De Stella Nova

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hints Into Kepler's Method

Stefano Gattei [email protected] Hints into Kepler’s method ABSTRACT The Italian Academy, Columbia University February 4, 2009 Some of Johannes Kepler’s works seem very different in character. His youthful Mysterium cosmographicum (1596) argues for heliocentrism on the basis of metaphysical, astronomical, astrological, numerological, and architectonic principles. By contrast, Astronomia nova (1609) is far more tightly argued on the basis of only a few dynamical principles. In the eyes of many, such a contrast embodies a transition from Renaissance to early modern science. However, Kepler did not subsequently abandon the broader approach of his early works: similar metaphysical arguments reappeared in Harmonices mundi libri V (1619), and he reissued the Mysterium cosmographicum in a second edition in 1621, in which he qualified only some of his youthful arguments. I claim that the conceptual and stylistic features of the Astronomia nova – as well as of other “minor” works, such as Strena seu De nive sexangula (1611) or Nova stereometria doliorum vinariorum (1615) – are intimately related and were purposely chosen because of the response he knew to expect from the astronomical community to the revolutionary changes in astronomy he was proposing. Far from being a stream-of-consciousness or merely rhetorical kind of narrative, as many scholars have argued, Kepler’s expository method was carefully calculated both to convince his readers and to engage them in a critical discussion in the joint effort to know God’s design. By abandoning the perspective of the inductivist philosophy of science, which is forced by its own standards to portray Kepler as a “sleepwalker,” I argue that the key lies in the examination of Kepler’s method: whether considering the functioning and structure of the heavens or the tiny geometry of the little snowflakes, he never hesitated to discuss his own intellectual journey, offering a rational reconstruction of the series of false starts, blind alleys, and failures he encountered. -

Borromini and the Cultural Context of Kepler's Harmonices Mundi

Borromini and the Dr Valerie Shrimplin cultural context of [email protected] Kepler’sHarmonices om Mundi • • • • Francesco Borromini, S Carlo alle Quattro Fontane Rome (dome) Harmonices Mundi, Bk II, p. 64 Facsimile, Carnegie-Mellon University Francesco Borromini, S Ivo alla Sapienza Rome (dome) Harmonices Mundi, Bk IV, p. 137 • Vitruvius • Scriptures – cosmology and The Genesis, Isaiah, Psalms) cosmological • Early Christian - dome of heaven view of the • Byzantine - domed architecture universe and • Renaissance revival – religious art/architecture symbolism of centrally planned churches • Baroque (17th century) non-circular domes as related to Kepler’s views* *INSAP II, Malta 1999 Cosmas Indicopleustes, Universe 6th cent Last Judgment 6th century (VatGr699) Celestial domes Monastery at Daphne (Δάφνη) 11th century S Sophia, Constantinople (built 532-37) ‘hanging architecture’ Galla Placidia, 425 St Mark’s Venice, late 11th century Evidence of Michelangelo interests in Art and Cosmology (Last Judgment); Music/proportion and Mathematics Giacomo Vignola (1507-73) St Andrea in Via Flaminia 1550-1553 Church of San Giacomo in Augusta, in Rome, Italy, completed by Carlo Maderno 1600 [painting is 19th century] Sant'Anna dei Palafrenieri, 1620’s (Borromini with Maderno) Leonardo da Vinci, Notebooks (318r Codex Atlanticus c 1510) Amboise Bachot, 1598 Following p. 52 Astronomia Nova Link between architecture and cosmology (as above) Ovals used as standard ellipse approximation Significant change/increase Revival of neoplatonic terms, geometrical bases in early 17th (ellipse, oval, equilateral triangle) century Fundamental in Harmonices Mundi where orbit of every planet is ellipse with sun at one of foci Borromini combined practical skills with scientific learning and culture • Formative years in Milan (stonemason) • ‘Artistic anarchist’ – innovation and disorder. -

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630)

