Tier 2 Air Service Study Minnesota in Partnership with Wisconsin 2003

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title: Aviation Collection Reference Code: Mss-1969 Inclusive Dates

Title: Aviation Collection Reference Code: Mss-1969 Inclusive Dates: 1920 – ongoing Quantity: 1.2 cu. ft. total Location: BV 097-098 (0.8 cu. ft.) RC9, Sh. 007 & 015 (0.4 cu. ft.) Scope and Content: This collection contains general aviation documents on the local, state and national level as well as files on more specific subjects such as Hamilton Field and the EAA. In addition, this collection includes pamphlets from various airlines. Access and Use: No restrictions Language: English Notes: The collection was processed by Jeewon Schally, April 1993, and added to multiple times by Steve Daily and Kevin Abing. Arrangement: Folder Heading Box # File # Hamilton Field (1926) 1 1 Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA) (1971-1990) 1 2 Aviators 1 3 - Clara Adams (1939) - Charles A. Lindbergh (1920, 1927-1928) [Includes letter re Lindbergh’s Special Air Mail flight from Milwaukee-Chicago-St. Louis) - Richard Ira Bong - Douglas Corrigan Milwaukee 1 4 - "National Transportation Week" by The Milwaukee Journal (1966) - "On the Move" by The Milwaukee Sentinel (1966) - Badger Jaycee National Air Show Program (1966) - Jaycee Aero Space Exposition (1965) - Post card from Midwest Airways, Inc., depicting the "sister-ship" of Lindbergh's "Spirit of St. Louis," ca. 1927 - Newspaper clipping, "What Could Have Been," on Alfred Lawson, 1991 - "America's First Airliner," by Francis J. Allen, Air Classics, November 1984 - Program/menu honoring Capt. Wolfgang Von Gronau, 1932 - “Milwaukee County’s First Airport” by George Hardie - “Milwaukee’s First Airliner” by George Hardie - Membership Application/Information Card for Aero Club of Wisconsin - Program, Air Force Association Billy Mitchell Award, ca. -

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

SERVICE (Aerospace Corp.', ,E'" Eduna-P AIR Clif.) 100. P HC A05/9

SERVICE(NIASA-cx-152005) (Aerospace ACorp.', STUDY ,E'"OF OMMUIXeduna-P CAIR N7721l Clif.) 100. p HC A05/9; A04. SC 01C Uca G3/03 37064 / A • HEAEROSPACE CORPORATION NASA CR- 152005 A STUDY OF COMMUTER AIR SERVICE By F.W. Belina and L.R. Bush June 1977 f Distribution of this report is provided in the interest of information exchange. Responsibility for the contents resides in the author or organization that prepared it. Prepared under Contract No. NASZ-9380 by THE AEROSPACE CORPORATION El Segundo, California for AMES RESEARCH CENTER NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION REPRODUCED BY NATIONAL TECHNICAL INFORMATION SERVICE U.S. DEPARTMENT OFCOMMERCE SPRINGFIELD, V 22161M A STUDY OF COMMUTER AIR SERVICE Approved by S. Sokoisky, Director H. Bernstein, Group Director, Systems Planning Off e, Transportation Grou Transportation Group ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Appreciation is extended to Mr. Thomas Galloway, NASA Technical Monitor and Mr. Mark Waters, NASA Alternate Technical Monitor for their assistance and guidance during the study. Of special importance, however, were the contributions of Messrs. Tom Miles and Martin Macy of the Commuter Airline Association of America and the key personnel of the following commuter and certificated air carriers: Air Carolina Metro Airlines Air Midwest (Certificated) Midstate Airlines Air New England (Certificated) New England Airlines Air Wisconsin Pilgrim Airlines Alaska Aeronautical Puerto Rico International Airlines Altair Airlines Rio Airways Antilles Air Boats Rocky Mountain Airways Atlantic City Airlines Royal Hawaiian Airways Bar Harbor Airlines Scenic Airlines Cascade Airways Seaplane Shuttle Transport Catalina Airlines SMB Stagelines Cochise Airlines Swift Aire Lines Cumberland Airlines Sky West Aviation Execuair Airlines Suburban Airlines Florida Airlines Tyee Airlines Golden West Airlines Zia Airlines Without their excellent cooperation, this study would not have been possible. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

