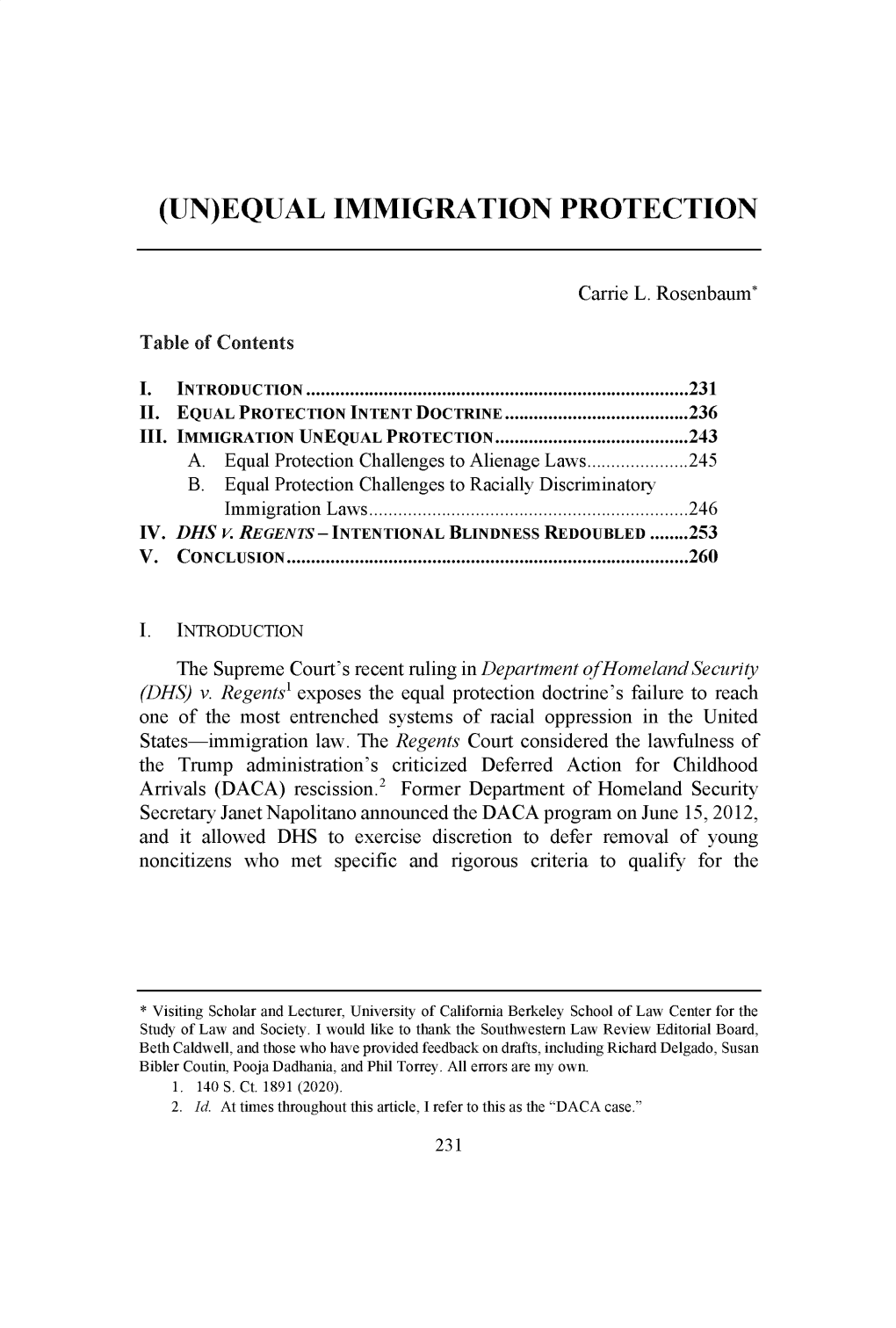

Equal Immigration Protection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Homeland Security

