Audio- Interview 2: Atlas Hardware (Edwards/Chen)

Total Page:16

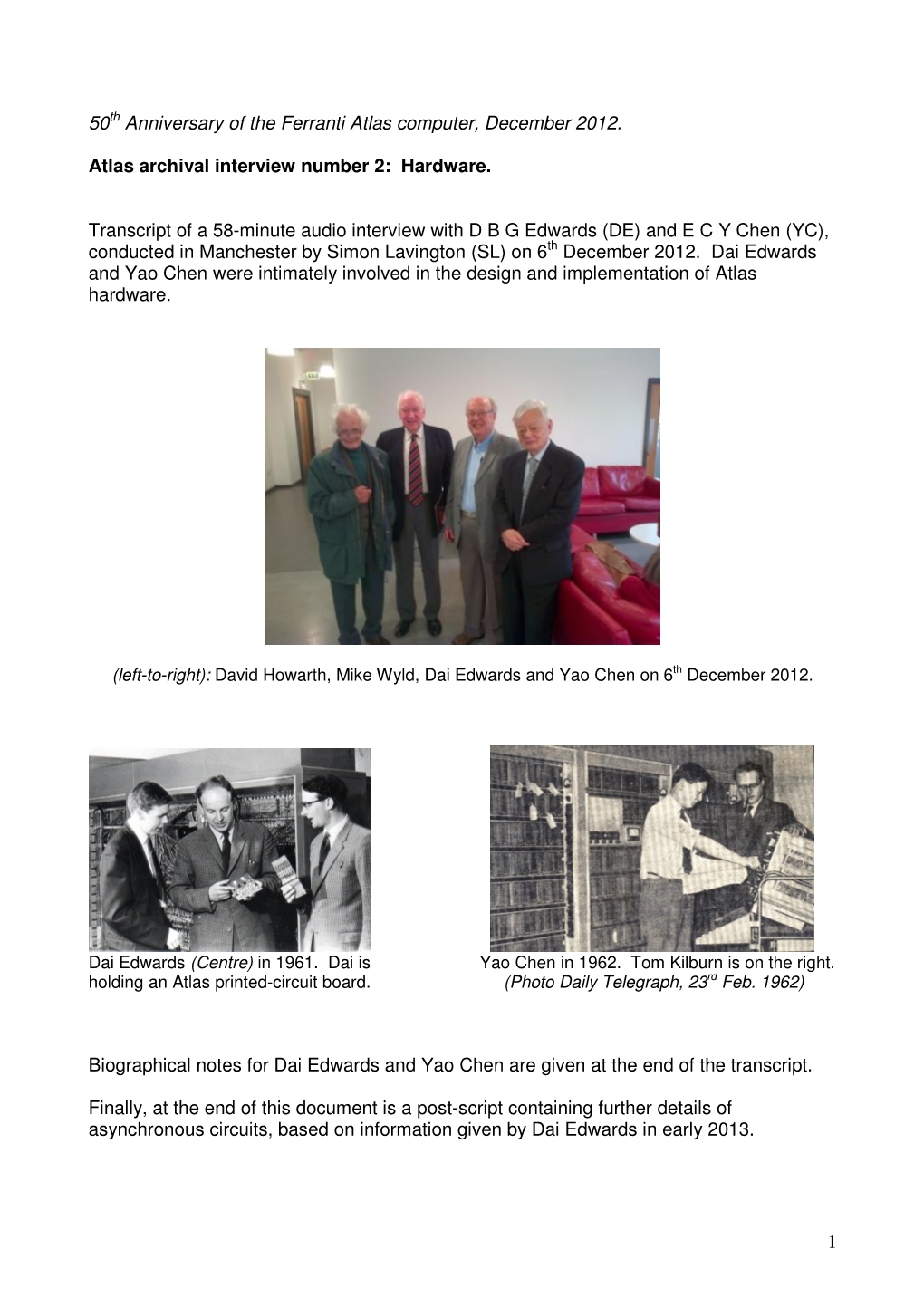

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Did What? Engineers Vs Mathematicians Title Page America Vs Europe Ideas Vs Implementations Babbage Lovelace Turing

