50 Years of Double-Ended Ferry Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BORDENTOWN to ROEBLING VIA the RIVERLINE the Tracks for The

BORDENTOWN TO ROEBLING VIA THE RIVERLINE The tracks for the light rail train you are riding on were laid upon the right of way of the Camden & Amboy Railway Company, chartered in 1830 along with the Delaware & Raritan Canal Company (known as the “Joint Companies”) and laid in the1830s between Camden and Amboy. Both railroad and canal officially opened in 1834, but sections of the railroad were in service for freight in1833 with horse-drawn cars. Tied together and pulled by steam tugs, canalboats carrying coal from the Lehigh and Schuylkill Valleys would cross the river from Pennsylvania’s Delaware Canal. A cable ferry (1848-1912) and outlet locks at Lam- bertville and New Hope made the trip from the Lehigh Valley to Trenton much shorter, via the Feeder of the D & R. Schuylkill Valley coal continued to cross the river from Philadelphia and Bristol, entering the D&R at the Bor- dentown Lock (#1) at the mouth of Crosswicks Creek. What to look for Crosswicks Creek where it flows into the Delaware River Bluffs on the left on which Bordentown was built and the narrow strip of land under the bluffs where this train is traveling. Bordentown City is bordered on the south by Black’s Creek. Slips in the river shoreline on the lee side of Newbold Island where canalboats from Pennsylvania transferred their cargo (coal) to waiting trains or waited for entrance into Lock #1. Abandoned canalboats in the channel between Newbold Island and the shore, preserved because they are always wet. We have planned this trip for low tide so they can be seen. -

380 FT Towing Tank Justification

UNITED STATES NAVAL ACADEMY Annapolis, Maryland-21402 IN REPLY REFER TO: '7-2-69. From: Superintendent, U. S. Naval Academy To: Chief of Naval Personnel Subj: High Performance Towing Tank Ref: (a) NavPe~s ltr Pers-C322-jk of $ Octo~~r 196$ (b) COMNAVFACENGCOM memo of 1$ September 196$ (c) ENGR DEPT (USNA) INST 11000.2 of 30 June 196$ (d) ENGR DEPT (USNA) Rep'ort E-6$-5 "The Conceptual Design of a High Performance Towing Tank for the U. S ·i Na val Academy," 25 June 196$ . ( e ) "Just!ification for a Hydrodynamics Laboratory at the u. S. Naval Academy," 9 September 1968 I Encl: (1) Speci'fic Justification of a High Performance Towing Tank for the U. S. Naval Academy (2) Procurement of Equipment for a High Performance Towin;g Tank for th.e U. S. Naval Academy ( 3 ) Abst~act of Reference ( d) . 1. References (~) and (b) request further and specific justification fo,r construction of a high performance towing tank in the proposed new Engineering Department building. This justification is found in Enclosure (1). References (c) and (d) desdribe the proposed laboratory, and the required deve·lopment and design work. Enclosure ( 2) outlines possible means of reducing initial development . costs and procur,ing the required equipment. · Enclosure (3) abstracts refere,nce ( d) describing the tank and its equipm~nt. I . I . 2. Although cle~rly recognizing a critical need to save funds, it is my !conviction .that the proposed high perform ance towing tank is justified and must be included _in the proposed. new building. -

BC Ferry Review-FINAL-Dec17

Review of BC Ferry Corporation and Alternative Uses for the Fast Ferries Prepared by Fred R. Wright, FCA December 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A. Fast Ferries............................................................................................................. 1 B. BC Ferry Corporation .............................................................................................. 1 II. REQUEST FOR PUBLIC INPUT 3 III. ALTERNATIVE USES FOR THE FAST FERRIES A. Background ............................................................................................................ 5 B. BC Ferries’ Internal Review ..................................................................................... 5 C. PricewaterhouseCoopers Engagement .................................................................... 6 D. Public Input ............................................................................................................ 6 E. Kvaerner Masa Marine Proposal............................................................................... 6 F. Assessment and Recommendation .......................................................................... 7 IV. LESSONS LEARNED: A REVIEW OF THE GORDON AND MORFITT REPORTS ON THE FAST FERRIES A. Our Review ............................................................................................................. 8 B. Background ............................................................................................................ 8 C. The Gordon & Morfitt Reports................................................................................ -