Homeland Security FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT TRAINING CENTERS OFFICE OF CHIEF COUNSEL ARTESIA LEGAL DIVISION ARTESIA, NM INDIAN LAW HANDBOOK 2016 Foreword October 2015 The Federal Law Enforcement Training Centers (FLETC) has a vital mission: to train those who protect our homeland. As a division of the Office of Chief Counsel, the Artesia Legal Division (ALG) is committed to delivering the highest quality legal training to law enforcement agencies and partner organizations in Indian Country and across the nation. In fulfilling this commitment, ALG Attorney-Advisors provide training on all areas of criminal law and procedure, including Constitutional law, authority and jurisdiction, search and seizure, use of force, self-incrimination, courtroom evidence, courtroom testimony, electronic law and evidence, criminal statutes, and civil liability. In addition, ALG provides instruction unique to Indian Country: Indian Country Criminal Jurisdiction, Conservation Law, and the Indian Civil Rights Act. My colleagues and I are pleased to present the first textbook from the FLETC that addresses the unique jurisdictional challenges of Indian Country: the Indian Law Handbook. It is our hope in the ALG that the Indian Law Handbook can serve all law enforcement students and law enforcement officers in Indian Country and can foster greater cooperation between the federal government, state, local, and tribal officers. An additional resource for federal, state, local and tribal law enforcement officers and agents is the LGD website: https://www.fletc.gov/legal-resources i The LGD website has a number of resources including articles, podcasts, links, federal circuit court and Supreme Court case digests, and The Federal Law Enforcement Informer. -

“Mexican Repatriation: New Estimates of Total and Excess Return in The

“Mexican Repatriation: New Estimates of Total and Excess Return in the 1930s” Paper for the Meetings of the Population Association of America Washington, DC 2011 Brian Gratton Faculty of History Arizona State University Emily Merchant ICPSR University of Michigan Draft: Please do not quote or cite without permission from the authors 1 Introduction In the wake of the economic collapse of the1930s, hundreds of thousands of Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans returned to Mexico. Their repatriation has become an infamous episode in Mexican-American history, since public campaigns arose in certain locales to prompt persons of Mexican origin to leave. Antagonism toward immigrants appeared in many countries as unemployment spread during the Great Depression, as witnessed in the violent expulsion of the Chinese from northwestern Mexico in 1931 and 1932.1 In the United States, restriction on European immigration had already been achieved through the 1920s quota laws, and outright bans on categories of Asian immigrants had been in place since the 19th century. The mass immigration of Mexicans in the 1920s—in large part a product of the success of restrictionist policy—had made Mexicans the second largest and newest immigrant group, and hostility toward them rose across that decade.2 Mexicans became a target for nativism as the economic collapse heightened competition for jobs and as welfare costs and taxes necessary to pay for them rose. Still, there were other immigrants, including those from Canada, who received substantially less criticism, and the repatriation campaigns against Mexicans stand out in several locales for their virulence and coercive nature. Repatriation was distinct from deportation, a federal process. -

Finalinvoluntary Deportations Lesson Plan

Identity, Immigration and Economics: The Involuntary Deportations of the 1930s (For use with Episode 2) Lesson Overview This particular lesson examines the involuntary deportations of Mexican immigrants and U.S. citizens of Mexican heritage during the 1930s. This displacement is only one of many legally sanctioned, forced relocations in our nation’s history. It also is an example of how a certain population may be scapegoated during times of economic downturn — and how there is an ongoing tie between immigration policies on the one hand, and economic trends on the other. Students analyze primary accounts and images from the 1930s, develop new vocabulary related to relocation, and demonstrate their understanding through creative writing. (Elements of this lesson were adapted from http://www.learnnc.org/lp/pages/4042.) Grade Level: 7 – 12 Time: 2 – 3 Hours (1 – 2 class periods) Materials • Internet access for research and viewing segment (Los Angeles Deportation) • Copies of student handout, Involuntary Deportation Images and Writing Prompts • Paper and pencils for note-taking and assignment writing/completion • Dictionary (print or online) Lesson Objectives The student will: 1. Define and discuss the difference between immigration, repatriation, deportation, resettlement and internment. 2. Identify the deportation of documented Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans during the Great Depression. 3. Present her/his learning to the class in the form of a vivid description of the individuals being deported and participate in a class debate on reasons for and against deportation. 4. Understand the importance and significance of the involuntary deportations of the 1930s. 5. Analyze the deportations in the context of immigration policies as connected to economic factors. -

Harvest Histories: a Social History of Mexican Farm Workers in Canada Since 1974”

“Harvest Histories: A Social History of Mexican Farm Workers in Canada since 1974” by Naomi Alisa Calnitsky B.A. (Hons.), M.A. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario ©2017 Naomi Calnitsky Abstract While concerns and debates about an increased presence of non-citizen guest workers in agriculture in Canada have only more recently begun to enter the public arena, this dissertation probes how migrant agricultural workers have occupied a longer and more complex place in Canadian history than most Canadians may approximate. It explores the historical precedents of seasonal farm labour in Canada through the lens of the interior or the personal on the one hand, through an oral history approach, and the external or the structural on the other, in dialogue with existing scholarship and through a critical assessment of the archive. Specifically, it considers the evolution of seasonal farm work in Manitoba and British Columbia, and traces the eventual rise of an “offshore” labour scheme as a dominant model for agriculture at a national scale. Taking 1974 as a point of departure for the study of circular farm labour migration between Mexico and Canada, the study revisits questions surrounding Canadian views of what constitutes the ideal or injurious migrant worker, to ask critical questions about how managed farm labour migration schemes evolved in Canadian history. In addition, the dissertation explores how Mexican farm workers’ migration to Canada since 1974 formed a part of a wider and extended world of Mexican migration, and seeks to record and celebrate Mexican contributions to modern Canadian agriculture in historical contexts involving diverse actors. -

Cappabianca Visual Essay

Meg Cappabianca Mexican Repatriation Eras of history can often be best demonstrated through images and documents from that time time period. These images can tell a story in a way that words can’t; this is definitely true of the Mexican repatriation, a movement that is often overlooked as it is one of the darkest and most shameful chapters in American history. Looking for a scapegoat for the Great Depression, local and state governments throughout America deported over one million people of Mexicans heritage--some of whom were American citizens. Entitled “repatriations” in order to avoid legal trouble for conducting mass deportations, these displacements served as a solution to the many white men who lost their jobs. There is little information on this shameful era, but the images and documents about the Mexican repatriations are very telling of the cruelty Mexicans and Mexican-Americans endured throughout these mass deportations. Following the stock market crash in 1929, America fell into a severe economic emergency that needed a solution. People were in dire need for jobs; as a result, white Americans were willing to take jobs that they previously wouldn’t have even considered. These were the jobs that required brute labor; previously, these jobs went to Mexican immigrants or Americans Source: NY Daily News, 1931 of Mexican descent because that’s all they could manage to get. In order to offer jobs to as many Americans as possible, the government needed to get rid of the people who currently held these lower positions. Many state and local governments turned to deportations in order to create job opportunities for white Americans. -

Bill Analysis

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES FINAL BILL ANALYSIS BILL #: HM 381 FINAL HOUSE FLOOR ACTION: SPONSOR(S): Hays Voice Vote Y’s --- N’s COMPANION SM 476 GOVERNOR’S ACTION: N/A BILLS: SUMMARY ANALYSIS HM 381 passed the House on April 21, 2014, as SM 476. The memorial serves as an application to Congress, pursuant to Article V of the Constitution of the United States, to call an Article V Convention of the states for the limited purpose of proposing three specific constitutional amendments. These include imposing fiscal restraints on the federal government, limiting the power and jurisdiction of the federal government, and limiting terms office for federal officials and members of Congress. The memorial does not have a fiscal impact. The memorial is not subject to the Governor’s veto power. This document does not reflect the intent or official position of the bill sponsor or House of Representatives. STORAGE NAME: h0281z1.LFAC DATE: May 12, 2014 I. SUBSTANTIVE INFORMATION A. EFFECT OF CHANGES: Introduction: Methods of Amending the U.S. Constitution Article V of the Constitution authorizes two methods for amending the Constitution: by Congress or by a constitutional convention. Congressional Amendments A constitutional amendment may be proposed by a two-thirds majority of both chambers in the form of a joint resolution. After Congress proposes an amendment, the Archivist of the United States is responsible for administering the ratification process under the provisions of 1 U.S.C. 106b. Since the President does not have a constitutional role in the amendment process, the joint resolution does not go to the White House for signature or approval. -

The Equal-Protection Challenge to Federal Indian Law

UNIVERSITY of PENNSYLVANIA JOURNAL of LAW & PUBLIC AFFAIRS Vol. 6 November 2020 No. 1 THE EQUAL-PROTECTION CHALLENGE TO FEDERAL INDIAN LAW Michael Doran* This article addresses a significant challenge to federal Indian law currently emerging in the federal courts. In 2013, the Supreme Court suggested that the Indian Child Welfare Act may be unconstitutional, and litigation on that question is now pending in the Fifth Circuit. The theory underlying the attack is that the statute distinguishes between Indians and non-Indians and thus uses the suspect classification of race, triggering strict scrutiny under the equal-protection component of the Due Process Clause. If the challenge to the Indian Child Welfare Act succeeds, the entirety of federal Indian law, which makes hundreds or even thousands of distinctions based on Indian descent, may be unconstitutional. This article defends the constitutionality of federal Indian law with a novel argument grounded in existing Supreme Court case law. Specifically, this article shows that the congressional plenary power over Indians and Indian tribes, which the Supreme Court has recognized for nearly a century and a half and which inevitably requires Congress to make classifications involving Indians and Indian tribes, compels the application of a rational-basis standard of review to federal Indian law. INTRODUCTION................................................................................................ 2 I. CONGRESSIONAL PLENARY POWER AND RATIONAL-BASIS REVIEW .......... 10 A. Congressional Plenary Power over Indians and Indian Tribes .......... 10 B. The Vulnerability of Morton v. Mancari .............................................. 19 * University of Virginia School of Law. For comments and criticisms, many thanks to Matthew L.M. Fletcher, Kim Forde-Mazrui, Lindsay Robertson, and George Rutherglen. -

3. the Powers and Tools Available to Congress for Conducting Investigative Oversight A

H H H H H H H H H H H 3. The Powers and Tools Available to Congress for Conducting Investigative Oversight A. Congress’s Power to Investigate 1. The Breadth of the Investigatory Power Congress possesses broad and encompassing powers to engage in oversight and conduct investigations reaching all sources of information necessary to carry out its legislative functions. In the absence of a countervailing constitutional privilege or a self-imposed restriction upon its authority, Congress and its committees have virtually plenary power to compel production of information needed to discharge their legislative functions. This applies whether the information is sought from executive agencies, private persons, or organizations. Within certain constraints, the information so obtained may be made public. These powers have been recognized in numerous Supreme Court cases, and the broad legislative authority to seek information and enforce demands was unequivocally established in two Supreme Court rulings arising out of the 1920s Teapot Dome scandal. In McGrain v. Daugherty,1 which considered a Senate investigation of the Justice Department, the Supreme Court described the power of inquiry, with accompanying process to enforce it, as “an essential and appropriate auxiliary to the legislative function.” The court explained: A legislative body cannot legislate wisely or effectively in the absence of information respecting the conditions which the legislation is intended to affect or change; and where the legislative body does not possess the requisite -

Federal Plenary Power": an Analysis of Case Law Affecting Tribal Sovereignty, 1886-1914

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Richmond University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book chapters and other publications Jepson School of Leadership Studies 1994 The U.S. Supreme Court's Explication of "Federal Plenary Power": An Analysis of Case Law Affecting Tribal Sovereignty, 1886-1914 David E. Wilkins University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/jepson-faculty-publications Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, and the Leadership Studies Commons Recommended Citation Wilkins, David E. “The U.S. Supreme Court’s Explication of ‘Federal Plenary Power’: An Analysis of Case Law Affecting Tribal Sovereignty, 1886-1914.” The American Indian Quarterly 18, no. 3 (June 1994), 349-368. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jepson School of Leadership Studies at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jepson School of Leadership Studies articles, book chapters and other publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Disclaimer: This is a machine generated PDF of selected content from our databases. This functionality is provided solely for your convenience and is in no way intended to replace original scanned PDF. Neither Cengage Learning nor its licensors make any representations or warranties with respect to the machine generated PDF. The PDF is automatically generated "AS IS" and "AS AVAILABLE" and are not retained in our systems. CENGAGE LEARNING AND ITS LICENSORS SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIM ANY AND ALL EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES, INCLUDING WITHOUT LIMITATION, ANY WARRANTIES FOR AVAILABILITY, ACCURACY, TIMELINESS, COMPLETENESS, NON-INFRINGEMENT, MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. -

Jurisdiction Stripping Circa 2020: What the Dialogue (Still) Has to Teach Us

MONAGHAN IN PRINTER FINAL (DO NOT DELETE) 9/16/2019 3:03 PM Duke Law Journal VOLUME 69 OCTOBER 2019 NUMBER 1 JURISDICTION STRIPPING CIRCA 2020: WHAT THE DIALOGUE (STILL) HAS TO TEACH US HENRY P. MONAGHAN† ABSTRACT Since its publication in 1953, Henry Hart’s famous article, The Power of Congress to Limit the Jurisdiction of Federal Courts: An Exercise in Dialectic, subsequently referred to as simply “The Dialogue,” has served as the leading scholarly treatment of congressional control over the federal courts. Now in its seventh decade, much has changed since Hart first wrote. This Article examines what lessons The Dialogue still holds for its readers circa 2020. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................2 A. 1953 and Beyond ......................................................................2 B. The Dialogue: A Preliminary Look ........................................5 I. The Essential Role of the Supreme Court ........................................10 A. Hart and the Court’s Essential Role....................................10 B. The Critical Responses and the Apparently Dominant View.........................................................................................13 C. Textual and Other Ambiguities ............................................16 D. The Supreme Court, Limited Government, and the Rule of Law...........................................................................................21 E. Purpose and Jurisdiction-Stripping ......................................27 -

Mexican Migrant Civil and Political Participation

Mexican Policy & Émigré Communities in the U.S. David R. Ayón Senior Researcher Center for the Study of Los Angeles Loyola Marymount University 1 LMU Drive Los Angeles, CA 90045 [email protected] Background Paper to be presented at the seminar “Mexican Migrant Social and Civic Participation in the United States.” To be held at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Washington D.C., November 4th and 5th, 2005. This seminar is sponsored by the Latin American and Latino Studies Department of the University of California, Santa Cruz and the Mexico Institute and Division of United States Studies of the Woodrow Wilson Center. With support from the Rockefeller, Inter- American, and Ford Foundations. 2 Mexican Policy & Émigré Communities in the U.S. David R. Ayón Abstract: Mexican policy toward emigration and its Diaspora in the U.S. has changed repeatedly since the Revolution. Initially, Mexico resisted emigration and sought to induce mass repatriation. This objective was fulfilled to a substantial degree during the Great Depression. From 1942-64, however, Mexico worked with the U.S. to channel temporary labor migration back north, and pressed to continue this arrangement. For a decade after it was cancelled, Mexico sought to restore this program. In 1975, however, Mexico renounced interest in any new guest worker arrangement and maintained this position publicly for the next 25 years. During this time, Mexico developed its first significant dialogue and relationship with U.S. citizens of Mexican descent. Since 1990, however, Mexican policy has shifted back to a focus on migrants, but now largely accepting their permanent settlement in the U.S. -

Mexican Communities in the Great Depression

ADVOCATES’ FORUM MEXICAN COMMUNITIES IN THE GREAT DEPRESSION Tadeo Weiner Davis Introduction It is tempting to think of history at the level of an event: A led to B, which led to C. But events are shaped by multiple forces. People amass themselves into groups, form social and economic institutions, and take the actions which comprise historical events. As social workers and street-level bureaucrats, we are uniquely positioned within these historical events. We do our jobs at the interface between the institutions charged with policy development and those tasked with policy implementation. As social workers, therefore, we are actors playing a role in implementing change and shaping history. We would do well, then, to study this history more carefully to better understand the development of current events and our role in them. Studying history can better equip us to disrupt systems of oppression before they permanently affect people’s lives. ocial workers serve some of the most marginalized and vulnerable individuals in society, and do so while straddling Sthe line between social work and social control. Immigrants are often recipients of social work services and targets of oppressive social control. The latter is true regardless of the political party in the White House—President Obama, for example, removed over three million immigrants from the United States during his presidency, more than the number removed under Presidents Bush and Clinton combined (Chishti, Pierce, & Bolter, 2017). With the exception of some advocacy groups, few protested Obama’s removals, mostly because the White House claimed to target individuals with serious criminal records.