Pasquia/Porcupine Integrated Forest Land Use Plan Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summary Report of the Geological Survey for the Calendar Year 1911

5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 SUMMARY REPORT OK THE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DEPARTMENT OF MINES FOR THE CALENDAR YEAR 1914 PRINTED BY ORDER OF PARLIAMENT. OTTAWA PRTNTKD BY J. i»k L TAOHE, PRINTER TO THE KING'S MOST EXCELLENT IfAJESTS [No. 26—1915] [No , 15031 5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 To Field Marshal, Hit Hoi/al Highness Prince Arthur William Patrick Albert, Duke of Connaught and of Strath-earn, K.G., K.T., K.P., etc., etc., etc., Governor General and Commander in Chief of the Dominion of Canada. May it Please Youb Royal Highness.,— The undersigned has the honour to lay before Your Royal Highness— in com- pliance with t>-7 Edward YIT, chapter 29, section IS— the Summary Report of the operations of the Geological Survey during the calendar year 1914. LOUIS CODERRK, Minister of Mines. 5 GEORGE V. SESSIONAL PAPER No. 26 A. 1915 To the Hon. Louis Codebrk, M.P., Minister of Mines, Ottawa. Sir,—I have the honour to transmit, herewith, my summary report of the opera- tions of the Geological Survey for the calendar year 1914, which includes the report* of the various officials on the work accomplished by them. I have the honour to be, sir, Your obedient servant, R. G. MrCOXXFI.L, Deputy Minister, Department of Mines. B . SESSIONAL PAPER No. 28 A. 1915 5 GEORGE V. CONTENTS. Paok. 1 DIRECTORS REPORT REPORTS FROM GEOLOGICAL DIVISION Cairncs Yukon : D. D. Exploration in southwestern "" ^ D. MacKenzie '\ Graham island. B.C.: J. M 37 B.C. -

APPENDIX 4-A Stakeholder and Aboriginal Organizations Record Of

S TAR-ORION S OUTH D IAMOND P ROJECT E NVIRONMENTAL I MPACT A SSESSMENT APPENDIX 4-A Stakeholder and Aboriginal Organizations Record of Contacts SX03733 – Section 4.0 Table 4-A.1 RECORDS OF CONTACT: GOVERNMENT CONTACTS (November 1, 2008 – November 30, 2010) Event Type Event Date Stakeholders Team Members Details Phone Call 19-Nov-08 Town of Choiceland, DDAC Julia Ewing Call to JE to tell her that the SUMA conference was going on at the exact same time as Shores proposed open houses and 90% of elected leadership would be away attending the conference in Saskatoon. Meeting 9-Dec-08 Economic Development Manager, City of Eric Cline; Julia Ewing Meeting at City Hall in Prince Albert. Prince Albert; Economic Development Coordinator, City of Prince Albert Meeting 11-Dec-08 Canadian Environmental Assessment Eric Cline; Julia Ewing; Meeting at Shore Gold Offices - Agency Ethan Richardson Review community engagement and Development Project Administrator, Ministry other EIA approaches with CEA and of Environment; MOE Director, Ministry of Environment; Senior Operational Officer, Natural Resources Canada; Environmental Project Officer, Ministry of Environment Letter sent 19-Jan-09 Acting Deputy Minister, Energy and Julia Ewing Invitation to Open House Resources, Government of Saskatchewan Letter sent 19-Jan-09 Deputy Minister, First Nations Métis Eric Cline Invitation to Open Houses Relations, Government of Saskatchewan Letter sent 19-Jan-09 Executive Director, First Nations Métis Eric Cline Invitation to Open Houses Relations Government of Saskatchewan Letter sent 19-Jan-09 Senior Consultation Advisor, Aboriginal Eric Cline Invitation to Open Houses Consultation, First Nations Métis Relations Government of Saskatchewan Phone Call 21-Jan-09 Canadian Environmental Assessment Eric Cline; Julia Ewing; Discuss with Feds and Prov, Shore's Agency; Ethan Richardson; Terri involvement in the consultation Development Project Administrator, Ministry Uhrich process for the EIA. -

SPATIAL DIFFUSION of ECONOMIC IMPACTS of INTEGRATED ETHANOL-CATTLE PRODUCTION COMPLEX in SASKATCHEWAN a Thesis Submitted To

