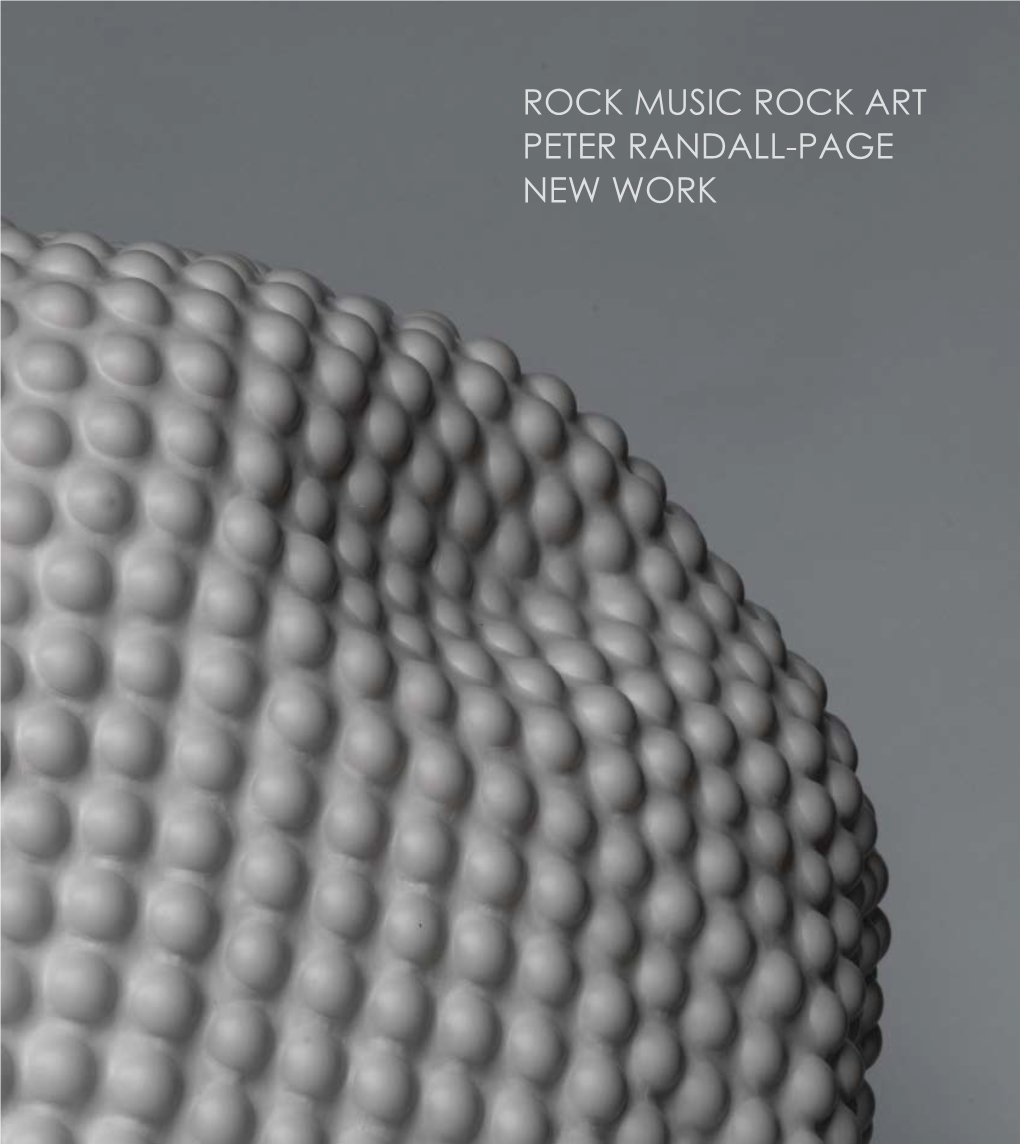

Rock Music Rock Art Peter Randall-Page New Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Booklet

