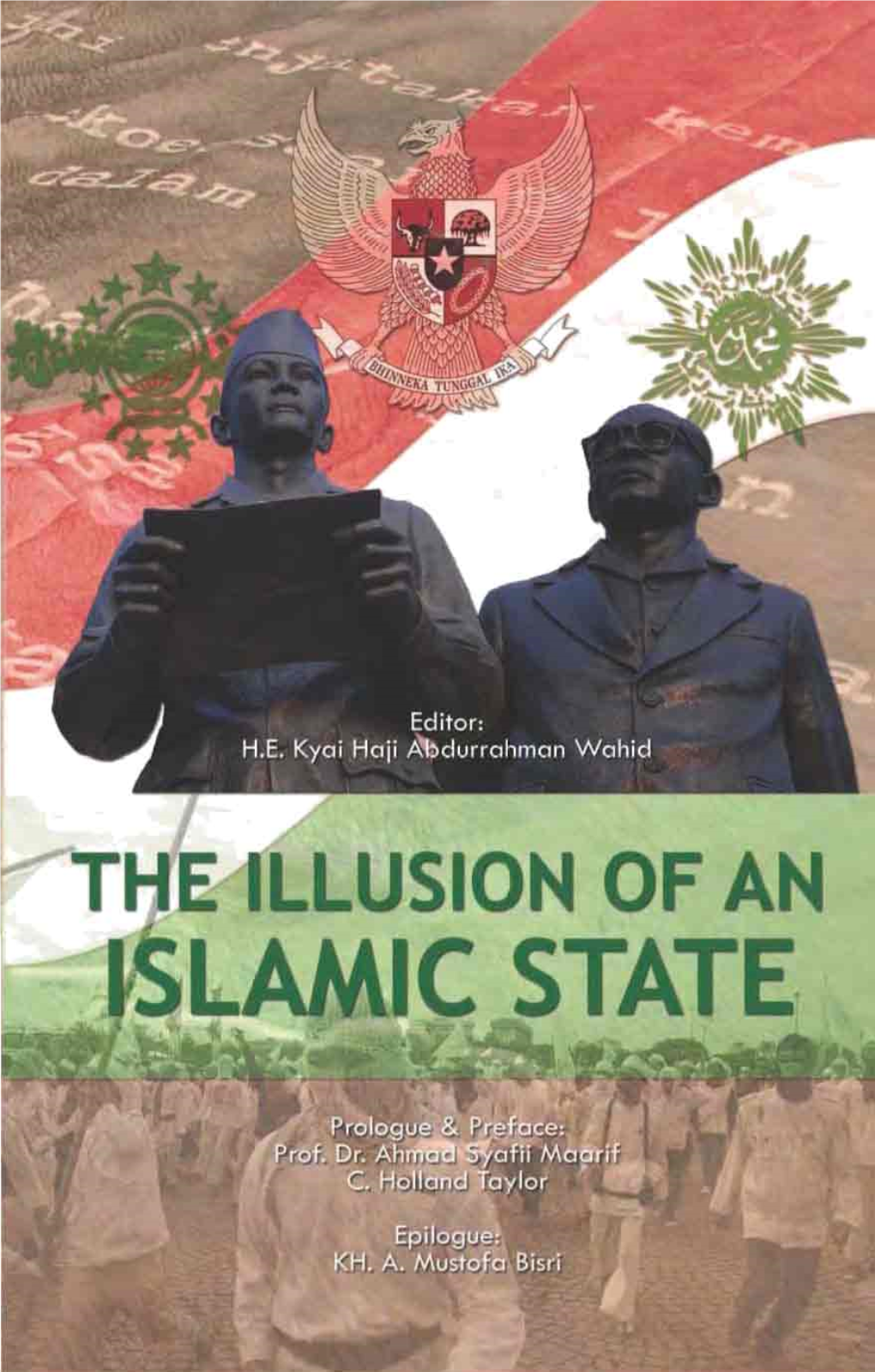

The Illusion of an Islamic State

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RADICALIZING INDONESIAN MODERATE ISLAM from WITHIN the NU-FPI Relationship in Bangkalan, Madura