SPATIAL DIFFUSION OF ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF INTEGRATED ETHANOL-CATTLE PRODUCTION COMPLEX IN SASKATCHEWAN A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Agricultural Economics University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon Emmanuel Chibanda Musaba O Copyright Emmanuel C. Musaba, 1996. All rights reserved. National Library Bibliotheque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Sewices services bibliographiques 395 WeIIington Street 395. rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your& vobrs ref6llBIlt8 Our & NomMhwm The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde me licence non exclusive licence dowing the exclusive pennettant a la National Library of Canada to Bibliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, preter' distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette these sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfichelf2m, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format electronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriete du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protege cette these. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celIe-ci ne doivent Stre imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN College of Graduate Studies and Research SUMMARY OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial ilfihent b of the requirements for the DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY EMMANUEL CHLBANDA MUSABA Department of AgricuIturd Economics CoUege of Agriculture University of Saskatchewan Examining Committee: Dr. -

Aboriginal Entrepreneurship in Forestry Proceedings of a Conference Held January 27-29, 1998, in Edmonton, Alberta

Aboriginal Entrepreneurship in Forestry Proceedings of a conference held January 27-29, 1998, in Edmonton, Alberta Conference sponsored by the First Nation Forestry Program, a ioint initiative of Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, and Indian and Northern AHairs Canada published by Canadian Forest Service Northern Forestry Centre, Edmonton 1998 ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 1998 This publication is available at no charge from: Natural Resources Canada Canadian Forest Service Northern Forestry Centre 5320 - 122 Street Edmonton, Alberta T6H 3S5 A microfiche edition of this publication may be purchased from: Micromedia Ltd. Suite 305 240 Catherine Street Ottawa, Ontario K2P 2G8 Page ii Aboriginal Entrepreneurship in Forestry Conforence,Ja nuary27-29, 1998 Contents Foreword ......................................... ...........................v Joe De Franceschi, Conference Coordinator, Canadian Forest Service, Alberta Pre-conference Workshop: Where Does My Proiect Fit? Aboriginal Entrepreneurship in Forestry Bruce We ndel, Business Development Bank of Canada, Alberta ...............................2 CESO Celebrates Thirty Years of Service to the Wo rld George F. Ferrand, Regional Manager, Albertaand Western Arctic, CESO, Alberta .................4 Aid from Peace Hills Tr ust Harold Baram, Peace Hills Trust, Alberta ................................................8 Aboriginal Business Canada Lloyd Bisson, Aboriginal Business Canada, Alberta .........................................9 Session 1. The First Nation Forestry -

The Birds of Western Manitoba. [J^'Y

9 20 Seton on the Birds of Western Manitoba. [J^'y April 3, and was abundant until the first of April. A single individual, 22, iSSs- 107. Philohela minor. —A few during March, 1885. *io8. Gallinago delicata. —Not seen in 1884. First seen March 6, 18S5, and last seen April 7. Abundant. *i09. Tetanus solitarius. —A few in April, 1S84, and April, 1S85. no. Actitis macularius.—First seen April, 17, 1SS4, and April 15, 1SS5. Not common. 111. Fulica americana. —One found dead. April 23, 18S4. 112. Branta canadensis. —-One flock, March 3, 1SS5. 113. Anas discors. —Common in April, 1885. 114. Aix sponsa. — One pair, April 4, 1SS5. THE BIRDS OF WESTERN MANITOBA. BY ERNE.ST E. T. SETON. ( Concluded from p. 156.) 130. Trochilus colubris. Ruby-throated Hummingbird. —Not ob- served by me in any part of the Assiniboine Valley, though given a.^ "occasional at Qii'Appelle" ; "specimens seen on Red Deer River, August 16, 1881," and tolerably common along the Red Ri\er. 131. Milvulus forficatus. Scissor-tailed Flycatcher. —Accidental. One found bv Mr. C. W. Nash at Portage la Prairie. October, 1SS4. (See Auk, April, 1S85, p. 2iS.)' 132. Tyrannus tyrannus. Kingbird.—Very abundant summer resi- dent all over. Very common throughout the Winnipegoosis region. Ar- rives May 24; departs August 30. 133. Myiarchus crinitus. Crested Flycatcher. —Very rare summer resident about Winnipeg. Not taken in Assiniboine region, though I believe I have several times heard it near the Big Plain. Taken by Pro- fessor Macoun at Lake Manitoba, June 17, 18S1. 134. Sayornis phcebe. Phcebe. -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