161Booklet 12/3/09 09:38 Page 1 ALSO AVAILABLE on signumclassics Peter Warlock: Some Little Joy I Love All Beauteous Things: Choral and Organ Music SIGDVD002 by Herbert Howells The Choir of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin A film drama about a man who, by his SIGCD151 death at thirty six, had composed some of the most perfect gems of English Herbert Howells has an assured place in the annals of English songwriting and elevated hedonism to an church music, however his popular reputation is founded largely on art form. the frequent performance of a small body of core works. This recording redresses the balance in exploring some much less well- known pieces, with impassioned performances from the Choir of Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin. Available through most record stores and at www.signumrecords.com For more information call +44 (0) 20 8997 4000 161Booklet 12/3/09 09:38 Page 3 THE frostbound wood 16. When the Dew is Falling Herbert Howells [3.36] 17. Full Moon Herbert Howells [2.59] 1. My Little Sweet Darling Peter Warlock [1.59] Noble Numbers Betty Roe 18. To His Saviour, a Child; a Present, by a Child [1.35] 2. Take, O Take Those Lips Away Peter Warlock [1.35] 19. To God; An anthem sung before the King in 3. And Wilt Thou Leave Me Thus? Peter Warlock [1.59] the chapel at Whitehall [2.43] 4. Sleep Peter Warlock [2.10] 20. To God [0.53] 21. To His Angrie God [1.41] 5. The Droll Lover Peter Warlock [0.57] 22. -

WEST Sidemartin Drive

Approximate boundaries: N-W. Vliet St; S-W. Martin Dr-W. Highland Blvd; E-N. 35th St; W-Wisconsin Hwy 175 WEST SIDEMartin Drive NEIGHBORHOOD DESCRIPTION Comprising little more than a square half mile in size, Martin Drive is tucked away between the Olmstead-designed Washington Park to the north and Historic Miller Valley to the south. It’s chiefly one-way streets are tree-lined, and many of the homes are duplexes. Both Highland Boulevard and Martin Drive are winding streets. Due to its small size, the neighborhood has only one commercial corridor and this is on Vliet Street. HISTORY Much of the small Martin Drive neighborhood was developed in the 1920s. Unlike the elite areas on nearby Highland Boulevard, this became a working class neighborhood. Workers living in Martin Drive had several large employers nearby, including Harley Davidson, Miller Brewery, and the Transport Company. Other industrial employers were just a few blocks away in the Menomonee Valley. Bordered by the sprawling Washington Park to the north, residents had quick access to picnic areas, programs, and the county’s zoo. Many could stop to observe all the outdoor animals on their way to work or school. Much changed during the era of freeway building, when I-41 cut into Washington Park and the zoo was relocated to the far west side of Milwaukee. Many homes were also lost on 47th Street between Vliet Street and Juneau Avenue. The neighborhood became even smaller, but did not lose its cohesiveness. Early populations The early population of Martin Drive was almost totally German. -

Jantar Mantar Strike Seeks a Sustainable Earth

STUDENT PAPER OF TIMES SCHOOL OF MEDIA GREATER NOiDA | MONDAY, OCTOBER 14, 2019 | VOL 3 , ISSUE 8 | PAGES 8 THE TIMESOF BENNETT Exploring a slice of Tibet in Delhi Trophy from the hunt Hip-hop: culture over trends The ISAC Walk 1.0 : Glimpses of Geeta Bisht, BU’s front desk executive, on Rapper’s take on today’s the photowalk to Majnu-ka-tilla winning the Super Model Hunt 2019 hip-hop industry | Page 5 | Page 4 | Page 6 BU hosts 1st inter-college sports fest, Expedite 2019 Silent walks to By ASHIMA CHOUDHARY were soul-stirring. As the the yum eateries. Even Zardicate came together was one to remember. took trophies, cash mon- Bennett University con- audience and athletes Mrs. Pratima was thrilled to mellow down the stress The crowd lit up the night ey and hampers home! fight harassment ducted its first-ever came together, the event to see the level of enthu- from the tournaments. with grooving students The stir caused by sports fest from 27th to electrified the atmosphere. siasm shown by students. The first night ended with and radium accessories. the fest was palpable as 29th of September. It Food stalls, to source In her words, “I expect- a bonfire, relaxing every- The DJ night lasted well Yashraj Saxena, former welcomed 400 students everyone’s energy, were ed it to be chaotic, but one, but it was the 28th, into the hours. Everyone head of the committee, from 16 universities from voiced his words, “We’ve the Delhi NCR region, been trying to host this Jaipur, Gwalior and a for the past two years. -