RADICALIZING INDONESIAN MODERATE ISLAM FROM WITHIN The NU-FPI Relationship in Bangkalan, Madura Ahmad Zainul Hamdi IAIN Sunan Ampel, Surabaya - Indonesia Abstract: This article tries to present the most current phenomenon of how moderate Islam can live side by side with radical Islam. By focusing its analysis on the dynamics of political life in Bangkalan, Madura, the paper argues that the encounter between these two different ideological streams is possible under particular circumstances. First, there is a specific political situation where the moderate Islam is able to control the political posts. Second, there is a forum where they can articulate Islamic ideas in terms of classical and modern political movements. This study has also found out that the binary perspective applied in the analysis of Islamic movement is not always relevant. The fact, as in the case of Bangkalan, is far more complex, in which NU and Islamic Defender Front (FPI) can merge. This is so Eecause at the Eeginning, F3,’s management in the city is led by kyais or/and prominent local NU leaders. Keywords: Radicalization, de-radicalization, moderate Islam, radical Islam. Introduction A discussion on the topic of contemporary Islamic movements is filled with various reviews about radical Islam. As news, academic work also has its own actual considerations. The September 11th incident seems to be a “productive” momentum to tap a new academic debate which was previously conducted only by a few people who were really making Islam and its socio-political life as an academic project. Islamism, in its violence and atrocity, then became a popular theme that filled almost all the scientific discussion that took ideology and contemporary Islamic movements as a main topic. -

Pandangan Front Pembela Islam ( Fpi) Terhadap Islam Nusantara

PANDANGAN FRONT PEMBELA ISLAM ( FPI) TERHADAP ISLAM NUSANTARA SKRIPSI Diajukan unttuk memenuhi salah satu syarat memperoleh gelar Sarjana Agama (S.Ag) Disusun Oleh: Riza Adi Putra 11150321000020 PROGRAM STUDI STUDI AGAMA-AGAMA FAKULTAS USHULUDDIN UNIVERSITAS ISLAM NEGERI SYARIF HIDAYATULLAH JAKARTA 2020 M/1441 H LEMBAR PERNYATAAN Saya yang bertanda tangan di bawah ini: Nama : Riza Adi Putra NIM : 11150321000020 Prodi : Studi Agama-Agama Fakultas : Ushuluddin Judul Skripsi :PANDANGAN FRONT PEMBELA ISLAM (FPI) TERHADAP ISLAM NUSANTARA Dengan ini saya menyatakan bahwa: 1. Skripsi ini merupakan hasil karya saya yang diajukan untuk memenuhi salah satu persyaratan memperoleh gelar Sarjana Agama (S.Ag) di UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. 2. Semua sumber yang saya gunakan dalam penulisan ini telah saya cantumkan sesuai dengan ketentuan yang berlaku di UIN Syarrif Hidayatullah Jakarta. 3. Jika kemudian hari terbukti bahwa saya atau merupakan hasil jiplakan dari karya orang lain, maka saya bersedia menerima sanksi yang berlaku di UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta. Demikian pernyataan ini saya buat dengan sebenar-benarnya. ii iii iv ABSTRAK Riza Adi Putra Judul Skripsi: Pandangan Front Pembela Islam (FPI) Terhadap Islam Nusantara Islam Nusantara atau yang biasa disebut dengan Islam di Indonesia merupakan hasil dari dialog antara ajaran Islam dengan budaya lokal. Dengan demikian, hal tersebut akan menghasilkan budaya yang Islami, sehingga Islam Nusantara dipandang sebagai Islam dengan kearifan lokal. Di samping itu Islam Nusantara merupakan sebuah keberhasilan dari para ulama dalam menyebarkan ajaran Islam di Indonesia. Seiring dengan berkembangnya Islam di Indonesia lahir beberapa gerakan Islam dengan karakternya masing-masing. Seperti Nahdlatul Ulama dengan karakternya yang tradisional, Muhammadiyah dengan Modernis dan Front Pembela Islam (FPI) dengan gerakan amar ma’ruf nahi munkar. -

Download (1MB)