SCHEDULE Chemainus

BC Ferries Schedules: Chemainus - Thetis Island - Penelakut Island Page 1 of 3 SCHEDULE Chemainus - Thetis Island - Penelakut Island (Chemainus - Preedy Harbour - Telegraph Harbour) Crossing Time: Chemainus to Thetis: 30 min/4 nautical miles Thetis to Penelakut: 15 min/1.7 nautical miles Penelakut to Chemainus: 30 min/4 nautical miles Distance: Varies - see above CHECK FOR SERVICE NOTICES Schedule in Effect: May 19, 2017 to March 31, 2018 On Dec 25 and Jan 1, service will commence with the 8:05 am sailing from Thetis Island with an irregular 8:20 am stop at Penelakut Island before proceeding to Chemainus. Chemainus to Thetis Island Leave Days Stops/Transfers Arrive 7:10 AM Daily except Dec 25 & Jan 1 1 stop Penelakut 8:00 AM 8:40 AM Daily except DC Thu non-stop 9:10 AM 9:50 AM Fri only 1 stop Penelakut 10:45 AM 10:10 AM Daily except Fri 1 stop Penelakut 11:10 AM 12:15 PM Daily except Fri 1 stop Penelakut 1:05 PM 12:45 PM Fri only non-stop 1:15 PM 1:50 PM Daily except Fri non-stop 2:15 PM 2:15 PM Fri only non-stop 2:45 PM 3:35 PM Daily except Fri 1 stop Penelakut 4:25 PM 3:50 PM Fri only 1 stop Penelakut 4:40 PM 5:10 PM Daily except Fri non-stop 5:40 PM 5:25 PM Fri only non-stop 5:55 PM 6:45 PM Daily except Fri non-stop 7:20 PM 7:00 PM Fri only non-stop 7:30 PM 8:25 PM Daily except Fri 1 stop Penelakut 9:15 PM 8:40 PM Fri only 1 stop Penelakut 9:30 PM 10:00 PM Daily except Fri 1 stop Penelakut 10:45 PM 10:15 PM Fri only 1 stop Penelakut 11:00 PM DC Dangerous Cargo sailings on certain Thursdays. -

BC Ferry Services Inc. Accessibility Advisory Committee Meeting Minutes

BC Ferry Services Inc. Accessibility Advisory Committee Meeting Minutes Meeting Details Date July 23, 2014 Time 1:00 pm – 4:00 pm Location: BC Ferries Head Office – Suite 500-1621 Blanshard Street Attendance Public Interest Representatives Pat Danforth, Board Member, BC Coalition of People with Disabilities Susan Gallagher, Alliance for Equality of Blind Canadians Hugh Mitchell, Canadian Hard of Hearing Association Scott Heron, Co-Chair, Spinal Cord Injury BC Jane Sheaff, Seniors Serving Seniors Ernie Stignant, Disability Resource Centre/MSI Mary K. Kennedy, CNIB Marnie Essery, Inter-municipal Advisory Committee on Disability Issues Les Chan, Disability Resource Centre Barbara Schuster, CNIB BC Ferries Representatives Karen Tindall, Director of Customer Care, Customer Care Department Garnet Renning, Customer Service & Sales Representative Stephen Nussbaum, Regional Manager, Swartz Bay David Carroll, Director, Terminal Construction, Engineering Darin Guenette, Manager, Public Affairs Bruce Paterson, Fleet Technical Director, Engineering Sheila O’Neill, Catering Superintendent, Central Coast Captain Chris Frappell, Marine Superintendent, South and Central Coast Guests Jeffrey Li, Project Manager Joanne Doyle, Manager, Master Planning Elisabeth Broadley, Customer Relations Advisor, Customer Care Regrets Valerie Thoem, Independent Steve Shardlow, Training Manager, Terminals Jeff Davidson, Director, Retail Services, Food and Retail Operations 1 | P a g e Introductions Co-Chairs Scott Heron and Karen Tindall welcomed the members of the committee Review of Minutes – February 4, 2014 Karen Tindall reported on Action Items from last meeting Note: July 23 was Ernie Stignant’s last meeting – Les Chan will be representing the Disability Resource Centre Standing Items Loading Practices Stephen Nussbaum went through six months’ worth of customer comments looking for trends in comments from persons with disabilities. -

