Appendix A: Comment Letters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ACT BART S Ites by Region.Csv TB1 TB6 TB4 TB2 TB3 TB5 TB7

Services Transit Outreach Materials Distribution Light Rail Station Maintenance and Inspection Photography—Capture Metadata and GPS Marketing Follow-Up Programs Service Locations Dallas, Los Angeles, Minneapolis/Saint Paul San Francisco/Oakland Bay Area Our Customer Service Pledge Our pledge is to organize and act with precision to provide you with excellent customer service. We will do all this with all the joy that comes with the morning sun! “I slept and dreamed that life was joy. I awoke and saw that life was service. I acted and behold, service was joy. “Tagore Email: [email protected] Website: URBANMARKETINGCHANNELS.COM Urban Marketing Channel’s services to businesses and organizations in Atlanta, Dallas, San Francisco, Oakland and the Twin Cities metro areas since 1981 have allowed us to develop a specialty client base providing marketing outreach with a focus on transit systems. Some examples of our services include: • Neighborhood demographic analysis • Tailored response and mailing lists • Community event monitoring • Transit site management of information display cases and kiosks • Transit center rider alerts • Community notification of construction and route changes • On-Site Surveys • Enhance photo and list data with geocoding • Photographic services Visit our website (www.urbanmarketingchannels.com) Contact us at [email protected] 612-239-5391 Bay Area Transit Sites (includes BART and AC Transit.) Prepared by Urban Marketing Channels ACT BART S ites by Region.csv TB1 TB6 TB4 TB2 TB3 TB5 TB7 UnSANtit -

SBC Executivesummfac

CAPITOL CORRIDOR SOUTH BAY CONNECT AUGUST 2020 Purpose Study Area and Project Elements South Bay Connect proposes to relocate the Capitol Corridor passenger rail service between the Oakland N Coliseum and Newark from the Union Pacific Railroad (UP) Niles Subdivision to the Coast Subdivision for a faster, more direct route. It will also create new transbay connections for passengers between the East Bay and Peninsula by connecting to bus and shuttle services at the Ardenwood Station. The project is not proposing an increase in Capitol Corridor service frequency or changes to UP’s freight service, but does not preclude service growth in the future. The relocation will facilitate the separation of passenger and freight rail, resulting in improved rail operations, efficiency, and reliability while minimizing rail congestion within the corridor. Proposed New Station and Railroad Potential Station Area Proposed Capitol Corridor (CC) Service Potential Station Considered and Eliminated Existing CC Service Existing Station CC Service to be Discontinued Station where CC Service Study Area to be Discontinued UP Improvement Area BART Station Benefits Reduce passenger rail travel time between Oakland and San Jose and throughout the larger megaregion to increase ridership on transit, ease congestion on the Bay Area’s stressed roadways, and decrease auto commutes. Diversify and enhance network integration by reducing duplicative capital investments and dif- ferentiating Capitol Corridor’s intercity rail service from commuter rail and other transit services, including BART’s extension to San Jose. Support economic vitality by permitting enhanced rail movement and the preservation of freight rail capacity in the Northern California market through the reduction of existing conflicts between freight rail operations and passenger rail service. -

Mcconaghy House Teacher Packet Contains Historical Information About the Mcconaghy Family, Surrounding Region, and American Lifestyle

1 WELCOME TO THE McCONAGHY HOUSE! Visiting the McConaghy House is an exciting field trip for students and teachers alike. Docent-led school tours of the house focus on local history, continuity and change, and the impact of individuals in our community. The house allows students to step into the past and experience and wonder about the life of a farming family. The McConaghy House is also an example of civic engagement as the community mobilized in the 1970’s to save the house from pending demolition. Through the efforts of concerned citizens, an important part of our local history has been pre- served for future generations to enjoy. The McConaghy House Teacher Packet contains historical information about the McConaghy family, surrounding region, and American lifestyle. Included are pre and post visit lesson plans, together with all necessary resources and background information. These lessons are not required for a guided visit but will greatly enrich the experience for students. The lessons can be completed in any order, though recommendations have been made for ease of implementation. We welcome comments and suggestions about the usefulness of this packet in your classroom. An evaluation form is enclosed for your feedback. Thank you for booking a field trip to the McConaghy House. We look forward to seeing you and your students! Sincerely, Education Department 22380 Foothill Blvd Hayward, CA 94541 510-581-0223 www.haywardareahistory.org 2 Table of Contents Teacher Information The Hayward Area Historical Society .................................................................................... 4 Why do we study history? How does a museum work? ....................................................... 5 History of the McConaghy Family for Teachers ................................................................... -