Who did what? Engineers vs Mathematicians Title Page America vs Europe Ideas vs Implementations Babbage Lovelace Turing Flowers Atanasoff Berry Zuse Chandler Broadhurst Mauchley & Von Neumann Wilkes Eckert Williams Kilburn SlideSlide 1 1 SlideSlide 2 2 A decade of real progress What remained to be done? A number of different pioneers had during the 1930s and 40s Memory! begun to make significant progress in developing automatic calculators (computers). Thanks (almost entirely) to A.M. Turing there was a complete theoretical understanding of the elements necessary to produce a Atanasoff had pioneered the use of electronics in calculation stored program computer – or Universal Turing Machine. Zuse had mad a number of theoretical breakthroughs Not for the first time, ideas had outstripped technology. Eckert and Mauchley (with JvN) had produced ENIAC and No-one had, by the end of the war, developed a practical store or produced the EDVAC report – spreading the word memory. Newman and Flowers had developed the Colossus It should be noted that not too many people were even working on the problem. SlideSlide 3 3 SlideSlide 4 4 The players Controversy USA: Eckert, Mauchley & von Neumann – EDVAC Fall out over the EDVAC report UK: Maurice Wilkes – EDSAC Takeover of the SSEM project by Williams (Kilburn) UK: Newman – SSEM (what was the role of Colossus?) Discord on the ACE project and the departure of Turing UK: Turing - ACE EDSAC alone was harmonious We will concentrate for a little while on the SSEM – the winner! SlideSlide 5 5 SlideSlide 6 6 1 Newman & technology transfer: Secret Technology Transfer? the claim Donald Michie : Cryptanalyst An enormous amount was transferred in an extremely seminal way to the post war developments of computers in Britain. -

Social Construction and the British Computer Industry in the Post-World War II Period

The rhetoric of Americanisation: Social construction and the British computer industry in the Post-World War II period By Robert James Kirkwood Reid Submitted to the University of Glasgow for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economic History Department of Economic and Social History September 2007 1 Abstract This research seeks to understand the process of technological development in the UK and the specific role of a ‘rhetoric of Americanisation’ in that process. The concept of a ‘rhetoric of Americanisation’ will be developed throughout the thesis through a study into the computer industry in the UK in the post-war period . Specifically, the thesis discusses the threat of America, or how actors in the network of innovation within the British computer industry perceived it as a threat and the effect that this perception had on actors operating in the networks of construction in the British computer industry. However, the reaction to this threat was not a simple one. Rather this story is marked by sectional interests and technopolitical machination attempting to capture this rhetoric of ‘threat’ and ‘falling behind’. In this thesis the concept of ‘threat’ and ‘falling behind’, or more simply the ‘rhetoric of Americanisation’, will be explored in detail and the effect this had on the development of the British computer industry. What form did the process of capture and modification by sectional interests within government and industry take and what impact did this have on the British computer industry? In answering these questions, the thesis will first develop a concept of a British culture of computing which acts as the surface of emergence for various ideologies of innovation within the social networks that made up the computer industry in the UK. -

ATLAS@50 Then and Now

ATLAS@50 Then and now Science & Technology Facilities Council The origins of Atlas In the years following the Second World War, there was huge interest in nuclear physics technologies both for civilian nuclear energy research and for military nuclear weapons. These technologies required ever-increasing amounts of computer power to analyse data and, more importantly, to perform simulations far more safely than would be possible in a laboratory. By 1958, 75% of Britain’s R&D computer power was provided by the Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) at Aldermaston (using an American IBM 704), Risley, Winfrith and Harwell (each using a British Ferranti Mercury). These were however what we would now call The advisory panel for the super-computer single-user systems, capable of running only included Freddy Williams (a pioneer in radar and Foreword one program at a time, so were essentially very computer technology) from Victoria University large desktop calculators. Indeed, the name of Manchester, Maurice Wilkes (designer of It is now known as Rutherford Appleton Laboratory buildings R26 and R27, but over “computer” referred to the human operator; EDSAC, the Electronic Delay Storage Automatic its 50+ year history, the Atlas Computer Laboratory in the parish of Chilton has been the machinery itself was known as an Calculator) from Cambridge, Albert Uttley of the “automatic calculating machine.” RRE (Royal Radar Establishment), and Ted Cooke- part of many seminal moments in computing history. Yarborough (designer of the Dekatron and CADET British manufacturers of automatic calculating computers) from AERE Harwell; Christopher Over its 50+ year history it has also housed It was cleaned and restored as far as we could, machines were doing well until IBM announced Strachey (a pioneer in programming language many mainframe and super-computers including and took pride of place at an event held to that their first transistorised computer was to design) was in charge of design. -