Fishing the Red River of the North

FISHING THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH The Red River boasts more than 70 species of fish. Channel catfish in the Red River can attain weights of more than 30 pounds, walleye as big as 13 pounds, and northern pike can grow as long as 45 inches. Includes access maps, fishing tips, local tourism contacts and more. TABLE OF CONTENTS YOUR GUIDE TO FISHING THE RED RIVER OF THE NORTH 3 FISHERIES MANAGEMENT 4 RIVER STEWARDSHIP 4 FISH OF THE RED RIVER 5 PUBLIC ACCESS MAP 6 PUBLIC ACCESS CHART 7 AREA MAPS 8 FISHING THE RED 9 TIP AND RAP 9 EATING FISH FROM THE RED RIVER 11 CATCH-AND-RELEASE 11 FISH RECIPES 11 LOCAL TOURISM CONTACTS 12 BE AWARE OF THE DANGERS OF DAMS 12 ©2017, State of Minnesota, Department of Natural Resources FAW-471-17 The Minnesota DNR prohibits discrimination in its programs and services based on race, color, creed, religion, national origin, sex, public assistance status, age, sexual orientation or disability. Persons with disabilities may request reasonable modifications to access or participate in DNR programs and services by contacting the DNR ADA Title II Coordinator at [email protected] or 651-259-5488. Discrimination inquiries should be sent to Minnesota DNR, 500 Lafayette Road, St. Paul, MN 55155-4049; or Office of Civil Rights, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C. Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20240. This brochure was produced by the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Division of Fish and Wildlife with technical assistance provided by the North Dakota Department of Game and Fish. -

Henry Moore Grants Awarded 2016-17

Grants awarded 2016-17 Funding given by Henry Moore Grants 1 April 2016 – 31 March 2017 New projects Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, Exhibition: The Mythic Method: Classicism in British Art 1920-1950, 22 October 2016-19 February 2017 - £5,000 Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, Exhibition: Heather Phillipson and Ruth Ewan's participation in 32nd Bienal de São Paulo - Live Uncertainty, 7 September-11 December 2016 - £10,000 Serpentine Gallery, London, Exhibition: Helen Marten: Drunk Brown House, 29 September-20 November 2016 - £7,000 Auto Italia South East, London, Exhibition: Feral Kin, 2 March-9 April 2017- £2,000 Art House Foundation, London, Exhibition: Alison Wilding Arena Redux, 10 June-9 July 2016 - £5,000 Parasol Unit Foundation for Contemporary Art, London, Exhibition: Robert Therrien: Works 1975- 1995, 2 October-11 December 2016 - £5,000 South London Gallery, Exhibition: Roman Ondak: The Source of Art is in the Life of a People, 29 September 2016-6 January 2017 - £7,000 York Art Gallery (York Museums Trust), Exhibition: Flesh, 23 September 2016-19 March 2017 - £6,000 Foreground, Frome, Commissions: Primary Capital Programme: Phase 1, 8 September 2016-31 January 2017 - £6,000 Barbican Centre Trust, London, Exhibition at The Curve: Bedwyr Williams: The Gulch, 29 September 2016-8 January 2017- £10,000 Glasgow Sculpture Studios, Exhibition: Zofia Kulik: Instead of Sculpture, 1 October-3 December 2016 - £5,000 Tramway, Glasgow: Exhibition/Commission: Claire Barclay: Yield Point, 10 February-9 April 2017 - £3,000 Nasher Sculpture Center, -

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan A Comprehensive Listing of the Vessels Built from Schooners to Steamers from 1810 to the Present Written and Compiled by: Matthew J. Weisman and Paula Shorf National Museum of the Great Lakes 1701 Front Street, Toledo, Ohio 43605 Welcome, The Great Lakes are not only the most important natural resource in the world, they represent thousands of years of history. The lakes have dramatically impacted the social, economic and political history of the North American continent. The National Museum of the Great Lakes tells the incredible story of our Great Lakes through over 300 genuine artifacts, a number of powerful audiovisual displays and 40 hands-on interactive exhibits including the Col. James M. Schoonmaker Museum Ship. The tales told here span hundreds of years, from the fur traders in the 1600s to the Underground Railroad operators in the 1800s, the rum runners in the 1900s, to the sailors on the thousand-footers sailing today. The theme of the Great Lakes as a Powerful Force runs through all of these stories and will create a lifelong interest in all who visit from 5 – 95 years old. Toledo and the surrounding area are full of early American History and great places to visit. The Battle of Fallen Timbers, the War of 1812, Fort Meigs and the early shipbuilding cities of Perrysburg and Maumee promise to please those who have an interest in local history. A visit to the world-class Toledo Art Museum, the fine dining along the river, with brew pubs and the world famous Tony Packo’s restaurant, will make for a great visit. -

