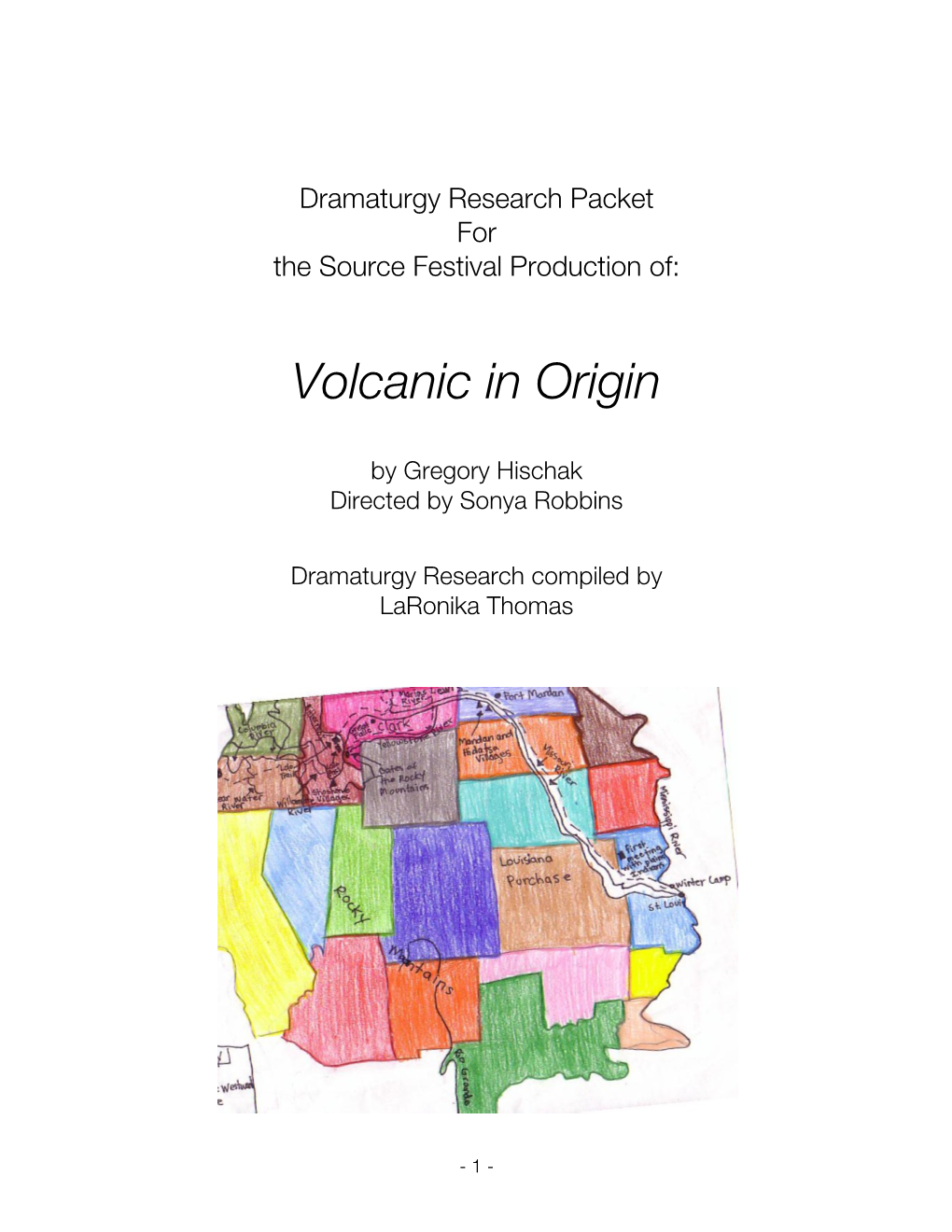

Dramaturgy Research Packet for Volcanic in Origin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second International Interactive Symposium on Ultra-High Performance Concrete UHPC Bridge Deck Overlay in Sioux County, Iowa Ph

