha virginica var. rhomboidea (Raf.) Cooperrider FACU- FAC- FACU FACU- FACU- FACU* FACU-,FAC- Acanthocereus tetragonus (L.) Humm. FAC* NI NI FAC* Acanthomintha ilicifolia (Gray) Gray FAC* FAC* Acanthus ebracteatus Vahl OBL OBL Acer circinatum Pursh FAC- FAC NI FAC-,FAC Acer glabrum Torr. FAC FAC FAC FACU FACU* FAC FACU FACU*,FAC Acer grandidentatum Nutt. -

Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COLA

Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COL Application Part 2 — FSAR SUBSECTION 2.4.1: HYDROLOGIC DESCRIPTION TABLE OF CONTENTS 2.4 HYDROLOGIC ENGINEERING ..................................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1 HYDROLOGIC DESCRIPTION ............................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1.1 Site and Facilities .....................................................................2.4.1-1 2.4.1.2 Hydrosphere .............................................................................2.4.1-3 2.4.1.3 References .............................................................................2.4.1-12 2.4.1-i Revision 6 Turkey Point Units 6 & 7 COL Application Part 2 — FSAR SUBSECTION 2.4.1 LIST OF TABLES Number Title 2.4.1-201 East Miami-Dade County Drainage Subbasin Areas and Outfall Structures 2.4.1-202 Summary of Data Records for Gage Stations at S-197, S-20, S-21A, and S-21 Flow Control Structures 2.4.1-203 Monthly Mean Flows at the Canal C-111 Structure S-197 2.4.1-204 Monthly Mean Water Level at the Canal C-111 Structure S-197 (Headwater) 2.4.1-205 Monthly Mean Flows in the Canal L-31E at Structure S-20 2.4.1-206 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Canal L-31E at Structure S-20 (Headwaters) 2.4.1-207 Monthly Mean Flows in the Princeton Canal at Structure S-21A 2.4.1-208 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Princeton Canal at Structure S-21A (Headwaters) 2.4.1-209 Monthly Mean Flows in the Black Creek Canal at Structure S-21 2.4.1-210 Monthly Mean Water Levels in the Black Creek Canal at Structure S-21 2.4.1-211 NOAA -

Groundcover Restoration in Forests of the Southeastern United States

Groundcover RestorationIN FORESTS OF THE SOUTHEASTERN UNITED STATES Jennifer L. Trusty & Holly K. Ober Acknowledgments The funding for this project was provided by a cooperative • Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission of resource managers and scientific researchers in Florida, • Florida Department of Environmental Protection Conserved Forest Ecosystems: Outreach and Research • Northwest Florida Water Management District (CFEOR). • Southwest Florida Water Management District • Suwannee River Water Management District CFEOR is a cooperative comprised of public, private, non- government organizations, and landowners that own or We are grateful to G. Tanner for making the project manage Florida forest lands as well as University of Florida possible and for providing valuable advice on improving the faculty members. CFEOR is dedicated to facilitating document. We are also indebted to the many restorationists integrative research and outreach that provides social, from across the Southeast who shared information with J. ecological, and economic benefits to Florida forests on a Trusty. Finally, we thank H. Kesler for assistance with the sustainable basis. Specifically, funding was provided by maps and L. DeGroote, L. Demetropoulos, C. Mackowiak, C. Matson and D. Printiss for assistance with obtaining photographs. Cover photo: Former slash pine plantation with restored native groundcover. Credits: L. DeGroote. Suggested citation: Trusty, J. L., and H. K. Ober. 2009. Groundcover restoration in forests of the Southeastern United States. CFEOR Research Report 2009-01. University of Florida, Gainesville, FL. 115 pp. | 3 | Table of Contents INTRODUCTION . 7 PART I - Designing and Executing a Groundcover PART II – Resources to Help Get the Job Done Restoration Project CHAPTER 6: Location of Groundcover CHAPTER 1: Planning a Restoration Project . -

