Article.Pdf to the Child Had to Be Shared

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit Exhibition, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia

Review essay HenRy Ossawa TanneR: MOdeRn spiRiT exHibiTiOn, pennsylvania acadeMy Of fine aRTs, pHiladelpHia Alexia I. Hudson he Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) is located in Philadelphia within walking distance of City Hall. Founded in T1805 by painter and scientist Charles Willson Peale, sculptor William Rush, and other artists and business leaders, PAFA holds the distinction of being the oldest art school and art museum in the United States. Its current “historic landmark” build- ing opened in 1876, three years before Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937) enrolled as one of PAFA’s first African American students. Tanner would later become the first African American artist to achieve international acclaim for his work. Today, PAFA is comprised of two adjacent buildings—the “historic landmark” building at 118 North Broad Street and the Samuel M. V. Hamilton Building at 128 N. Broad Street. The oldest building was designed by architects Frank Furness and George W. Hewitt and has been designated a National Historic Landmark, hence its name. In 1976 PAFA underwent a delicately managed restoration process to ensure that the archi- tectural and historical integrity of the building was maintained. pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 79, no. 2, 2012. Copyright © 2012 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Wed, 14 Mar 2018 15:39:34 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAH 79.2_06_Hudson.indd 238 18/04/12 12:28 AM review essays The Lenfest Plaza opened adjacent to PAFA on October 1, 2011, and was celebrated with the inaugural lighting of “Paint Torch,” a sculpture by inter- nationally renowned American artist Claes Oldenburg. -

Beyond the Orientalist Canon: Art and Commerce

© COPYRIGHT by Fanna S. Gebreyesus 2015 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED 1 BEYOND THE ORIENTALIST CANON: ART AND COMMERCE IN JEAN-LÉON GÉRÔME'S THE SNAKE CHARMER BY Fanna S. Gebreyesus ABSTRACT This thesis re-examines Jean-Léon Gérôme's iconic painting The Snake Charmer (1879) in an attempt to move beyond the post-colonial interpretations that have held sway in the literature on the artist since the publication of Linda Nochlin’s influential essay “The Imaginary Orient” in 1989. The painting traditionally is understood as both a product and reflection of nineteenth-century European colonial politics, a view that positions the depicted figures as racially, ethnically and nationally “other” to the “Western” viewers who encountered the work when it was exhibited in France and the United States during the final decades of the nineteenth century. My analysis does not dispute but rather extends and complicates this approach. First, I place the work in the context of the artist's oeuvre, specifically in relation to the initiation of Gérôme’s sculptural practice in 1878. I interpret the figure of the nude snake charmer as a reference to the artist’s virtuoso abilities in both painting and sculpture. Second, I discuss the commercial success that Gérôme achieved through his popular Orientalist works. Rather than simply catering to the market for Orientalist scenes, I argue that this painting makes sophisticated commentary on its relation to that market; the performance depicted in the work functions as an allegory of the painting’s reception. Finally, I discuss the display of this painting at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, in an environment of spectacle that included the famous “Oriental” exhibits in the Midway Plaisance meant to dazzle and shock visitors. -

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74} UNITED STAThS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Henry O« Tanner Homesite AND/OR COMMON Henry O. Tanner Homes!re [LOCATION STREET & NUMBER 2908 W. Diamond Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Philadelphia __. VICINITY OF Second STATE cog COUNTY ' CODE Pennsylvania Philadelpha 101 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _ DISTRICT _ PUBLIC .^OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE _ MUSEUM JSBUILDING(S) ^.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL _ PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ^.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION - N ° —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME _______Mr. Robert Thornton STREET & NUMBER 2908 W. Diamond Street CITY, TOWN STATE Philadelphia VICINITY OF Pennsylvania LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION Book JAH, No. 269 COURTHOUSE, pp.145-147 REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC. Registry of Deeds, City Hall, Room 153 STREET& NUMBER Broad and Market Streets CITY, TOWN STATE Philadelphia Pennsylvania 19107 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None Known DATE — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED .XORIGINALSITE —GOOD RUINS 2S.ALTERED Mnypn HATF J^FAIR _ UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Henry O. Tanner's Homesite is a three-story masonry structure with wood framed bay (front facade) and wood shed (rear facade). Both the bay and cornice have been recently altered and covered with aluminum siding so that their original architectural character is no longer clear. -