Palm Beach International Airport (PBI)

Agenda Item:~ PALM BEACH COUNTY BOARD OF COUNTY COMMISSIONERS AGENDA ITEM SUMMARY -===================================================================== Meeting Date: January 12, 2021 [ ] Consent [ X] Regular [ ] Ordinance [ ] Public Hearing Submitted By: Department of Airports ---------------------------------------------------------------------- I. EXECUTIVE BRIEF Motion and Title: Staff recommends motion to approve: a Contract for Air Service Development Consulting Services (Contract) with Ailevon Pacific Aviation Consulting LLC (Ailevon), a Florida limited liability company, commencing on February 1, 2021, and expiring on January 31, 2024, with one 24-month option to renew for an amount not to exceed $200,000 per contract year for a total not to exceed amount of $600,000 for the initial term. Summary: This Contract provides for professional and technical consulting services on an as-needed basis in support of the air service development program for the Palm Beach International Airport (PBI). Ailevon's principal place of business is Atlanta, GA. Air service development consulting services may include, but are not limited to, air service strategy and planning, airline route study and forecasting, competitive service analysis, business case development for new/expanded air service, development of incentive programs, catchment area demographic and leakage studies and analysis of air traffic demand and airfare data. The Contract provides for a not to exceed amount of $200,000 per contract year with an initial three-year term and an option to renew for an additional 24 months at the County's sole option. Due to lack of availability of qualified Small/Minority/Women Owned Business Enterprises providing the services required by this Contract, the Office of Equal Business Opportunity issued a waiver of Affirmative Procurement Initiatives on July 30, 2020. -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

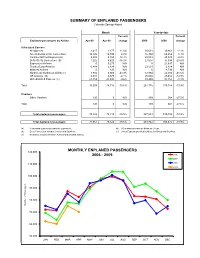

APR 2009 Stats Rpts

SUMMARY OF ENPLANED PASSENGERS Colorado Springs Airport Month Year-to-date Percent Percent Enplaned passengers by Airline Apr-09 Apr-08 change 2009 2008 change Scheduled Carriers Allegiant Air 2,417 2,177 11.0% 10,631 10,861 -2.1% American/American Connection 14,126 14,749 -4.2% 55,394 60,259 -8.1% Continental/Cont Express (a) 5,808 5,165 12.4% 22,544 23,049 -2.2% Delta /Delta Connection (b) 7,222 8,620 -16.2% 27,007 37,838 -28.6% ExpressJet Airlines 0 5,275 N/A 0 21,647 N/A Frontier/Lynx Aviation 6,888 2,874 N/A 23,531 2,874 N/A Midwest Airlines 0 120 N/A 0 4,793 N/A Northwest/ Northwest Airlink (c) 3,882 6,920 -43.9% 12,864 22,030 -41.6% US Airways (d) 6,301 6,570 -4.1% 25,665 29,462 -12.9% United/United Express (e) 23,359 25,845 -9.6% 89,499 97,355 -8.1% Total 70,003 78,315 -10.6% 267,135 310,168 -13.9% Charters Other Charters 120 0 N/A 409 564 -27.5% Total 120 0 N/A 409 564 -27.5% Total enplaned passengers 70,123 78,315 -10.5% 267,544 310,732 -13.9% Total deplaned passengers 71,061 79,522 -10.6% 263,922 306,475 -13.9% (a) Continental Express provided by ExpressJet. (d) US Airways provided by Mesa Air Group. (b) Delta Connection includes Comair and SkyWest . (e) United Express provided by Mesa Air Group and SkyWest. -

