Orbit Mechanics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hints Into Kepler's Method

Stefano Gattei [email protected] Hints into Kepler’s method ABSTRACT The Italian Academy, Columbia University February 4, 2009 Some of Johannes Kepler’s works seem very different in character. His youthful Mysterium cosmographicum (1596) argues for heliocentrism on the basis of metaphysical, astronomical, astrological, numerological, and architectonic principles. By contrast, Astronomia nova (1609) is far more tightly argued on the basis of only a few dynamical principles. In the eyes of many, such a contrast embodies a transition from Renaissance to early modern science. However, Kepler did not subsequently abandon the broader approach of his early works: similar metaphysical arguments reappeared in Harmonices mundi libri V (1619), and he reissued the Mysterium cosmographicum in a second edition in 1621, in which he qualified only some of his youthful arguments. I claim that the conceptual and stylistic features of the Astronomia nova – as well as of other “minor” works, such as Strena seu De nive sexangula (1611) or Nova stereometria doliorum vinariorum (1615) – are intimately related and were purposely chosen because of the response he knew to expect from the astronomical community to the revolutionary changes in astronomy he was proposing. Far from being a stream-of-consciousness or merely rhetorical kind of narrative, as many scholars have argued, Kepler’s expository method was carefully calculated both to convince his readers and to engage them in a critical discussion in the joint effort to know God’s design. By abandoning the perspective of the inductivist philosophy of science, which is forced by its own standards to portray Kepler as a “sleepwalker,” I argue that the key lies in the examination of Kepler’s method: whether considering the functioning and structure of the heavens or the tiny geometry of the little snowflakes, he never hesitated to discuss his own intellectual journey, offering a rational reconstruction of the series of false starts, blind alleys, and failures he encountered. -

Instructor's Guide for Virtual Astronomy Laboratories

Instructor’s Guide for Virtual Astronomy Laboratories Mike Guidry, University of Tennessee Kevin Lee, University of Nebraska The Brooks/Cole product Virtual Astronomy Laboratories consists of 20 virtual online astronomy laboratories (VLabs) representing a sampling of interactive exercises that illustrate some of the most important topics in introductory astronomy. The exercises are meant to be representative, not exhaustive, since introductory astronomy is too broad to be covered in only 20 laboratories. Material is approximately evenly divided between that commonly found in the Solar System part of an introductory course and that commonly associated with the stars, galaxies, and cosmology part of such a course. Intended Use This material was designed to serve two general functions: on the one hand it represents a set of virtual laboratories that can be used as part or all of an introductory astronomy laboratory sequence, either within a normal laboratory setting or in a distance learning environment. On the other hand, it is meant to serve as a tutorial supplement for standard textbooks. While this is an efficient use of the material, it presents some problems in organization since (as a rule of thumb) supplemental tutorial material is more concept oriented while astronomy laboratory material typically requires more hands-on problem-solving involving at least some basic mathematical manipulations. As a result, one will find material of varying levels of difficulty in these laboratories. Some sections are highly conceptual in nature, emphasizing more qualitative answers to questions that students may deduce without working through involved tasks. Other sections, even within the same virtual laboratory, may require students to carry out guided but non-trivial analysis in order to answer questions. -