Second International Interactive Symposium on Ultra-High Performance Concrete UHPC Bridge Deck Overlay in Sioux County, Iowa Philipp Hadl, Ph.D.* (corresponding author) – UHPC Solutions, 433 Broadway – Suite 604, New York, 10013 NY, USA, (212) 691-4537, Email: [email protected] Marco Maurer – WALO International AG, Heimstrasse 1, 8953 Dietikon, Switzerland, +41 +41 31 941 21 21 228, Email: [email protected] Gregory Nault – LafargeHolcim, 8700 W Bryn Mawr Ave, Ste 300, Chicago, IL 60631, 773- 230-3069, Email: [email protected] Gilbert Brindley –UHPC Solutions, 433 Broadway – Suite 604, New York, 10013 NY, USA (844) 857 8472, Email: [email protected] Ahmad Abu-Hawash – Iowa Department of Transportation, 800 Lincoln Way, Ames, IA 50010, 515-239-1393, Email: [email protected] Dean Bierwagen – Iowa Department of Transportation, 4611 U.S. 75 N, Sioux City, IA 51108, 712-239-1367, Email: [email protected] Curtis Carter – Iowa Department of Transportation, 4611 U.S. 75 N, Sioux City, IA 51108, 712-239-1367, Email: [email protected] Darwin Bishop – Iowa Department of Transportation, 2800 Gordon Dr., P.O. Box 987, Sioux City, IA 51102, 712-274-5826 , Email: [email protected] Dean Herbst – Iowa Department of Transportation, 4611 U.S. 75 N, Sioux City, IA 51108, 712- 239-1367, Email: [email protected] Sri Sritharan, Ph.D.–Professor, Iowa State University, 2711 S Loop Drive, Ames, Iowa 50010, Email : [email protected] Primary Topic Area: Application/Projects Secondary Topic Area: Bridges Date Submitted: (10/17/2018) Abstract Ultra High Performance Concrete (UHPC) on bridges in the United States have typically been joint applications with limited deck overlay placements. -

WPLI Resolution

Matters from Staff Agenda Item # 17 Board of County Commissioners ‐ Staff Report Meeting Date: 11/13/2018 Presenter: Alyssa Watkins Submitting Dept: Administration Subject: Consideration of Approval of WPLI Resolution Statement / Purpose: Consideration of a resolution proclaiming conservation principles for US Forest Service Lands in Teton County as a final recommendation of the Wyoming Public Lands Initiative (WPLI) process. Background / Description (Pros & Cons): In 2015, the Wyoming County Commissioners Association (WCCA) established the Wyoming Public Lands Initiative (WPLI) to develop a proposed management recommendation for the Wilderness Study Areas (WSAs) in Wyoming, and where possible, pursue other public land management issues and opportunities affecting Wyoming’s landscape. In 2016, Teton County elected to participate in the WPLI process and appointed a 21‐person Advisory Committee to consider the Shoal Creek and Palisades WSAs. Committee meetings were facilitated by the Ruckelshaus Institute (a division of the University of Wyoming’s Haub School of Environment and Natural Resources). Ultimately the Committee submitted a number of proposals, at varying times, to the BCC for consideration. Although none of the formal proposals submitted by the Teton County WPLI Committee were advanced by the Board of County Commissioners, the Board did formally move to recognize the common ground established in each of the Committee’s original three proposals as presented on August 20, 2018. The related motion stated that the Board chose to recognize as a resolution or as part of its WPLI recommendation, that all members of the WPLI advisory committee unanimously agree that within the Teton County public lands, protection of wildlife is a priority and that there would be no new roads, no new timber harvest except where necessary to support healthy forest initiatives, no new mineral extraction excepting gravel, no oil and gas exploration or development. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Frontier Fighters and the Romance of the Ranchos By, Jim Stebinger Mr