Pine Log State Forest Management Plan

TEN-YEAR RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE PINE LOG STATE FOREST BAY AND WASHINGTON COUNTIES PREPARED BY FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE AND CONSUMER SERVICES DIVISION OF FORESTRY APPROVED ON APRIL 28, 2010 PINE LOG STATE FOREST TEN YEAR RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................................... 1 I. INTRODUCTION A. General Mission, Goals for Florida State Forest and Management Plan Direction ......................................... 2 B. Overview of State Forest Management Program ............................................................................................. 2 C. Past Accomplishments .................................................................................................................................... 3 D. Goals/Objectives for the Next Ten Year Period .............................................................................................. 3 E. Management Needs, Priority Schedule and Cost Estimates ............................................................................ 6 II. ADMINISTRATIVE SECTION A. Descriptive Information ................................................................................................................................ 9 1. Common Name of Property .................................................................................................................. 9 2. Location, Boundaries and Improvements .............................................................................................. -

Best Ra Rates in Florida

December 2004, premier edition Everything Equine Free The newest and soonHorses to be For number Sale one sales magazineStud in Services SW Florida Boarding Stables Trucks & Trailers BEST RATES Feed Stores IN FLORIDA Trainers Veterinarians Farriers Tack and MORE! Advertising everything under the Florida sun that a horse owner could possibly need or want. Page 2 Everything Equine December 2004 [email protected] 239-403-3784 Everything Equine Browse by County: Charlotte & Sumter 18-19 Office Phone 239-403-3784 Collier 3-12, 18, 24 [email protected] Lee 14, 15 Sales: Jennifer Orfely Special Features: 239-571-6964cell Horse Hair Jewelry Graphics: 12-13 Melody Halperin 239-370-5945cell Mailing Address: 460 6th St NE Naples, FL 34120 Florida Trails 20 Comments and/or suguesstions are welcome! Trail Trotter 11-12 Subscriptions are available, please contact us directly. We have made every attempt to ensure that the At Your Fingertips: content is free from errors. If you feel an error has been made, please bring it to our attention. Calendar 17 We do not endorse and are not responsible for the validity or quality of products and services Resource Directory 22 advertised or items placed for sale. To All Our Advertisers... Richard M. DeVos couldn’t have stated it any better when he said, “The only thing that stands between a man and what he wants from life is often merely the will to try it, and the faith to believe that it is possible.” We at Everything Equine would like to express our sincere thanks and gratitude to all of you who believed in us enough to advertise on our first issue. -

Macbridea Alba

Macbridea alba (White birds-in-a-nest) 5-Year Review: Summary and Evaluation Lathrop Management Area, Bay County. Photos by Vivian Negrón-Ortiz U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Panama City Field Office Panama City, Florida 5-YEAR REVIEW Macbridea alba (White birds-in-a-nest) I. GENERAL INFORMATION A. Methodology used to complete the review This review was accomplished using information obtained from the plant’s 1994 Recovery Plan, peer reviewed scientific publications, unpublished field survey results, reports of current research projects, unpublished field observations by Service, State and other experienced biologists, and personal communications. These documents are on file at the Panama City Field Office. A Federal Register notice announcing the review and requesting information was published on April 16, 2008 (73 FR 20702). Comments received and suggestions from peer reviewers were evaluated and incorporated as appropriate (see appendix A). No part of this review was contracted to an outside party. This review was completed by the Service’s lead Recovery botanist in the Panama City Field Office, Florida. B. Reviewers Lead Field Office: Dr. Vivian Negrón-Ortiz, Panama City Field Office, 850-769-0552 ext. 231, [email protected] Lead Region: Southeast Region: Kelly Bibb, 404-679-7132 Peer reviewers: Ms. Louise Kirn, District Ecologist Apalachicola National Forest P.O. Box 579, Bristol, FL 32321 Ms. Faye Winters, Field Office Biologist BLM Jackson Field Office 411 Briarwood Drive, Suite 404 Jackson, MS 39206 C. Background 1. FR Notice citation announcing initiation of this review: 73 FR 20702 (April 16, 2008). 1 2. Species status: Unknown (Recovery Data Call 2008); the species status is unknown until all the Element Occurrences1 (EO’s) are revisited. -