The Annunciation

THE ANNUNCIATION We see a teenage girl, dressed in peasant robes, sitting on a rumpled bed in a room with a bumpy, cobblestone floor. She seems afraid and awed. Who could she be? What is happening? What is that bright column of light on the left? This painting is an unusual version of one of the oldest themes in European art, the Annun- 1898 Oil on canvas ciation (which means announcement). In this New Testament Bible 57 x 71 1/4 inches (144.8 x 181 cm) story, the angel Gabriel tells Mary that she will become the mother Framed: 73 3/4 x 87 1/4 inches (187.3 x 221.6 cm) of Jesus. Traditional paintings of the Annunciation show Mary HENRY OSSAWA TANNER wearing fancy blue robes and seated in a European palace or cathe- American (active France) dral, as she listens calmly to an angel with glorious wings and a halo. Purchased with the W. P. Wilstach Fund, 1899, W1899-1-1 Tanner made his painting so different from other artists’ paintings of the same subject because he wanted the scene to be realistic. LET’S LOOK Who is this person? He painted The Annunciation in 1898, just after returning from his first trip to the Holy Land—Egypt and Palestine (now Israel). Sket- How old do you think she is? ching ordinary Jewish people in the settings where Jesus lived What is she wearing? moved Tanner deeply, and he tried to make his painting as How is she sitting? authentic as possible. How is she holding her hands and her body? Tanner’s academic training is evident in his skillful depiction of What expression does Mary’s tense face and body and in his use of thin, transparent coats she have on her face? of paint called glazes to create the dark shadows and the soft, Where is she? luminous effect. -

30.3 Modernism and Realism

Europe and America, 1800-1870, Modernism and Realism • Examine the meanings of “Modernism” and “Realism” and the rejection of Renaissance illusionistic space. • Understand the changes in Realist art in form, style, and content. • Examine the use of art – especially photography and printmaking -- to provide social commentary. 1 The Art of Realism • Understand Realist art in its forms, styles, and content. • Examine the social commentary, shocking subject matter, formal elements, and public reaction to Realism. 2 Realist Influences: Pieter Breughel Louis Le Nain, Family of Country People, ca. 1640 Le Nain Brothers, The Cart or Return from Haymaking, 1641 Realist Influences: Chardin, Woman Cleaning Turnips, 1738 Figure 30-27 GUSTAVE COURBET, The Stone Breakers, 1849. Oil on canvas, 5’ 3” x 8’ 6”. Formerly at Gemäldegalerie, Dresden (destroyed in 1945). 7 Figure 30-28 GUSTAVE COURBET, Burial at Ornans, 1849. Oil on canvas, 10’ 3 1/2” x 22’ 9 1/2”. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. 8 GUSTAVE COURBET, The Painter’s Studio: A Real Allegory of a Seven Year Phase in my Artistic and Moral Life, 1855. Oil on canvas, 11’ 10” x 19’ 9 ”. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. 9 Figure 30-29 JEAN-FRANÇOIS MILLET, The Gleaners, 1857. Oil on canvas, 2’ 9” x 3’ 8”. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. 10 Figure 30-32 ROSA BONHEUR, The Horse Fair, 1853–1855. Oil on canvas, 8’ 1/4” x 16’ 7 1/2”. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (gift of Cornelius Vanderbilt, 1887). 11 ROSA BONHEUR, Plowing in the Nivervais, 1849. Oil on canvas, 5’ 9” x 8’ 8”. -

Henry Ossawa Tanner

The Clerk’s Black History Series Debra DeBerry Clerk of Superior Court DeKalb County Henry Ossawa Tanner (June 21, 1859 – May 25, 1937) “First African-American Artist in the White House Art Collection” Henry Ossawa Tanner was born in Pennsylvania on June 21, 1859. His parents were, Reverend Benjamin Tucker Tanner, a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal Church, and Sarah Tanner, a mulatto woman who escaped her enslavers via the Underground Railroad. His middle name, Ossawa, was derived from the name of the town Osawatomie, Kansas, where the abolitionist John Brown initiated his antislavery campaign. His father often consulted with Frederick Douglas. At the age of 21, Henry entered the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts study- ing under renowned artist, Thomas Eakins. As the only African-American student, he suffered discrimination at the hands of some of his fellow students, being physically assaulted and having his painting supplies damaged. Despite the efforts to limit his talent, Henry was able to exhibit some of his work at the Academy and at the Philadelphia Society of Artists. Henry left the Pennsylvania Academy prior to graduating to pursue the idea of combining business with art. In the fall of 1888, he moved to Atlanta, Georgia, opened a photography studio, and began teaching art classes at Clark (University) College. In 1891, Henry traveled to Paris with the American Art Students’ Club and enrolled in the Académie Julian. His early art showcased his social awareness and talent for painting dignified and sympathetic portrayals of Black people, such as The Banjo Lesson (1893) and The Thankful Poor (1894). -