Newsletter of the Jedediah Smith Society • University of the Pacific, Stockton, California SUMMER 2020 Jedediah Smith in Popular Culture: Frontier Fighters and The Romance of The Ranchos By, Jim Stebinger Mr. Stebinger is a freelance writer, journalist and amateur historian living in Los Angeles. As a UCLA graduate he has had a lifelong interest in history with a focus on western expansion, Jedediah Smith and the mountain fur trade. One of the great surprises of the internet is the extent to up the Missouri. which people will work, research, publish and upload The men go huge amounts of material without recompense. Of course to Ashley’s Wikipedia is the prime example but of perhaps more “mansion” to immediate interest to members of the Society has been the enlist. uploading of vast amounts of “Classic Radio” including at On May 20, least two radio biographies of Jedediah Smith. 1823 we hear raging battle The first piece, which runs 15 minutes 10 seconds, was the “near the present sixth episode of a 39 part series called “Frontier Fighters” 1 boundary of that briefly depicted the lives of men (and some women) North and central to the westward expansion of the United States. South Dakota” Frontier Fighters dramatized soldiers, explorers, mountain Between the men, bankers, doctors and some famous battles including Ashley party the fall of the Alamo. The subjects chosen lived or the events and an enemy occurred from before the founding of the United States up identified as “Arickarees.” Smith is tending to the wounded to about 1900. Although the series is easily available for when Ashley calls for a volunteer to seek aid from Andrew download little is known of the production and crew. -

Dear Supervisors- Attached Please Find Our Letter of Opposition to the SCA Ordinance for Sleepy Hollow As Drafted by Our Attorne

From: Andrea Taber To: Rice, Katie; Kinsey, Steven; Adams, Susan; Arnold, Judy; Sears, Kathrin Cc: Dan Stein; Thorsen, Suzanne; Lai, Thomas Subject: Sleepy Hollow Homeowners Association Letter of Oppostion to the SCA Ordinance Date: Wednesday, May 22, 2013 8:12:53 PM Attachments: Document4.docx Dear Supervisors- Attached please find our letter of opposition to the SCA Ordinance for Sleepy Hollow as drafted by our attorney Neil Moran of Freitas McCarthy MacMahon & Keating, LLP. Sleepy Hollow Homeowners Association May 3, 2013 Board of Supervisors of Marin County 3501 Civil Center Drive San Rafael, CA 94903-4157 Re: Stream Conservation Area (SCA) Proposed Amendments to the Development Code Honorable Members of the Board of Supervisors: INTRODUCTION The Sleepy Hollow Homes Association (SHHA) objects to the proposed changes to Chapters 22.33 (Stream Protection) and 22.63 (Stream Conservation Area Permit) as they would apply to the residents of the unincorporated portion of San Anselmo known as Sleepy Hollow. We ask that the County exempt and/or delay implementation of any changes to Chapters 22.33 and 22.63 as to the city-centered corridor streams, including Sleepy Hollow. The SHHA supports implementation of the proposed amendments to the San Geronimo Valley, to protect wildlife habitat in streams where Coho Salmon currently exist. The SHHA supports regulations to ensure the health and survival of the species in these areas. The SHHA recognizes the urgency of this matter to the San Geronimo Valley, both for the survival of the endangered and declining Coho population and for the property rights of the affected residents who are currently subject to a building moratorium. -