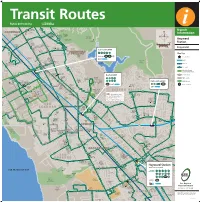

Hayward Transit Routes Map (PDF)

Verdese Carter Rec. Ctr. Snow Bldg. Elmhurst NX3 98 Comm. Prep Hellman Transit Park ELMHURST Holly Elmhurst- 40 NXC Mini- Lyons Field 75 Dunsmuir Information Elmhurst INTERNATIONALPark BLVD 57 Foothill Plaza Square 45 East Bay House & 1 0 6 T H A V M V Gardens Lake Chabot A A Reg’l Parks 9 8 T H A V 45 C H Municipal A 08T BANCROFT AV R 1 Hq Golf Course 98 T H UR Hayward 45 1 0 4 T H A V B NX4 Dunsmuir Ridge LV D 75 Open Space Clubhouse NXC 0 0.5mi Station Durant Stonehurst D Square L V V A D M B Victoria A Park O O O R REVE R E EDE 1 0 5 T H A V B R Park S A Roosevelt V 45 Plgd. Farrelly NX3 0 0.5km Hayward SAN LEANDRO BLVD 1 75 Shefeld 45 Pool Rec. Ctr. San Leandro BART N McCartney 75 Milford Park Park SHEFFIELD Tyrone D U T T O N A V 1 10 75 85 89 Carney 75 Onset A 40 VILLAGE Map Key Park C Park A Chabot L R A E E 1 4 T H S T Park Shuttles NL SL N N D E You Are Here S Vets. W D Siempre R O 75 Mem. G Verde Park O R BART D Bldg. A D 45 City N Willow Park BART Memorial R R CAPISTRANO DR D Hall Bancroft T D L A O Public R Park B C A L L A N A V A K D Root Library Mid. -

2015 Station Profiles

2015 BART Station Profile Study Station Profiles – Non-Home Origins STATION PROFILES – NON-HOME ORIGINS This section contains a summary sheet for selected BART stations, based on data from customers who travel to the station from non-home origins, like work, school, etc. The selected stations listed below have a sample size of at least 200 non-home origin trips: • 12th St. / Oakland City Center • Glen Park • 16th St. Mission • Hayward • 19th St. / Oakland • Lake Merritt • 24th St. Mission • MacArthur • Ashby • Millbrae • Balboa Park • Montgomery St. • Civic Center / UN Plaza • North Berkeley • Coliseum • Oakland International Airport (OAK) • Concord • Powell St. • Daly City • Rockridge • Downtown Berkeley • San Bruno • Dublin / Pleasanton • San Francisco International Airport (SFO) • Embarcadero • San Leandro • Fremont • Walnut Creek • Fruitvale • West Dublin / Pleasanton Maps for these stations are contained in separate PDF files at www.bart.gov/stationprofile. The maps depict non-home origin points of customers who use each station, and the points are color coded by mode of access. The points are weighted to reflect average weekday ridership at the station. For example, an origin point with a weight of seven will appear on the map as seven points, scattered around the actual point of origin. Note that the number of trips may appear underrepresented in cases where multiple trips originate at the same location. The following summary sheets contain basic information about each station’s weekday non-home origin trips, such as: • absolute number of entries and estimated non-home origin entries • access mode share • trip origin types • customer demographics. Additionally, the total number of car and bicycle parking spaces at each station are included for context. -

BART Hayward Station Closure Monday, February 6Th, 2017

BART Hayward Station Closure Monday, February 6th, 2017 5:04 PM There is a station closure and trains are holding out at Hayward station due to police activity. -- 6:00 PM There is a 10-minute delay between 24th St. Mission and Balboa Park on the Daly City Line in the SFO, Millbrae and East Bay directions due to an equipment problem on the track. There is a station closure and trains are holding out at Hayward station due to police activity. There is a major delay at Hayward on the Fremont Line in the Fremont, Richmond and Daly City directions due to police activity. Parallel service is available via AC Transit. Bus #10 between Hayward and Bayfair. Bus#99 from Hayward to South Hayward and beyond. -- 6:30 PM There is a 10-minute delay between 24th St. Mission and Balboa Park on the Daly City Line in the SFO, Millbrae and East Bay directions due to an equipment problem on the track. This advisory is sent in the event anyone is still in their office monitoring BART progress tonight. There is a station closure and trains are holding out at Hayward station due to police activity. There is a major delay at Hayward on the Fremont Line in the Fremont, Richmond and Daly City directions due to police activity. Parallel service is available via AC Transit. Bus #10 between Hayward and Bayfair. Bus#99 from Hayward to South Hayward and beyond. There is a major delay on the Richmond Line in the Fremont direction due to police activity. -