EDUB 1760/PHYS 2700 II. The Scientific Revolution Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) The War on Mars Cameron & Stinner A little background history Where: Holy Roman Empire When: The thirty years war Why: Catholics vs Protestants Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 2 A little background history Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 3 The short biography • Johannes Kepler was born in Weil der Stadt, Germany, in 1571. He was a sickly child and his parents were poor. A scholarship allowed him to enter the University of Tübingen. • There he was introduced to the ideas of Copernicus by Maestlin. He first studied to become a priest in Poland but moved Tübingen Graz to Graz, Austria to teach school in 1596. • As mathematics teacher in Graz, Austria, he wrote the first outspoken defense of the Copernican system, the Mysterium Cosmographicum. Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 4 Mysterium Cosmographicum (1596) Kepler's Platonic solids model of the Solar system. He sent a copy . to Tycho Brahe who needed a theoretician… Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 5 The short biography Kepler was forced to leave his teaching post at Graz and he moved to Prague to work with the renowned Danish Prague astronomer, Tycho Brahe. Graz He inherited Tycho's post as Imperial Mathematician when Tycho died in 1601. Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 6 The short biography Using the precise data (~1’) that Tycho had collected, Kepler discovered that the orbit of Mars was an ellipse. In 1609 he published Astronomia Nova, presenting his discoveries, which are now called Kepler's first two laws of planetary motion. Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 7 Tycho Brahe The Aristocrat The Observer Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 8 Tycho Brahe - the Observer The Great Comet of 1577 -from Brahe’s notebooks Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 9 Tycho Brahe’s Cosmology …was a modified heliocentric one Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 10 The short biography • In 1612 Lutherans were forced out of Prague, so Kepler moved on to Linz, Austria. -

Astrology, Mechanism and the Soul by Patrick J

Kepler’s Cosmological Synthesis: Astrology, Mechanism and the Soul by Patrick J. Boner History of Science and Medicine Library 39/Medieval and Early Modern Sci- ence 20. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2013. Pp. ISBN 978–90–04–24608–9. Cloth $138.00 xiv + 187 Reviewed by André Goddu Stonehill College [email protected] Johannes Kepler has always been something of a puzzle if not a scandal for historians of science. Even when historians acknowledged Renaissance, magical, mystical, Neoplatonic/Pythagorean influences, they dismissed or minimized them as due to youthful exuberance later corrected by rigorous empiricism and self-criticism.The pressure to see Kepler as a mathematical physicist and precursor to Newton’s synthesis remains seductive because it provides such a neat and relatively simple narrative. As a result, the image of Kepler as a mechanistic thinker who helped to demolish the Aristotelian world view has prevailed—and this despite persuasive characterization of Kepler as a transitional figure, the culmination of one tradition and the beginning of another by David Lindberg [1986] in referring to Kepler’s work on optics and by Bruce Stephenson [1987, 1–7] in discussing Kepler on physical astronomy. In this brief study, Patrick Boner once again challenges the image of Kepler as a reductivist, mechanistic thinker by summarizing and quoting passages of works and correspondence covering many of Kepler’s ideas, both early and late, that confirm how integral Kepler’s animistic beliefs were with his understanding of natural, physical processes. Among Boner’s targets, Anneliese Maier [1937], Eduard Dijksterhuis [1961], Reiner Hooykaas [1987], David Keller and E. -

Orbital Mechanics Joe Spier, K6WAO – AMSAT Director for Education ARRL 100Th Centennial Educational Forum 1 History

Orbital Mechanics Joe Spier, K6WAO – AMSAT Director for Education ARRL 100th Centennial Educational Forum 1 History Astrology » Pseudoscience based on several systems of divination based on the premise that there is a relationship between astronomical phenomena and events in the human world. » Many cultures have attached importance to astronomical events, and the Indians, Chinese, and Mayans developed elaborate systems for predicting terrestrial events from celestial observations. » In the West, astrology most often consists of a system of horoscopes purporting to explain aspects of a person's personality and predict future events in their life based on the positions of the sun, moon, and other celestial objects at the time of their birth. » The majority of professional astrologers rely on such systems. 2 History Astronomy » Astronomy is a natural science which is the study of celestial objects (such as stars, galaxies, planets, moons, and nebulae), the physics, chemistry, and evolution of such objects, and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth, including supernovae explosions, gamma ray bursts, and cosmic microwave background radiation. » Astronomy is one of the oldest sciences. » Prehistoric cultures have left astronomical artifacts such as the Egyptian monuments and Nubian monuments, and early civilizations such as the Babylonians, Greeks, Chinese, Indians, Iranians and Maya performed methodical observations of the night sky. » The invention of the telescope was required before astronomy was able to develop into a modern science. » Historically, astronomy has included disciplines as diverse as astrometry, celestial navigation, observational astronomy and the making of calendars, but professional astronomy is nowadays often considered to be synonymous with astrophysics. -