CSD Code Census Subdivision (CSD) Name 2011 Income Score

2011 Income 2011 Education 2011 Housing 2011 Labour Force 2011 CWB 2011 Global Non‐ Type of 2011 NHS CSD Code Census subdivision (CSD) name Score Score Score Activity Score Score Response Province Collectivity Population 1001105 Portugal Cove South 67 36% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 160 1001113 Trepassey 90 42 95 71 74 35% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 545 1001131 Renews‐Cappahayden 78 46 95 82 75 35% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 310 1001144 Aquaforte 72 31% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 90 1001149 Ferryland 78 53 94 70 74 48% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 465 1001169 St. Vincent's‐St. Stephen's‐Peter's River 81 54 94 69 74 37% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 315 1001174 Gaskiers‐Point La Haye 71 39% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 235 1001186 Admirals Beach 79 22% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 85 1001192 St. Joseph's 72 27% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 125 1001203 Division No. 1, Subd. X 76 44 91 77 72 45% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 495 1001228 St. Bride's 76 38 96 78 72 24% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 295 1001281 Chance Cove 74 40% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 120 1001289 Chapel Arm 79 47 92 78 74 38% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 405 1001304 Division No. 1, Subd. E 80 48 96 78 76 20% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 2990 1001308 Whiteway 80 50 93 82 76 25% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 255 1001321 Division No. 1, Subd. F 74 41 98 70 71 45% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 550 1001328 New Perlican 66 28% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 120 1001332 Winterton 78 38 95 61 68 41% Newfoundland and Labrador Non‐Aboriginal 475 1001339 Division No. -

Sask Gazette, Part II, Feb 28, 1997

THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, FEBRUARY 28, 1997 PART II THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, FEBRUARY 28, 1997 REVISED REGULATIONS OF SASKATCHEWAN ERRATA NOTICE Pursuant to the authority given to me by section 12 of The Regulations Act, 1989, The Vital Statistics Regulations, as published in Part II of the Gazette on December 20, 1996, are corrected in the Appendix by striking out the first page of Form V.S.3, as printed on page 1115, and substituting the following: “ Form V.S. 3 Formulaire V.S. 3 [Subsection 10(1)] [Paragraphe 10(1)] Registration of Stillbirth Enregistrement de Mortinaissance ”. Dated at Regina, February 17, 1997. Lois Thacyk, Registrar of Regulations. 39 THE SASKATCHEWAN GAZETTE, FEBRUARY 28, 1997 ERRATA NOTICE Pursuant to the authority given to me by section 12 of The Regulations Act, 1989, The Urban Municipality Amendment Regulations, 1996, being Saskatchewan Regulations 99/96, as published in Part II of the Gazette on December 27, 1996, are corrected in subsection 7(2) by striking out FORM E.4 and FORM E.5 and substituting the following: “FORM E.4 Declaration of Appointed Officials [Section 7.4] I, __________________________, having been appointed to the office(s) of ____________ in the _____________________________________ of _________________________________ DO SOLEMNLY PROMISE AND DECLARE: 1. That I will truly, faithfully and impartially, to the best of my knowledge and ability, perform the duties of the said office(s); 2. That I have not received and will not receive any payment or reward, or promise of payment or reward, for the exercise of any corrupt practice or other undue execution of the said office(s); 3. -

National Assessment of First Nations Water and Wastewater Systems

National Assessment of First Nations Water and Wastewater Systems Saskatchewan Regional Roll-Up Report FINAL Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development January 2011 Neegan Burnside Ltd. 15 Townline Orangeville, Ontario L9W 3R4 1-800-595-9149 www.neeganburnside.com National Assessment of First Nations Water and Wastewater Systems Saskatchewan Regional Roll-Up Report Final Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada Prepared By: Neegan Burnside Ltd. 15 Townline Orangeville ON L9W 3R4 Prepared for: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada January 2011 File No: FGY163080.4 The material in this report reflects best judgement in light of the information available at the time of preparation. Any use which a third party makes of this report, or any reliance on or decisions made based on it, are the responsibilities of such third parties. Neegan Burnside Ltd. accepts no responsibility for damages, if any, suffered by any third party as a result of decisions made or actions based on this report. Statement of Qualifications and Limitations for Regional Roll-Up Reports This regional roll-up report has been prepared by Neegan Burnside Ltd. and a team of sub- consultants (Consultant) for the benefit of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada (Client). Regional summary reports have been prepared for the 8 regions, to facilitate planning and budgeting on both a regional and national level to address water and wastewater system deficiencies and needs. The material contained in this Regional Roll-Up report is: preliminary in nature, to allow for high level budgetary and risk planning to be completed by the Client on a national level. -

