Petitioner, V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

363 Part 238—Contracts With

Immigration and Naturalization Service, Justice § 238.3 (2) The country where the alien was mented on Form I±420. The contracts born; with transportation lines referred to in (3) The country where the alien has a section 238(c) of the Act shall be made residence; or by the Commissioner on behalf of the (4) Any country willing to accept the government and shall be documented alien. on Form I±426. The contracts with (c) Contiguous territory and adjacent transportation lines desiring their pas- islands. Any alien ordered excluded who sengers to be preinspected at places boarded an aircraft or vessel in foreign outside the United States shall be contiguous territory or in any adjacent made by the Commissioner on behalf of island shall be deported to such foreign the government and shall be docu- contiguous territory or adjacent island mented on Form I±425; except that con- if the alien is a native, citizen, subject, tracts for irregularly operated charter or national of such foreign contiguous flights may be entered into by the Ex- territory or adjacent island, or if the ecutive Associate Commissioner for alien has a residence in such foreign Operations or an Immigration Officer contiguous territory or adjacent is- designated by the Executive Associate land. Otherwise, the alien shall be de- Commissioner for Operations and hav- ported, in the first instance, to the ing jurisdiction over the location country in which is located the port at where the inspection will take place. which the alien embarked for such for- [57 FR 59907, Dec. 17, 1992] eign contiguous territory or adjacent island. -

U.S. Department of Transportation Federal

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ORDER TRANSPORTATION JO 7340.2E FEDERAL AVIATION Effective Date: ADMINISTRATION July 24, 2014 Air Traffic Organization Policy Subject: Contractions Includes Change 1 dated 11/13/14 https://www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/atpubs/CNT/3-3.HTM A 3- Company Country Telephony Ltr AAA AVICON AVIATION CONSULTANTS & AGENTS PAKISTAN AAB ABELAG AVIATION BELGIUM ABG AAC ARMY AIR CORPS UNITED KINGDOM ARMYAIR AAD MANN AIR LTD (T/A AMBASSADOR) UNITED KINGDOM AMBASSADOR AAE EXPRESS AIR, INC. (PHOENIX, AZ) UNITED STATES ARIZONA AAF AIGLE AZUR FRANCE AIGLE AZUR AAG ATLANTIC FLIGHT TRAINING LTD. UNITED KINGDOM ATLANTIC AAH AEKO KULA, INC D/B/A ALOHA AIR CARGO (HONOLULU, UNITED STATES ALOHA HI) AAI AIR AURORA, INC. (SUGAR GROVE, IL) UNITED STATES BOREALIS AAJ ALFA AIRLINES CO., LTD SUDAN ALFA SUDAN AAK ALASKA ISLAND AIR, INC. (ANCHORAGE, AK) UNITED STATES ALASKA ISLAND AAL AMERICAN AIRLINES INC. UNITED STATES AMERICAN AAM AIM AIR REPUBLIC OF MOLDOVA AIM AIR AAN AMSTERDAM AIRLINES B.V. NETHERLANDS AMSTEL AAO ADMINISTRACION AERONAUTICA INTERNACIONAL, S.A. MEXICO AEROINTER DE C.V. AAP ARABASCO AIR SERVICES SAUDI ARABIA ARABASCO AAQ ASIA ATLANTIC AIRLINES CO., LTD THAILAND ASIA ATLANTIC AAR ASIANA AIRLINES REPUBLIC OF KOREA ASIANA AAS ASKARI AVIATION (PVT) LTD PAKISTAN AL-AAS AAT AIR CENTRAL ASIA KYRGYZSTAN AAU AEROPA S.R.L. ITALY AAV ASTRO AIR INTERNATIONAL, INC. PHILIPPINES ASTRO-PHIL AAW AFRICAN AIRLINES CORPORATION LIBYA AFRIQIYAH AAX ADVANCE AVIATION CO., LTD THAILAND ADVANCE AVIATION AAY ALLEGIANT AIR, INC. (FRESNO, CA) UNITED STATES ALLEGIANT AAZ AEOLUS AIR LIMITED GAMBIA AEOLUS ABA AERO-BETA GMBH & CO., STUTTGART GERMANY AEROBETA ABB AFRICAN BUSINESS AND TRANSPORTATIONS DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF AFRICAN BUSINESS THE CONGO ABC ABC WORLD AIRWAYS GUIDE ABD AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC ICELAND ATLANTA ABE ABAN AIR IRAN (ISLAMIC REPUBLIC ABAN OF) ABF SCANWINGS OY, FINLAND FINLAND SKYWINGS ABG ABAKAN-AVIA RUSSIAN FEDERATION ABAKAN-AVIA ABH HOKURIKU-KOUKUU CO., LTD JAPAN ABI ALBA-AIR AVIACION, S.L. -

History of the Dane County Regional Airport

History Of The Dane County Regional Airport 1920’s: Madison’s first airport Barnstormer Howard Morey of Chicago, Edgar Quinn and J.J. McMannamy organized the Madison Airways Corporation. Located near highways 12 and 18 on the south shore of Lake Monona, Madison’s first airport was born. In 1927, the Royal Rapid Transit Company (RRTC) purchased the Madison Airways Corporation. The airport was quickly renamed the Royal Airport and the Royal Airways Corporation (RAC). RRTC provided Madison with the first cabin airplane (which sat five passengers) and the first airline to provide daily service to Chicago. In 1927, the City of Madison purchased 290 acres of land for $35,380. Previously a cabbage patch for a nearby sauerkraut factory, the newly acquired land would later become the present day home of the Dane County Regional Airport. In 1928, RRTC discontinued service to Chicago and liquidated its assets. 1930’s: Madison’s first airplane manufacturing plant Madison welcomes the first airplane manufacturing plant – the Corben Sport Plane Company. Corben designed and produced his semi-built “Super Ace” kits, which included converted Fort Model A motors. In 1934, Corben left Madison amid bankruptcy. Wisconsin artist Cal Peters, in 1936, painted a Depression Era mural of his vision of what the Madison Municipal Airport would be. The mural depicted a terminal building along Highway 51, and two crosswind runways. The restored mural is displayed in the Greeter’s lounge in the center of the main terminal. In January of 1936, the city council voted to accept a WPA grant for construction of four runways and an airplane hangar. -

Master Plan Update Appendix F

APPENDIX F – AIRPORT BACKGROUND Introduction The appendix provides a broad background related to the airport with information covered in the following sections: General History Management/Governing Structure Airline/FBO/Major Tenant History Planning History General History Minot The origins of the City of Minot date back to 1887 during the Dakota Territory land boom, when the Great Northern Railroad made its way through the prairie. From its humble beginnings as a small railroad town, Minot experienced phenomenal growth during the early years of the 20th Century. Minot is home to about 46,000 people and is the regional hub of commerce, health care, finance, agribusiness, education, industry, transportation, and tourism in the area for a total of 76,000 people. The economies of the surrounding predominately rural counties are closely intertwined with Minot. Minot earned its nickname as the ‘Magic City’ after the town virtually sprang up overnight in 1886 growing to 5,000 residents in a few months. Minot International Airport (MOT) Minot's first airstrip was developed by the Minot Park District in the late 1920's on a 20 acre tract in the southern portion of present airport property. The dedication of the "Port of Minot" was held on July 23, 1928 to coincide with the "Ford National Reliability Tour", an event typical of the "barnstorming" days. The Park District eventually transferred all airport property acquired over time to the City of Minot in 1943. The original runway had an east-west orientation. Improvements (i.e., grading, apron area, and lighting) were provided by the Works Progress Administration prior to World War II. -