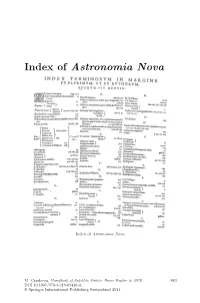

Index of Astronomia Nova

Index of Astronomia Nova Index of Astronomia Nova. M. Capderou, Handbook of Satellite Orbits: From Kepler to GPS, 883 DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-03416-4, © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 Bibliography Books are classified in sections according to the main themes covered in this work, and arranged chronologically within each section. General Mechanics and Geodesy 1. H. Goldstein. Classical Mechanics, Addison-Wesley, Cambridge, Mass., 1956 2. L. Landau & E. Lifchitz. Mechanics (Course of Theoretical Physics),Vol.1, Mir, Moscow, 1966, Butterworth–Heinemann 3rd edn., 1976 3. W.M. Kaula. Theory of Satellite Geodesy, Blaisdell Publ., Waltham, Mass., 1966 4. J.-J. Levallois. G´eod´esie g´en´erale, Vols. 1, 2, 3, Eyrolles, Paris, 1969, 1970 5. J.-J. Levallois & J. Kovalevsky. G´eod´esie g´en´erale,Vol.4:G´eod´esie spatiale, Eyrolles, Paris, 1970 6. G. Bomford. Geodesy, 4th edn., Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1980 7. J.-C. Husson, A. Cazenave, J.-F. Minster (Eds.). Internal Geophysics and Space, CNES/Cepadues-Editions, Toulouse, 1985 8. V.I. Arnold. Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, Graduate Texts in Mathematics (60), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1989 9. W. Torge. Geodesy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1991 10. G. Seeber. Satellite Geodesy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1993 11. E.W. Grafarend, F.W. Krumm, V.S. Schwarze (Eds.). Geodesy: The Challenge of the 3rd Millennium, Springer, Berlin, 2003 12. H. Stephani. Relativity: An Introduction to Special and General Relativity,Cam- bridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004 13. G. Schubert (Ed.). Treatise on Geodephysics,Vol.3:Geodesy, Elsevier, Oxford, 2007 14. D.D. McCarthy, P.K. -

Exam Example Questions

Question 11. Distance to the galaxies who was the first to determine the distances to an external galaxy: Galilei Galileo Vesto Slipher Edwin Hubble Knut Lundmark Question 12. Henriette Leavitt what was the instrumental contribution by Henrietta Leavitt ? the distance to extragalactic nebulae the period-luminosity relation of Cepheids the colour-luminosity relation of Cepheids the period-luminosity relation of RR Lyrae stars Question 13. Aristoteleian cosmology Aristotle suggested that the reason for anything coming about can be at- tributed to four different types of active causal factors. Which of the follow- ing is NOT one of these ? efficient cause original cause material cause formal cause Question 14. Tycho Brahe & Uraniborg Where did Tycho Brahe build his famous observatory Uraniborg ? Hvend Prague Regensburg Copenhagen Question 15. Tycho Brahe and the Solar System which model of the solar system did Tycho Brahe support: Ptolemaic/geocentric heliocentric/Copernican geo-heliocentric Keplerian cont'd next page 4 Question 46. Kepler's Laws and Mars In which two great publications did Kepler describe his struggle with Mars, leading him to the three laws of Kepler ? Mysterium cosmographicum & Dialogo Harmonices mundi & Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematicae Astronomia nova & Epitome astronomiae copernicanae Dioptrica & Mysterium cosmographicum Question 47. Hubble and extragalactic distances of which galaxy did Edwin Hubble manage to determine for the first time the distance, and what was his estimate ? the Large Magellanic Cloud, 150,000 lightyears the Andromeda Galaxy/M31, 1 million lightyears the Small Magellanic cloud, 30,000 lightyears the Large Magellanic Cloud, 1 million lightyears Question 48. De Stella Nova Why is the publication of De Stella Nova (1572) by Tycho Brahe devastating for the Aristoteleian cosmological views ? Tycho's observations were so accurate that they proved Aristotle's pre- dictions wrong. -