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

2014 - Issue 3 When You’Re on the Job, It’S Important to Have the Right Tools

2014 - ISSUE 3 WHEN YOU’RE ON THE JOB, IT’S IMPORTANT TO HAVE THE RIGHT TOOLS. Anchor Checking. ■ Free worldwide ATMs* ■ Free iPhone® and Android® apps Only from ■ Free online banking, mobile ■ Free domestic incoming wires and Camden National Bank. banking and bill pay cashier’s checks — and more! Wherever you are in the world, you can count on Camden National Bank every step of the way. Visit one of our 44 branches statewide or online at CamdenNational.com to open your account today. *Unlimited refunds when using a non-Camden National Bank ATM in the United States per withdrawal. Accept the disclosure fee and we will refund the surcharge. For ATM transactions outside the United States, Puerto Rico, or U.S. Virgin Islands, we will refund the ATM fee if you bring in the ATM receipt showing the surcharge within 90 days of the transaction. CNBRB_MMAAnchorCheckingAd_PRINT_110714.indd 1 11/7/14 3:10 PM Content MARINER STAFF IN THIS ISSUE Director of College Relations Jennifer DeJoy / [email protected] 26 Editor Laurie Stone / [email protected] Designer & Production Editor Deanna Yocom / [email protected] Ad Representative Deanna Yocom / [email protected] AdministratiON President Dr. William J. Brennan Provost & V. P. for Academic Affairs Meet Emily Wyman ’17. Photo by D Sinclair. Dr. David M. Gardner V. P. for Enrollment Management Dr. Elizabeth True FEatURES V.P. for Operations Dr. Darrell W. Donahue 8 Money:Top Rankings Chief Financial Officer 18 Above & Beyond James Soucie WHEN YOU’RE ON THE JOB, IT’S IMPORTANT TO HAVE THE RIGHT TOOLS. -

The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am

American Indian Law Review Volume 35 | Number 1 1-1-2010 Values in Transition: The hirC icahua Apache from 1886-1914 John W. Ragsdale Jr. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Indigenous Studies Commons, Other History Commons, Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation John W. Ragsdale Jr., Values in Transition: The Chiricahua Apache from 1886-1914, 35 Am. Indian L. Rev. (2010), https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol35/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Oklahoma College of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VALUES IN TRANSITION: THE CHIRICAHUA APACHE FROM 1886-1914 John W Ragsdale, Jr.* Abstract Law confirms but seldom determines the course of a society. Values and beliefs, instead, are the true polestars, incrementally implemented by the laws, customs, and policies. The Chiricahua Apache, a tribal society of hunters, gatherers, and raiders in the mountains and deserts of the Southwest, were squeezed between the growing populations and economies of the United States and Mexico. Raiding brought response, reprisal, and ultimately confinement at the loathsome San Carlos Reservation. Though most Chiricahua submitted to the beginnings of assimilation, a number of the hardiest and least malleable did not. Periodic breakouts, wild raids through New Mexico and Arizona, and a labyrinthian, nearly impenetrable sanctuary in the Sierra Madre led the United States to an extraordinary and unprincipled overreaction. -

NORMAN K Denzin Sacagawea's Nickname1, Or the Sacagawea

NORMAN K DENZIN Sacagawea’s Nickname1, or The Sacagawea Problem The tropical emotion that has created a legendary Sacajawea awaits study...Few others have had so much sentimental fantasy expended on them. A good many men who have written about her...have obviously fallen in love with her. Almost every woman who has written about her has become Sacajawea in her inner reverie (DeVoto, 195, p. 618; see also Waldo, 1978, p. xii). Anyway, what it all comes down to is this: the story of Sacagawea...can be told a lot of different ways (Allen, 1984, p. 4). Many millions of Native American women have lived and died...and yet, until quite recently, only two – Pocahantas and Sacagawea – have left even faint tracings of their personalities on history (McMurtry, 001, p. 155). PROLOGUE 1 THE CAMERA EYE (1) 2: Introduction: Voice 1: Narrator-as-Dramatist This essay3 is a co-performance text, a four-act play – with act one and four presented here – that builds on and extends the performance texts presented in Denzin (004, 005).4 “Sacagawea’s Nickname, or the Sacagawea Problem” enacts a critical cultural politics concerning Native American women and their presence in the Lewis and Clark Journals. It is another telling of how critical race theory and critical pedagogy meet popular history. The revisionist history at hand is the history of Sacagawea and the representation of Native American women in two cultural and symbolic landscapes: the expedition journals, and Montana’s most famous novel, A B Guthrie, Jr.’s mid-century novel (1947), Big Sky (Blew, 1988, p. -

NOTICE of MEETING of the CITY COUNCIL of the CITY of SIOUX CITY, IOWA City Council Agendas Are Also Available on the Internet At

