Quid Est Veritas?: Early Twentieth Century Styles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Collection of Ekphrastic Poems

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects Honors Program 5-2010 Manuscripts, Illuminated: A Collection of Ekphrastic Poems Jacqueline Vienna Goates Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Goates, Jacqueline Vienna, "Manuscripts, Illuminated: A Collection of Ekphrastic Poems" (2010). Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects. 50. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honors/50 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Capstone Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Manuscripts, Illuminated: A Collection of Ekphrastic Poems by Jacquelyn Vienna Goates Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of HONORS IN UNIVERSITY STUDIES WITH DEPARTMENTAL HONORS in English in the Department of Creative Writing Approved: Thesis/Project Advisor Departmental Honors Advisor Dr. Anne Shifrer Dr. Joyce Kinkead Director of Honors Program Dr. Christie Fox UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT Spring 2010 Abstract This thesis is a unique integration of creative writing and research of a specific literary tradition. As a student of art history and literature, and a creative writer, I am interested in fusing my interests by writing about art and studying the relationships between text and image. I have written a collection of ekphrastic poems, poems which are based on works of art. After reading extensively in this genre of poetry and researching its origins and evolution throughout literary history, I have come to a greater appreciation for those who write ekphrasis and what it can accomplish in the craft of writing. -

Don Quixote and Legacy of a Caricaturist/Artistic Discourse

Don Quixote and the Legacy of a Caricaturist I Artistic Discourse Rupendra Guha Majumdar University of Delhi In Miguel de Cervantes' last book, The Tria/s Of Persiles and Sigismunda, a Byzantine romance published posthumously a year after his death in 1616 but declared as being dedicated to the Count of Lemos in the second part of Don Quixote, a basic aesthetie principIe conjoining literature and art was underscored: "Fiction, poetry and painting, in their fundamental conceptions, are in such accord, are so close to each other, that to write a tale is to create pietoríal work, and to paint a pieture is likewise to create poetic work." 1 In focusing on a primal harmony within man's complex potential of literary and artistic expression in tandem, Cervantes was projecting a philosophy that relied less on esoteric, classical ideas of excellence and truth, and more on down-to-earth, unpredictable, starkly naturalistic and incongruous elements of life. "But fiction does not", he said, "maintain an even pace, painting does not confine itself to sublime subjects, nor does poetry devote itself to none but epie themes; for the baseness of lífe has its part in fiction, grass and weeds come into pietures, and poetry sometimes concems itself with humble things.,,2 1 Quoted in Hans Rosenkranz, El Greco and Cervantes (London: Peter Davies, 1932), p.179 2 Ibid.pp.179-180 Run'endra Guha It is, perhaps, not difficult to read in these lines Cervantes' intuitive vindication of the essence of Don Quixote and of it's potential to generate a plural discourse of literature and art in the years to come, at multiple levels of authenticity. -

Empirically Identify and Analyze Trained and Untrained Observers

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 052 219 24 TE 499 825 AUTHOR Hardiman, George W. TITLE Identification and Evaluation of Trained and Untrained Observers' Affective Responses to Art Ob'ects. Final Report. INSTITUTION Illinois Univ., Urbana. Dept. of Art. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education (DREW), Washington, D.C. Bureau of Research. BUREAU NO BR-9-0051 PUB DATE Mar 71 GRANT OEG-5-9-230051-0027 NOTE 113p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.65 HC-$6.58 DESCRIPTORS *Affective Behavior, *Art Expression, *Color Presentation, *Data Analysis, Factor Analysis, *Measurement Instruments, Rating Scales ABSTRACT The objectives of this study were twofold: (1) to empirically identify and analyze trained and untrained observers affective responses to a representative collection of paintings for the purpose et constructing art differential instruments, and (2) to use these instruments to objectively identify and evaluate the major affective factors and components associated with selected paintings by trained and untrained observers. The first objective was accomplished by having 120 trained and 120 untrained observers elicit a universe of 12,450 adjective qualifiers to a collection of 209 color slides of paintings. Data analyses yielded subsets of adjective qualifiers most characteristic of trained and untrained observers' affective decoding of the 209 slides. These subsets served as a basis for constructing separate art differential instruments for trained and untrained observers' use in subsequent analyses. The second objective was achieved by having 48 trained and 48 untrained observers rate 24 color slides of paintings on 50 scale art differential instruments. Trained and untrained observers' art differential ratings of the 24 paintings were factor analyzed in order to identify the major affective factors associated with the paintings. -

Henry Ossawa Tanner: Modern Spirit Exhibition, Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia

Review essay HenRy Ossawa TanneR: MOdeRn spiRiT exHibiTiOn, pennsylvania acadeMy Of fine aRTs, pHiladelpHia Alexia I. Hudson he Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) is located in Philadelphia within walking distance of City Hall. Founded in T1805 by painter and scientist Charles Willson Peale, sculptor William Rush, and other artists and business leaders, PAFA holds the distinction of being the oldest art school and art museum in the United States. Its current “historic landmark” build- ing opened in 1876, three years before Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937) enrolled as one of PAFA’s first African American students. Tanner would later become the first African American artist to achieve international acclaim for his work. Today, PAFA is comprised of two adjacent buildings—the “historic landmark” building at 118 North Broad Street and the Samuel M. V. Hamilton Building at 128 N. Broad Street. The oldest building was designed by architects Frank Furness and George W. Hewitt and has been designated a National Historic Landmark, hence its name. In 1976 PAFA underwent a delicately managed restoration process to ensure that the archi- tectural and historical integrity of the building was maintained. pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 79, no. 2, 2012. Copyright © 2012 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Wed, 14 Mar 2018 15:39:34 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms PAH 79.2_06_Hudson.indd 238 18/04/12 12:28 AM review essays The Lenfest Plaza opened adjacent to PAFA on October 1, 2011, and was celebrated with the inaugural lighting of “Paint Torch,” a sculpture by inter- nationally renowned American artist Claes Oldenburg. -

A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations December 2014 The ubiC st's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912 Geoffrey David Schwartz University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Schwartz, Geoffrey David, "The ubC ist's View of Montmartre: A Stylistic and Contextual Analysis of Juan Gris' Cityscape Imagery, 1911-1912" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 584. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/584 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTRE: A STYISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912. by Geoffrey David Schwartz A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Art History at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee December 2014 ABSTRACT THE CUBIST’S VIEW OF MONTMARTE: A STYLISTIC AND CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF JUAN GRIS’ CITYSCAPE IMAGERY, 1911-1912 by Geoffrey David Schwartz The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2014 Under the Supervision of Professor Kenneth Bendiner This thesis examines the stylistic and contextual significance of five Cubist cityscape pictures by Juan Gris from 1911 to 1912. These drawn and painted cityscapes depict specific views near Gris’ Bateau-Lavoir residence in Place Ravignan. Place Ravignan was a small square located off of rue Ravignan that became a central gathering space for local artists and laborers living in neighboring tenements. -

Press Information

PRESS INFORMATION PICASSO IN ISTANBUL SAKIP SABANCI MUSEUM, ISTANBUL 24 November 2005 to 26 March 2006 Press enquiries: Erica Bolton and Jane Quinn 10 Pottery Lane London W11 4LZ Tel: 020 7221 5000 Fax: 020 7221 8100 [email protected] Contents Press Release Chronology Complete list of works Biographies 1 Press Release Issue: 22 November 2005 FIRST PICASSO EXHIBITION IN TURKEY IS SELECTED BY THE ARTIST’S GRANDSON Picasso in Istanbul, the first major exhibition of works by Pablo Picasso to be staged in Turkey, as well as the first Turkish show to be devoted to a single western artist, will go on show at the Sakip Sabanci Museum in Istanbul from 24 November 2005 to 26 March 2006. Picasso in Istanbul has been selected by the artist‟s grandson Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Marta-Volga Guezala. Picasso expert Marilyn McCully and author Michael Raeburn are joint curators of the exhibition and the catalogue, working together with Nazan Olçer, Director of the Sakip Sabanci Museum, and Selmin Kangal, the museum‟s Exhibitions Manager. The exhibition will include 135 works spanning the whole of the artist‟s career, including paintings, sculptures, ceramics, textiles and photographs. The works have been loaned from private collections and major museums, including the Picasso museums in Barcelona and Paris. The exhibition also includes significant loans from the Fundaciñn Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte. A number of rarely seen works from private collections will be a special highlight of the exhibition, including tapestries of “Les Demoiselles d‟Avignon” and “Les femmes à leur toilette” and the unique bronze cast, “Head of a Warrior, 1933”. -

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

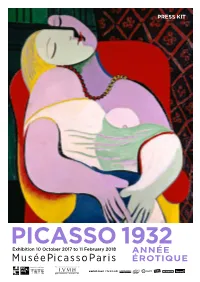

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

3"T *T CONVERSATIONS with the MASTER: PICASSO's DIALOGUES

3"t *t #8t CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MASTER: PICASSO'S DIALOGUES WITH VELAZQUEZ THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Joan C. McKinzey, B.F.A., M.F.A. Denton, Texas August 1997 N VM*B McKinzey, Joan C., Conversations with the master: Picasso's dialogues with Velazquez. Master of Arts (Art History), August 1997,177 pp., 112 illustrations, 63 titles. This thesis investigates the significance of Pablo Picasso's lifelong appropriation of formal elements from paintings by Diego Velazquez. Selected paintings and drawings by Picasso are examined and shown to refer to works by the seventeenth-century Spanish master. Throughout his career Picasso was influenced by Velazquez, as is demonstrated by analysis of works from the Blue and Rose periods, portraits of his children, wives and mistresses, and the musketeers of his last years. Picasso's masterwork of High Analytical Cubism, Man with a Pipe (Fort Worth, Texas, Kimbell Art Museum), is shown to contain references to Velazquez's masterpiece Las Meninas (Madrid, Prado). 3"t *t #8t CONVERSATIONS WITH THE MASTER: PICASSO'S DIALOGUES WITH VELAZQUEZ THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS By Joan C. McKinzey, B.F.A., M.F.A. Denton, Texas August 1997 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author would like to acknowledge Kurt Bakken for his artist's eye and for his kind permission to develop his original insight into a thesis. -