View Reducing Parking at Transit Stations

Rail~Volution Salt Lake City, Utah 8-10 September, 2005 Reducing Parking at Transit Stations Jeffrey Tumlin EVALUATING PARKING AT TRANSIT STATIONS • Effects on transit ridership – Transit Oriented Development (TOD): New households & transit trips – Parking: Park-&-Ride participants – Implications for encouraging future growth in ridership • Effects on traffic congestion – Walking, cycling & transit trips to station – Proportion and amount of vehicle trips to station – Implications in allocating of street right-of-way • Effects on revenue generation – Lease or sale of land: Land value with higher density & mixed use compared to parking – Development of land: Joint development, economic vitality – Productive use of land: Economic productivity, sales tax Reduced Transit Parking at Rail Stations Jeffrey Tumlin, Nelson\Nygaard Consulting STRATEGIES FOR REDUCING TRANSIT PARKING • SkyTrain system in Vancouver, BC (TransLink) – Land use concentration around SkyTrain – Transportation supply – Transportation demand including low to no parking • Metrorail stations in Arlington County, VA (WMATA) – Urban village development – Multimodal transportation – Shared parking only (No park-&-ride) • South Hayward station in Northern California (BART) – Plans to develop area around station and improve pedestrian, bicycle and bus access – Determining amount of replacement parking Reduced Transit Parking at Rail Stations Jeffrey Tumlin, Nelson\Nygaard Consulting TRANSLINK SKYTRAIN SYSTEM Reduced Transit Parking at Rail Stations Jeffrey Tumlin, Nelson\Nygaard Consulting Greater Vancouver Reduced Transit Parking at Rail Stations Canada – US BorderJeffrey Tumlin, Nelson\Nygaard Consulting Vancouver’s Regional Planning Context • GVTA Act – Support Livable Region Strategic Plan • Transport strategy aims to increase choice through 3 “levers” – Land use i.e. town centers, employment, , residential density – Transportation supply-side e.g rapid transit network – Transportation demand- side e.g. -

Transportation Demand Management Plan

SoHay Mixed Use Development Project Transportation Demand Management Plan Hayward, California February 28, 2018 SoHay Mixed Used Development Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................1 Project Trip Generation ........................................................................................................................1 Parking ...................................................................................................................................................2 Report Organization .............................................................................................................................3 Existing Transportation Facilities and Services ..................................................................................6 Transit Facilities .................................................................................................................................................................... 6 BART ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Bus Routes .............................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Bicycle Facilities ................................................................................................................................................................... -

It's a Crisp Morning at the Coyote Creek Field Station of the San

Blues, rock Four-legged Chanticleers and soul weed-whackers presents music provide ‘Dial M for headliners essential Murder’ come to services town Page 12 Page 19 Page 25 Scan for our FREE App or Search App Store for TCVnews 510-494-1999 [email protected] www.tricityvoice.com January 30, 2018 Vol. 16 No. 5 ARTICLE AND PHOTOS BY MARGARET THORNBERRY It’s a crisp morning at the Coyote Creek Field Station of the San Francisco Bay Bird Observatory (SFBBO), and the staff is bundled up and ready to move out to put up mist nets. The nets are a fine mesh, nearly invisible, but flexible and fine enough so that when a bird flies into them, it is held safely, ready to be carefully removed by hand, placed into a small cloth bag to calm it, and tucked under a jacket or shirt to keep warm for the walk back to the station office. There it is weighed, measured, evaluated for health and either banded, or if already banded, logged, and then carefully released. Continued on page 17 Banded Snowy Plover Photo by Ben Pearl signature outdoor activity program, its Trails Challenge. Launched in 1993 to get East Bay residents moving outdoors and exploring their trails, the program makes it easy for hikers of all abilities to get to know and love their Regional Parks. Trails Challenge is a free program supported through financial contributions from the East Bay Regional Park District, Kaiser Permanente, and SUBMITTED BY DAVE MASON the Regional Parks Foundation. PHOTOS COURTESY EBPRD “The 2017 Trails Challenge was great,” said Hayward resident and 2017 participant This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Diane Petersen. -