BAB I PENDAHULUAN A. Latar Belakang Masalah Masyarakat Indonesia merupakan masyarakat yang berasal dari berbagai macam latar belakang, tidak hanya dari berbagai macam agama seperti Islam, Kristen, Hindu, Buddha, Konghucu dan juga aliran kepercayaan. Tetapi masyarakat Indonesia merupakan masyarakat yang juga memiliki berbagai macam tradisi, adat istiadat dan juga kebudayaan sebagai ciri khas masing-masing wilayah mereka. Kebudayaan adalah keseluruhan dari kehidupan manusia yang terpola dan didapatkan dengan belajar atau yang diwariskan kepada generasi berikutnya, baik yang masih dalam pikiran, perasaan, dan hati pemiliknya (Agus, 2006: 35). Sebagai peninggalan yang diwariskan oleh leluhur dan nenek moyang kepada masyarakat yang sekarang, kebudayaan masih terus dilestarikan dengan cara melaksanakan apa yang telah diwariskan. Tentu saja kebudayaan itu memiliki makna dan tujuan yang baik serta mengandung nilai- nilai serta norma sehingga kebudayaan itu masih terus dilaksanakan hingga sekarang. Manusia dan kebudayaan merupakan hal yang tidak dapat dipisahkan. Sekalipun manusia sebagai pendukung kebudayaan akan mati namun kebudayaan yang dimilikinya akan tetap ada dan akan diwariskan pada keturunannya dan demikian seterusnya (Poerwanto, 2000: 50). Dengan beragamnya kebudayaan yang dimiliki oleh Indonesia maka dari kebudayaan 1 2 inilah diharapkan akan tercipta suatu masyarakat yang memiliki hubungan baik dalam kehidupannya serta tidak memandang dari latar belakang agama, ras, suku dan sebagainya. Dari sinilah manusia menjadi bagian penting dalam lestarinya kebudayaan tersebut. Dalam hal ini, masyarakat apabila dilihat dari segi budaya memiliki peran penting dalam pelestarian budaya. Dimana unsur- unsur yang dimiliki oleh kebudayaan ada tiga hal yakni; norma, nilai, keyakinan yang ada dalam pikiran, hati dan perasaan manusia. Kemudian tingkah laku yang dapat diamati dalam kehidupan nyata dan hasil material dan kreasi, pikiran, dan perasaan manusia (Koentjaraningrat, 2000: 179-202). -

Islamic Militancy, Sharia, and Democratic Consolidation in Post‑Suharto Indonesia

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Islamic militancy, Sharia, and democratic consolidation in post‑Suharto Indonesia Noorhaidi Hasan 2007 Noorhaidi Hasan. (2007). Islamic militancy, Sharia, and democratic consolidation in post‑Suharto Indonesia. (RSIS Working Paper, No. 143). Singapore: Nanyang Technological University. https://hdl.handle.net/10356/79795 Nanyang Technological University Downloaded on 28 Sep 2021 12:00:43 SGT ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library No. 143 Islamic Militancy, Sharia, and Democratic Consolidation in Post-Suharto Indonesia Noorhaidi Hasan S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies Singapore 23 October 2007 With Compliments This Working Paper series presents papers in a preliminary form and serves to stimulate comment and discussion. The views expressed are entirely the author’s own and not that of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies ATTENTION: The Singapore Copyright Act applies to the use of this document. Nanyang Technological University Library The S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) was established in January 2007 as an autonomous School within the Nanyang Technological University. RSIS’s mission is to be a leading research and graduate teaching institution in strategic and international affairs in the Asia Pacific. To accomplish this mission, it will: • Provide a rigorous professional graduate education in international affairs with a strong practical and area emphasis • Conduct policy-relevant research in national security, defence and strategic studies, diplomacy and international relations • Collaborate with like-minded schools of international affairs to form a global network of excellence Graduate Training in International Affairs RSIS offers an exacting graduate education in international affairs, taught by an international faculty of leading thinkers and practitioners. -

Interna Tional Edition

Number 7 2014 ISSN 2196-3940 INTERNATIONAL Saudi Arabia Exporting Salafi Education and Radicalizing Indonesia’s Muslims Amanda Kovacs Salafis, who defend a very conservative, literal interpretation of Islam and treat Shia Muslims with hostility, are not just a phenomenon in the Middle East. They are increasingly pressuring Shias and other religious minorities in Indonesia, too. Analysis Saudi Arabia is the world’s main provider of Islamic education. In addition to promoting Salafism and maligning other religious communities, Saudi educational materials present the kingdom in a favorable light and can also exacerbate religious strife, as they are doing in Indonesia. The Saudi educational program aims to create global alliances and legitimize the Saudi claim to be the leader of Islam – at home and abroad. Since switching to democracy in 1998, Indonesia has been shaken time and EDITION again by Salafi religious discrimination and violence, often on the part of graduates of LIPIA College in Jakarta, which was founded by Saudi Arabia in 1980. Domestically, Saudi Arabia uses educational institutions to stabilize the system; since the 1960s, it has become the largest exporter of Islamic education. After Saudi Arabia began to fight with Iran for religious hegemony in 1979, it founded schools and universities worldwide to propagate its educational traditions. In Jakarta, LIPIA represents a Saudi microcosm where Salafi norms and traditions prevail. LIPIA not only helps Saudi Arabia to influence Indonesian English society, it also provides a gateway to all of Southeast Asia. As long as Muslim societies fail to create attractive government-run educational institutions for their citizens, there will be ample room for Saudi influence. -