The Advent of "The Nigger": the Careers of Paul Laurence Dunbar, Henry 0

The Advent of "The Nigger": The Careers of Paul Laurence Dunbar, Henry 0. Tanner, and Charles W. Chesnutt1 Matthew Wilson Pretext: The Chicago World's Columbian Exposition as Racial Locus In 1893, America celebrated itself in the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago2 in the aptly named "White City." Although the term came from the dazzling quality of the architecture surrounding the Court of Honor, the term "white" was inevitably racialized at the end of the nineteenth century. An ex ample of this racialization is a poem by Richard Watson Gilder, the editor of the Atlantic, entitled "The White City." In this paean, he connects the exposition to the world of ancient Greece: "Her white-winged soul sinks on the New World's breast. /Ah! happy West - / Greece flowers anew, and all her temples soar!"3 He constructs a tradition in which the Greeks were "white" and the United States the fruition of that whiteness, a connection reinforced by the pastiche of classi cal allusions in the architecture of the fair. Thus, the White City could be read as emblematic of the triumph of whiteness in a decade that saw the repression of African American political and economic aspirations. Since the end of Reconstruction and the withdrawal of federal troops from the South following the election of 1876, African Americans had been progres sively robbed of their political rights. As Charles Chesnutt himself noted in his essay "The Disfranchisement of the Negro" (1903), "the rights of Negroes are at a lower ebb than at any time during the thirty-five years of their freedom, and the 0026-3079/2002/4301-005$3.50/0 American Studies, 43:1 (Spring 2002): 5-50 5 6 Matthew Wilson race prejudice more intense and uncompromising."4 In addition, the lynchings in Atlanta in 1892 of three African American businessmen and the coup d'état/ pogrom in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1898 (the subject of Chesnutt's The Marrow of Tradition) signaled that African Americans in the South would not be allowed to compete economically with European Americans. -

A Missing Question Mark: the Unknown Henry Ossawa Tanner

Will South A Missing Question Mark: The Unknown Henry Ossawa Tanner Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009) Citation: Will South, “A Missing Question Mark: The Unknown Henry Ossawa Tanner,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009), http://www.19thc- artworldwide.org/autumn09/a-missing-question-mark. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. South: A Missing Question Mark: The Unknown Henry Ossawa Tanner Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 8, no. 2 (Autumn 2009) A Missing Question Mark: The Unknown Henry Ossawa Tanner by Will South Race remains at the heart of Henry Ossawa Tanner studies. Though he would have wished it not to be so, the issue of Tanner's African American identity defined him in the late nineteenth century and continues to be the criterion by which twenty-first-century audiences appraise his legacy. Tanner struggled and sacrificed to become a recognized and accomplished painter of spiritual narratives, while we would have him also be a reluctant hero—the artist who against all odds overcame social barriers to shine at the Paris Salons, see his work purchased by the Musée du Luxembourg, and be compared critically with James McNeill Whistler. Tanner's path to artistic success was indeed marked by instances of insult and injustice, and his career ascendancy was a remarkable feat. He lived his life, however, one that was driven by a commitment to the creation of art, in conflict with the hopeful expectations of many of his contemporaries. -

Masterpiece: the Banjo Lesson, 1893

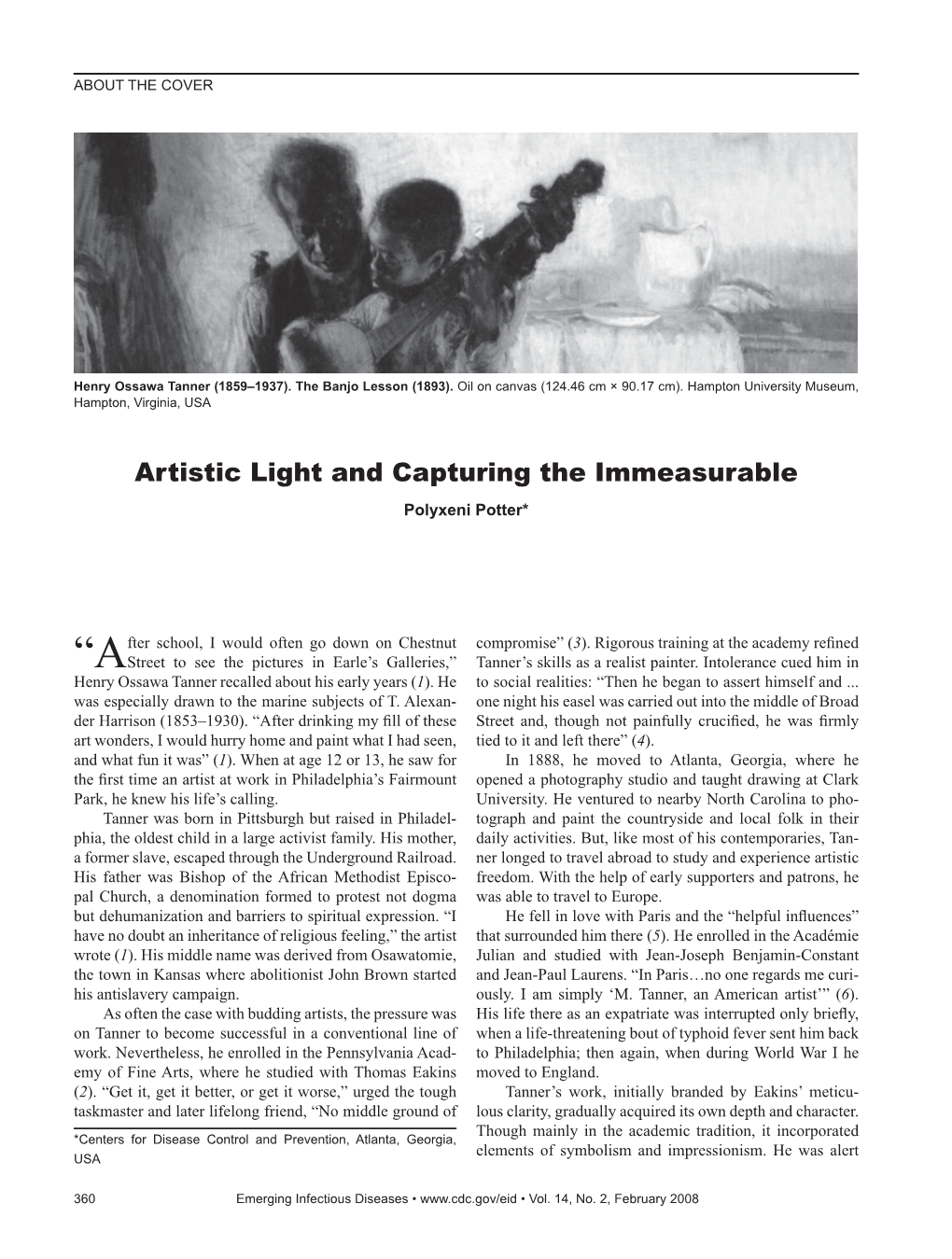

Masterpiece: The Banjo Lesson , 1893 by Henry Ossawa Tanner Keywords: Mood, Light and Composition, Portrait Grade: 3rd Grade Month: February Activity: Family Portraits Meet the Artist: • Henry Ossawa Tanner was born in 1859 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. His father was a minister in the African Methodist Church which influenced his later paintings of religious subjects. • He was an African American artist best known for his paintings of religious subjects, genre scenes and portraits and was the first African American artist to gain international acclaim. • At the age of 21, Tanner enrolled at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia at a time when new methods of drawing the weight and structure of the human figure were developing such as using live models, open discussion of the male and female anatomy and dissections of cadavers to understand the human body. • Although Tanner was extremely successful at the Academy and as an artist, he was not fully accepted in the art world as racism was a prevalent condition in Philadelphia. • In late 1891, Tanner left America for France and except for occasional brief returns home; he would spend the rest of his life there. He died in Paris in 1937. • On one of his short trips home, he painted his most famous work, The Banjo Lesson which depicts an elderly black man teaching what is assumed to be his grandson how to play the banjo. What set this portrait apart from other images of black musicians by other artists of the time is that Tanner skillfully portrays the people as real and not caricatures. -