The Search for Exomoons and the Characterization of Exoplanet Atmospheres

Corso di Laurea Specialistica in Astronomia e Astrofisica The search for exomoons and the characterization of exoplanet atmospheres Relatore interno : dott. Alessandro Melchiorri Relatore esterno : dott.ssa Giovanna Tinetti Candidato: Giammarco Campanella Anno Accademico 2008/2009 The search for exomoons and the characterization of exoplanet atmospheres Giammarco Campanella Dipartimento di Fisica Università degli studi di Roma “La Sapienza” Associate at Department of Physics & Astronomy University College London A thesis submitted for the MSc Degree in Astronomy and Astrophysics September 4th, 2009 Università degli Studi di Roma ―La Sapienza‖ Abstract THE SEARCH FOR EXOMOONS AND THE CHARACTERIZATION OF EXOPLANET ATMOSPHERES by Giammarco Campanella Since planets were first discovered outside our own Solar System in 1992 (around a pulsar) and in 1995 (around a main sequence star), extrasolar planet studies have become one of the most dynamic research fields in astronomy. Our knowledge of extrasolar planets has grown exponentially, from our understanding of their formation and evolution to the development of different methods to detect them. Now that more than 370 exoplanets have been discovered, focus has moved from finding planets to characterise these alien worlds. As well as detecting the atmospheres of these exoplanets, part of the characterisation process undoubtedly involves the search for extrasolar moons. The structure of the thesis is as follows. In Chapter 1 an historical background is provided and some general aspects about ongoing situation in the research field of extrasolar planets are shown. In Chapter 2, various detection techniques such as radial velocity, microlensing, astrometry, circumstellar disks, pulsar timing and magnetospheric emission are described. A special emphasis is given to the transit photometry technique and to the two already operational transit space missions, CoRoT and Kepler. -

TOPICS in CELESTIAL MECHANICS 1. the Newtonian N-Body Problem

TOPICS IN CELESTIAL MECHANICS RICHARD MOECKEL 1. The Newtonian n-body Problem Celestial mechanics can be defined as the study of the solution of Newton's differ- ential equations formulated by Isaac Newton in 1686 in his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica. The setting for celestial mechanics is three-dimensional space: 3 R = fq = (x; y; z): x; y; z 2 Rg with the Euclidean norm: p jqj = x2 + y2 + z2: A point particle is characterized by a position q 2 R3 and a mass m 2 R+. A motion of such a particle is described by a curve q(t) where t runs over some interval in R; the mass is assumed to be constant. Some remarks will be made below about why it is reasonable to model a celestial body by a point particle. For every motion of a point particle one can define: velocity: v(t) =q _(t) momentum: p(t) = mv(t): Newton formulated the following laws of motion: Lex.I. Corpus omne perservare in statu suo quiescendi vel movendi uniformiter in directum, nisi quatenus a viribus impressis cogitur statum illum mutare 1 Lex.II. Mutationem motus proportionem esse vi motrici impressae et fieri secundem lineam qua vis illa imprimitur. 2 Lex.III Actioni contrarium semper et aequalem esse reactionem: sive corporum duorum actiones in se mutuo semper esse aequales et in partes contrarias dirigi. 3 The first law is statement of the principle of inertia. The second law asserts the existence of a force function F : R4 ! R3 such that: p_ = F (q; t) or mq¨ = F (q; t): In celestial mechanics, the dependence of F (q; t) on t is usually indirect; the force on one body depends on the positions of the other massive bodies which in turn depend on t. -

Borromini and the Cultural Context of Kepler's Harmonices Mundi

Borromini and the Dr Valerie Shrimplin cultural context of [email protected] Kepler’sHarmonices om Mundi • • • • Francesco Borromini, S Carlo alle Quattro Fontane Rome (dome) Harmonices Mundi, Bk II, p. 64 Facsimile, Carnegie-Mellon University Francesco Borromini, S Ivo alla Sapienza Rome (dome) Harmonices Mundi, Bk IV, p. 137 • Vitruvius • Scriptures – cosmology and The Genesis, Isaiah, Psalms) cosmological • Early Christian - dome of heaven view of the • Byzantine - domed architecture universe and • Renaissance revival – religious art/architecture symbolism of centrally planned churches • Baroque (17th century) non-circular domes as related to Kepler’s views* *INSAP II, Malta 1999 Cosmas Indicopleustes, Universe 6th cent Last Judgment 6th century (VatGr699) Celestial domes Monastery at Daphne (Δάφνη) 11th century S Sophia, Constantinople (built 532-37) ‘hanging architecture’ Galla Placidia, 425 St Mark’s Venice, late 11th century Evidence of Michelangelo interests in Art and Cosmology (Last Judgment); Music/proportion and Mathematics Giacomo Vignola (1507-73) St Andrea in Via Flaminia 1550-1553 Church of San Giacomo in Augusta, in Rome, Italy, completed by Carlo Maderno 1600 [painting is 19th century] Sant'Anna dei Palafrenieri, 1620’s (Borromini with Maderno) Leonardo da Vinci, Notebooks (318r Codex Atlanticus c 1510) Amboise Bachot, 1598 Following p. 52 Astronomia Nova Link between architecture and cosmology (as above) Ovals used as standard ellipse approximation Significant change/increase Revival of neoplatonic terms, geometrical bases in early 17th (ellipse, oval, equilateral triangle) century Fundamental in Harmonices Mundi where orbit of every planet is ellipse with sun at one of foci Borromini combined practical skills with scientific learning and culture • Formative years in Milan (stonemason) • ‘Artistic anarchist’ – innovation and disorder. -