ASAP 2020 Opinion

Message from the Conference Chairs ASAP 2020 We welcome you to the 31st IEEE International Conference on Application-specific Systems, Architectures and Processors (ASAP 2020). This year’s event was supposed to take place in Manchester, United Kingdom, a major city in the northwest of England with a rich industrial heritage. Manchester has transformed the modern world through a boom in textile manufacturing during the industrial revolution in Victorian England. In the 1880s, 80% of the world cotton production went through Manchester for trade and manufacturing, making Manchester the first industrialized city in the world. To master the enormous logistics, the 58 km Manchester Ship Canal connected Manchester with the Irish Sea in 1894, and the world’s first steam-powered, inter-urban railway for transporting both passengers and goods was completed between Manchester and Liverpool in 1830. Its Manchester terminus is now part of the Science and Industry Museum where we planed the ASAP 2020 banquet. ASAP 2020 is hosted by the Department of Computer Science at The University of Manchester, which is one of the oldest in the UK. The University of Manchester played an important role in the development of computing. This includes the development of the first electronically stored program computer, the first floating-point machine, and the Atlas computer, which was once the world’s most powerful computer and the first machine to use paged virtual memory. The school and department of Computer Science was home to Alan Turing and Tom Kilburn; and in November 2018, the 1 million processor SpiNNaker neuromorphic supercomputer went into service under the supervision of Steve Furber. -

Issue 3 January 2005 Ferranti Mercury X1 Index B3 Sales of Ferranti

Issue 3 January 2005 Ferranti Mercury X1 Index B3 Sales of Ferranti Mercury Computers etc D1 Design history and designers References Delivery etc Issue 3 January 2005 B3 Sales of Ferranti Mercury computers. Information mostly taken from: The Ferranti Computer Department – an informal history. B B Swann, 1975. Typescript for private circulation only. See the National Archive for the History of Computing, catalogue number NAHC/FER/C30. No. customer date del’d scientific applic’s. Commercial applic’s 1 Norwegian Defence Research Aug. ’57 Atomic energy work - Est., Kjeller. 2 Manchester University Oct. ’57 Research & service work - Transferred to University of Sheffield 1963 3 French Atomic Energy Nov. ’57 Atomic energy work - Authority, Saclay. 4 United Kingdom Atomic Feb. ’58 Atomic energy work - Energy Authority, Harwell. 5 RAF Meteorological Office, Sept. ’58 Weather forecasting - Dunstable. 6 Council for European Nuclear Jun. ’58 Atomic energy work - Research, Geneva. 7 London University. Oct. ’58 Research & service work - 8 United Kingdom Atomic Oct. ’58 Atomic energy work Energy Authority, Risley. 9 Oxford University. Nov. ’58 Research & service work - Forestry (large Dbs) Replaced by KDF9 10 Shell International Petroleum Jan. ’59 Linear programming. Sales analysis Co. Ltd., London. 11 Royal Aircraft Establishment, Mar. ’59 Aircraft calculations - Farnborough. 12 ICI Ltd., Central Instruments Jun. ’59 Chemical process analysis - Division, Reading. 13 Swedish Atomic Energy Jul. ’59 Atomic energy work - Authority, Stockholm. 14 Belgian Atomic Energy Sept. ’59 Atomic energy work - Authority, Mol. 15 The General Electric Co. Ltd., Dec. ’59 Atomic energy work - Erith. and machine design. 16 Metropolitan-Vickers Electrical Oct. ’60 Transformer design - Co. -

A Large Routine

A large routine Freek Wiedijk It is not widely known, but already in June 1949∗ Alan Turing had the main concepts that still are the basis for the best approach to program verification known today (and for which Tony Hoare developed a logic in 1969). In his three page paper Checking a large routine, Turing describes how to verify the correctness of a program that calculates the factorial function by repeated additions. He both shows how to use invariants to establish the correctness of this program, as well as how to use a variant to establish termination. In the paper the program is only presented as a flow chart. A modern C rendering is: int fac (int n) { int s, r, u, v; for (u = r = 1; v = u, r < n; r++) for (s = 1; u += v, s++ < r; ) ; return u; } Turing's paper seems not to have been properly appreciated at the time. At the EDSAC conference where Turing presented the paper, Douglas Hartree criticized that the correctness proof sketched by Turing should not be called inductive. From a modern point of view this is clearly absurd. Marc Schoolderman first told me about this paper (and in his master's thesis used the modern Why3 tool of Jean-Christophe Filli^atreto make Turing's paper fully precise; he also wrote the above C version of Turing's program). He then challenged me to speculate what specific computer Turing had in mind in the paper, and what the actual program for that computer might have been. My answer is that the `EPICAC'y of this paper probably was the Manchester Mark 1. -