Days & Hours for Social Distance Walking Visitor Guidelines Lynden

53 22 D 4 21 8 48 9 38 NORTH 41 3 C 33 34 E 32 46 47 24 45 26 28 14 52 37 12 25 11 19 7 36 20 10 35 2 PARKING 40 39 50 6 5 51 15 17 27 1 44 13 30 18 G 29 16 43 23 PARKING F GARDEN 31 EXIT ENTRANCE BROWN DEER ROAD Lynden Sculpture Garden Visitor Guidelines NO CLIMBING ON SCULPTURE 2145 W. Brown Deer Rd. Do not climb on the sculptures. They are works of art, just as you would find in an indoor art Milwaukee, WI 53217 museum, and are subject to the same issues of deterioration – and they endure the vagaries of our harsh climate. Many of the works have already spent nearly half a century outdoors 414-446-8794 and are quite fragile. Please be gentle with our art. LAKES & POND There is no wading, swimming or fishing allowed in the lakes or pond. Please do not throw For virtual tours of the anything into these bodies of water. VEGETATION & WILDLIFE sculpture collection and Please do not pick our flowers, fruits, or grasses, or climb the trees. We want every visitor to be able to enjoy the same views you have experienced. Protect our wildlife: do not feed, temporary installations, chase or touch fish, ducks, geese, frogs, turtles or other wildlife. visit: lynden.tours WEATHER All visitors must come inside immediately if there is any sign of lightning. PETS Pets are not allowed in the Lynden Sculpture Garden except on designated dog days. -

Top 1Oo Family Fishing & Boating Spots

2016 TOP 1OO FAMILY FISHING & BOATING SPOTS IN AMERICA Gather the kids, pack the bait and tackle, hit the road, and drop your line. These are this year’s top destinations for family fishing, as decided by nearly 650,000 votes cast by anglers across the country. West 25 Brannan Island State Park / Sacramento River 700 miles of channels and sloughs wind Clear Lake State Park / Clear Lake through a chain of islands and marshes. The record largemouth bass caught in Clear Lake is 17.52 pounds. 1 14 Yosemite National Park 19 2 16 The mountains in Yosemite are still 7 5 13 12 growing 1 foot every 1,000 years. 15 Dockweiler State Beach / Santa Monica Bay Surf fishers regularly catch halibut, corbina, 3 croaker and surfperch from the beach. 23 10 24 18 21 9 Koke'e State Park Pu’u Lua Reservoir is stocked with more than 30,000 rainbow trout annually. 17 4 11 20 8 22 6 6 Wailoa River State Park / Hilo Bay 10 Lake Havasu State Park / Lake Havasu 14 Lake Shasta / Bridge Bay 18 Lake Pleasant Regional Park / Lake Pleasant 22 Kepler-Bradley Lake State Recreation Area / Kepler + Bradley Lakes 7 Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National 11 Birch Lake State Park / Birch Lake 15 Chatfield State Park / Chatfield Lake 19 Doran Regional Park / Bodega Bay 23 Echo Park / Echo Park Lake Wildlife Refuge / San Francisco Bay 8 Malaekahana State Recreational Area / 12 Aurora Reservoir Park / Aurora Reservoir 16 Boyd Lake State Park / Boyd Lake 20 Waimea State Recreational Pier / 24 Deadhorse Ranch State Park Pacific Ocean Waimea Bay 9 Big Lake Recreation Area/ Big Lake 13 Rocky Mountain National Park 17 Borough Park/ Chena Lake 21 Fool Hollow Lake Recreation Area / 25 Olympic National Park Fool Hollow Lake Midwest Fort Custer State Park / Eagle Lake The U.S. -

Creative Flow

Using marine debris, painted silk, Creative Flow and paper, artist Pam Longobardi, Linda Gass, and Lauren Rosenthal Three Activist Artists advocate for greater consciousness by Sally Hansell of our fragile water systems. owerful new work by three activist artists addresses one of the nation’s most critical issues—the steady degradation of our precious water supply. Pam Lon- gobardi uses plastic trash collected on beaches to Pmake provocative art that points to the devastating dangers of plastic in our environment. Linda Gass creates vibrant paint- ed-silk quilt works depicting specific ecological hazards in San Francisco Bay. Lauren Rosenthal turns watershed data into cut- paper sculptures to demonstrate the interconnectedness of riv- ers and earthly organisms. Through their chosen media, these diverse artists advocate for a heightened global ecological con- sciousness. In 2006, Pam Longobardi launched an ongoing project called Drifters after encountering mounds of consumer waste on the beach at South Point, the southernmost tip of the Hawaiian Islands. The project includes photography, sculp- ture, public art, and installations made from the debris that washes up on shores around the world. The Atlanta artist creates “driftwebs” from abandoned drift nets, the miles-long fishing nets that wreak havoc on sea life, killing fish, mammals, turtles, and birds. She cuts and ties pieces of the nets to make installations resembling spider webs. Her intent is not only to draw attention to the dan- gerous plastic nets, but more importantly, to use their woven colorful forms as a dual metaphor for the predatory, destruc- tive behavior of humankind and the interconnectedness of the web of life. -