The Harmony of the Spheres from Pythagoras to Voyager

The Role of Astronomy in Society and Culture Proceedings IAU Symposium No. 260, 2009 c International Astronomical Union 2011 D. Valls-Gabaud & A. Boksenberg, eds. doi:10.1017/S1743921311002535 The Harmony of the Spheres from Pythagoras to Voyager Dominique Proust Observatoire de Paris 92195 Meudon, 5 Place Jules Janssen, France email: [email protected] Abstract. We present the strong links between music and astronomy over 25 centuries. Keywords. Astronomy, Music 1. Introduction Astronomy is probably the most ancient of all the sciences, the celestial vault having attracted mans attention from very early on as much by its sumptuous beauty as by its mystery. Every day, the sun rose and set, the phases of the moon came in succession, and the same stars reappeared periodically. The persistence of these movements is at the origin of the laws on which were based those civilizations that followed the rhythm of the sky. We have to wait until the 6th century BCE for these first theories about observation to develop by associating celestial mechanics with music. The Ionians looked progressively at isolating natural phenomena in order to interpret them. For example, they noticed the tidal movement of the sea; they also knew the phases and movement of the moon. Was there a link between these phenomena? On the other hand, they tried to explain sonar phenomena such as resonance, echo, or the sounds produced by musical instruments such as flutes, strings and percussion. Did they believe the world was ruled by a unitary theory? From his research came the idea of the Harmony of the Spheres. -

The Order of Things: Hierarchies, Structures and Pecking Orders for the Voraciously Curious Free

FREE THE ORDER OF THINGS: HIERARCHIES, STRUCTURES AND PECKING ORDERS FOR THE VORACIOUSLY CURIOUS PDF Barbara Ann Kipfer | 720 pages | 06 Dec 2008 | Workman Publishing | 9780761150442 | English | New York, United States Rome, of The Three Cities, by Emile Zola English Pages Year Internet of Things: Principles and Paradigms captures the state-of-the-art research in Internet of Things, its applicati. As one of the contestants in the first official World Championship match inJohannes Hermann Zukertort What's the best way to stretch watercolor paper? What basic materials do I need to start oil painting? How can I Structures and Pecking Orders for the Voraciously Curious. From the moment she first learned to read, literary genius Darcy Wells has spent most of her time living in the worlds o. Table of contents : Preface Page 6 Contents Page 7 1 Introduction Page 10 This Book Page 12 Esthetics Page 16 Homeostasis Page 17 Gestalt Page 18 Mythology Page 19 Communication Page 20 Power Page 22 Peers Page 25 The Holy Roman Empire Page 27 World View Page 31 Weil der Stadt Page 32 Further Education Page 34 Pythagoras Page 35 Maestlin Page 36 Nicolas Cusanus Page 37 Leaving Tubingen Page 38 5 Graz Page The Order of Things: Hierarchies Prognostica Page 42 Euclid Page 43 Mysterium Cosmographicum Page 45 Galileo Galilei [16] Page 47 Tycho Brahe Page 56 Mars Page 58 Prague Page 59 Force Page 61 Gravitation Page 62 Astronomia Nova Page 63 Telescopes Page 69 Truth Page 70 Linz Page 71 Bernegger Page 73 The Heretic Page 74 Credo Page 78 Witch Hunt Page 79 Harmonices Mundi Page 85 Tabulae Rudolphinae Page 87 Wallenstein Page 90 Astrology Page 95 Sagan Page 96 Regensburg Page 99 Newton Page Max Planck Page Albert Einstein Page Deconstruction Page Riddles Page Rebuilding Harmony Page 11 Conclusions Page John Nash Page Timeline Page References Page Name Index Page Subject Index Page Autobiographies and memoirs also fall into the scope of the series. -

Music of the Spheres

Music of the Spheres Parvathi Nayar There's not the smallest orb which thou behold'st But in his motion like an angel sings, Still quiring to the young-eyed cherubins; Such harmony is in immortal souls; But whilst this muddy vesture of decay Doth grossly close it in, we cannot hear it. (Shakespeare, Merchant of Venice) Introduction to the artwork, Music of the Spheres Long ago, when the heavens were imagined as a more orderly place, mathematicians, musicians and philosophers saw relationships between mathematics, the movements of celestial bodies, and the harmonies of music. Rather more recently, in the field of astro-seismology, scientists \listen" to the stars, and make studies of their inner structures, via the sound waves that are bouncing around within them. Responding playfully and thoughtfully to such twinning of the celestial and the earthly, is Music of the Spheres, a 30-foot long art installation by Parvathi Nayar. She has created the artwork as a response to the new CMI space; i.e., the artist views this auditorium within a mathematical institute as a unique architectural combination of the arts and the sciences. Music of The Spheres is a celebration and extension of the venue's purpose|to hold learned symposiums and convocations as well as a range of performance arts from music to theatre|that is expressed through the multi-layered language of Parvathi's drawings, The artwork owes much to Pythagoras' worldview of the Sun, Moon and other planets resonating to a beautiful noise inaudible to our human ears|as well as to the newest discoveries of colliding black holes sending out ripples through space. -