Systems Architecture of the Ferranti Mark I and Mark I* Computers

Version 1, August 2011. CCS-F1X2 Systems Architecture of the Ferranti Mark I and Mark I* computers. Contents. 1. Historical development. 2. The early Manchester University computers, 1948 – 1949. 3. Overview of the Ferranti Mark I. 4. Summary of the main differences between the Ferranti Mark I and the Mark I*. 1. Historical development. These Ferranti machines were the fully-engineered production versions of prototype computers designed and built at the University of Manchester. The first of the prototypes was called the Small Scale Experimental Machine (SSEM), also known as the Baby. The SSEM first ran a program on the morning of Monday 21st June 1948, thereby being the world‟s first electronic stored-program computer to become operational. The SSEM was a minimal computer, primarily intended to test a novel storage system that had been developed by F C Williams and T Kilburn, first at the Telecommunications Research Establishment and then, from January 1947 at the Electro-technical Department of the University of Manchester where Professor Freddie Williams moved to become head of Department. Tom Kilburn was seconded to Manchester, to help with the storage research. The novel storage system, later to be called the Williams-Kilburn tube, depended upon regenerating a pattern of electrostatically- charged spots on the inner surface of a cathode ray tube. The system is thus sometimes called CRT storage, or electrostatic storage. Each charged spot represented a binary one or zero. Two varieties of spots were tried: dot-dash, and focus-defocus, the latter being used on the Ferranti computers. The system was patented and eventually used under licence on several early computers, including the IBM 701 and 702. -

Università Degli Studi Di Padova Padua Research Archive

Università degli Studi di Padova Padua Research Archive - Institutional Repository Seventy Years of Getting Transistorized Original Citation: Availability: This version is available at: 11577/3257397 since: 2018-02-15T16:02:20Z Publisher: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. Published version: DOI: 10.1109/MIE.2017.2757775 Terms of use: Open Access This article is made available under terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Guidelines, as described at http://www.unipd.it/download/file/fid/55401 (Italian only) (Article begins on next page) Historical by Massimo Guarnieri Seventy Years of Getting Transistorized Massimo Guarnieri acuum tubes appeared at the germanium. His device resembled the War II. Ohl, an American researcher break of the 20th century, giv- previous work of Julius Edgar Lilienfeld at Bell Labs, had invented the doping Ving birth to electronics [1]. By the (1882–1963) and Russell Shoemaker technique and produced the first p–n 1930s, they had become established as a Ohl (1898–1987) [5]. Lilienfeld was a junction in 1939. The patent applica- mature technology, spreading into areas German physicist who had migrated to tion for the transistor was submitted such as radio communications, long- the United States in 1921, where he had in June 1948. Although Shockley led distance radiotelegraphy, radio broad- patented a field-effect-transistor-like the team of Bardeen and Brattain at the casting, telephone communication and device in 1925. However, he had been Solid-State Physics Group, they devel- switching, sound recording and play- unable to make a working prototype be- oped their two devices independently ing, television, radar, and air navigation cause of a lack of sufficiently pure crys- because of the strong antagonism be- [2]. -

Tom Kilburn (1921–2001) Determined to See Projects Through to Completion

news and views Obituary scientists at this time, his wartime experience in radar made him Tom Kilburn (1921–2001) determined to see projects through to completion. Kilburn’s enthusiasm for By 1947 the theory of general-purpose, implementation became the hallmark of stored-program computers was familiar to computer science at Manchester. Kilburn several research groups on both sides of was accorded the scientific accolade of the Atlantic. However, the lack of suitable fellowship of the Royal Society in 1965. high-speed memory devices stopped them Kilburn was a modest individual who turning theory into practice. To quote actively shunned publicity. In 1968 he was Nathaniel Rochester of IBM, writing in the asked why computer science textbooks premier US electronics journal (Proc. IRE, seldom mentioned the early pioneering p. 374; April 1950): “The most difficult work at Manchester. Kilburn paused, and problem in the construction of large-scale then replied mysteriously: “Because those digital computers continues to be the who need to know, do know.” Such question of how to build a memory, and isolationism was sometimes the despair of MANCHESTER DEPT COMPUTER SCIENCE, UNIV. the few papers written do not reflect the his more gregarious colleagues, but greatness of the effort which is being Kilburn’s ability to remain focused on a exerted.” It was in this context that Tom problem enabled him to lead his team Kilburn began working for his PhD at the from the front. University of Manchester. His task was to In a field of scientific endeavour perfect a new form of digital memory. characterized by transitory, ad hoc The starting point was an observation by developments, it is not easy to explain F. -