2013 Major Projects Inventory

2013 MAJOR PROJECTS INVENTORY The Inventory of Major Projects in Saskatchewan is produced by the Ministry Sector No. of Projects Total Value in $ Millions of the Economy to provide marketing information for Saskatchewan companies from the design and construction phase of the project through the Agriculture 7 342.0 operation and maintenance phases. This inventory lists major projects in Commercial and Retail 78 2,209.5 Saskatchewan, valued at $2 million or greater, that are in planning, design, or Industrial/Manufacturing 6 3,203.0 construction phases. While every effort has been made to obtain the most Infrastructure 76 2,587.7 recent information, it should be noted that projects are constantly being re- Institutional: Education 64 996.3 evaluated by industry. Although the inventory attempts to be as Institutional: Health 23 610.9 comprehensive as possible, some information may not be available at the time Institutional: Non-Health/Education 48 736.5 of printing, or not published due to reasons of confidentiality. This inventory Mining 15 32,583.0 does not break down projects expenditures by any given year. The value of a Oil/Gas and Pipeline 20 5,168.6 project is the total of expenditures expected over all phases of project Power 85 2,191.6 construction, which may span several years. The values of projects listed in Recreation and Tourism 19 757.7 the inventory are estimated values only. Project Phases: Phase 1 - Residential 37 1,742.5 Proposed; Phase 2 - Planning and Design; Phase 3 - Tender and Construction Telecommunications 7 215.7 Total 485 53,345.0 Value in $ Start End Company Project Location Millions Year Year Phase Remarks AGRICULTURE Namaka Farms Inc. -

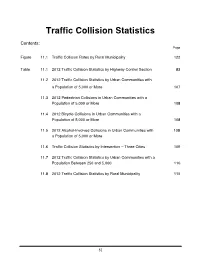

Traffic Collision Statistics

Traffic Collision Statistics Contents: Page Figure 11.1 Traffic Collision Rates by Rural Municipality 122 Table 11.1 2012 Traffic Collision Statistics by Highway Control Section 83 11.2 2012 Traffic Collision Statistics by Urban Communities with a Population of 5,000 or More 107 11.3 2012 Pedestrian Collisions in Urban Communities with a Population of 5,000 or More 108 11.4 2012 Bicycle Collisions in Urban Communities with a Population of 5,000 or More 108 11.5 2012 Alcohol-Involved Collisions in Urban Communities with 108 a Population of 5,000 or More 11.6 Traffic Collision Statistics by Intersection – Three Cities 109 11.7 2012 Traffic Collision Statistics by Urban Communities with a Population Between 250 and 5,000 110 11.8 2012 Traffic Collision Statistics by Rural Municipality 115 81 Traffic Collision Statistics Table 11.1 is a detailed summary of all provincial highways in the province. The length of each section of highway, along with the average daily traffic on that section, is used to calculate travel (kilometres in millions) and a collision rate (collisions per million vehicle kilometres) for each section. Tables 11.2 and 11.3 summarize collisions by community, and Table 11.8 shows a similar summary by rural municipality. Collision rates are calculated based on populations, as well as travel, where applicable. 2012 Quick Facts: • The collision rate for all provincial highways is 0.74 collisions per million vehicle kilometres (Mvkm). • The average number of collisions per 100 people for communities with a population: - of 5,000 or more is 2.80 - of 250 to 4,999 is 0.75 - under 250 is 0.98 • Regina and Saskatoon combined account for 41% of the province’s population and 48% of the collisions. -

Targeted Residential Fire Risk Reduction a Summary of At-Risk Aboriginal Areas in Canada

Targeted Residential Fire Risk Reduction A Summary of At-Risk Aboriginal Areas in Canada Len Garis, Sarah Hughan, Paul Maxim, and Alex Tyakoff October 2016 Executive Summary Despite the steady reduction in rates of fire that have been witnessed in Canada in recent years, ongoing research has demonstrated that there continue to be striking inequalities in the way in which fire risk is distributed through society. It is well-established that residential dwelling fires are not distributed evenly through society, but that certain sectors in Canada experience disproportionate numbers of incidents. Oftentimes, it is the most vulnerable segments of society who face the greatest risk of fire and can least afford the personal and property damage it incurs. Fire risks are accentuated when property owners or occupiers fail to install and maintain fire and life safety devices such smoke alarms and carbon monoxide detectors in their homes. These life saving devices are proven to be highly effective, inexpensive to obtain and, in most cases, Canadian fire services will install them for free. A key component of driving down residential fire rates in Canadian cities, towns, hamlets and villages is the identification of communities where fire risk is greatest. Using the internationally recognized Home Safe methodology described in this study, the following Aboriginal and Non- Aboriginal communities in provinces and territories across Canada are determined to be at heightened risk of residential fire. These communities would benefit from a targeted smoke alarm give-away program and public education campaign to reduce the risk of residential fires and ensure the safety and well-being of all Canadian citizens.