Kepler Press

National Aeronautics and Space Administration PRESS KIT/FEBRUARY 2009 Kepler: NASA’s First Mission Capable of Finding Earth-Size Planets www.nasa.gov Media Contacts J.D. Harrington Policy/Program Management 202-358-5241 NASA Headquarters [email protected] Washington 202-262-7048 (cell) Michael Mewhinney Science 650-604-3937 NASA Ames Research Center [email protected] Moffett Field, Calif. 650-207-1323 (cell) Whitney Clavin Spacecraft/Project Management 818-354-4673 Jet Propulsion Laboratory [email protected] Pasadena, Calif. 818-458-9008 (cell) George Diller Launch Operations 321-867-2468 Kennedy Space Center, Fla. [email protected] 321-431-4908 (cell) Roz Brown Spacecraft 303-533-6059. Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. [email protected] Boulder, Colo. 720-581-3135 (cell) Mike Rein Delta II Launch Vehicle 321-730-5646 United Launch Alliance [email protected] Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Fla. 321-693-6250 (cell) Contents Media Services Information .......................................................................................................................... 5 Quick Facts ................................................................................................................................................... 7 NASA’s Search for Habitable Planets ............................................................................................................ 8 Scientific Goals and Objectives ................................................................................................................. -

Kepler's Laws of Planetary Motion

Kepler's laws of planetary motion In astronomy, Kepler's laws of planetary motion are three scientific laws describing the motion ofplanets around the Sun. 1. The orbit of a planet is an ellipse with the Sun at one of the twofoci . 2. A line segment joining a planet and the Sun sweeps out equal areas during equal intervals of time.[1] 3. The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit. Most planetary orbits are nearly circular, and careful observation and calculation are required in order to establish that they are not perfectly circular. Calculations of the orbit of Mars[2] indicated an elliptical orbit. From this, Johannes Kepler inferred that other bodies in the Solar System, including those farther away from the Sun, also have elliptical orbits. Kepler's work (published between 1609 and 1619) improved the heliocentric theory of Nicolaus Copernicus, explaining how the planets' speeds varied, and using elliptical orbits rather than circular orbits withepicycles .[3] Figure 1: Illustration of Kepler's three laws with two planetary orbits. Isaac Newton showed in 1687 that relationships like Kepler's would apply in the 1. The orbits are ellipses, with focal Solar System to a good approximation, as a consequence of his own laws of motion points F1 and F2 for the first planet and law of universal gravitation. and F1 and F3 for the second planet. The Sun is placed in focal pointF 1. 2. The two shaded sectors A1 and A2 Contents have the same surface area and the time for planet 1 to cover segmentA 1 Comparison to Copernicus is equal to the time to cover segment A . -

Johannes Kepler (1571-1630)