Facts & Figures & Figures

OCTOBER 2019 FACTS & FIGURES & FIGURES THE STAR ALLIANCE NETWORK RADAR The Star Alliance network was created in 1997 to better meet the needs of the frequent international traveller. MANAGEMENT INFORMATION Combined Total of the current Star Alliance member airlines: FOR ALLIANCE EXECUTIVES Total revenue: 179.04 BUSD Revenue Passenger 1,739,41 bn Km: Daily departures: More than Annual Passengers: 762,27 m 19,000 Countries served: 195 Number of employees: 431,500 Airports served: Over 1,300 Fleet: 5,013 Lounges: More than 1,000 MEMBER AIRLINES Aegean Airlines is Greece’s largest airline providing at its inception in 1999 until today, full service, premium quality short and medium haul services. In 2013, AEGEAN acquired Olympic Air and through the synergies obtained, network, fleet and passenger numbers expanded fast. The Group welcomed 14m passengers onboard its flights in 2018. The Company has been honored with the Skytrax World Airline award, as the best European regional airline in 2018. This was the 9th time AEGEAN received the relevant award. Among other distinctions, AEGEAN captured the 5th place, in the world's 20 best airlines list (outside the U.S.) in 2018 Readers' Choice Awards survey of Condé Nast Traveler. In June 2018 AEGEAN signed a Purchase Agreement with Airbus, for the order of up to 42 new generation aircraft of the 1 MAY 2019 FACTS & FIGURES A320neo family and plans to place additional orders with lessors for up to 20 new A/C of the A320neo family. For more information please visit www.aegeanair.com. Total revenue: USD 1.10 bn Revenue Passenger Km: 11.92 m Daily departures: 139 Annual Passengers: 7.19 m Countries served: 44 Number of employees: 2,498 Airports served: 134 Joined Star Alliance: June 2010 Fleet size: 49 Aircraft Types: A321 – 200, A320 – 200, A319 – 200 Hub Airport: Athens Airport bases: Thessaloniki, Heraklion, Rhodes, Kalamata, Chania, Larnaka Current as of: 14 MAY 19 Air Canada is Canada's largest domestic and international airline serving nearly 220 airports on six continents. -

The Port of Portland

NEW ISSUE—BOOK ENTRY ONLY RATING: SEE “RATING” In the opinion of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP, Bond Counsel, based upon an analysis of existing laws, regulations, rulings and court decisions and assuming, among other matters, the accuracy of certain representations and compliance with certain covenants, interest on the Series Twenty-Four Bonds is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes under Section 103 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, except that no opinion is expressed as to the status of interest on any Series Twenty-Four B Bond for any period that such Series Twenty-Four B Bond is held by a “substantial user” of the facilities financed or refinanced by the Series Twenty-Four B Bonds or by a “related person” within the meaning Section 147(a) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986. Bond Counsel observes that interest on the Series Twenty-Four B Bonds is a specific preference item for purposes of the federal individual and corporate alternative minimum taxes. In the further opinion of Bond Counsel, interest on the Series Twenty-Four A Bonds is not a specific preference item for purposes of the federal individual and corporate alternative minimum taxes, although Bond Counsel observes that such interest is included in adjusted current earnings when calculating corporate alternative minimum taxable income. Bond Counsel also is of the opinion based upon existing laws of the State of Oregon interest on the Series Twenty-Four Bonds is exempt from personal income taxation by the State of Oregon. Bond Counsel expresses no opinion regarding any other tax consequences related to the ownership or disposition of, or the accrual or receipt of interest on, the Series Twenty-Four Bonds. -