The Night Escape by HEIDI J

Copyright © 2016 Institute for Faith and Learning at Baylor University Due to copyright restrictions, this image is only available in the print version of Christian Reflection. Henry Ossawa Tanner portrays the holy family’s clandes- tine travel to escape persecution, an event that resonated with the artist’s personal story. Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859-1937), FLIGHT INTO EGYPT (1923). Oil on canvas. 29” x 26”. Marguerite and Frank A. Cosgrove Jr. Fund, 2001. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Image copy- right © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image Source: Art Resource, NY. Used by permission. Copyright © 2016 Institute for Faith and Learning at Baylor University 69 The Night Escape BY HEIDI J. HORNIK he story of the holy family’s night flight into Egypt to escape King Herod’s assassins (Matthew 2:13-18) invites artists to paint a scene Tshrouded in darkness and imbued with moral symbolism. Henry Ossawa Tanner achieves this foreboding mood in Flight into Egypt. It depicts the artist’s favorite biblical story, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, where the painting has been located since 2001.1 Tanner was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where his father, Benja- min Tanner, was a prominent minister. His mother, Sarah Miller, had been a slave before she escaped via the Underground Railway. Tanner became an accomplished illustrator and photographer before concentrating on painting. He studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts from 1880 to 1882 under Thomas Eakins, then moved to Atlanta where he opened a photogra- phy gallery and taught drawing at Clark University for a few years. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

THE ART OF BECOMING: MIMICRY, AMBIVALENCE, AND ORIENTALISM IN THE WORK OF HENRY OSSAWA TANNER AND HILDA RIX By LAURA M. WINN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Laura M. Winn To my first teachers, my Mom and Dad, for giving me the lifelong gift and love for learning ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many people that helped in facilitating and supporting the long and challenging journey of researching and writing this dissertation. I am grateful to all of them. None of this would have been possible without the guidance of my committee members Ashley Jones, Brigitte Weltman-Aron, Elisabeth Fraser, and Nika Elder. Thank you for being so generous with your time, expertise, and thoughtful suggestions. I am especially indebted to my advisor and the chair of the committee, Melissa Hyde, for her willingness to adopt a Classicist interested in gender studies and introduce me to the importance–and fun–of dix-huitième scholarship. Melissa worked through multiple iterations and drafts of this project to clarify and refine my arguments, helping to bring a greater coherence and new voice to the exceptional lives and artistic contributions of Henry Ossawa Tanner and Hilda Rix Nicholas. Through every phase of my graduate education at Florida she has been a vital resource and mentor. I feel incredibility fortunate to have been her student. Crystalizing ideas into a finished dissertation often felt like an insurmountable challenge. I greatly benefited from the support, feedback, and experience of my “girl gang” at Florida. -

Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (Exhibition)

Theresa Leininger-Miller exhibition review of Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (exhibition) Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013) Citation: Theresa Leininger-Miller, exhibition review of “Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (exhibition),” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013), http://www.19thc- artworldwide.org/spring13/leininger-miller-reviews-henry-ossawa-tanner-modern-spirit- exhibition. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Leininger-Miller: Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit (exhibition) Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013) Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts January 28–April 15, 2012 Cincinnati Art Museum May 26–September 9, 2012 Houston Museum of Fine Arts October 14, 2012–January 6, 2013 “Mr. Tanner is not only a biblical painter, but he has brought to modern art a new spirit.” — Vance Thompson, “American Artists in Paris,” Cosmopolitan 29, no. 1 (May 1900): 19. Last summer the Cincinnati Art Museum (CAM) hosted a handsome exhibition of more than one hundred works by Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937), promoting the expatriate American artist in France as a “modern spirit.” Celebrated as a Biblical and landscape painter who was trained in late nineteenth-century academic aesthetics, Tanner was an exemplary draftsman whose large figurative canvases won acclaim at the