EDUB 1760/PHYS 2700 II. The Scientific Revolution Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) The War on Mars Cameron & Stinner A little background history Where: Holy Roman Empire When: The thirty years war Why: Catholics vs Protestants Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 2 A little background history Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 3 The short biography • Johannes Kepler was born in Weil der Stadt, Germany, in 1571. He was a sickly child and his parents were poor. A scholarship allowed him to enter the University of Tübingen. • There he was introduced to the ideas of Copernicus by Maestlin. He first studied to become a priest in Poland but moved Tübingen Graz to Graz, Austria to teach school in 1596. • As mathematics teacher in Graz, Austria, he wrote the first outspoken defense of the Copernican system, the Mysterium Cosmographicum. Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 4 Mysterium Cosmographicum (1596) Kepler's Platonic solids model of the Solar system. He sent a copy . to Tycho Brahe who needed a theoretician… Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 5 The short biography Kepler was forced to leave his teaching post at Graz and he moved to Prague to work with the renowned Danish Prague astronomer, Tycho Brahe. Graz He inherited Tycho's post as Imperial Mathematician when Tycho died in 1601. Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 6 The short biography Using the precise data (~1’) that Tycho had collected, Kepler discovered that the orbit of Mars was an ellipse. In 1609 he published Astronomia Nova, presenting his discoveries, which are now called Kepler's first two laws of planetary motion. Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 7 Tycho Brahe The Aristocrat The Observer Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 8 Tycho Brahe - the Observer The Great Comet of 1577 -from Brahe’s notebooks Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 9 Tycho Brahe’s Cosmology …was a modified heliocentric one Johannes Kepler cameron & stinner 10 The short biography • In 1612 Lutherans were forced out of Prague, so Kepler moved on to Linz, Austria. -

Astrology, Mechanism and the Soul by Patrick J

Kepler’s Cosmological Synthesis: Astrology, Mechanism and the Soul by Patrick J. Boner History of Science and Medicine Library 39/Medieval and Early Modern Sci- ence 20. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2013. Pp. ISBN 978–90–04–24608–9. Cloth $138.00 xiv + 187 Reviewed by André Goddu Stonehill College [email protected] Johannes Kepler has always been something of a puzzle if not a scandal for historians of science. Even when historians acknowledged Renaissance, magical, mystical, Neoplatonic/Pythagorean influences, they dismissed or minimized them as due to youthful exuberance later corrected by rigorous empiricism and self-criticism.The pressure to see Kepler as a mathematical physicist and precursor to Newton’s synthesis remains seductive because it provides such a neat and relatively simple narrative. As a result, the image of Kepler as a mechanistic thinker who helped to demolish the Aristotelian world view has prevailed—and this despite persuasive characterization of Kepler as a transitional figure, the culmination of one tradition and the beginning of another by David Lindberg [1986] in referring to Kepler’s work on optics and by Bruce Stephenson [1987, 1–7] in discussing Kepler on physical astronomy. In this brief study, Patrick Boner once again challenges the image of Kepler as a reductivist, mechanistic thinker by summarizing and quoting passages of works and correspondence covering many of Kepler’s ideas, both early and late, that confirm how integral Kepler’s animistic beliefs were with his understanding of natural, physical processes. Among Boner’s targets, Anneliese Maier [1937], Eduard Dijksterhuis [1961], Reiner Hooykaas [1987], David Keller and E. -

Orbital Mechanics Joe Spier, K6WAO – AMSAT Director for Education ARRL 100Th Centennial Educational Forum 1 History

Orbital Mechanics Joe Spier, K6WAO – AMSAT Director for Education ARRL 100th Centennial Educational Forum 1 History Astrology » Pseudoscience based on several systems of divination based on the premise that there is a relationship between astronomical phenomena and events in the human world. » Many cultures have attached importance to astronomical events, and the Indians, Chinese, and Mayans developed elaborate systems for predicting terrestrial events from celestial observations. » In the West, astrology most often consists of a system of horoscopes purporting to explain aspects of a person's personality and predict future events in their life based on the positions of the sun, moon, and other celestial objects at the time of their birth. » The majority of professional astrologers rely on such systems. 2 History Astronomy » Astronomy is a natural science which is the study of celestial objects (such as stars, galaxies, planets, moons, and nebulae), the physics, chemistry, and evolution of such objects, and phenomena that originate outside the atmosphere of Earth, including supernovae explosions, gamma ray bursts, and cosmic microwave background radiation. » Astronomy is one of the oldest sciences. » Prehistoric cultures have left astronomical artifacts such as the Egyptian monuments and Nubian monuments, and early civilizations such as the Babylonians, Greeks, Chinese, Indians, Iranians and Maya performed methodical observations of the night sky. » The invention of the telescope was required before astronomy was able to develop into a modern science. » Historically, astronomy has included disciplines as diverse as astrometry, celestial navigation, observational astronomy and the making of calendars, but professional astronomy is nowadays often considered to be synonymous with astrophysics. -