Nahdhatul Ulama: from Traditionalist to Modernist Anzar Abdullah

Nahdhatul Ulama: from traditionalist to modernist Anzar Abdullah, Muhammad Hasbi & Harifuddin Halim Universitas Islam Makassar Universitas Bosowa (UNIBOS) Makassar [email protected] Abstract This article is aimed to discuss the change shades of thought in Nahdhatul Ulama (NU) organization, from traditionalist to modernist. This is a literature study on thought that develop within related to NU bodies with Islamic cosmopolitanism discourse for interact and absorb of various element manifestation cultural and insight scientist as a part from discourse of modernism. This study put any number figures of NU as subject. The results of the study show that elements thought from figure of NU, like Gusdur which includes effort eliminate ethnicity, strength plurality culture, inclusive, liberal, heterogeneity politics, and life eclectic religion, has been trigger for the birth of the modernism of thought in the body of NU. It caused change of religious thought from textual to contextual, born in freedom of thinking atmosphere. Keywords: Nahdhatul Ulama, traditionalist, modernist, thought, organization Introduction The dynamic of Islamic thought that continues to develop within the NU organization in the present context, it is difficult to say that NU is still traditional, especially in the area of religious thought. This can be seen in the concept of inclusivism, cosmopolitanism, and even liberalism developed by NU figures such as Abdurrahman Wahid, Achmad Siddiq, and some young NU figures, such as Ulil Absar Abdalla. This shows a manifestation of modern thought. Critical thinking as a feature of modernism seems to have become the consumption of NU activists today. Therefore, a new term emerged among those called "re- interpretation of ahlussunah-waljamaah" and the re-interpretation of the concept of "bermazhab" or sect. -

I PESAN DAKWAH KH. ABDULLAH GYMNASTIAR DALAM

PESAN DAKWAH KH. ABDULLAH GYMNASTIAR DALAM PERSPEKTIF TASAWUF Oleh : DIANA SARI NIM: 16205010076 TESIS Diajukan kepada Program Studi Magister (S2) Aqidah dan Filsafat Islam Fakultas Ushuluddin dan Pemikiran Islam UIN Sunan Kalijaga untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat guna Memperoleh Gelar Magister Agama YOGYAKARTA 2019 i ii iii iv v vi MOTTO َﻓﺈِ ﱠﻥ َﻣ َﻊ ٱۡ ﻟ ﻌُ ۡ ﺴ ِ ﺮ ﻳُ ۡ ﺴ ً ﺮﺍ ﺮ (Karena Sesungguhnya sesudah kesulitan itu ada kemudahan) Aku tidak tahu sisa umurku, tapi yang paling penting aku bersamamu sepanjang hidupku, mati dalam cinta Mu. Life is like riding a bicycle. To keep your balance, you must keep moving.~Albert Einstein I have no special talents, i am only passionately curious. ~ Albert Einstein vii HALAMAN PERSEMBAHAN Karya ini dipersembahkan kepada kedua orang tua saya (Sukasri Wijaya dan Surina) Karya ini juga dipersembahkan untuk teman-teman seangkatan AFI (Aqidah dan Filsafat Islam) Angkatan 2016 semester genap Kepada “Kampus Peradaban” Universitas Islam Negeri Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta viii ABSTRAK Kebangkitan Tasawuf saat ini mulai menunjukkan eksistensi yang baru di Indonesia. Tasawuf tidak hanya dipahami sebagai ajaran-ajaran sufi dan institusi tradisional (tarekat). Gairah baru dalam sufisme di Indonesia telah terlihat di kota-kota dan di antara kelas-kelas menengah. Penelitian Howell menunjukkan kebangkitan sufi yang dipromosikan melalui dua jalan (1) para ulama yang mendapat pendidikan Islam tradisional yang berkomunikasi dengan para pengikutnya dikelas-kelas pendidikan (2) para pendakwah televisi menggunakan siaran-siarannya yang diatur dan didramatisasikan di depan jemaah. Nuansa baru dengan membumikan nilai-nilai sufistik ini juga dilakukan oleh tokoh KH.Abdullah Gymnastiar yang menghubungkan pengalaman spiritualnya dengan dunia sufi. -