North Dakota Public Fishing Waters Statewide List by County Name

North Dakota Public Fishing Waters Data as of: September 24, 2021 The following lists all public fishing waters alphabetically by county name. Each listing includes travel directions , current status of the fishery for the upcoming season, and fishing piers (listed if present). Lakes without a boat ramp are listed as ‘no ramp’. Large systems have multiple access sites listed separately, with camping and other facilities noted along with the entity responsible for managing the facility. Click on the Lake Name to view a contour map or aerial photo showing the access point for the lake. The Current Lake Elevation is listed if known. All elevation data is in Datum NAVD88. Stocking will list fish stocking for the last 10 years. Survey Report provides a summary of the most recent data (within the last 10 years) collected by fisheries biologists during their standard sampling. Length Table provides a table of the sizes of fish measured by fisheries biologists during their most recent standard sampling. Length Chart provides a graph of the sizes of Statewide List by County Name Adams County Mirror Lake Stocking Survey Report Length Table Length Chart South side of Hettinger. Bullheads up to a 1/2 pound abundant. Good number of channel catfish up to 5 pounds (stocked annually). Some northern pike up to 3 pounds, walleye up to 1 pound, bluegill up to 1/2 pound and mostly small yellow perch. 6,600 adult yellow perch stocked in 2021. (Fishing pier). North Lemmon 2,484.0 msl Stocking Survey Report Length Table Length Chart 5 miles north of Lemmon, South Dakota. -

Hillside NEIGHBORHOOD DESCRIPTION the Hillside Neighborhood Is a Residential Island Surrounded by Industry and Freeways

Approximate boundaries: N-N. Halyard St; S-W. Fond Du Lac Ave; E-N. 6th St; W-Hwy 43 NORTH SIDEHillside NEIGHBORHOOD DESCRIPTION The Hillside neighborhood is a residential island surrounded by industry and freeways. The main housing styles in Hillside are the multi-story apartment complexes and one- story homes around the parks. Interspersed are a few old industrial buildings. There are two parks in the Hillside neighborhood--James W. Beckum Park, which has an area for little league baseball, and Carver Park, a 23-acre space with playground equipment. See photos below. HISTORY The area that is today’s Hillside neighborhood is located in the center of what was once known as the city’s Bronzeville community (with borders within Juneau and North Avenues, and old 3rd and 17th Streets— the widest area given by local historians). And before there was Bronzeville, there were other communities in today’s Hillside area. Early populations The original area comprising Hillside was developed after 1850. The early population was mostly German and they lived within walking distance of jobs at tanneries, the Schlitz Brewery, shoe factories, and mills. The Hillside neighborhood specifically attracted a number of German elite. According to John Gurda in Milwaukee, City of Neighborhoods (p. 188): So many Uihleins (owners of the Schlitz Brewery) lived on or near Galena Street that the area was known as “Uihlein Hill,” conveniently overlooking the family’s Third Street brewing complex. One of their mansions, which stayed in the family until the 1940s, stood just north of what is now the Hillside Terrace Family Resource Center. -

Art Works Grants

National Endowment for the Arts — December 2014 Grant Announcement Art Works grants Discipline/Field Listings Project details are as of November 24, 2014. For the most up to date project information, please use the NEA's online grant search system. Art Works grants supports the creation of art that meets the highest standards of excellence, public engagement with diverse and excellent art, lifelong learning in the arts, and the strengthening of communities through the arts. Click the discipline/field below to jump to that area of the document. Artist Communities Arts Education Dance Folk & Traditional Arts Literature Local Arts Agencies Media Arts Museums Music Opera Presenting & Multidisciplinary Works Theater & Musical Theater Visual Arts Some details of the projects listed are subject to change, contingent upon prior Arts Endowment approval. Page 1 of 168 Artist Communities Number of Grants: 35 Total Dollar Amount: $645,000 18th Street Arts Complex (aka 18th Street Arts Center) $10,000 Santa Monica, CA To support artist residencies and related activities. Artists residing at the main gallery will be given 24-hour access to the space and a stipend. Structured as both a residency and an exhibition, the works created will be on view to the public alongside narratives about the artists' creative process. Alliance of Artists Communities $40,000 Providence, RI To support research, convenings, and trainings about the field of artist communities. Priority research areas will include social change residencies, international exchanges, and the intersections of art and science. Cohort groups (teams addressing similar concerns co-chaired by at least two residency directors) will focus on best practices and develop content for trainings and workshops.