Research Studies Series a History of the Civil Reserve

RESEARCH STUDIES SERIES A HISTORY OF THE CIVIL RESERVE AIR FLEET By Theodore Joseph Crackel Air Force History & Museums Program Washington, D.C., 1998 ii PREFACE This is the second in a series of research studies—historical works that were not published for various reasons. Yet, the material contained therein was deemed to be of enduring value to Air Force members and scholars. These works were minimally edited and printed in a limited edition to reach a small audience that may find them useful. We invite readers to provide feedback to the Air Force History and Museums Program. Dr. Theodore Joseph Crackel, completed this history in 1993, under contract to the Military Airlift Command History Office. Contract management was under the purview of the Center for Air Force History (now the Air Force History Support Office). MAC historian Dr. John Leland researched and wrote Chapter IX, "CRAF in Operation Desert Shield." Rooted in the late 1930s, the CRAF story revolved about two points: the military requirements and the economics of civil air transportation. Subsequently, the CRAF concept crept along for more than fifty years with little to show for the effort, except for a series of agreements and planning documents. The tortured route of defining and redefining of the concept forms the nucleus of the this history. Unremarkable as it appears, the process of coordination with other governmental agencies, the Congress, aviation organizations, and individual airlines was both necessary and unavoidable; there are lessons to be learned from this experience. Although this story appears terribly short on action, it is worth studying to understand how, when, and why the concept failed and finally succeeded. -

July, 2013 in THIS ISSUE President's

IN THIS ISSUE President’s Message Page 3 Articles Page 13-34 About the Cover Page 5 Letters Page 35-45 Local Reports Page 5-13 In Memoriam Page 45-46 2014 Cruise Information Page 22-24 Calendar Page 48 Volume 16 Number 7 (Journal 646) July, 2013 —— OFFICERS —— President Emeritus: The late Captain George Howson President: Phyllis Cleveland ......................................................... 831-622-7747 .................................... [email protected] Vice Pres: Jon Rowbottom ............................................................ 831-595-5275 ....................................... [email protected] Sec/Treas: Leon Scarbrough ......................................................... 707-938-7324 ...................................... [email protected] Membership Tony Passannante ..................................................... 503-658-3860 ................................... [email protected] —— BOARD OF DIRECTORS —— President - Phyllis Cleveland, Vice President - Jon Rowbottom, Secretary Treasurer - Leon Scarbrough Floyd Alfson, Rich Bouska, Sam Cramb, Ron Jersey, Milt Jines, Tony Passannante Walt Ramseur, Bill Smith, Cleve Spring, Larry Wright —— COMMITTEE CHAIRMEN —— Convention Sites. .......................................................... Ron Jersey ............. [email protected] RUPANEWS Manager ............................................. Cleve Spring ......... [email protected] RUPANEWS Editors................................................ Cleve Spring .................. [email protected] -

Sea King Salute P16 41 Air Mail Tim Ripley Looks at the Operational History of the Westland Sea King in UK Military Service

UK SEA KING SALUTE NEWS N N IO IO AT NEWS VI THE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE OF FLIGHT Incorporating A AVIATION UK £4.50 FEBRUARY 2016 www.aviation-news.co.uk Low-cost NORWEGIAN Scandinavian Style AMBITIONS EXCLUSIVE FIREFIGHTING A-7 CORSAIR II BAe 146s & RJ85s LTV’s Bomb Truck Next-gen Airtankers SUKHOI SUPERJET Russia’s Rising Star 01_AN_FEB_16_UK.indd 1 05/01/2016 12:29 CONTENTS p20 FEATURES p11 REGULARS 20 Spain’s Multi-role Boeing 707s 04 Headlines Rodrigo Rodríguez Costa details the career of the Spanish Air Force’s Boeing 707s which have served 06 Civil News the country’s armed forces since the late 1980s. 11 Military News 26 BAe 146 & RJ85 Airtankers In North America and Australia, converted BAe 146 16 Preservation News and RJ85 airliners are being given a new lease of life working as airtankers – Frédéric Marsaly explains. 40 Flight Bag 32 Sea King Salute p16 41 Air Mail Tim Ripley looks at the operational history of the Westland Sea King in UK military service. 68 Airport Movements 42 Sukhoi Superjet – Russia’s 71 Air Base Movements Rising Star Aviation News Assistant Editor James Ronayne 74 Register Review pro les the Russian regional jet with global ambitions. 48 A-7 Corsair II – LTV’s Bomb Truck p74 A veteran of both the Vietnam con ict and the rst Gulf War, the Ling-Temco-Vought A-7 Corsair II packed a punch, as Patrick Boniface describes. 58 Norwegian Ambitions Aviation News Editor Dino Carrara examines the rapid expansion of low-cost carrier Norwegian and its growing long-haul network. -

Retaining U.S. Air Force Pilots When the Civilian Demand for Pilots Is Growing

Retaining U.S. Air Force Pilots When the Civilian Demand for Pilots Is Growing Michael G. Mattock, James Hosek, Beth J. Asch, Rita Karam C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1455 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9431-5 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover image courtesy of U.S. Air National Guard; photo by Maj. Dale Greer. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface The research discussed in this report was conducted for a project entitled “Pilot Retention Pay Under New Laws.” The purpose of the project was to consider how changes in external demand from airline hiring will affect Air Force pilot retention and provide estimates of how modifications to the aviator retention pay (ARP) and aviator pay (AP) programs will influence Air Force pilot retention. -

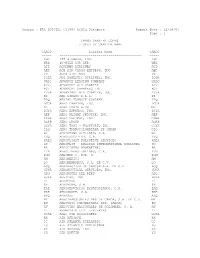

FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1

Source : FAA DOT/TSC CY1997 ACAIS Database Report Date : 12/18/97 Page : 1 CARGO CARRIER CODES LISTED BY CARRIER NAME CARCD Carrier Name CARCD ----- ------------------------------------------ ----- KHC 135 AIRWAYS, INC. KHC WRB 40-MILE AIR LTD. WRB ACD ACADEMY AIRLINES ACD AER ACE AIR CARGO EXPRESS, INC. AER VX ACES AIRLINES VX IQDA ADI DOMESTIC AIRLINES, INC. IQDA UALC ADVANCE LEASING COMPANY UALC ADV ADVANCED AIR CHARTER ADV ACI ADVANCED CHARTERS INT ACI YDVA ADVANTAGE AIR CHARTER, INC. YDVA EI AER LINGUS P.L.C. EI TPQ AERIAL TRANSIT COMPANY TPQ DGCA AERO CHARTER, INC. DGCA ML AERO COSTA RICA ML DJYA AERO EXPRESS, INC. DJYA AEF AERO FLIGHT SERVICE, INC. AEF GSHA AERO FREIGHT, INC. GSHA AGRP AERO GROUP AGRP CGYA AERO TAXI - ROCKFORD, INC. CGYA CLQ AERO TRANSCOLOMBIANA DE CARGA CLQ G3 AEROCHAGO AIRLINES, S.A. G3 EVQ AEROEJECUTIVO, C.A. EVQ XAES AEROFLIGHT EXECUTIVE SERVICES XAES SU AEROFLOT - RUSSIAN INTERNATIONAL AIRLINES SU AR AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS AR LTN AEROLINEAS LATINAS, C.A. LTN ROM AEROMAR C. POR. A. ROM AM AEROMEXICO AM QO AEROMEXPRESS, S.A. DE C.V. QO ACQ AERONAUTICA DE CANCUN S.A. DE C.V. ACQ HUKA AERONAUTICAL SERVICES, INC. HUKA ADQ AERONAVES DEL PERU ADQ HJKA AEROPAK, INC. HJKA PL AEROPERU PL 6P AEROPUMA, S.A. 6P EAE AEROSERVICIOS ECUATORIANOS, C.A. EAE KRE AEROSUCRE, S.A. KRE ASQ AEROSUR ASQ MY AEROTRANSPORTES MAS DE CARGA, S.A. DE C.V. MY ZU AEROVAIS COLOMBIANAS LTD. (ARCA) ZU AV AEROVIAS NACIONALES DE COLOMBIA, S. A. AV ZL AFFRETAIR LTD. (PRIVATE) ZL UCAL AGRO AIR ASSOCIATES UCAL RK AIR AFRIQUE RK CC AIR ATLANTA ICELANDIC CC LU AIR ATLANTIC DOMINICANA LU AX AIR AURORA, INC. -

History of the Dane County Regional Airport

History Of The Dane County Regional Airport 1920’s: Madison’s first airport Barnstormer Howard Morey of Chicago, Edgar Quinn and J.J. McMannamy organized the Madison Airways Corporation. Located near highways 12 and 18 on the south shore of Lake Monona, Madison’s first airport was born. In 1927, the Royal Rapid Transit Company (RRTC) purchased the Madison Airways Corporation. The airport was quickly renamed the Royal Airport and the Royal Airways Corporation (RAC). RRTC provided Madison with the first cabin airplane (which sat five passengers) and the first airline to provide daily service to Chicago. In 1927, the City of Madison purchased 290 acres of land for $35,380. Previously a cabbage patch for a nearby sauerkraut factory, the newly acquired land would later become the present day home of the Dane County Regional Airport. In 1928, RRTC discontinued service to Chicago and liquidated its assets. 1930’s: Madison’s first airplane manufacturing plant Madison welcomes the first airplane manufacturing plant – the Corben Sport Plane Company. Corben designed and produced his semi-built “Super Ace” kits, which included converted Fort Model A motors. In 1934, Corben left Madison amid bankruptcy. Wisconsin artist Cal Peters, in 1936, painted a Depression Era mural of his vision of what the Madison Municipal Airport would be. The mural depicted a terminal building along Highway 51, and two crosswind runways. The restored mural is displayed in the Greeter’s lounge in the center of the main terminal. In January of 1936, the city council voted to accept a WPA grant for construction of four runways and an airplane hangar. -

IATA Airline Designators Air Kilroe Limited T/A Eastern Airways T3 * As Avies U3 Air Koryo JS 120 Aserca Airlines, C.A

Air Italy S.p.A. I9 067 Armenia Airways Aircompany CJSC 6A Air Japan Company Ltd. NQ Arubaanse Luchtvaart Maatschappij N.V Air KBZ Ltd. K7 dba Aruba Airlines AG IATA Airline Designators Air Kilroe Limited t/a Eastern Airways T3 * As Avies U3 Air Koryo JS 120 Aserca Airlines, C.A. - Encode Air Macau Company Limited NX 675 Aserca Airlines R7 Air Madagascar MD 258 Asian Air Company Limited DM Air Malawi Limited QM 167 Asian Wings Airways Limited YJ User / Airline Designator / Numeric Air Malta p.l.c. KM 643 Asiana Airlines Inc. OZ 988 1263343 Alberta Ltd. t/a Enerjet EG * Air Manas Astar Air Cargo ER 423 40-Mile Air, Ltd. Q5 * dba Air Manas ltd. Air Company ZM 887 Astra Airlines A2 * 540 Ghana Ltd. 5G Air Mandalay Ltd. 6T Astral Aviation Ltd. 8V * 485 8165343 Canada Inc. dba Air Canada rouge RV AIR MAURITIUS LTD MK 239 Atlantic Airways, Faroe Islands, P/F RC 767 9 Air Co Ltd AQ 902 Air Mediterranee ML 853 Atlantis European Airways TD 9G Rail Limited 9G * Air Moldova 9U 572 Atlas Air, Inc. 5Y 369 Abacus International Pte. Ltd. 1B Air Namibia SW 186 Atlasjet Airlines Inc. KK 610 ABC Aerolineas S.A. de C.V. 4O * 837 Air New Zealand Limited NZ 086 Auric Air Services Limited UI * ABSA - Aerolinhas Brasileiras S.A. M3 549 Air Niamey A7 Aurigny Air Services Limited GR 924 ABX Air, Inc. GB 832 Air Niugini Pty Limited Austrian Airlines AG dba Austrian OS 257 AccesRail and Partner Railways 9B * dba Air Niugini PX 656 Auto Res S.L.U.