Bart at Twenty: Land Use and Development Impacts

ffional Development BART@20: Land Use and Development Impacts Robert Cervero with research assistance by Carlos Castellanos, Wicaksono Sarosa, and Kenneth Rich July 1995 University of California at Berkeley - 1 BART@20: Land Use and Development Impacts Robert Cervero with Research Assistance by Carlos Castellanos, Wicaksono Sarosa, and Kenneth Rich This paper was produced with support provided by the U.S. Department of Transportation and the California State Department of Transportation (Caltrans) through the University of California Transportation Center. University of California at Berkeley Institute of Urban and Regional Development Table of Contents ONE: BART at 20: An Analysis of Land Use Impacts 1 1. INTRODUCTION 1 TWO: Research Approach and Data Sources 3 THREE: Employment and Population Changes in BART and Non-BART Areas 6 3.1. Population Changes 6 3.2. Employment Changes 3.3. Population Densities 15 3.4. Employment Densities 15 3.5. Summary 20 FOUR: Land Use Changes Over Time and by Corridor 21 4.1. General Land-Use Trends 23 4.2. Pre-BART versus Post-BART 25 4.3. Early versus Later BART 30 4.4. Trends in Non-Residential Densities 33 4.4. Summary 37 FIVE: Land-Use Changes by Station Classes 38 5.1. Grouping Variables 38 5.2. Classification 38 5.3. Station Classes 41 5.4. Trends in Residential and Non-Residential Growth Among Station Classes 44 5.5. Percent Growth in Early- versus Later-BART Years Among Station Classes 46 5.6. Trends in Non-Residential Densities Among Station Classes 46 SLX: Matched-Pair Comparisons of Land-Use Changes near BART Stations Versus Freeway Interchanges 51 6.1. -

18-311 ,:/1 Meeting Date: December 12, 2018 Alameda-Contracosta Transit District

ReportNo: 18-311 ,:/1 Meeting Date: December 12, 2018 Alameda-ContraCosta Transit District STAFF RE PO RT TO: ACTransit Board of Directors FROM: Michael A. Hursh, General Manager SUBJECT: Operator Restroomsat BARTStations ACTION ITEM RECOMMENDED ACTION(S) Consider authorizing the GeneraIManager to negotiate and execute an agreement with the Bay Area RapidTransit District (BART)for the design, construction, operation, and maintenance of Operator restrooms. BUDGETARY/FISCAL IMPACT This project will be added to the current fiscal year Capital Budget and Capital Improvement Planwith $638,826 in District Capital funds. Capital Planning and Grants will continue to seek externalfunding to support this project. BACKGROUND/RATIONALE AC Transit provides fixed route serviceto and from many Bay Area RapidTransit District IBART) stations located in the East Bay.AC Transit Operators and Road Supervisors rely on the ability to utilize BART station restroom facilities during a scheduled break. On several occasions, employees were not able to use the public restrooms because of long lines or the restroom being closed for repairs. At the April 4, 2018 BART/AC Transit Interagency Liaison Committee jtLC) both agencies agreed to collaborate on developing a process to provide restroom access for AC Transit personnelat BARTstations. Station Restroom Assessment Staff conducted an assessmentof fourteen BART stations where AC Transit buses have scheduled layovers and are utilized by District employees for restroom breaks during the peak period between 3:00pm and 9:00pm. Listed on the table below are the BARTstations with the highest amount of buses scheduled for layover during the evening: 1 of 23 Report No. 18-311 Page2 of4 BARTStation LayoversPerPeak Period Fruitvale fremont Bay Fair West Oakland Coliseum EI Cerrito Plaza SanLeandro The following BARTstations were determined to be least utilized with lessthan 25 scheduled busesthat layover: DeINorte, South Hayward, Castro Valley, Richmond and North Berkeley. -

Reliability Centered Maintenance

MTI A Case Maintenance Optimal Study Railway of to Achieve Performance Transit Reliability Centered Maintenance: Funded by U.S. Department of A Case Study of Railway Transit Transportation and California Department of Transportation Maintenance to Achieve Optimal Performance MTI ReportMTI 10-06 MTI Report 10-06 October 2010 MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE MTI FOUNDER Hon. Norman Y. Mineta The Norman Y. Mineta International Institute for Surface Transportation Policy Studies (MTI) was established by Congress as part MTI BOARD OF TRUSTEES of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Efficiency Act of 1991. Reauthorized in 1998, MTI was selected by the U.S. Department of Transportation through a competitive process in 2002 as a national “Center of Excellence.” The Institute is funded by Con- Honorary Co-Chair Rebecca Brewster Steve Heminger Stephanie Pinson gress through the United States Department of Transportation’s Research and Innovative Technology Administration, the Califor- Hon. James Oberstar ** President/COO Executive Director President/COO nia Legislature through the Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and by private grants and donations. Chair American Transportation Metropolitan Transportation Gilbert Tweed Associates, Inc. House Transportation and Research Institute Commission New York, NY Smyrna, GA Oakland, CA Infrastructure Committee The Institute receives oversight from an internationally respected Board of Trustees whose members represent all major surface Hans Rat House of Representatives Donald H. Camph Hon. John Horsley # Secretary General transportation modes. MTI’s focus on policy and management resulted from a Board assessment of the industry’s unmet needs Washington, DC President Executive Director Union Internationale des and led directly to the choice of the San José State University College of Business as the Institute’s home.