Ferranti Mark I and Mark I*: List of References

F1X5 Version 3, 04/11/ 2018. Ferranti Mark I and Mark I*: list of references. The background to all the early British stored-program projects from 1945 – 1951 is summarised in: Alan Turing and his Contemporaries: building the world’s first computers . Simon Lavington [ed]. Published by BCS in 2012. 111 pages; many illustrations. ISBN: 978-1-90612-490-8. Another general account, spanning the period from the late 1940s to the mid-1960s, is: Early British Computers (Simon Lavington). Published by Manchester University Press (in the UK) and Digital Press (in the USA) in 1980. 139 pages, many illustrations. ISBN: 0- 7190-0803-4. Available online at: http://ed-thelen.org/comp-hist/EarlyBritish.html Recent research into the Ferranti Mark I and Mark I* is covered in: Stardust: tales from the early days of computing, 1948 – 1958. Simon Lavington. Book in preparation, November 2018. Ferranti Mark I: Hardware and systems architecture. Original papers. 1. Williams, F C and Kilburn, T, A storage system for use with binary-digital computing machines. Proc. IEE, vol. 96, part 2, no. 30, 1949, pages 183 ff. 2. Williams, F C, Kilburn, T and Tootill, G C, Universal high-speed digital computers: a small-scale experimental machine. Proc. IEE, vol. 98, part 2, no. 61, Feb. 1951, pages 13 – 28. 3. Kilburn, T, The University of Manchester universal high-speed digital computing machine. Nature, vol. 164, no. 4173, October 1949, page 684 – 687. 4. West, J C and Williams, F C, The position synchronisation of a rotating drum. Proc. IEE, vol. 98, part 2, no. -

Lean, Tom. "Electronic Brains." Electronic Dreams: How 1980S Britain Learned to Love the Computer. London: Bloomsbury Sigma, 2016

Lean, Tom. "Electronic Brains." Electronic Dreams: How 1980s Britain Learned to Love the Computer. London: Bloomsbury Sigma, 2016. 9–33. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 28 Sep. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472936653.0004>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 28 September 2021, 05:11 UTC. Copyright © Tom Lean 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. CHAPTER ONE Electronic Brains n June 1948, in a drab laboratory in the Gothic surroundings Iof the Victoria University of Manchester, a small team of electronics engineers observed the success of an experiment they had been working on for months. The object of their interest was an untidy mass of electronics that fi lled the tall, bookcase-like racks lining the walls of the room. At the centre of this bird ’ s nest of cables, radio valves and other components glowed a small, round display screen that allowed a glimpse into the machine ’ s electronic memory, a novel device sitting off to one side hidden in a metal box. This hotchpotch assembly of electronic bits and bobs was offi cially known as the Small- Scale Experimental Machine (SSEM), but has become better known as the ‘ Manchester Baby ’ . It was the world ’ s fi rst electronic stored program computer, a computer that used an electronic memory to store data and the program that instructed it what to do, the basic architecture still used by most computers today. Baby ’ s creators, Tom Kilburn, Geoff rey Tootill and Freddy Williams, were all electronics engineers seasoned by years of work developing wartime radar systems under great secrecy and urgency. -

TURING and the PRIMES Alan Turing's Exploits in Code Breaking, Philosophy, Artificial Intelligence and the Founda- Tions of Co

TURING AND THE PRIMES ANDREW R. BOOKER Alan Turing's exploits in code breaking, philosophy, artificial intelligence and the founda- tions of computer science are by now well known to many. Less well known is that Turing was also interested in number theory, in particular the distribution of prime numbers and the Riemann Hypothesis. These interests culminated in two programs that he implemented on the Manchester Mark 1, the first stored-program digital computer, during its 18 months of operation in 1949{50. Turing's efforts in this area were modest,1 and one should be careful not to overstate their influence. However, one cannot help but see in these investigations the beginning of the field of computational number theory, bearing a close resemblance to active problems in the field today, despite a gap of 60 years. We can also perceive, in hind- sight, some striking connections to Turing's other areas of interests, in ways that might have seemed far fetched in his day. This chapter will attempt to explain the two problems in detail, including their early history, Turing's contributions, some of the developments since the 1950s, and speculation for the future. A bit of history Turing's plans for a computer. Soon after his involvement in the war effort ended, Turing set about plans for a general-purpose digital computer. He submitted a detailed design for the Automatic Computing Engine (ACE) to the National Physics Laboratory in early 1946. Turing's design drew on both his theoretical work \On Computable Numbers" from a decade earlier, and the practical knowledge gained during the war from working at Bletchley Park, where the Colossus machines were developed and used.