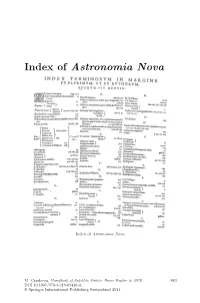

Index of Astronomia Nova

Index of Astronomia Nova Index of Astronomia Nova. M. Capderou, Handbook of Satellite Orbits: From Kepler to GPS, 883 DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-03416-4, © Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2014 Bibliography Books are classified in sections according to the main themes covered in this work, and arranged chronologically within each section. General Mechanics and Geodesy 1. H. Goldstein. Classical Mechanics, Addison-Wesley, Cambridge, Mass., 1956 2. L. Landau & E. Lifchitz. Mechanics (Course of Theoretical Physics),Vol.1, Mir, Moscow, 1966, Butterworth–Heinemann 3rd edn., 1976 3. W.M. Kaula. Theory of Satellite Geodesy, Blaisdell Publ., Waltham, Mass., 1966 4. J.-J. Levallois. G´eod´esie g´en´erale, Vols. 1, 2, 3, Eyrolles, Paris, 1969, 1970 5. J.-J. Levallois & J. Kovalevsky. G´eod´esie g´en´erale,Vol.4:G´eod´esie spatiale, Eyrolles, Paris, 1970 6. G. Bomford. Geodesy, 4th edn., Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1980 7. J.-C. Husson, A. Cazenave, J.-F. Minster (Eds.). Internal Geophysics and Space, CNES/Cepadues-Editions, Toulouse, 1985 8. V.I. Arnold. Mathematical Methods of Classical Mechanics, Graduate Texts in Mathematics (60), Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1989 9. W. Torge. Geodesy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1991 10. G. Seeber. Satellite Geodesy, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, 1993 11. E.W. Grafarend, F.W. Krumm, V.S. Schwarze (Eds.). Geodesy: The Challenge of the 3rd Millennium, Springer, Berlin, 2003 12. H. Stephani. Relativity: An Introduction to Special and General Relativity,Cam- bridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004 13. G. Schubert (Ed.). Treatise on Geodephysics,Vol.3:Geodesy, Elsevier, Oxford, 2007 14. D.D. McCarthy, P.K. -

Discovering Exoplanets Transiting Bright and Unusual Stars with K2

Discovering Exoplanets Transiting Bright and Unusual Stars with K2 ! ! PhD Thesis Proposal, Department of Astronomy, Harvard University ! ! Andrew Vanderburg! Advised by David! Latham ! ! ! April 18, 2015 After four years of surveying one field of view, the Kepler space telescope suffered a mechanical failure which ended its original planet-hunting mission, but has enabled a new mission (called K2) where Kepler surveys different fields across the sky. The K2 mission will survey 15 to 20 times more sky than the original Kepler mission, and in this wider field of view will be able to detect more planets orbiting rare objects. For my research exam, I developed a method to analyze K2 data that removes strong systematics from the light curves and enables planet detection. In my thesis, I propose to do the science enabled by my research exam work. I have already taken the work I completed for my research exam, upgraded and improved the method, and developed an automatic pipeline to search for transiting planets. I have searched K2 light curves for planets, produced a catalog of candidates, identified interesting planet candidates, and organized follow- up observations to confirm the discoveries. I propose to continue improving my software pipeline to detect even more planets, and produce a new catalog, and I propose to measure the mass of at least one of the resulting discoveries with the HARPS-N spectrograph. The resulting catalog will be a resource for astronomers studying these planets, and the investigations on interesting single objects will help us understand topics ranging from planet composition to the !evolution of planetary systems.