Saudi Strategies for Religious Influence and Soft Power in Indonesia

12 2 July 2020 Saudi Strategies for Religious Influence and Soft Power in Indonesia Jarryd de Haan Research Analyst Indo-Pacific Research Programme Key Points Saudi Arabia’s push for religious influence in Indonesia has primarily taken shape through educational facilities, which remain the key source of influence today. Evidence of Saudi influence can also be seen through a trend of the “Arabisation” of Islam in Indonesia, as well as pressure on the Indonesian Government to maintain its hajj quota. Indonesian Muslim groups that object to the Salafist doctrine will continue to act as a brake on Saud i religious influence. Pancasila and, more broadly, nationalism, could also be used by those seeking to limit Saudi influence in the future. The long-term implications are less clear, but it is likely that Indonesia will continue to see elements of its own society continue to push for the adoption of more conservative policies and practices. Summary Saudi Arabia has a long history of exporting its brand of Islam across the globe as a tool of religious soft power influence and as a means to counter the influence of its rival, Iran. Indonesia, a country which contains the largest Muslim population in the world, has been at the receiving end of that influence for decades. This paper examines the origins of Saudi religious influence in Indonesia, the obstacles to that influence and identifies some of the implications that it may have for Indonesian society in the long-term future. Analysis Historical Saudi Religious Influence Saudi Arabia’s efforts to increase its religious influence in Indonesia coincided with an Islamic revival throughout South-East Asia in the late 1970s. -

The Rise of Islamism and the Future of Indonesian Islam

Journal of International Studies Vol. 16, 105-128 (2020) How to cite this article: Al Qurtuby, S. (2020). The rise of Islamism and the future of Indonesian Islam. Journal of International Studies, 16, 105-128. https://doi.org/10.32890/jis2020.16.7 The Rise of Islamism and the Future of Indonesian Islam Sumanto Al Qurtuby Department of Global & Social Studies College of General Studies King Fahd University of Petroleum & Minerals [email protected] Received: 6/4/2020 Revised: 28/6/2020 Accepted: 12/7/2020 Published: 30/12/2020 Abstract Since the downfall of Suharto’s dictatorial regime in 1998, Indonesia has witnessed a surge of various Islamist groups that have potentially threatened the country’s religious tolerance, civil Islam, and civic pluralism. Moreover, it is suggested that the rise of Islamist groups could likely transform Indonesia into an intolerant Islamist country. However, this article asserts that the Islamist groups are unlikely to reform Indonesia into an Islamic State or Sharia–based government and society, and are unable to receive the support and approval of the Indonesian Muslim majority due to the following fundamental reasons: the groups’ internal and inherent weaknesses, ruptured alliance among the groups, lack of Islamist political parties, limited intellectual grounds of the movement, the accommodation of some influential Muslim clerics and figures into the central government body, and public opposition toward the Islamist groups. Keywords: Islamism, Islamist movement, civil Islam, Muslim society, Islamist radicalism, peaceful Islamist mobilization, religious pluralism. Introduction One of the consequences observed in Indonesia after the downfall of Suharto in May, 1998 was the surge in Islamism. -

RAPPROCHEMENT BETWEEN SUNNISM and SHIISM in INDONESIA Challenges and Opportunities

DOI: 10.21274/epis.2021.16.1.31-58 RAPPROCHEMENT BETWEEN SUNNISM AND SHIISM IN INDONESIA Challenges and Opportunities Asfa Widiyanto IAIN Salatiga, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract Throughout Islamic history, we observe enmity and conflicts between Sunnism and Shiism, nonetheless there has been also reconciliation between these sects. This article examines the opportunities and challenges of Sunni-Shia convergence in Indonesia. Such a picture will reveal a better understanding of the features of Sunni-Shia convergence in the country and their relationship with the notion of ‘Indonesian Islam’. The hostility between Shiism and Sunnism in Indonesia is triggered by misunderstandings between these sects, politicisation of Shiism, as well as geopolitical tensions in the Middle East. These constitute the challenges of Sunni-Shia convergence. One may also observe the ventures of Sunni-Shia convergence which have been undertaken by the scholars of the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and Muhammadiyah, and other Islamic civil society organisations. Grounding on these enterprises and the enduring elaboration of ‘Indonesian Islam’, the opportunities of and the prospects for Sunni-Shia rapprochement in the country are envisaged. [Sepanjang sejarah Islam, kita dapat dengan mudah menyaksikan serangkaian pertikaian dan konflik antara kelompok Syiah dan Sunni. Namun demikian, terdapat pula serangkaian kisah rekonsiliasi antarkeduanya. Artikel ini akan mendiskusikan peluang dan tantangan dalam mendamaikan kedua kelompok tersebut di Indonesia. Selain itu, artikel ini juga memberikan Asfa Widiyanto: Rapprochement between Sunnism and Shiism................. gambaran lebih jelas mengenai karakteristik konvergensi antara Syiah dan Sunni dan hubungan mereka dengan term “Islam Indonesia”. Perseteruan antara Syiah dan Sunni di Indonesia pada dasarnya disebabkan kesalah- pahaman antara keduanya, politisasi Syiah, sekaligus ketegangan politik di Timur Tengah. -