Johann Keplers Beziehungen Zu Regensburg

Johann Keplers Beziehungen zu Regensburg. Benützte Werke und Quellen (außer den im Text angegebenen): Ch. Frifch: Joh. Kepleri opera omnia, Frankfurt/M. 1858—1870. L. Schuft er: Joh. Kepler und die kirchlichen Streitfragen. Graz 1888. W. v. D y ck u. M. C a f p a r : Die Keplerbriefe auf der Nat.-Bibl. und auf der Sternwarte in Paris. München 1927. Abh. d. b. Akad. d. W. v. Breitfehwert: Keplers Leben und Wirken. Stuttgart 1831. Gumpelzhaimer : Regensburgs Gefchichte. Reitlinger, Neumann, Gruner: Joh. Kepler. Stuttgart 1868. Anonym: Johannes Kepler. Wien, Peft, Leipzig 1871. C. Gruner: Keplers wahrer Geburtsort. Stuttgart 1866. C. W. Neumann: Das Wohn- und das wahre Sterbehaus Keplers in Regens• burg. Regensburg 1864/65. F. O h m a n n : Die Anfänge des Poftwefens. Leipzig 1909. R. Freytag: Zur Poftgefchichte von Augsburg, Nürnberg und Regensburg. Arch. f. Poftgefch. i. Bay. 1929/1. J. Ph. Oftertag: Keplers Monument in Regensburg. 1786. Manufkr. ^ der Kreisbibliothek und des Hiftorifchen Vereins Regensburg. Archivalieh, Siegelprotokolle, Beifitzerbücher im Stadtarchiv zu Regensburg. Kirchenbücher des evangelifchen Pfarramts unterer Stadt in Regensburg. /. Gefchichtlicbes Von Adolf Schmetzer, Oberbaurat a. D. Regensburg Einleitung. Um Keplers Beziehungen zu Regensburg darzuftellen, die in feinem vielbewegten Leben eine große Rolle gefpielt haben, reicht unmöglich eine abfehnittweife Aufzählung aus, wie oft und wie lange er und die Seinen hier weilten, wo fie gewohnt, was fie hier gewirkt und an Freud und Leid erfahren haben. Vielmehr muffen diefe Erhebungen zur Aufzeichnung eines in Urfache und Wirkung geklärten Gefamtbildes in Zufammenhang gebracht werden mit Keplers ganzem Lebensgang und feiner Perfönlichkeit, fowie mit den gleichzeitigen politifchen Gefchehniffen und religiöfen Span• nungen, wenn auch diefe Bindeglieder hier mehr und weniger nur in Um- rillen gefchildert werden. -

Celestial Mechanics: from Antiquity to Modern Times - Alessandra Celletti

CELESTIAL MECHANICS - Celestial Mechanics: From Antiquity to Modern Times - Alessandra Celletti CELESTIAL MECHANICS: FROM ANTIQUITY TO MODERN TIMES Alessandra Celletti Dipartimento di Matematica, Università di Roma Tor Vergata, Italy Keywords: Epicycles, deferents, Kepler’s laws, Hohmann transfer, sphere of influence, gravity assist, nearly–integrable system, action–angle variables, perturbation theory, small divisor, resonance, KAM theory, invariant torus, Nekhoroshev’s theorem, spin– orbit model, 3–body problem, planetary problem, Lagrangian points. Contents 1. Introduction 2. From Ptolemy to Copernicus 3. Kepler's Laws and Hohmann Transfers 4. The 3—Body Problem and Gravity Assist 5. Perturbation Theory and the Perihelion of Mercury 6. KAM and Nekhoroshev's Theories in Celestial Mechanics Glossary Bibliography Biographical Sketch Summary Celestial Mechanics has followed the development of humankind from antiquity to space exploration age. After a short review of the cosmological models dating back to ancient Greeks, we proceed to present the main achievements which led to modern Celestial Mechanics. First, we describe Kepler’s laws which explain how planets move around the Sun, thanks to Newton’s gravitational force. Despite the fact that they were discovered in the XVII century, these laws provide interesting tools for managing a spacecraft trajectory, like the so–called Hohmann transfers and the gravity assist technique. Then we present perturbation theory developed in the XVIII century, which is an extremely important tool in Celestial Mechanics: for example, it led to the discovery of Neptune, to the computation of the perihelion’s precession as well as to accurate lunar ephemerides. Stability results can be obtained thanks to the outstanding theories developed in the XX century by Kolmogorov, Arnold, Moser (KAM theory) and Nekhoroshev, that we shortly present, together with some of their applications to Celestial Mechanics.