NOTICE OF MEETING OF THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF SIOUX CITY, IOWA City Council agendas are also available on the Internet at www.sioux-city.org. You are hereby notified a meeting of the City Council of the City of Sioux City, Iowa, will be held Monday, December 3, 2018, 4:00 p.m., local time, in the Council Chambers, 5th Floor, City Hall, 405 6th Street, Sioux City, Iowa, for the purpose of taking official action on the agenda items shown hereinafter and for such other business that may properly come before the Council. This is a formal meeting during which the Council may take official action on various items of business. If you wish to speak on an item, please follow the seven participation guidelines adopted by the Council for speakers: 1. Anyone may address the Council on any agenda item. 2. Speakers should approach the microphone one at a time and be recognized by the Mayor. 3. Speakers should give their name, spell their name, give their address, and then their statement. 4. Everyone should have an opportunity to speak. Therefore, please limit your remarks to three minutes on any one item. 5. At the beginning of the discussion on any item, the Mayor may request statements in favor of an action be heard first followed by statements in opposition to the action. 6. Any concerns or questions you may have which do not relate directly to a scheduled item on the agenda will also be heard under ‘Citizen Concerns’. 7. For the benefit of all in attendance, please turn off all cellular phones and other communi- cation devices while in the City Council Chambers. -

Spring/Summer 2020 Newsletter

Spring/Summer 2020 • Vol. 2, Issue 19 Director’s Report by Steve Hansen hese are extraordinary the closure of our facilities lost their lives or their liveli- times! Each generation for three-plus months. As the hood are at the forefront of Twitnesses historic mile- Director, it truly pains me that the suffering and it will take stones and these events we were not able to perform months, and possibly years, shape our lives and those our “normal operations” and for many to recover from who follow us. The year 2020 as a result, at least 15 – 20 their individual and family will be written as one of thousand people who would loss. On behalf of the Muse- the more remarkable ones have normally visited the um family, I offer our support, we have seen in decades. Museum sites were unable to our empathy and I pray for The pandemic with over do so. better times. 100,000 U.S. deaths as of this writing, record As our Museum sites re- unemployment, gov- Thank you for your open, we will do so with ernment-ordered shut- continued support; a deep sigh of relief and downs and nationwide with an obligation to our civil unrest all in the first I have faith in our country, community to fulfill our six months! our community and, mission. We have missed serving the public and While there will be most of all, in our citizens. genuinely look forward many versions of this to welcoming everyone history written, the I realize that in the grand back for a visit. -

Lewis and Clark: the Unheard Voices

Curriculum Connections A free online publication for K-12 educators provided by ADL’s A World of Difference® Institute. www.adl.org/lesson-plans © 1993 by George Littlechild UPDATED 2019 Lewis and Clark: The Unheard Voices CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS | UPDATED FALL 2019 2 In This Issue The disadvantage of [people] not knowing the past is that they do Contents not know the present. History is a hill or high point of vantage, from which alone [they] see the town in which they live or the age Alignment of Lessons to Common —G. K. Chesterson, author (1874–1936) in which they are living. Core Anchor Standards Each year classrooms across the U.S. study, re-enact, and celebrate the Lewis and Clark expedition, a journey that has become an emblematic symbol of Lessons American fortitude and courage. While there are many aspects of the “Corps of Elementary School Lesson Discovery” worthy of commemoration—the triumph over geographical obstacles, the appreciation and cataloging of nature, and the epic proportions Middle School Lesson of the journey—this is only part of the history. High School Lesson While Lewis and Clark regarded the West as territory “on which the foot of civilized man had never trodden,” this land had been home for centuries to Resources millions of Native Americans from over 170 nations. For the descendants of Tribal Nations Whose Homeland these people, celebrations of the Corps of Discovery mark the onset of an era Lewis and Clark Explored of brutal repression, genocide and the destruction of their culture. Resources for Educators and Students The lesson plans in this issue of Curriculum Connections take an in-depth look at the history of U.S.