Press Dossier

KEES VAN DONGEN From 11th June to 27th September 2009 PRESS CONFERENCE 11th June 2009, at 11.30 a.m. INAUGURATION 11th June 2009, at 19.30 p.m. Press contact: Phone: + 34 93 256 30 21 /26 Fax: + 34 93 315 01 02 [email protected] CONTENTS 1. PRESENTATION 2. EXHIBITION TOUR 3. EXHIBITION AREAS 4. EXTENDED LABELS ON WORKS 5. CHRONOLOGY 1. PRESENTATION This exhibition dedicated to Kees Van Dongen shows the artist‘s evolution from his student years to the peak of his career and evokes many of his aesthetic ties and exchanges with Picasso, with whom he temporarily shared the Bateau-Lavoir. Born in a suburb of Rotterdam, Van Dongen‘s career was spent mainly in Paris where he came to live in 1897. A hedonist and frequent traveller, he was a regular visitor to the seaside resorts of Deauville, Cannes and Monte Carlo, where he died in 1968. Van Dongen experienced poverty, during the years of revelry with Picasso, and then fame before finally falling out of fashion, a status he endured with a certain melancholy. The exhibition confirms Kees Van Dongen‘s decisive role in the great artistic upheavals of the early 20th century as a member of the Fauvist movement, in which he occupied the unique position of an often irreverent and acerbic portraitist. The virulence and extravagance of his canvases provoked immediate repercussions abroad, particularly within the Die Brücke German expressionist movement. Together with his orientalism, contemporary with that of Matisse, this places Van Dongen at the very forefront of the avant-garde. -

The Study of the Relationship Between Arnold Schoenberg and Wassily

THE STUDY OF THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ARNOLD SCHOENBERG AND WASSILY KANDINSKY DURING SCHOENBERG’S EXPRESSIONIST PERIOD D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sohee Kim, B.M., M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2010 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Donald Harris, Advisor Professor Jan Radzynski Professor Arved Mark Ashby Copyright by Sohee Kim 2010 ABSTRACT Expressionism was a radical form of art at the start of twentieth century, totally different from previous norms of artistic expression. It is related to extremely emotional states of mind such as distress, agony, and anxiety. One of the most characteristic aspects of expressionism is the destruction of artistic boundaries in the arts. The expressionists approach the unified artistic entity with a point of view to influence the human subconscious. At that time, the expressionists were active in many arts. In this context, Wassily Kandinsky had a strong influence on Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg‟s attention to expressionism in music is related to personal tragedies such as his marital crisis. Schoenberg solved the issues of extremely emotional content with atonality, and devoted himself to painting works such as „Visions‟ that show his anger and uneasiness. He focused on the expression of psychological depth related to Unconscious. Both Schoenberg and Kandinsky gained their most significant artistic development almost at the same time while struggling to find their own voices, that is, their inner necessity, within an indifferent social environment. Both men were also profound theorists who liked to explore all kinds of possibilities and approached human consciousness to find their visions from the inner world. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Dossiê Kandinsky Kandinsky Beyond Painting: New Perspectives

dossiê kandinsky kandinsky beyond painting: new perspectives Lissa Tyler Renaud Guest Editor DOI: https://doi.org/10.26512/dramaturgias.v0i9.24910 issn: 2525-9105 introduction This Special Issue on Kandinsky is dedicated to exchanges between Theatre and Music, artists and researchers, practitioners and close observers. The Contents were also selected to interest and surprise the general public’s multitudes of Kandinsky aficionados. Since Dr. Marcus Mota’s invitation in 2017, I have been gathering scholarly, professional, and other thoughtful writings, to make of the issue a lively, expansive, and challenging inquiry into Kandinsky’s works, activities, and thinking — especially those beyond painting. “Especially those beyond painting.” Indeed, the conceit of this issue, Kandinsky Beyond Painting, is that there is more than enough of Kandinsky’s life in art for discussion in the fields of Theatre, Poetry, Music, Dance and Architecture, without even broaching the field he is best known for working in. You will find a wide-ranging collection of essays and articles organized under these headings. Over the years, Kandinsky studies have thrived under the care of a tight- knit group of intrepid scholars who publish and confer. But Kandinsky seems to me to be everywhere. In my reading, for example, his name appears unexpectedly in books on a wide range of topics: philosophy, popular science, physics, neuroscience, history, Asian studies, in personal memoirs of people in far-flung places, and more. Then, too, I know more than a few people who are not currently scholars or publishing authors evoking Kandinsky’s name, but who nevertheless have important Further Perspectives, being among the most interesting thinkers on Kandinsky, having dedicated much rumination to the deeper meanings of his life and work.