Class G Tables of Geographic Cutter Numbers: Maps -- by Region Or

G3862 SOUTHERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3862 FEATURES, ETC. .C55 Clayton Aquifer .C6 Coasts .E8 Eutaw Aquifer .G8 Gulf Intracoastal Waterway .L6 Louisville and Nashville Railroad 525 G3867 SOUTHEASTERN STATES. REGIONS, NATURAL G3867 FEATURES, ETC. .C5 Chattahoochee River .C8 Cumberland Gap National Historical Park .C85 Cumberland Mountains .F55 Floridan Aquifer .G8 Gulf Islands National Seashore .H5 Hiwassee River .J4 Jefferson National Forest .L5 Little Tennessee River .O8 Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail 526 G3872 SOUTHEAST ATLANTIC STATES. REGIONS, G3872 NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. .B6 Blue Ridge Mountains .C5 Chattooga River .C52 Chattooga River [wild & scenic river] .C6 Coasts .E4 Ellicott Rock Wilderness Area .N4 New River .S3 Sandhills 527 G3882 VIRGINIA. REGIONS, NATURAL FEATURES, ETC. G3882 .A3 Accotink, Lake .A43 Alexanders Island .A44 Alexandria Canal .A46 Amelia Wildlife Management Area .A5 Anna, Lake .A62 Appomattox River .A64 Arlington Boulevard .A66 Arlington Estate .A68 Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial .A7 Arlington National Cemetery .A8 Ash-Lawn Highland .A85 Assawoman Island .A89 Asylum Creek .B3 Back Bay [VA & NC] .B33 Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge .B35 Baker Island .B37 Barbours Creek Wilderness .B38 Barboursville Basin [geologic basin] .B39 Barcroft, Lake .B395 Battery Cove .B4 Beach Creek .B43 Bear Creek Lake State Park .B44 Beech Forest .B454 Belle Isle [Lancaster County] .B455 Belle Isle [Richmond] .B458 Berkeley Island .B46 Berkeley Plantation .B53 Big Bethel Reservoir .B542 Big Island [Amherst County] .B543 Big Island [Bedford County] .B544 Big Island [Fluvanna County] .B545 Big Island [Gloucester County] .B547 Big Island [New Kent County] .B548 Big Island [Virginia Beach] .B55 Blackwater River .B56 Bluestone River [VA & WV] .B57 Bolling Island .B6 Booker T. -

Seagrass Integrated Mapping and Monitoring for the State of Florida Mapping and Monitoring Report No. 1

Yarbro and Carlson, Editors SIMM Report #1 Seagrass Integrated Mapping and Monitoring for the State of Florida Mapping and Monitoring Report No. 1 Edited by Laura A. Yarbro and Paul R. Carlson Jr. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Fish and Wildlife Research Institute St. Petersburg, Florida March 2011 Yarbro and Carlson, Editors SIMM Report #1 Yarbro and Carlson, Editors SIMM Report #1 Table of Contents Authors, Contributors, and SIMM Team Members .................................................................. 3 Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... 5 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. 7 Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 31 How this report was put together ........................................................................................... 36 Chapter Reports ...................................................................................................................... 41 Perdido Bay ........................................................................................................................... 41 Pensacola Bay ..................................................................................................................... -

Friends of Perdido Bay ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED 10738 Lillian Highway Pensacola, FL 32506 850-453-5488

Bulk Rate U.S. Postage Paid Permit No. 1013 Foley, AL 36535 Friends of Perdido Bay ADDRESS SERVICE REQUESTED 10738 Lillian Highway Pensacola, FL 32506 850-453-5488 Tidings The Newsletter of the Friends of Perdido Bay . July/August 2012 Volume 25 Number 4 Jackie Lane - Editor www.friendsofperdidobay.com What A Difference Dilution Makes With the deluge the Pensacola area experienced on June 9th, the drought that was plaguing this area, was finally broken in a big way. Thirteen to 20 inches fell in one day at certain areas close to the bay. Less rain fell in the northern part of the watershed. The few rains we have had this past Spring were not really sufficient to break the year long drought. Before the June 9th rain, the Perdido River was at very low flow. Any type of man-made pollution entering Perdido Bay would not get sufficient dilution and toxic substances (what ever they are) would increase in the bay. This is especially true of paper mill effluent from International Paper, which during times of low flow of the Perdido River, can constitute one-fifth of the flow of the Perdido River. Because of the very concentrated pollution of paper mill effluent, especially high levels of organic chemicals and organic nitrogen, paper mill effluent needs to be greatly diluted in order not to cause harm. This spring there was a dearth of life in the bay. A 2-liter plastic bottle placed in the upper bay, had no barnacles growing on it after three weeks in the bay.