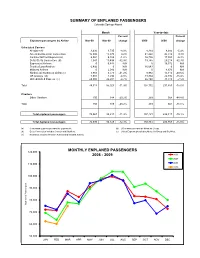

MAR 2009 Stats Rpts

SUMMARY OF ENPLANED PASSENGERS Colorado Springs Airport Month Year-to-date Percent Percent Enplaned passengers by Airline Mar-09 Mar-08 change 2009 2008 change Scheduled Carriers Allegiant Air 3,436 3,735 -8.0% 8,214 8,684 -5.4% American/American Connection 15,900 15,873 0.2% 41,268 45,510 -9.3% Continental/Cont Express (a) 6,084 6,159 -1.2% 16,736 17,884 -6.4% Delta /Delta Connection (b) 7,041 10,498 -32.9% 19,785 29,218 -32.3% ExpressJet Airlines 0 6,444 N/A 0 16,372 N/A Frontier/Lynx Aviation 6,492 0 N/A 16,643 0 N/A Midwest Airlines 0 2,046 N/A 0 4,673 N/A Northwest/ Northwest Airlink (c) 3,983 6,773 -41.2% 8,982 15,110 -40.6% US Airways (d) 7,001 7,294 -4.0% 19,364 22,892 -15.4% United/United Express (e) 24,980 26,201 -4.7% 66,140 71,510 -7.5% Total 74,917 85,023 -11.9% 197,132 231,853 -15.0% Charters Other Charters 150 188 -20.2% 289 564 -48.8% Total 150 188 -20.2% 289 564 -48.8% Total enplaned passengers 75,067 85,211 -11.9% 197,421 232,417 -15.1% Total deplaned passengers 72,030 82,129 -12.3% 192,861 226,953 -15.0% (a) Continental Express provided by ExpressJet. (d) US Airways provided by Mesa Air Group. (b) Delta Connection includes Comair and SkyWest . (e) United Express provided by Mesa Air Group and SkyWest. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums

12 May 2008 CHART #1616 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Forever Don't Hold Back Unbreakable: 2008 NZ Tour Edition 50th Anniversary 1 Chris Brown 21 The Potbelleez 1 Westlife 21 Gray Bartlett Last week 5 / 3 weeks SBME Last week 22 / 12 weeks MOS/Universal Last week 10 / 22 weeks Platinum x1 / SBME Last week 17 / 3 weeks EMI Take A Bow Stop And Stare Rockferry Past, Present, Future 2 Rihanna 22 OneRepublic 2 Duffy 22 Tiki Taane Last week 4 / 2 weeks Universal Last week 18 / 17 weeks Universal Last week 3 / 5 weeks Gold x1 / Universal Last week 22 / 25 weeks Gold x1 / DirtyDub/Rhythm/DRM... Love In This Club Tattoo Flight Of The Conchords Rejoice 3 Usher feat. Young Jeezy 23 Jordin Sparks 3 Flight Of The Conchords 23 Katherine Jenkins Last week 1 / 10 weeks Gold x1 / SBME Last week 36 / 2 weeks SBME Last week 1 / 3 weeks Gold x1 / SubPop/Rhythmethod Last week 32 / 3 weeks Universal No Air Sorry Believe Legend: The Very Best Of 4 Jordin Sparks feat. Chris Brown 24 Buckcherry 4 Geoff Sewell 24 Willie Nelson Last week 2 / 10 weeks Platinum x1 / SBME Last week 26 / 6 weeks Universal Last week 2 / 4 weeks Gold x1 / SewellMusic/Ode Last week 18 / 6 weeks Gold x1 / SBME Lollipop What Is It? Back To Black: Deluxe Edition E=MC2 5 Lil Wayne 25 Baby Bash feat. Sean Kingston 5 Amy Winehouse 25 Mariah Carey Last week 6 / 3 weeks Universal Last week 33 / 6 weeks SBME Last week 6 / 49 weeks Platinum x2 / Universal Last week 20 / 3 weeks Universal 4 Minutes Party People The Swing Sessions Watershed 6 Madonna feat. -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A.