Saudi Arabia Exporting Salafi Education and Radicalizing Indonesia’S Muslims

Number 7 2014 ISSN 2196-3940 INTERNATIONAL Saudi Arabia Exporting Salafi Education and Radicalizing Indonesia’s Muslims Amanda Kovacs Salafis, who defend a very conservative, literal interpretation of Islam and treat Shia Muslims with hostility, are not just a phenomenon in the Middle East. They are increasingly pressuring Shias and other religious minorities in Indonesia, too. Analysis Saudi Arabia is the world’s main provider of Islamic education. In addition to promoting Salafism and maligning other religious communities, Saudi educational materials present the kingdom in a favorable light and can also exacerbate religious strife, as they are doing in Indonesia. The Saudi educational program aims to create global alliances and legitimize the Saudi claim to be the leader of Islam – at home and abroad. Since switching to democracy in 1998, Indonesia has been shaken time and EDITION again by Salafi religious discrimination and violence, often on the part of graduates of LIPIA College in Jakarta, which was founded by Saudi Arabia in 1980. Domestically, Saudi Arabia uses educational institutions to stabilize the system; since the 1960s, it has become the largest exporter of Islamic education. After Saudi Arabia began to fight with Iran for religious hegemony in 1979, it founded schools and universities worldwide to propagate its educational traditions. In Jakarta, LIPIA represents a Saudi microcosm where Salafi norms and traditions prevail. LIPIA not only helps Saudi Arabia to influence Indonesian English society, it also provides a gateway to all of Southeast Asia. As long as Muslim societies fail to create attractive government-run educational institutions for their citizens, there will be ample room for Saudi influence. -

FROM FLUID IDENTITIES to SECTARIAN LABELS a Historical Investigation of Indonesia’S Shi‘I Communities

Al-Jāmi‘ah: Journal of Islamic Studies Vol. 52, no. 1 (2014), pp. 101-126, doi: 10.14421/ajis.2014.521.101-126 FROM FLUID IDENTITIES TO SECTARIAN LABELS A Historical Investigation of Indonesia’s Shi‘i Communities Chiara Formichi Department of Asian Studies, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York email: [email protected] Abstract Since 2011 Indonesia has experienced a rise in intra-Muslim sectarian violence, with Shi‘a and Ahmadi communities becoming the target of radical Sunni groups. Taking as point of departure the attacks on Shi‘a Muslims and the rapid polarization of Sunni and Shi‘i identities, this article aims at deconstructing the “Shi‘a” category. Identifying examples of how since the early century of the Islamization devotion for the Prophet Muhammad and his progeny (herein referred to as ‘Alid piety) has been incorporated in the archipelago’s “Sunni” religious rituals, and contrasting them to programmatic forms of Shi’ism (adherence to Ja‘fari fiqh) which spread in the socio-political milieu of the 1970s-1990s. This article argues not only that historically there has been much devotional common ground between “Sunni” and “Shi‘a”, but also that in the last decade much polarization has occurred within the “Shi‘a” group between those who value local(ized) forms of ritual and knowledge, and those who seek models of orthopraxy and orthodoxy abroad. [Sejak tahun 2011, kekerasan bernuansa aliran dalam internal muslim di Indonesia mengalami peningkatan, dengan komunitas Syiah dan Ahmadiyah menjadi sasaran kekerasan dari kelompok-kelompok Sunni radikal. Berangkat dari kasus penyerangan terhadap kelompok Syiah dan cepatnya polarisasi identitas Sunni-Syiah, artikel ini berusaha mendekonstruksi kriteria “Syiah” di Indonesia.