Made-In-Bc Ferries the Economic Benefits of Local Ship Procurement

MADE-IN-BC FERRIES THE ECONOMIC BENEFITS OF LOCAL SHIP PROCUREMENT by Blair Redlin and David Fairey March 2014 MADE-IN-BC FERRIES: THE ECONOMIC BENEFITS OF LOCAL SHIP PROCUREMENT 1 PART 1 Introduction Institutional procurement is a powerful, and often underutilized, economic development strategy that can positively impact “value added” economic sectors. How and where procurement dollars are spent can have important economic effects.1 Beyond the service sector, British Columbia’s economy relies significantly on natural resources, with 7.5 per cent of provincial GDP and 3.1 per cent of provincial employment in those sectors. BC’s value added sector – primary processing beyond hewing wood and drawing water – represents an additional 4.1 per cent of GDP and 3.6 per cent of employment. While 2012 manufacturing GDP was 7.2 per cent of total GDP and manufacturing employment was 7.7 per cent of total employment, BC Statistics tables show overall manufacturing trending downward 12 per cent since 2007.2 In July 2013, BC Ferries announced it will put three new intermediate class ferries into service by 2016/2017. The corporation is seeking a fixed price design/ build contract for the three new ferries and hopes to use liquefied natural gas to fuel the new vessels.3 BC Ferries has an opportunity to contribute to BC’s economic development through its procurement choices. As an institution providing a public service, with public dollars, it can be argued that BC Ferries has an additional responsibil- ity to consider the economic development impact of its procurement spending. Analysis by Stokes Economic Consulting, using the Centre for Spatial Eco- nomics provincial economic model, shows the economic advantage of building these ferries in BC: for every 100 jobs created in a BC shipyard or repair industry, 1 Tony Pringle and Robert Duffy, Buying Local: Purchasing Tools for Forward Thinking Institutions, Columbia Institute, 2013. -

British Columbia Ferry Services Inc. May 28, 2021

British Columbia Ferry Services Inc. Application to the British Columbia Ferries Commissioner Pursuant to Section 55 (2) of the Coastal Ferry Act For the Island Class Electrification Program May 28, 2021 Note: In this copy of the Application, information of a confidential and commercially-sensitive nature has been redacted. Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................... 2 Section 1 – Introduction .............................................................................................. 3 1.1 Application Overview ...................................................................................... 3 1.2 Organization of Application ............................................................................. 5 Section 2 – Current Environment ................................................................................. 6 2.1 Overview ...................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Integrating Clean Technologies into BC Ferries’ Operations ................................. 7 2.3 Island Class Vessels ....................................................................................... 8 Section 3 – Program Overview ..................................................................................... 9 3.1 Program History and Rationale ........................................................................ 9 3.2 Program Summary ...................................................................................... -

Assessment of BC Ferries' PT5 Submission

www.pwc.com/ca Assessment of BC Ferries’ PT5 Submission British Columbia Ferry Commission March 2019 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 Introduction 5 Purpose and Scope of the Assessment 5 Organization of the Report 6 Notice to Reader 6 Assessment of BC Ferries’ PT5 Submission and Supporting Documentation 7 Historical Traffic Trends 8 Traffic Forecasts for the Balance of PT4 8 Assessment of Financial Forecasts for the Balance of PT4 1 0 Reasonableness of PT4 Expense Growth 1 2 Impact of Fare Initiatives in PT4 1 4 PT4 Capital Expenditures 15 Debt Covenants 1 6 Achievement of Targets in the Capital Plan and Efficiency Plan in PT4 16 Alternative Service Providers 1 7 Price Cap Compliance 1 7 Drop Trailer Compliance 1 8 Conclusions 1 8 Assessment of Fuel Management Plan Outcomes in Performance Term Four 19 Fuel Consumption 19 Fuel Management 2 1 Fuel Deferral Program 2 1 Conclusions 2 2 Assessment of BC Ferries’ 2019-2030 Capital Plan Submission 2 3 Introduction 2 3 Capital Plan Summary 2 3 Approach to the Capital Cost Estimates 2 4 Commentary 2 5 Conclusions 33 Assessment of Strategies for Enhanced Efficiency in PT5 and Beyond 34 Introduction 34 Summary of the Strategies for Enhanced Efficiency 34 Improving On-time Performance 35 Revenue Opportunities 36 Conclusions 37 Assessment of BC Ferries’ Traffic Demand Forecasting 38 Overview 38 Changes in Traffic Forecasting Between PT4 and PT5 39 PT5 Forecast Results and Price Elasticities 41 Impact of the FFDEI & Seniors Program on Traffic 42 Conclusions and Recommendations 43 BC Ferry Commission’s -

BC Page1 BC Ferries Departure Bay Passenger Facilities

BC Ferries Departure Bay Passenger Facilities | Nanaimo, BC Clive Grout Architect Inc. This BC Ferries’ project consists of a 28,000 sq ft building which includes ticketing and arrivals hall, baggage pick up and drop off, departures/arrivals corridor, retail shops, food court, washrooms, waiting lounge and escalator connection to the ship’s load/unload gangway. The project also includes an exterior courtyard and children’s area. Retail and food facilities are accessible to both foot and vehicle passengers. Wood was an excellent choice for ceiling and exterior fascia material as the architects desired to introduce a signature material to the landside facilities symbolic of the land and mountains of coastal B.C. as a contrast to the experience of the sea on the ships. In creating an image for the new passenger facilities, the architects selected the warmth and comfort of wood expressed on the ceiling, leaving the floors for utilitarian finishes and the walls for full glass to integrate visually with the spectacular setting on the edge of the water. The dramatic shape of the building and its roof, dictated by the site planning constraints, is enhanced by the prominence of the wood panels. The architects took two key steps to ensure the long-term durability of the fir veneer in coastal B.C.’s sea air and rain environment. The fascias are designed to slope sharply from the edge, keeping them out of the line of the direct rain. The entire assembly was initially rigorously and successfully tested by Forintek Canada for boiling water emersion, dry peel and room temperature delamination, giving the client and architect confidence in the application. -

Review of Coastal Ferry Services

CONNECTING COASTAL COMMUNITIES Review of Coastal Ferry Services Blair Redlin | Special Advisor June 30, 2018 ! !! PAGE | 1 ! June 30, 2018 Honourable Claire Trevena Minister of Transportation and Infrastructure Parliament Buildings Victoria BC V8W 9E2 Dear Minister Trevena: I am pleased to present the final report of the 2018 Coastal Ferry Services Review. The report considers the matters set out in the Terms of Reference released December 15, 2017, and provides a number of recommendations. I hope the report is of assistance as the provincial government considers the future of the vital coastal ferry system. Sincerely, Blair Redlin Special Advisor ! TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................................................ 3! 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................................................................... 9! 1.1| TERMS OF REFERENCE ...................................................................................................................................................... 10! 1.2| APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................ 12! 2 BACKGROUND .................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Course Objectives Chapter 2 2. Hull Form and Geometry

COURSE OBJECTIVES CHAPTER 2 2. HULL FORM AND GEOMETRY 1. Be familiar with ship classifications 2. Explain the difference between aerostatic, hydrostatic, and hydrodynamic support 3. Be familiar with the following types of marine vehicles: displacement ships, catamarans, planing vessels, hydrofoil, hovercraft, SWATH, and submarines 4. Learn Archimedes’ Principle in qualitative and mathematical form 5. Calculate problems using Archimedes’ Principle 6. Read, interpret, and relate the Body Plan, Half-Breadth Plan, and Sheer Plan and identify the lines for each plan 7. Relate the information in a ship's lines plan to a Table of Offsets 8. Be familiar with the following hull form terminology: a. After Perpendicular (AP), Forward Perpendiculars (FP), and midships, b. Length Between Perpendiculars (LPP or LBP) and Length Overall (LOA) c. Keel (K), Depth (D), Draft (T), Mean Draft (Tm), Freeboard and Beam (B) d. Flare, Tumble home and Camber e. Centerline, Baseline and Offset 9. Define and compare the relationship between “centroid” and “center of mass” 10. State the significance and physical location of the center of buoyancy (B) and center of flotation (F); locate these points using LCB, VCB, TCB, TCF, and LCF st 11. Use Simpson’s 1 Rule to calculate the following (given a Table of Offsets): a. Waterplane Area (Awp or WPA) b. Sectional Area (Asect) c. Submerged Volume (∇S) d. Longitudinal Center of Flotation (LCF) 12. Read and use a ship's Curves of Form to find hydrostatic properties and be knowledgeable about each of the properties on the Curves of Form 13. Calculate trim given Taft and Tfwd and understand its physical meaning i 2.1 Introduction to Ships and Naval Engineering Ships are the single most expensive product a nation produces for defense, commerce, research, or nearly any other function. -

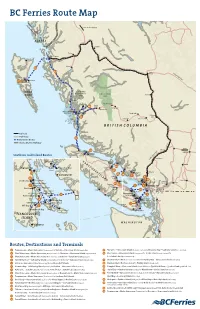

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver